Raphael's Ansidei Altarpiece in the National Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Exegesis and Eschatology in the Sistine Chapel

TYPOLOGY AT ITS LIMITS: VISUAL EXEGESIS AND ESCHATOLOGY IN THE SISTINE CHAPEL Giovanni Careri Typology is a central device in the Sistine chapel frescoes of the fifteenth century where it works, in a quite canonical way, as a model of histori- cal temporality with strong institutional effects. In the frescoes by Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta representing various episodes from the life of Moses, including his death, every gesture and action of Moses is an announcement – a figura – of Jesus Christ’s institutional accomplish- ments represented on the opposite wall [Fig. 1]. Some of these devices operate on a figural level rather than in mere iconographical terms; the death of Moses, for instance, is a Pathosformel: the leader of the Israelites dies in the pose of the dead body of Christ, while his attendants adum- brate the Lamentation of Christ. Here, the attitude of the defunct Moses is ‘intensified’ by the return of the pathetic formula embodied by Christ’s Fig. 1. Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta, Last Acts and Death of Moses (1480–1482). Oil on panel, 21.6 × 48 cm. Vatican City, Sistine Chapel. 74 giovanni careri corpse, that is, by the paradoxical return of the figure who is prefigured by Moses himself. As Leopold Ettlinger extensively showed, the main ideological purpose of the Quattrocento cycle is to support and incontrovertibly to adduce papal primacy.1 Nevertheless, if we look at these frescoes from an anthro- pological point of view, we are compelled to observe the extent to which they appropriate the history of the ‘Other’ – in this case the history of the Jews – entirely transforming it into a sort of prophetical premise for Christian history itself. -

The Domed Temple in Renaissance Italy and in Early Printed Sources

CHAPTER EIGHT THE DOMED TEMPLE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY AND IN EARLY PRINTED SOURCES During the Italian Renaissance the motif of the circular or octagonal Temple of Solomon took on a life of its own, for it became linked to the idea of a centralized church plan. Such a circular plan with its uniformity and har- mony came to connote the justice of God. Architects of the period ranked round and domical temples above all others, often spurred on, additionally, by their admiration for classical Roman architecture such as the Pantheon.1 In this climate, evoking Solomon’s Temple as a circular building was per- fectly natural, even though it contradicted the biblical text and the rectilin- ear measurements supposedly handed down by God.2 One of the first Renaissance paintings to include a circular Temple is Perugino’s “Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter” in the Sistine Chapel, dating from 1481. (fig. 8.1) Perugino executed the painting under the patronage of Sixtus IV, the pope responsible for the remodeling of the old Capella Magna into the new Sistine Chapel. The architecture and the mural paintings were planned simultaneously in the 1470s and were developed to emphasize the primacy of Rome and the papacy. The Perugino image reflects precisely that theme. In a wide piazza in front of the Temple, Christ gives the keys of temporal and spiritual power to the kneeling Peter. The Gospel passage referenced is Jesus’ pronouncement that he will hand over the keys of heaven to Peter (Matthew 16:18–20). Though Matthew’s Gospel records Jesus’ words, the text does not relate the actual handover—that had to be imagined. -

Raffael Santi | Elexikon

eLexikon Bewährtes Wissen in aktueller Form Raffael Santi Internet: https://peter-hug.ch/lexikon/Raffael+Santi MainSeite 63.593 Raffael Santi 3'315 Wörter, 22'357 Zeichen Raffael Santi, auch Rafael, Raphael (ital. Raffaello), irrtümlich Sanzio,ital. Maler, geb. 1483 zu Urbino. Der Geburtstag selbst ist streitig: je nachdem man die vom Kardinal Bembo verfaßte Grabschrift R.s deutet, welche besagt, er sei «an dem Tage, an dem er geboren war, gestorben» («quo die natus est eo esse desiit VIII Id. April MDXX», d. i. 6. April 1520, damals Karfreitag), setzt man den Geburtstag auf den 6. April oder auf den Karfreitag, d. i. 28. März 1483, an. Seine erste künstlerische Unterweisung dankte er dem Vater Giovanni Santi (s. d.), den er jedoch bereits im 12. Jahre verlor, sodann einem unbekannten Meister in Urbino, vielleicht dem Timoteo Viti, mit dem er auch später enge Beziehungen unterhielt. Erst 1499 verließ er die Vaterstadt und trat in die Werkstätte des damals hochberühmten Malers Perugino (s. d.) in Perugia. Das älteste Datum, welches man auf seinen Bildern antrifft, ist das Jahr 1504 (auf dem «Sposalizio», s. unten); doch hat er gewiß schon früher selbständig für Kirchen in Perugia und in Città di Castello gearbeitet. 1504 siedelte Raffael Santi nach Florenz über, wo er die nächsten Jahre mit einigen Unterbrechungen, die ihn nach Perugia und Urbino zurückführten, verweilte. In Florenz war der Einfluß Leonardos und Fra Bartolommeos auf seine künstlerische Vervollkommnung am mächtigsten; von jenem lernte er die korrekte Zeichnung, von diesem den symmetrischen und dabei doch bewegten Aufbau der Figuren. Als abschließendes künstlerisches Resultat seines Aufenthalts in Florenz ist die 1507 für San Fancesco in Perugia gemalte Grablegung zu betrachten (jetzt in der Galerie Borghese zu Rom). -

An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century Copy of Raphael’S Holy Family, C.1518

Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century copy of Raphael’s Holy Family, c.1518. Annie Cornwell, Postgraduate in the Conservation of Easel Paintings Amalie Juel, MA Art History Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a 17th-Century copy of Raphael’s The Holy Family, c. 1518, The Prado Madrid. Introduction to The Project: This report has been written as part of the annual project Conservation and Art Historical Analysis, presented by the Sackler Research Forum at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Seeking to encourage collaboration between art historians and conservators, the scheme brings together two students - one from postgraduate art history and the other from easel paintings conservation - to complete an in-depth research project on a single piece of art. By doing so, the project allows a multifaceted approach combining historical research with technical analysis and, in this case, conservation treatment of the work in question. Focusing on the painting as a physical object with a material history, the project shows the value of combining art history with the more scientific aspects of the field of conservation. The focus of this project is a painting of the Virgin and Child with Saints Anne and John - a copy of Raphael’s Holy Family from the Prado - of unknown artist and date. It is owned by St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Wapping, where it had been recently found in a cupboard underneath the stairs. It came into the Courtauld Conservation Department to be treated by Annie Cornwell in November 2015, at which point it was in quite poor condition. -

7 X 11 Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00119-0 - Classical Myths in Italian Renaissance Painting Luba Freedman Index More information t INDEX Achilles, shield by Hephaistos, 61, 223n23 two versions, Italian and Latin, 223n15 Achilles Tatius on verisimilitude, 94, 98 on grouping of paintings, 172, 242n53 De re aedificatoria on painting depicting the myth of Philomela, on fabulae, 38 188. See also Europa on historiae, 38 translated by Dolce, 172 on paintings in villas, 38 Acrisius, legendary King of Argos, 151 humanistic painting program of, 38, 59 ad fontes, 101 Aldrovandi, Ulisse, Adhemar,´ Jean, 19, 227n90 All the Ancient Statues ...,12 Adonis on antique statues of Adonis and Venus, 114 Death of Adonis by Piombo, 215n4. See also description of Danae,¨ 127, 128 Venus and Adonis description of Europa, 91 Adriani, Giovanni Battista, 152–153, 169, 170, description of Marsyas, 135–136 174 description of Proserpina, 106 Adrian VI (pope from 9 January 1522 to 14 description of statues compared with Lucius’s, September 1523), 44 114 dispenses with antiquities from Rome, 44 on gardens, 153 tutor of Charles V, 246n6 identification of mythological subjects by, 12 Aesop, 197, 200 Alexander the Great, 42 Agostini, Niccolodegli,` 65 armor of, 138 Alamanni, Luigi, Favola di Narcisso and Favola di and Roxana. See Sodoma (Giovanni Antonio Fetonte, 211, 248n48 Bazzi) Alberti, Leon Battista alla franceze. See Warburg, Aby De pictura, 4 all’antica on art practices, 56 accumulated interest in antiquity required for, on brevitas, 190 2, 131 on historia, 58–59 -

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and Background Information 1. Raffaello Santi Born in Urbino, Then a Small but Important C

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and background information 1. Raffaello Santi born in Urbino, then a small but important cultural center of the Italian Renaissance; trained by his father, Giovanni Santi. 2. Influenced by Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo; worked in Florence 1504-08, in Rome 1508-20, where his chief patrons were Popes Julius II and Leo X. 3. Pictorial structures and concepts: the picture plane, linear and atmospheric perspective, foreshortening, chiaroscuro, contrapposto. 4. Painting media a. Tempera (egg binder and pigment) or oil (usually linseed oil as binder); support: wood panel (prepared with gesso ground) or canvas. b. Fresco (painting on wet plaster); cartoon, pouncing, giornata. Selected works 5. Religious subjects a. Marriage of the Virgin (“Spozalizio”), 1504 (oil on roundheaded panel, 5’7” x 3’10”, Pinacoteca de Brera, Milan) b. Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1505 (oil on panel, 44.5” x 34.6”, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) c. Madonna del Cardellino (“Madonna of the Goldfinch”), 1506 (oil on panel, 3’5” x 2’5”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) d. Virgin and Child with St. Sixtus and St. Barbara (“Sistine Madonna”), 1512-13 (oil on canvas, 8’8” x 6’5”, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden) 6. Portraits a. Agnolo Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) b. Maddalena Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) c. Cardinal Tommaso Inghirami, c. 1510-14 (oil on panel, 2’11 ¼” x 2’, Pitti Palace, Florence) d. Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514-15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) e. -

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels, a copy of Raphael Technical report, restoration and new light on its history and attribution José de la Fuente Martínez José Luis Merino Gorospe Rocío Salas Almela Ana Sánchez-Lassa de los Santos This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 2 and 5-19 © Groeningemuseum, Brugge: fig. 21 © Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, Bruxelles: fig. 20 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: fig. 55 © RMN / Gérard Blot-Jean Schormans: fig. 3 © RMN / René-Gabriel Ojéda: fig. 4 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17-64. Sponsored by: 2 fter undergoing a painstaking restoration process, which included the production of a detailed tech- nical report, the Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels1 A[fig. -

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile «... non fu superato in nulla, e sembra radunare in sé tutte le buone qualità degli antichi». Così si esprime, a proposito di Raffaello Sanzio, G.P. Bellori – tra i più convinti ammiratori dell’artista nel ’600 –, un giudizio indicativo dell’incontrastata preminenza ormai riconosciuta al classicismo raffaellesco. Nato a Urbino (1483) da Giovanni Santi, Raffaello entra nella bottega di Pietro Perugino in anni imprecisati. L’intera produzione d’esordio è all’insegna di quell’incontro: basti osservare i frammenti della Pala di San Nicola da Tolentino (Città di Castello, 1500) o dell’Incoronazione di Maria (Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, 1503). Due cartoni accreditano, ad avvio del ’500, il coinvolgimento nella decorazione della Libreria Piccolomini (Duomo di Siena). Lo Sposalizio della Vergine (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera, 1504), per San Francesco a Città di Castello (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera), segna un decisivo passo di avanzamento verso la definizione dello stile maturo del Sanzio. Il soggiorno a Firenze (1504-08) innesca un’accelerazione a tale processo, favorita dalla conoscenza dei tra- guardi di Leonardo e Michelangelo: lo attestano la serie di Madonne con il Bambino, i ritratti e le pale d’altare. Rimonta al 1508 il trasferimento a Roma, dove Raffaello è ingaggiato da Giulio II per adornarne l’appartamento nei Palazzi Vaticani. Nella prima Stanza (Segnatura) l’urbinate opera in autonomia, mentre nella seconda (Eliodoro) e, ancor più, nella terza (Incendio di Borgo) è affiancato da collaboratori, assoluti responsabili dell’ultima (Costantino). Il linguaggio raffaellesco, inglobando ora sollecitazioni da Michelangelo e dal mondo veneto, assume accenti rilevantissimi, grazie anche allo studio dell’arte antica. -

Peripheral Packwater Or Innovative Upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, C.1390 - 1527

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 Beverley N. Lyle (2008) https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/e2e5200e-c292-437d-a5d9-86d8ca901ae7/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Lyle, B N (2008) Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 PhD, Oxford Brookes University WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR Peripheral packwater or innovative upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, c.1390 - 1527 Beverley Nicola Lyle Oxford Brookes University This work is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirelnents of Oxford Brookes University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September 2008 1 CONTENTS Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Preface 6 Chapter I: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: The Dominance of Foreign Artists (1390-c.1460) 40 Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Local School (c.1450-c.1480) 88 Chapter 4: The Supremacy of Local Painters (c.1475-c.1500) 144 Chapter 5: The Perugino Effect (1500-c.1527) 197 Chapter 6: Conclusion 245 Bibliography 256 Appendix I: i) List of Illustrations 275 ii) Illustrations 278 Appendix 2: Transcribed Documents 353 2 Abstract In 1400, Perugia had little home-grown artistic talent and relied upon foreign painters to provide its major altarpieces. -

Znanost Za Umetnost

CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.025.3"21"(082)(0.034.2) 7.025.4"20"(082)(0.034.2) ZNANOST za umetnost : konservatorstvo in restavratorstvo danes : zbornik prispevkov mednarodnega simpozija = Science in art : conservation and restoration today : international symposium proceedings / [znanstvena besedila Marin Berovič ... [et al.] ; glavni urednici Tamara Trček Pečak, Nada Madžarac ; prevodi iz angleščine v slovenščino Breda Misja ... [et al.], prevodi spremnih besedil Tamara Soban]. - Ljubljana : Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine, 2013 ISBN 978-961-6902-59-5 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Berovič, Marin 3. Trček Pečak, Tamara 270068992 Glavni urednici | Editors-in-chief Tamara Trček Pečak, Nada Madžarac Uredniški odbor | Board of editors Tina Buh, Jo Kirby, Nada Madžarac, Miladi Makuc Semion, Tamara Soban, Tamara Trček Pečak Recenzentki | Board of Reviewers: Jo Kirby, Miladi Makuc Semion Znanstvena besedila | Scientific texts Marin Berovič, Rachel Billinge, Christopher Holden, Jo Kirby, Polonca Ropret, Denis Vokić, Ulrich Weser Tuji avtorji so znanstvena besedila posredovali v angleščini, slovenska avtorja pa v obeh jezikih. All scientific texts were written in English; the Slovenian authors also provided their texts in Slovenian. Prevodi iz angleščine v slovenščino | Translations into Slovenian Breda Misja, Irena Sajovic, Tamara Soban, Suzana Stančič Prevodi spremnih besedil | Translations of introductory texts Tamara Soban Lektoriranje slovenskih besedil | Slovenian language editing Vlado Motnikar Lektoriranje angleških besedil | English language editing Jo Kirby Uredniške korekture pred tiskom | Editorial revise before printing Mateja Neža Sitar Grafično oblikovanje (2011/2012) | Graphic Design (2011/2012) Jelena Kauzlarić Izdal | Published by Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia Zanj | Publishing Executive dr. -

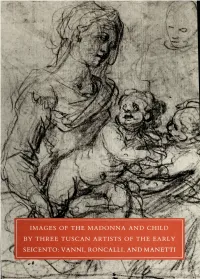

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

Comunicato Stampa Inglese

PRESS RELEASE For the first time in Rome, at the Musei Capitolini Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and rediscovery From 19th July to 3rd November 2019 at Palazzo Caffarelli, a celebration of one of the greatest stars of the Italian Renaissance Rome, 18th July 2019 - as the 500th anniversary of the death of Raphael draws near, the Musei Capitolini pays tribute to Luca Signorelli (Cortona, around 1450 - 1523) in the rooms of the Palazzo Caffarelli with the exhibition, Luca Signorelli and Rome . Oblivion and rediscovery . For the first time in Rome , this is a celebration of one of the Italian Renaissance’s leading lightsHis remarkable artistic star was obscured only by the unforeseeable arrival of two giants of the following generation: Michelangelo (1475-1564) and Raphael (1483-1520), who were, however, inspired by the master of Cortona to reach the unsurpassed pinnacle of painting that their contemporaries attribute to them. In fact, as Giorgio Vasari wrote, Luca Signorelli “ was more famous in his day, and his works were held in higher esteem, than any other previous artist no matter the period ”. The exhibition, curated by Federica Papi and Claudio Parisi Presicce , is supported by Roma Capitale, Assessorato alla Crescita culturale - Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali , and organised by Zètema Progetto Cultura. The catalogue is edited by De Luca Editori d’Arte. Showing a careful selection of around 60 prestigious works from Italian and foreign collections, many of which are exhibited for the first time in Rome , the exhibition highlights the historical artistic context in which the artist made his first visit to Rome and offers new interpretations on the artist’s direct and indirect ties with Rome .