Report 2018-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institutional Effectiveness Plan 2008-2009

INSTITUTIONAL EFFECTIVENESS PLAN 2008-2009 A Comprehensive System for Improving Institutional Effectiveness at Coahoma Community College 3rd Publication Published by: Office of Institutional Effectiveness 3240 Friars Point Road Clarksdale, MS 38614 662-621-4201 DATE: August 2009 Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 President’s Welcome, Mission Statement and Goals, and Background of Institutional Effectiveness Plan .......................... 7 Section 1 – Educational Programs Accounting Technology ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Associate Degree Nursing Program .................................................................................................................... 18 Barber/Stylist ......................................................................................................................................................... 24 Business and Office Systems Technology .......................................................................................................... 28 Certified Nursing Assistant ................................................................................................................................... 33 Child Development Technology ......................................................................................................................... -

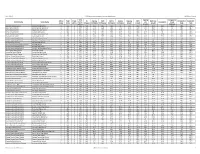

10/11/2018 2018 Mississippi Statewide Accountability Results 1000 Point Schools District Name School Name Official Grade Total P

10/11/2018 2018 Mississippi Statewide Accountability Results 1000 Point Schools Total Reading College and Official Total Grade EL Reading Math History Science Reading Math Math Low Participation Graduation District Name School Name Points Low Acceleration Career Grade Points with EL Progress Proficiency Proficiency Proficiency Proficiency Growth Growth Growth Rate Rate with EL Growth Readiness Aberdeen School District Aberdeen High School B 652 B 652 N/A 41.3 38.7 50.6 50 74.6 86.8 79.4 87.5 60.3 20.3 98.2 76.5 Alcorn School District Alcorn Central High School C 644 C 644 N/A 57.3 35.8 58.1 74.1 66.3 57.8 53.4 80.4 72.7 50 98.1 82.7 Alcorn School District Biggersville High School C 601 C 601 N/A 35.6 40 58.3 77.4 43.1 64.5 47 66.7 50.4 31.4 99.4 97.5 Alcorn School District Kossuth High School A 801 A 801 N/A 53.9 67.2 59.3 80.7 81.4 95.8 81.7 110.8 76 44.2 98 89.9 Amite County School District Amite County High School F 466 F 466 N/A 20.7 19.2 34.3 43.8 44.5 44.2 55.1 52.5 67.8 21 96.5 73.3 Amory School District Amory High School B 725 B 725 N/A 62.5 57.7 69.9 73.6 79.1 77.8 62.5 81.7 72.5 43.5 99.5 87.2 Attala County School District Ethel Attendance Center D 550 D 550 N/A 34.7 30.5 52.4 55.8 51.3 53.9 64.8 51.4 72.3 43.5 100 75.9 Attala County School District Mcadams Attendance Center F 478 F 478 N/A 27.5 14.1 51.9 31.3 49.7 32.2 59.1 40 59.3 17.5 99.2 87.9 Baldwyn School District Baldwyn High School C 586 C 586 N/A 38.6 48.3 70.7 72.4 54 55.1 53.6 34.5 69.4 41.1 98.7 87.7 Bay St Louis Waveland School District Bay High School B 737 B 737 -

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results Carey M. Wright, Ed.D. State Superintendent of Education November 2019 Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results: November 2019 A Joint Publication Office of Accountability • Dr. Paula Vanderford, Chief Accountability Officer • Dr. Jackie Sampsell, State Assessment Director • Melissa Beck, K-3 Assessment Coordinator Office of Academic Education • Dr. Nathan Oakley, Chief Academic Officer • Dr. Tenette Smith, Executive Director of Elementary Education and Reading • Dr. Jill Dent, Early Childhood Director • Kristen Wells, State Literacy Director (K-12) • Laurie Weathersby, Director or Student Intervention Services For questions related to the administration of the Kindergarten Readiness Assessment please contact: Melissa Beck, K-3 Assessment Coordinator Office of Student Assessment [email protected] The Mississippi State Board of Education, the Mississippi Department of Education, the Mississippi School for the Arts, the Mississippi School for the Blind, the Mississippi School for the Deaf, and the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science do not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, color, religion, national origin, age, or disability in the provision of educational programs and services or employment opportunities and benefits. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries and complaints regarding the non-discrimination policies of the above-mentioned entities: Director, Office of Human Resources Mississippi Department of Education 359 North West Street Suite 203 Jackson, Mississippi 39201 (601) 359-3511 Mississippi Department of Education Office of Student Assessment Page 2 of 21 Scale Score Explanation and Kindergarten Readiness Performance Levels The Kindergarten Readiness Assessment will provide parents, teachers, and early childhood providers with a common understanding of what children know and are able to do upon entering school. -

2010-2011 Factbook

FACTBOOK 2010-2011 YEAR OF GREEN OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH & PLANNING FACTBOOK 2010-2011 ERIC ATCHISON, RESEARCH & INFORMATION SPECIALIST MARCIE BEHRENS, ASSESSMENT & PLANNING SPECIALIST SUZANNE SIMPSON, DIRECTOR OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH & PLANNING DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The Delta State University Factbook is an annual publication that provides a ready source of information to answer questions frequently asked about the University. This edition contains a statistical overview of operations for the 2010-2011 academic year. Included is information, both past and present, concerning enrollment, student characteristics, faculty characteristics, revenue, and expenditures. Its primary purpose is to promote understanding for those seeking information about Delta State University. During the summer of 2010, Delta State University hosted its first Teach for America Summer Institute which brought over 800 TFA corps members and staff to the campus. During the five-week training program each corps member was granted the option to enroll in three diferent CUR courses. The TFA Institute registered 504 students for these courses. These figures are included in the fall enrollment report and were submitted to IHL as part of the official university headcount. An extra page has been added to Section III (Enrollment) which provides a breakdown of the TFA student information and footnotes have been provided to inform the large changes observed for the trend data. Also, Section IV (Credit Hour Production) includes credit hours produced by the TFA Summer Institute participants. This information is footnoted as well on the selected pages. Most of the information in this edition was obtained from statistical reports published by the Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher Learning, State of Mississippi. -

4370 [email protected] E

Corlis L. Snow Delta State University Contact Information Box 3112 Cleveland, MS 38732 (662) 846 – 4370 [email protected] Education/Certifications ABD elementary education, The University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi, 2006 MS elementary education, Delta State University, Cleveland, Mississippi, 2001. BS elementary education, Delta State University, Cleveland, Mississippi, 1999. ADN nursing, Mississippi Delta Community College, Moorhead, Mississippi, 1985. Work History Instructor within the Elementary Education Department of Teacher Education at Delta State University from August 2001 to present. Teacher, second grade, Ray Brooks School, Benoit, Mississippi, August 1999 to May 2001. Registered Nurse, Home Health Care Agencies, June 1985 to December 1997. Teaching Load Fall 2005 CEL 314 Early literacy Instruction I CEL 315 Early Literacy Instruction II CEL 317 Principles and Techniques of Teaching in Early Childhood CEL 496 Supervised six student teachers Spring 2006 CEL 314 Early literacy Instruction I CEL 315 Early Literacy Instruction II (2 sections) CEL 317 Principles and Techniques of Teaching in Early Childhood Scholarship Snow, C. & Allen-Bradley, J. (2005). I don’t know nuttin’ about no engineer: The need for building background knowledge. Delta Education Journal, 2, 7- 14. Work Supporting P-12 Education Developed and presented an interactive workshop session that engaged participants in instructional strategies to increase young children’s vocabulary development. The workshop was given at the Early Childhood Conference, which took place at DSU. Early childhood faculty and staff from local communities participated in hands-on experiences and were given research findings regarding vocabulary development. Coordinated and participated in a group presentation that engaged P-12 teachers in instructional strategies for vocabulary development. -

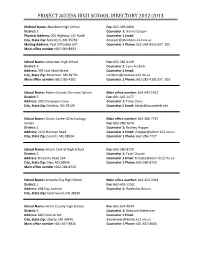

Project Access High School Directory 2012-2013

PROJECT ACCESS HIGH SCHOOL DIRECTORY 2012-2013 0School Name: Aberdeen High School Fax: 662-369-6004 District: 2 Counselor 1: Donna Cooper Physical Address: 205 Highway 145 North Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Aberdeen, MS 39730 [email protected] Mailing Address: Post OfficeBox 607 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-369-8933 EXT. 205 Main office number: 662-369-8933 School Name: Ackerman High School Fax: 662-285-4149 District: 4 Counselor 1: Lynn Scribner Address: 393 East Main Street Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Ackerman, MS 39735 [email protected] Main office number: 662-285-4101 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-285-4101 EXT. 103 School Name: Adams County Chrisitian School Main office number: 601-442-1422 District: 5 Fax: 601-442-1477 Address: 300 Chinquapin Lane Counselor 1: Tracy Davis City, State Zip: Natchez, MS 39120 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] School Name: Alcorn Career &Technology Main office number: 662-286-7727 Center Fax: 662-286-5674 District: 2 Counselor 1: Rodney Hopper Address: 2101 Norman Road Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Corinth, MS 38834 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-7727 School Name: Alcorn Central High School Fax: 662-286-8720 District: 2 Counselor 1: Tazel Choate Address: 8 County Road 254 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Glen, MS 38846 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-8720 Main office number: 662-286-8720 School Name: Amanda Elzy High School Main office number: 662-453-3394 District: 1 Fax: 662-453-1258 Address: 604 Elzy Avenue Counselor 1: -

2019 Comprehensive Support and Improvement Schools (CSI)

2019 Comprehensive Support and Improvement Schools (CSI) School ID District_Name School_Name Grade Subgroup/Reason SI New or Continued Status 1420-028 Clarksdale Municipal School District Geo H Oliver Visual/Perf. Arts D Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 1420-024 Clarksdale Municipal School District Oakhurst Intermediate Academy F Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 0614-024 Cleveland School District Nailor Elementary School D Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 1400-004 Coahoma County School District Coahoma County Jr/Sr High School D Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 6811-012 East Tallahatchie Consolidated School District Charleston Middle School F Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 7620-008 Greenville Public School District Armstrong Elementary School A Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2611-018 Holmes Consolidated School District William Dean Jr. Elementary School F Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2700-004 Mississippi Achievement School District Ida Greene Elementary (formerly Ida Greene Lower Elementary) F Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2700-006 Mississippi Achievement School District O M Mc Nair Middle School (formerly Humphreys County Jr. High) D Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2520-010 Jackson Public School District Blackburn Middle School D Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2520-014 Jackson Public School District Brinkley Middle School F Lowest 5% of Title I A schools CSI Continued 2520-018 Jackson Public School District -

JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS in MISSISSIPPI Geoffry Alan Haines University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2007 JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI Geoffry Alan Haines University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Haines, Geoffry Alan, "JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI" (2007). Dissertations. 1312. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1312 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI by Geoffry Alan Haines A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: December 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY GEOFFRY ALAN HAINES 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The University of Southern Mississippi JOB SATISFACTION AMONG HIGH SCHOOL PRINCIPALS IN MISSISSIPPI by Geoffry Alan Haines Abstract of -

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results

Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results Carey M. Wright, Ed.D. State Superintendent of Education June 2016 Kindergarten Readiness Assessment Results: June 2016 A Joint Publication Division of Research and Development • Dr. J. P. Beaudoin, Chief Research and Development Officer • Walt Drane, Executive Director of Student Assessment and School/District Accountability • Vincent Segalini, Assessment Director • Patrice Williams, MKAS2 State Coordinator Office of the Chief Academic Officer • Dr. Kim Benton, Chief Academic Officer • Dr. Nathan Oakley, Executive Director of Elementary Education and Reading • Dr. Jill Dent, Early Childhood Director • Dr. Kymyona Burk, State Literacy Director (K-12) • Dr. Tenette Smith, State Literacy Coordinator (K-3) • Robin Lemonis, Director of Student Intervention Services The Mississippi State Board of Education, the Mississippi Department of Education, the Mississippi School for the Arts, the Mississippi School for the Blind, the Mississippi School for the Deaf, and the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science do not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, color, religion, national origin, age, or disability in the provision of educational programs and services or employment opportunities and benefits. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries and complaints regarding the non-discrimination policies of the above mentioned entities: Director, Office of Human Resources Mississippi Department of Education 359 North West Street Suite 203 Jackson, Mississippi 39201 (601) 359-3511 Division of Research and Development Office of the Chief Academic Officer Page 2 of 26 Scale Score Explanation and Kindergarten Readiness Performance Levels The Kindergarten Readiness Assessment will provide parents, teachers, and early childhood providers with a common understanding of what children know and are able to do upon entering school. -

2015 3Rd Grade Reading Assessment Initial Results

MKAS2 3rd Grade Summative Assessment Results May 2015 3rd Grade Reading Summative Assessment Results Overview and Scale Score (SS) Explanation 3rd Grade Reading Summative Assessment Spring 2015 Results Summary Minimum Passing Score 926 State Scale Score Average 980 Students Scoring at or Above 926 32,219 Students (85.17%) Students Scoring Below 926 5,612 Students (14.83%) 926 Cut Score Explanation The 3rd Reading Summative Assessment scale score of 926 is the minimum score associated with readiness for 4th grade based on the requirements of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act. In accordance with Mississippi Code § 37-177-9, students must be above the “lowest achievement level in reading” to be promoted to 4th grade. This score was derived as a result of a standard setting process which included expert judgments by a panel of educators, parents, and community members from across the state and subsequent review by the Mississippi Department of Education and Mississippi’s National Technical Advisory Committee as well as other nationally known experts. Performance Level Descriptors PASS (926-1200 Scale Score): A student who scores a 926 or above has acquired the minimum reading skills needed to learn 4th grade standards. Students who score within a close range of the cut score, however, still need additional intervention and supports in the following areas: • Answer questions, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answer • Determine the central message, lesson, moral in literary text • Determine the main idea and recount key details in informational text • Identify character traits as they relate to the story • Refer to parts of stories, dramas, and poems using terms such as chapter, scene, and stanza • Locate information relevant to a given topic using key words, headings, bold print, etc. -

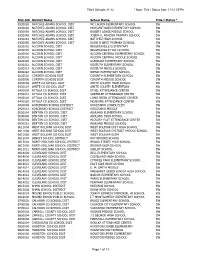

Title I Schools 11-12 * Note: Title I Status from 11-12 CFPA

Title I Schools 11-12 * Note: Title I Status from 11-12 CFPA Dist-Sch District Name School Name Title I Status * 0130020 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST MC LAURIN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0130028 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST MORGANTOWN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0130036 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST ROBERT LEWIS MIDDLE SCHOOL SW 0130040 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST JOSEPH L FRAZIER PRIMARY SCHOOL SW 0130044 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST NATCHEZ HIGH SCHOOL SW 0130056 NATCHEZ-ADAMS SCHOOL DIST SUSIE B WEST PRIMARY SCHOOL SW 0200002 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST BIGGERSVILLE ELEMENTARY SW 0200004 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST BIGGERSVILLE HIGH SCHOOL SW 0200006 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST ALCORN CENTRAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0200010 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST ALCORN CENTRAL MIDDLE SCHOOL SW 0200020 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST GLENDALE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0200022 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST KOSSUTH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0200023 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST KOSSUTH MIDDLE SCHOOL SW 0200028 ALCORN SCHOOL DIST RIENZI ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0220002 CORINTH SCHOOL DIST CORINTH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SW 0220006 CORINTH SCHOOL DIST CORINTH MIDDLE SCHOOL SW 0300008 AMITE CO SCHOOL DIST AMITE COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL SW 0300014 AMITE CO SCHOOL DIST AMITE COUNTY ELEMENTARY SW 0400008 ATTALA CO SCHOOL DIST ETHEL ATTENDANCE CENTER SW 0400012 ATTALA CO SCHOOL DIST GREENLEE ATTENDANCE CENTER SW 0400016 ATTALA CO SCHOOL DIST LONG CREEK ATTENDANCE CENTER SW 0400020 ATTALA CO SCHOOL DIST MCADAMS ATTENDANCE CENTER SW 0420008 KOSCIUSKO SCHOOL DISTRICT KOSCIUSKO LOWER ELEM SW 0420012 KOSCIUSKO SCHOOL DISTRICT KOSCIUSKO MIDDLE SW 0500004 BENTON CO SCHOOL DIST ASHLAND -

Governor Musgrove's Classroom Technology Task Force, Phase 1 Allocations

A BC 1 Governor Musgrove's Classroom Technology Task Force, Phase 1 Allocations 2 3 District Name School Name Allocated 4 Aberdeen School District Aberdeen Elementary School 10 5 Aberdeen School District Aberdeen High School 8 6 Aberdeen School District Aberdeen Middle School 4 7 Aberdeen School District Vine Street Elementary School 5 8 Aberdeen School District Aberdeen Learning Center 5 9 Alcorn County School District Biggersville Elementary School 2 10 Alcorn County School District Biggersville High School 6 11 Alcorn County School District Alcorn Central High School 1 12 Alcorn County School District Alcorn Central Middle School 9 13 Alcorn County School District Glendale Elementary School 9 14 Alcorn County School District Kossuth Elementary School 21 15 Alcorn County School District Kossuth High School 22 16 Alcorn County School District Rienzi Elementary School 4 17 Alcorn County School District Alclorn County Vocational Complex 3 18 Amite County School District Amite County High School 2 19 Amite County School District Liberty Elementary School 8 20 Amory School District Amory Elementary School 6 21 Amory School District Amory High School 12 22 Amory School District Amory Middle School 17 23 Amory School District Amory Vocational Technical Complex 3 24 Attala County School District Ethel Attendance Center 2 25 Attala County School District Greenlee Attendance Center 14 26 Attala County School District Long Creek Attendance Center 18 27 Attala County School District McAdams High School 7 28 Baldwyn Public Schools Baldwyn Elementary School 2 29 Baldwyn Public Schools Baldwyn High School 24 30 Baldwyn Public Schools Baldwyn Middle School 22 31 Bay St.