Whistleblowing a Suitable Instrument to Improve Public Corporate Governance?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ii Main Part

UBS: Wealth Management BACHELOR THESIS (CASE STUDY) UBS: THE WAY TO BECOMING A GLOBAL PLAYER IN WEALTH MANAGEMENT "On which critical foundational factors are UBS and its leadership in Wealth Management built and with which major event is the current UBS crisis to be explained?" AUTHOR: ALAIN NTJAM OLTEN, AUGUST 9, 2013 SUPERVISOR: DR. KONDOVA GALIA INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT Alain Ntjam August 2013 1 UBS: Wealth Management Abstract Purpose: The objective of this bachelor thesis is to analyze in a case study manner, how the big Swiss bank UBS evolved and became a global player in wealth management. The guiding research question is: ‘On which critical foundational factors is UBS and its leadership in wealth management built, and with through which major event can the current UBS crisis be explained? Methodology and approach: The first analytical tool of this paper is the PEST analysis that aims to find out which environmental condition in the 1990s facilitated the UBS merger and how it came to the merger. The motives for its direction of growth will be analyzed to understand the bank's strategic intent in regards to wealth management and the bank's growth path. The next chapter seeks to understand the corporate ‘one firm strategy’ of UBS, how it relates to its organizational chart and which role the North American wealth management market plays within the organization. Further a comparison to Credit Suisse is made. The last chapter within the main part of the thesis attempts to sort out the significant activities of the value chain which creates or adds wealth management value for clients. -

Litigating the Holocaust: a Consistent Theory in Tort for the Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 27 Issue 3 Article 4 4-15-2000 Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations Derek Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Derek Brown Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations , 27 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (2000) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol27/iss3/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations I. INTRODUCTION Survivors of the Holocaust have repeatedly attempted, with little apparent success, to recover the assets their families deposited in Swiss banks prior to World War II. Considering the claimants' subsequent-yet understandable lack of documentation,- until now these survivors have had to rely solely on the banks' promises to expedite the return of these "dormant accounts" to their rightful owners.' Reliance on such promises, however, quickly evaporated with the public disclosure of one man's experience: Christoph Meili.4 A security guard for the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Meili became an international figure early in 1997. -

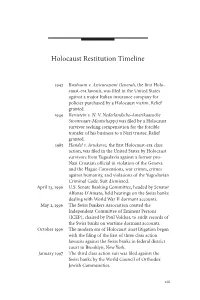

Holocaust Restitution Timeline

Holocaust Restitution Timeline 1942 Buxbaum v. Assicurazioni Generali, the first Holo- caust-era lawsuit, was filed in the United States against a major Italian insurance company for policies purchased by a Holocaust victim. Relief granted. 1949 Bernstein v. N. V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij was filed by a Holocaust survivor seeking compensation for the forcible transfer of his business to a Nazi trustee. Relief granted. 1985 Handel v. Artukovic, the first Holocaust-era class action, was filed in the United States by Holocaust survivors from Yugoslavia against a former pro- Nazi Croatian official in violation of the Geneva and the Hague Conventions, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and violations of the Yugoslavian Criminal Code. Suit dismissed. April 23, 1996 U.S. Senate Banking Committee, headed by Senator Alfonse D’Amato, held hearings on the Swiss banks dealing with World War II dormant accounts. May 2, 1996 The Swiss Bankers Association created the Independent Committee of Eminent Persons (ICEP), chaired by Paul Volcker, to audit records of the Swiss banks on wartime dormant accounts. October 1996 The modern era of Holocaust asset litigation began with the filing of the first of three class action lawsuits against the Swiss banks in federal district court in Brooklyn, New York. January 1997 The third class action suit was filed against the Swiss banks by the World Council of Orthodox Jewish Communities. xiii xiv Holocaust Restitution Timeline January 8, 1997 Christoph Meili discovered the Union Bank of Switzerland attempting to shred pre–World War II financial documents. March 25, 1997 French Prime Minister Alain Juppe created the Prime Minister’s Office Study Mission into the Looting of Jewish Assets in France (“Mattéoli Commission”) to study various forms of theft of Jewish property during World War II and the postwar efforts to remedy such theft. -

NZZ On/I Ne.' English Window

.-."_.---~--- .._.._-----.=_:: .._-_ .. -'-_"J~ ~ NZZ on/i ne.' English Window 19.04.1998 InternationalNews I Editorialson WorldAffairsI Back~U11donWorldAffairsI NewsaboutS\\'itzedandI 5wisi bJWtr~ Weekin ReviO;'w I SWi56 StockMarketReportI SwissBusinessAbstractsI En;:lish Window Frontpagc . ;:go .'.' , ~ ~~ • ~,.." I r ~ '~." MootrecentBa~U11d I PreviousBac~d6 I. Dos~~~~1 h' I" . English Wsndow -.' .... " .. -. NZZ B.ckground on World Affairs February 1998 J News, , ....Ticker- -~-' - .-' ~......,..•.~, '. -, ,., NZZ-Archiv ~ The Sensation Hunter """. ' •• ,'~. , ~ ~.•• r .. ""..Service.'.'.-." ..~..I The Dubious Devices of Class-Action Attorney Edward Fagan r <";'.TAnzeigcn•.•. ' '" '" .',.7, Mail/Leserdiernt••. " .• ~•• N .•• '\, ..••• "_ •• ! byNikos Tzermias" Suchen I New York attorney Edward Fagan has attracted a great deal of attention.with his crass-action "Hitf~l~de~'"" " '"I suits against Swiss banks and againstl6 European insurance companies. But U.S. judges have ~~ '. ' -' •• '. _·f ,~.' ''''. NIZ-Sites I also warned him several times against "frivolous litigation" and family members of the victims of an airline crash have called him an "ambulance chaser." Ti~s<>';:;! For the past few months the World Trade Center, famous status symbol of American capitalism, has had a new tenant. The office on the 81st floor of one of the mighty Twin Towers at the southern tip of Manhattan seems to have some affinity with Switzerland. On the wall of the waiting room hang four clocks, showing the local time in Tokyo, New York, London ~d Zurich. But Suite 8101 does not house the branch office of some Swiss company. Lbdged' at that dizzying height is New York attorney Edward Fagan, who has instituted class-action lawsuits in the name of Holocaust survivors against Swiss banks and against 16 European insurance companies, and more recently filed charges of slander against the Union Bank of Switzerland on behalf of former Swiss bank security guard Christoph Meili and his wife Giuseppina. -

The Holocaust Restitution Movement in Comparative Perspective

The Holocaust Restitution Movement in Comparative Perspective By Michael J. Bazyler* I. INTRODUCTION This article examines the use of civil litigation in the United States to deal with human rights abuses committed during World War II. The specific scena- rio examined is the Holocaust restitution movement in the United States, whose aim is to obtain financial restitution from European and American corporations 1 for their nefarious wartime activities. This article also examines other move- ments aiming to bring justice for historical wrongs that arose as a direct result of the successes achieved in the Holocaust restitution arena. Three such prominent movements are: (1) the lawsuits filed in the United States by victims of slave labor by Japan and Japanese industry during World War II; (2) the recent claims in U.S. courts of the survivors of Armenian genocide for reimbursement of the insurance proceeds paid by their deceased relatives; and (3) the emerging call for African-American reparations stemming from slavery. All of these move- ments are a direct outgrowth of the successful claims achieved in the Holocaust restitution arena. Finally, this article discusses the emerging debate about the propriety of seeking monetary damages for historical wrongs, especially as it has now emerged in the sphere of Holocaust-era litigation. The fact that American courts are being used today to deal with wrongs committed during World War II, over one-half century after the events took place, is astounding. In the history of American litigation, no class of cases has ever appeared in which so much time had passed between the wrongful act and the filing of the lawsuit. -

Chronology: Switzerland and the Second World War

Chronology: Switzerland and the Second World War Put together by the Parliamentary Services 1. Brief Survey 1934-1994 1934 Introduction of bank secrecy 1939- Second World War (for the chronology of events during this period, 45 refer to tables of events in the relevant literature) 1946 Federal Decree concerning the approval of the financial agreement concluded in Washington (the Washington Agreement, with message of the Federal Council, the Federal Decree, debates in the National Council and in the Council of States, and several newspaper articles) 1947 Short parliamentary question Meister: concerning valuable objects which might have found their way from Auschwitz to Switzerland 1949 Compensation Agreement of Switzerland with Poland (see also: Hug/Perrenoud Report, 1996) 1950 Compensation Agreement of Switzerland with Hungary (see also: Hug/Perrenoud Report, 1996) 1950 Interpellation of Werner Schmid. Heirless assets 1951 Short parliamentary question of Philipp Schmid 1957 Ludwig Report: Switzerland’s Refugee Policy from 1933 to the Present (1957) 1959 Motion by Huber. Assets of missing foreigners 1959 The Swiss Bankers Association argues against a registration decree on « heirless assets ». The assets without known beneficiary amount to only something like 900,000 francs. (information according to the NZZ- Fokus, Nr.2, Feb., 1997) 1962 Federal Decree on Assets situated in Switzerland belonging to Foreigners or Stateless Persons Persecuted for Reasons of Race, Religion, or Political Beliefs, approved on 20 December 1962 1962 The task -

The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action

Michigan Law Review Volume 102 Issue 6 2004 Justice for the Collective: The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action Paul R. Dubinsky New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Legal Remedies Commons Recommended Citation Paul R. Dubinsky, Justice for the Collective: The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action, 102 MICH. L. REV. 1152 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol102/iss6/9 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE FOR THE COLLECTIVE: THE LIMITS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS CLASS ACTION Paul R. Dubinsky* HOLOCAUST JUSTICE: THE BATTLE FOR RESTITUTION IN AMERICA'S COURTS. By Michael J. Bazyler. New York: New York University Press. 2003. Pp. xix, 411. Cloth, $34.95. IMPERFECT JUSTICE: LOOTED ASSETS, SLAVE LABOR, AND THE UNFINISHED BUSINESS OF WORLD wAR II. By Stuart E. Eizenstat. New York: Public Affairs. 2003. Pp. xi, 401. Cloth, $30. The class action lawsuit is our grand procedural experiment in collective justice. As against the U.S. legal system's strong orientation toward individual rights rather than group rights, the class action is a countercurrent. Through Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, large numbers of previously unaffiliated individuals can proceed in federal court as a group, litigating through representatives. -

Litigating the Holocaust: a Consistent Theory in Tort for the Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations , 27 Pepp

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 27 | Issue 3 Article 4 4-15-2000 Litigating The oloH caust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The rP ivate Enforcement of Human Rights Violations Derek Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Derek Brown Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations , 27 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (2000) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol27/iss3/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected] , [email protected]. Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations I. INTRODUCTION Survivors of the Holocaust have repeatedly attempted, with little apparent success, to recover the assets their families deposited in Swiss banks prior to World War II. Considering the claimants' subsequent-yet understandable lack of documentation,- until now these survivors have had to rely solely on the banks' promises to expedite the return of these "dormant accounts" to their rightful owners.' Reliance on such promises, however, quickly evaporated with the public disclosure of one man's experience: Christoph Meili.4 A security guard for the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Meili became an international figure early in 1997. -

Paved with Good Intentions: the Development of German and American Holocaust-Era Looted Art Restitution Institutions

Paved with Good Intentions: The Development of German and American Holocaust-era Looted Art Restitution Institutions Alyssa Stokvis-Hauer A Thesis in The Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (Art History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada January 2018 Alyssa Stokvis-Hauer, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Alyssa Stokvis-Hauer Entitled: Paved with Good Intentions: The Development of German and American Holocaust-era Looted Art Restitution Institutions and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Art History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ______________________________________ Chair Elaine Cheasley Paterson _____________________________________ Examiner Loren Lerner _____________________________________ Supervisor Catherine MacKenzie Approved by: __________________________________________ Kristina Huneault, Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ Rebecca Taylor Duclos, Dean of Faculty of Fine Arts Date: ___________________________ Abstract Paved with Good Intentions: The Development of German and American Holocaust-era Looted Art Restitution Institutions Alyssa Stokvis-Hauer This thesis presents insights into how conceptualizing and pursuing Nazi-looted art and cultural heritage restitution has changed since 1945 in the United States and Germany. The text presents historical and institutional analyses of the two major restitution institutions in these countries; the New York Financial Service Department’s Holocaust Claims Processing Office (HCPO), and the Magdeburg-based federal institution known widely as the German Lost Art Foundation, or more correctly as the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste, formerly the Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste located first in Bremen and then Magdeburg. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 3, 1997

June 3, 1997 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE S5219 for up to 10 minutes as if in morning released by the Union Bank and the po- In the letter the prosecutor says, ba- business. lice authorities. sically, that ``we intend,'' and I quote, The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without I have just recently written to the ``to bring a charge'' against Mr. Meili. objection, it is so ordered. local prosecutor, and in that letter of They are going to charge Mr. Meili Mr. D'AMATO. Mr. President, first of May 15 I said, basically, are you still with criminal conduct, not the bank all, let me thank Senator HUTCHINSON threatening to prosecute Mr. Meili? I which shredded the records. And they for being so gracious in permitting me ask that the full text of that letter be want Mr. Meili to come back to Swit- this opportunity because I know he had printed in the RECORD. zerland for another interview. Mr. asked to speak earlier. There being no objection, the letter Meili's lawyer, Mr. Bosonnet, writing f was ordered to be printed in the to a lawyer who is representing Mr. RECORD, as follows: Meili because Mr. Meili is here in hid- VIOLATION OF SWISS BANK U.S. SENATE, COMMITTEE ON BANK- ing, has advised him not to come back SECRECY LAWS ING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AF- to Switzerland because he would face Mr. D'AMATO. Mr. President, I rise FAIRS, not only persecution but prosecution Washington, DC, May 15, 1997. today to discuss the case of Christoph and harassment. Mr. PETER COSANDEY, Meili. -

X : : in RE: HOLOCAUST VICTIM : Case No

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------X : : IN RE: HOLOCAUST VICTIM : Case No. CV-96-4849 ASSETS LITIGATION : (ERK)(MDG) (Consolidated : with CV-99-5161 and : CV-97-461) : -------------------------------------------------------: : MEMORANDUM & ORDER : This Document Relates to: All Cases : : : ------------------------------------------------------- X KORMAN, Chief Judge: On August 2, 2000, I approved the historic settlement in this case. See In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litig., 105 F. Supp. 2d 139 (E.D.N.Y. 2000). On July 26, 2001, when the Second Circuit affirmed my decision, the settlement became final. See In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litig., 14 Fed. Appx. 132 (2d Cir. 2001). Since then, we have distributed the following sums from the settlement fund: $150,589,699 to 1,934 claimants in the Deposited Assets Class in connection with 1,802 bank accounts found by the Claims Resolution Tribunal (“CRT”) to have belonged to victims of the Holocaust; $214,483,050 to 148,609 surviving members of the Slave Labor Class I; $45,000 to 45 members of the Slave Labor Class II; $7,804,050 to 2,898 surviving members of the Refugee Class; and $205,000,000 to needy survivors of the Holocaust through application of the cy pres doctrine to the Looted Assets Class. Indeed, we have succeeded on a great many fronts. What compels me to write is that over the past year-and-a-half, the bank defendants have filed a series of frivolous and offensive objections to the distribution process, and most recently to Special Master Judah Gribetz’s Interim Report on Distribution and Recommendation for Allocation of Excess 1 and Possible Unclaimed Residual Funds (hereafter “Interim Report”). -

Enemies of the People Third Print

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Sociology NEW SERIES 38 Enemies of the People Whistle-Blowing and the Sociology of Tragedy Magnus Haglunds ©Magnus Haglunds and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis , Stockholm 2009 ISSN 0491-0885 ISBN (978-91-86071-25-7) Printed in Sweden by US-AB Tryck & Media, Stockholm 2009 Distributor: eddy.se ab, Visby, Sweden Front cover image ©Gabriel Wentz. Based on the Attic figure “Dike beats Adikia with a hammer” "The motif of falling is a shorthand for tragedy, whereas tragedy is always about the question of whether failure is predetermined by fate, or whether failure is the result of human agency. It poses the question: Can you of your own free will work yourself into a situation with one inevitable outcome: to fall, to fail or to die?" Jan Verwoert on Bas Jan Ader Contents Preface ..........................................................................................................xi Acknowledgements.......................................................................................xv Abbreviations .............................................................................................. xvii Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................. 19 The Problem ................................................................................................................ 21 Enemies of the People................................................................................................. 24 Whistle-Blowing Research ..........................................................................................