X : : in RE: HOLOCAUST VICTIM : Case No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ii Main Part

UBS: Wealth Management BACHELOR THESIS (CASE STUDY) UBS: THE WAY TO BECOMING A GLOBAL PLAYER IN WEALTH MANAGEMENT "On which critical foundational factors are UBS and its leadership in Wealth Management built and with which major event is the current UBS crisis to be explained?" AUTHOR: ALAIN NTJAM OLTEN, AUGUST 9, 2013 SUPERVISOR: DR. KONDOVA GALIA INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT Alain Ntjam August 2013 1 UBS: Wealth Management Abstract Purpose: The objective of this bachelor thesis is to analyze in a case study manner, how the big Swiss bank UBS evolved and became a global player in wealth management. The guiding research question is: ‘On which critical foundational factors is UBS and its leadership in wealth management built, and with through which major event can the current UBS crisis be explained? Methodology and approach: The first analytical tool of this paper is the PEST analysis that aims to find out which environmental condition in the 1990s facilitated the UBS merger and how it came to the merger. The motives for its direction of growth will be analyzed to understand the bank's strategic intent in regards to wealth management and the bank's growth path. The next chapter seeks to understand the corporate ‘one firm strategy’ of UBS, how it relates to its organizational chart and which role the North American wealth management market plays within the organization. Further a comparison to Credit Suisse is made. The last chapter within the main part of the thesis attempts to sort out the significant activities of the value chain which creates or adds wealth management value for clients. -

Litigating the Holocaust: a Consistent Theory in Tort for the Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 27 Issue 3 Article 4 4-15-2000 Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations Derek Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Derek Brown Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations , 27 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (2000) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol27/iss3/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Litigating The Holocaust: A Consistent Theory in Tort For The Private Enforcement of Human Rights Violations I. INTRODUCTION Survivors of the Holocaust have repeatedly attempted, with little apparent success, to recover the assets their families deposited in Swiss banks prior to World War II. Considering the claimants' subsequent-yet understandable lack of documentation,- until now these survivors have had to rely solely on the banks' promises to expedite the return of these "dormant accounts" to their rightful owners.' Reliance on such promises, however, quickly evaporated with the public disclosure of one man's experience: Christoph Meili.4 A security guard for the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Meili became an international figure early in 1997. -

Holocaust Restitution Timeline

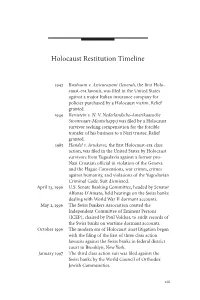

Holocaust Restitution Timeline 1942 Buxbaum v. Assicurazioni Generali, the first Holo- caust-era lawsuit, was filed in the United States against a major Italian insurance company for policies purchased by a Holocaust victim. Relief granted. 1949 Bernstein v. N. V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij was filed by a Holocaust survivor seeking compensation for the forcible transfer of his business to a Nazi trustee. Relief granted. 1985 Handel v. Artukovic, the first Holocaust-era class action, was filed in the United States by Holocaust survivors from Yugoslavia against a former pro- Nazi Croatian official in violation of the Geneva and the Hague Conventions, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and violations of the Yugoslavian Criminal Code. Suit dismissed. April 23, 1996 U.S. Senate Banking Committee, headed by Senator Alfonse D’Amato, held hearings on the Swiss banks dealing with World War II dormant accounts. May 2, 1996 The Swiss Bankers Association created the Independent Committee of Eminent Persons (ICEP), chaired by Paul Volcker, to audit records of the Swiss banks on wartime dormant accounts. October 1996 The modern era of Holocaust asset litigation began with the filing of the first of three class action lawsuits against the Swiss banks in federal district court in Brooklyn, New York. January 1997 The third class action suit was filed against the Swiss banks by the World Council of Orthodox Jewish Communities. xiii xiv Holocaust Restitution Timeline January 8, 1997 Christoph Meili discovered the Union Bank of Switzerland attempting to shred pre–World War II financial documents. March 25, 1997 French Prime Minister Alain Juppe created the Prime Minister’s Office Study Mission into the Looting of Jewish Assets in France (“Mattéoli Commission”) to study various forms of theft of Jewish property during World War II and the postwar efforts to remedy such theft. -

Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry Michael J

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 28 | Issue 3 Article 2 2002 Trading With The neE my: Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry Michael J. Bazyler Amber L. Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Michael J. Bazyler & Amber L. Fitzgerald, Trading With The Enemy: Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry, 28 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2003). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol28/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: BAZYLER Base Macro Final_2.doc Created on: 6/24/2003 12:17 PM Last Printed: 1/13/2004 2:22 PM TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: HOLOCAUST RESTITUTION, THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT, AND AMERICAN INDUSTRY Michael J. Bazyler∗ & Amber L. Fitzgerald∗∗ I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………685 II. THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES IN RESTITUTION EFFORTS ABROAD…………………………………………………………...686 A. Switzerland………...……………………………………….689 B. Germany..…………………………………………………...690 C. France......…………………………………………………...697 D. Austria………………..……………………………………..699 E. Israel……………………………...………………………….700 F. Insurance Claims…………………………………………..702 G. Art……………………………………………………………709 H. Role of Historical Commissions..………………………..712 1. Switzerland…………………………………………….712 a. Volcker Report……………………………………713 b. Bergier Final Report…………………………….715 2. Germany………………………………………………..719 3. Austria………………………………………………….720 4. France…………………………………………………..721 5. Other Countries……………………………………….723 ∗ Professor of Law, Whittier Law School, Costa Mesa, California; Fellow, Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (“USHMM”), Washington, D.C.; Research Fellow, Holocaust Educational Trust, London, England; J.D., University of Southern California, 1978; A.B., University of California, Los Angeles, 1974. -

Delegation Statements

Delegation Statements AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Statement by David A. Harris EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR To the Delegates to the Washington Conference on Holocaust- Era Assets: As one of the non-governmental organizations privileged to be accredited to the Conference, we join in expressing our hope that this historic gathering will fulfill the ambitious and worthy goals set for it. The effort to identify the compelling and complex issues of looted assets from the Second World War, and to consult on the most appropriate and expeditious means of addressing and resolving these issues, offers a beacon of light at the end of a very long and dark tunnel for Holocaust survivors, for the descendants of those who perished in the flames, for the vibrant Jewish communities which were destroyed, and for all who fell victim to the savagery and rapacity of those horrific times. We are pleased as well that, in addition to discussion of these enormously important topics, the Conference will also take up the matter of Holocaust education, for, in the end, this can be our permanent legacy to future generations. We hope that the Conference will reach a consensus on the need for enhanced international consultation, with the aim of encouraging more widespread teaching of the Holocaust in national school systems. Moreover, we commend those nations that have already taken impressive steps in this regard. Not only can teaching of the Holocaust provide young people with a better insight into the darkest chapter in this century's history, but, ultimately, it can serve to strengthen their commitment to fundamental principles of human decency, mutual understanding and tolerance – all of 146 WASHINGTON CONFERENCE ON HOLOCAUST-ERA ASSETS which are so necessary if we are to have any chance of creating a brighter future. -

NZZ On/I Ne.' English Window

.-."_.---~--- .._.._-----.=_:: .._-_ .. -'-_"J~ ~ NZZ on/i ne.' English Window 19.04.1998 InternationalNews I Editorialson WorldAffairsI Back~U11donWorldAffairsI NewsaboutS\\'itzedandI 5wisi bJWtr~ Weekin ReviO;'w I SWi56 StockMarketReportI SwissBusinessAbstractsI En;:lish Window Frontpagc . ;:go .'.' , ~ ~~ • ~,.." I r ~ '~." MootrecentBa~U11d I PreviousBac~d6 I. Dos~~~~1 h' I" . English Wsndow -.' .... " .. -. NZZ B.ckground on World Affairs February 1998 J News, , ....Ticker- -~-' - .-' ~......,..•.~, '. -, ,., NZZ-Archiv ~ The Sensation Hunter """. ' •• ,'~. , ~ ~.•• r .. ""..Service.'.'.-." ..~..I The Dubious Devices of Class-Action Attorney Edward Fagan r <";'.TAnzeigcn•.•. ' '" '" .',.7, Mail/Leserdiernt••. " .• ~•• N .•• '\, ..••• "_ •• ! byNikos Tzermias" Suchen I New York attorney Edward Fagan has attracted a great deal of attention.with his crass-action "Hitf~l~de~'"" " '"I suits against Swiss banks and againstl6 European insurance companies. But U.S. judges have ~~ '. ' -' •• '. _·f ,~.' ''''. NIZ-Sites I also warned him several times against "frivolous litigation" and family members of the victims of an airline crash have called him an "ambulance chaser." Ti~s<>';:;! For the past few months the World Trade Center, famous status symbol of American capitalism, has had a new tenant. The office on the 81st floor of one of the mighty Twin Towers at the southern tip of Manhattan seems to have some affinity with Switzerland. On the wall of the waiting room hang four clocks, showing the local time in Tokyo, New York, London ~d Zurich. But Suite 8101 does not house the branch office of some Swiss company. Lbdged' at that dizzying height is New York attorney Edward Fagan, who has instituted class-action lawsuits in the name of Holocaust survivors against Swiss banks and against 16 European insurance companies, and more recently filed charges of slander against the Union Bank of Switzerland on behalf of former Swiss bank security guard Christoph Meili and his wife Giuseppina. -

Swiss Historical Memory of World War II

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks @ The University of New Orleans University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Senior Honors Theses Undergraduate Showcase 12-2011 A Masterable Past? Swiss Historical Memory of World War II Sara Ormes University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ormes, Sara, "A Masterable Past? Swiss Historical Memory of World War II" (2011). Senior Honors Theses. 4. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses/4 This Honors Thesis-Unrestricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Honors Thesis-Unrestricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Honors Thesis-Unrestricted has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTERABLE PAST? SWISS HISTORICAL MEMORY OF WORLD WAR II An Honors Thesis Present to the Department of History of the University of New Orleans In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts, with University Honors and Honors in History by Sara Ormes December 2011 Acknowledgement I would like to thank a few people who have supported me in writing this Honors Thesis. -

The Holocaust Restitution Movement in Comparative Perspective

The Holocaust Restitution Movement in Comparative Perspective By Michael J. Bazyler* I. INTRODUCTION This article examines the use of civil litigation in the United States to deal with human rights abuses committed during World War II. The specific scena- rio examined is the Holocaust restitution movement in the United States, whose aim is to obtain financial restitution from European and American corporations 1 for their nefarious wartime activities. This article also examines other move- ments aiming to bring justice for historical wrongs that arose as a direct result of the successes achieved in the Holocaust restitution arena. Three such prominent movements are: (1) the lawsuits filed in the United States by victims of slave labor by Japan and Japanese industry during World War II; (2) the recent claims in U.S. courts of the survivors of Armenian genocide for reimbursement of the insurance proceeds paid by their deceased relatives; and (3) the emerging call for African-American reparations stemming from slavery. All of these move- ments are a direct outgrowth of the successful claims achieved in the Holocaust restitution arena. Finally, this article discusses the emerging debate about the propriety of seeking monetary damages for historical wrongs, especially as it has now emerged in the sphere of Holocaust-era litigation. The fact that American courts are being used today to deal with wrongs committed during World War II, over one-half century after the events took place, is astounding. In the history of American litigation, no class of cases has ever appeared in which so much time had passed between the wrongful act and the filing of the lawsuit. -

Chronology: Switzerland and the Second World War

Chronology: Switzerland and the Second World War Put together by the Parliamentary Services 1. Brief Survey 1934-1994 1934 Introduction of bank secrecy 1939- Second World War (for the chronology of events during this period, 45 refer to tables of events in the relevant literature) 1946 Federal Decree concerning the approval of the financial agreement concluded in Washington (the Washington Agreement, with message of the Federal Council, the Federal Decree, debates in the National Council and in the Council of States, and several newspaper articles) 1947 Short parliamentary question Meister: concerning valuable objects which might have found their way from Auschwitz to Switzerland 1949 Compensation Agreement of Switzerland with Poland (see also: Hug/Perrenoud Report, 1996) 1950 Compensation Agreement of Switzerland with Hungary (see also: Hug/Perrenoud Report, 1996) 1950 Interpellation of Werner Schmid. Heirless assets 1951 Short parliamentary question of Philipp Schmid 1957 Ludwig Report: Switzerland’s Refugee Policy from 1933 to the Present (1957) 1959 Motion by Huber. Assets of missing foreigners 1959 The Swiss Bankers Association argues against a registration decree on « heirless assets ». The assets without known beneficiary amount to only something like 900,000 francs. (information according to the NZZ- Fokus, Nr.2, Feb., 1997) 1962 Federal Decree on Assets situated in Switzerland belonging to Foreigners or Stateless Persons Persecuted for Reasons of Race, Religion, or Political Beliefs, approved on 20 December 1962 1962 The task -

Executive Summary

Case 1:96-cv-04849-ERK-JO Document 5040 Filed 03/28/19 Page 1 of 92 PageID #: 19256 In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation (Hon. Edward R. Korman) Final Report on the Swiss Banks Holocaust Settlement Distribution Process, Special Master Judah Gribetz and Deputy Special Master Shari C. Reig EXECUTIVE SUMMARY UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK X : Case No. CV 96-4849 (ERK)(MDG) : (Consolidated with CV 96-5161 and : CV 97-461) : : : IN RE: : HOLOCAUST VICTIM ASSETS : LITIGATION : : This Document Relates to: All Cases : : : X SPECIAL MASTERS’ FINAL REPORT ON THE SWISS BANKS HOLOCAUST SETTLEMENT DISTRIBUTION PROCESS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Judah Gribetz Special Master Shari C. Reig Deputy Special Master Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP 101 Park Avenue New York, New York 10178 March 28, 2019 DB3/ 201537552.1 Case 1:96-cv-04849-ERK-JO Document 5040 Filed 03/28/19 Page 2 of 92 PageID #: 19257 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 1 II. THE $1.25 BILLION SWISS BANKS HOLOCAUST SETTLEMENT .................... 2 III. THE BACKGROUND................................................................................................ 12 IV. SUMMARY OF DISTRIBUTION PROGRAMS ...................................................... 24 V. THE DISTRIBUTION PROGRAMS ......................................................................... 31 A. The Deposited Assets Class ............................................................................ 31 1. The -

Whistleblowing a Suitable Instrument to Improve Public Corporate Governance?

Whistleblowing A suitable instrument to improve public corporate governance? Albert E. Hofmeister 1. Background Academic as well as practitioner-oriented discussions have been dominated by concepts around economy, efficiency and effectiveness for many years. Whether or not this had a positive impact on the performance of the public sector as a whole is difficult to say, given the changing environment. Overall, the public ma- nagement reforms show a mixed balance: Clear «success stories» contrast with obvious failures. What is clear, though, is that performance is difficult to define and measure and that there is a clear preference for quantitative approaches, which are not always the most important ones. In addition, there might be a bias towards measuring primarily what puts an organisation in a good light, instead of what is important for the decision makers and the politicians setting the ob- jectives. Not only have the difficulties around performance measurement showed that successful reforms strongly depend on qualitative aspects and conditions. In this context, transparency is a key requirement. The lack of transparency was an im- portant driver behind a number of financial scandals, which occurred in past ye- ars. This has triggered a broad governance discussion, underpinning the impor- tance of ethical and moral aspects in economic activities. These aspects are key in order to ensure credibility and sustainability. Over the past years, this discus- sion has expanded its focus to the public sector. In this context, the call for transparency plays an important role. Actually, it is the job of the common management tools – «Controlling» and «Auditing» – to ensure the required level of transparency. -

The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action

Michigan Law Review Volume 102 Issue 6 2004 Justice for the Collective: The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action Paul R. Dubinsky New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Legal Remedies Commons Recommended Citation Paul R. Dubinsky, Justice for the Collective: The Limits of the Human Rights Class Action, 102 MICH. L. REV. 1152 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol102/iss6/9 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE FOR THE COLLECTIVE: THE LIMITS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS CLASS ACTION Paul R. Dubinsky* HOLOCAUST JUSTICE: THE BATTLE FOR RESTITUTION IN AMERICA'S COURTS. By Michael J. Bazyler. New York: New York University Press. 2003. Pp. xix, 411. Cloth, $34.95. IMPERFECT JUSTICE: LOOTED ASSETS, SLAVE LABOR, AND THE UNFINISHED BUSINESS OF WORLD wAR II. By Stuart E. Eizenstat. New York: Public Affairs. 2003. Pp. xi, 401. Cloth, $30. The class action lawsuit is our grand procedural experiment in collective justice. As against the U.S. legal system's strong orientation toward individual rights rather than group rights, the class action is a countercurrent. Through Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, large numbers of previously unaffiliated individuals can proceed in federal court as a group, litigating through representatives.