Part 3 Aids and Virus: from Film to Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Yimou Interviews Edited by Frances Gateward

ZHANG YIMOU INTERVIEWS EDITED BY FRANCES GATEWARD Discussing Red Sorghum JIAO XIONGPING/1988 Winning Winning Credit for My Grandpa Could you discuss how you chose the novel for Red Sorghum? I didn't know Mo Yan; I first read his novel, Red Sorghum, really liked it, and then gave him a phone call. Mo Yan suggested that we meet once. It was April and I was still filming Old Well, but I rushed to Shandong-I was tanned very dark then and went just wearing tattered clothes. I entered the courtyard early in the morning and shouted at the top of my voice, "Mo Yan! Mo Yan!" A door on the second floor suddenly opened and a head peered out: "Zhang Yimou?" I was dark then, having just come back from living in the countryside; Mo Yan took one look at me and immediately liked me-people have told me that he said Yimou wasn't too bad, that I was just like the work unit leader in his village. I later found out that this is his highest standard for judging people-when he says someone isn't too bad, that someone is just like this village work unit leader. Mo Yan's fiction exudes a supernatural quality "cobblestones are ice-cold, the air reeks of blood, and my grandma's voice reverberates over the sorghum fields." How was I to film this? There was no way I could shoot empty scenes of the sorghum fields, right? I said to Mo Yan, we can't skip any steps, so why don't you and Chen Jianyu first write a literary script. -

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

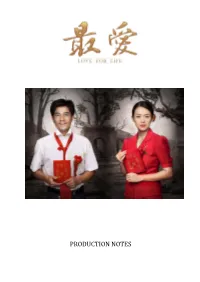

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

Film and the Chinese Medical Humanities

5 The fever with no name Genre-blending responses to the HIV-tainted blood scandal in 1990s China Marta Hanson Among the many responses to HIV/AIDS in modern China – medical, political, economic, sociological, national, and international – the cultural responses have been considerably powerful. In the past ten years, artists have written novels, produced documentaries, and even made a major feature-length film in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China.1 One of the best-known critical novelists in China today, Yan Lianke 阎连科 (b. 1958), wrote the novel Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦, copyright 2005; Hong Kong 2006; English translation 2009) as a scath- ing critique of how the Chinese government both contributed to and poorly han- dled the HIV/AIDS crisis in his native Henan province. He interviewed survivors, physicians, and even blood merchants who experienced first-hand the HIV/AIDS ‘tainted blood’ scandal in rural Henan of the 1990s giving the novel authenticity, depth, and heft. Although Yan chose a child-ghost narrator, the Dream is clearly a realistic novel. After signing a contract with Shanghai Arts Press he promised to donate 50,000 yuan of royalties to Xinzhuang village where he researched the AIDS epidemic in rural Henan, further blurring the fiction-reality line. The Chi- nese government censors responded by banning the Dream in Mainland China (Wang 2014: 151). Even before director Gu Changwei 顾长卫 (b. 1957) began making a feature film based on Yan’s banned book, he and his wife Jiang Wenli 蒋雯丽 (b. 1969) sought to work with ordinary people living with HIV/AIDS as part of the process of making the film. -

January 2019 ISSN 2048-0601 © British Association for Chinese Studies

Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies, Vol. 9 (1), January 2019 ISSN 2048-0601 © British Association for Chinese Studies Portrayals of the Chinese Être Particulières: Intellectual Women and Their Dilemmas in the Chinese Popular Context Since 2000 Meng Li The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Abstract This article studies the tension between post-Mao Chinese intellectual women and their dilemma in post-2000s Chinese popular media. TV dramas, films, songs and reality shows in which Chinese intellectual women and their dilemmas are identified, mis/represented, mis/understood and addressed are the research objects of this article. By foregrounding the two motifs of estrangement and escape in understanding and characterising post-Mao Chinese intellectual women, the article seeks to answer the following questions: In what ways are well-educated Chinese women consistently stigmatised under the unsympathetic limelight of the public? And for what reason are Chinese intellectual women identified as the être particulières in the popular context? Keywords: intellectual women, dilemma, estrangement, escape, popular cultural context. The article is partly developed from the postscript of my unpublished PhD thesis (Li, 2013). I thank my supervisors Professor Catherine Driscoll, Professor Yiyan Wang, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions to this article. 10 Meng Li Efforts to define the femininity of intellectual women and explain why intellectual women, “une être particulière” (Ernot, 1998: 102, cited in Long, 2013: 13), are exposed to stigmatisation has been the focus of my research of the previous decade. Both Luce Irigaray (1985) and Chen Ya-chen (2011) have proposed viewing female desire and language, as well as feminism itself, via a multi-dimensional lens. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Chinese Women’s Makeover Shows: Idealised Femininity, Self-presentation and Body Maintenance Xiaoyi Sun Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2014 1 Declaration This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: 2 Abstract Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Chinese television industry has witnessed the rise of a new form of television programme, Chinese Women’s Makeover Shows. These programmes have quickly become a great success and have received enormous attention from growing audiences. The shows are themed on educating and demonstrating to the audiences the information and methods needed to beautify their faces and bodies and consume products accordingly. -

2016 COB Release Genb8.Pages

2016 COB SCHEDULE Contents Los Angeles, UCLA Film & Television Archive | 1 Los Angeles, Film at REDCAT | 7 New York, Asia Society | 8 Washington, DC, National Gallery of Art | 10 Press Kit | 12 Presenting Partners & Sponsors | 13 Media Contact | 13 Los Angeles | UCLA Film & Television Archive THEATER KEY Wilder Billy Wilder Theater, courtyard level of the UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd. in Westwood Bridges James Bridges Theater, 1409 Melnitz Hall on the UCLA campus YRL Young Research Library on the UCLA campus Garden UCLA Sculpture Garden on the UCLA campus TICKETS $10 online; $9 general; $8 non-UCLA students, seniors, UCLA Alumni Association members (ID required) if purchased at the box office only. Free admission for UCLA students (current ID required); free tickets available on a first-come, first-served basis at the box office until 15 minutes before showtime, or the rush line afterwards. Online tickets available at www.cinema.ucla.edu/calendar. PARKING Wilder – Museum parking lot; enter from Westwood Blvd., just north of Wilshire. $6 flat rate after 6:00 pm weekdays and all day on weekends. Cash only. Bridges/YRL/Garden – UCLA Parking Structure 3; enter from Hilgard Ave. just south of Sunset Blvd. $12/ day or pay-by-space. INFORMATION | cinema.ucla.edu OPENING NIGHT Friday, October 14 • 7:30 PM @ Wilder West Coast Premiere THARLO र၎ China, 2015 Director/Screenwriter: Pema Tseden | DCP | Color | In Tibetan with English subtitles | 123 min. Cast: Shide Nyima, Yangshik Tso. !1 Tibetan sheep-herder Tharlo journeys from his remote village to get a photo ID in the nearest town of Qinghai province where he meets a city woman whose romantic intentions may not be what they first seem. -

21St Century Chinese Cinema in the Late 1960S and 70S, Red Ballets and Operas Dominated the Chinese Screen

21st century Chinese cinema In the late 1960s and 70s, red ballets and operas dominated the Chinese screen. Mao died in 1976: a new age of cinema emerged with the founding of the Beijing Film Academy in 1978. Expressing new confidence in both historical and contemporary themes, young film-makers like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige brought Chinese film to a global audience with masterpieces such as Red Sorghum (1987) and Farewell my Concubine (1993). Martin Scorsese named Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief (1986) as his favourite film of the 1990s (when it was released in the US). But many of these films encountered stigma at home. Growing commercialisation and globalisation since the 1980s and 90s have driven Chinese cinema to explore new modes of both cinematography and moneymaking, leading to exploratory films at home in Western arthouse cinemas, and entertaining movies that have drawn huge crowds in China. In this modest selection, we set the scene with a film that shaped the vision of China’s 21st century filmmakers. Tian Zhuangzhuang’s restrained criticism of 1950s and 60s state policies in The Blue Kite (1992) led to his blacklisting by the Party, but did not preclude him for mentoring the next generation of filmmakers. We then showcase a selection of remarkable 21st century films that have won world-wide acclaim for China’s talented directors and actors. Our selection finishes with a couple of rollicking tales that have attracted the popular domestic audience: a grand epic: Red Cliff (2008), known better for its cavalry charges than its character development, and Lost in Thailand (2012) that, airily suspending social comment and political tension, was the biggest ever box office success in China. -

Huanxi Media Signs Renowned Chinese Director Wang Xiaoshuai

[Immediate Release] Huanxi Media Signs Renowned Chinese Director Wang Xiaoshuai (Hong Kong, 24 February 2017) – Huanxi Media Group Limited (“Huanxi Media” or “the Group;” stock code: 1003) is pleased to announce that it has signed a cooperation agreement with prominent Chinese film director, Wang Xiaoshuai and Dongchun Films Co., Limited. Huanxi Media acquires priority investment rights in two productions (comprising film and internet series) directed or produced by Wang Xiaoshuai (“new productions”) in the coming six years, and also obtains global priority rights to distribute the new productions, and global exclusive distribution and resale rights on new media platform. As a pioneer in Chinese independent film and a chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres appointed by the French Minister of Culture, Wang Xiaoshuai has directed 11 films and has been nominated 8 times in the “Big Three” international film festivals. His directorial debut, The Days, was included in the collection by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and was recognized as one of the most significant and preliminary Chinese independent films. His representative work, Beijing Bicycle, won the Grand Jury Silver Bear Award at the 2001 Berlin International Film Festival; his other work, In Love We Trust, won the Silver Bear Award for the best screenplay in Berlin International Film Festival; another masterpiece, Shanghai Dreams, won the Jury Prize at the 58th Cannes Film Festival. - End - Page 1 Huanxi Media Group Limited (stock code: 1003) Signs Renowned Chinese Director Wang Xiaoshuai 24 February 2017 Profile of Director Director Wang Xiaoshuai Wang Xiaoshuai, born in 1966, is a film director and producer in China. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform EFM 2011 tm BERLIN POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OF FILM GUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSConnect to Seller - Buy Product EFM 2011 Bumper Online - EFM Daily Editions - Unabridged EFM Product Guide + Stills The Visual is The Medium synopsisandtrailers.com makes it easy for you to Your Simplest Sales Tool read-watch-connect-buy like never before. S HOWCASING T RAILERS D AILY F EB 10-16 An end to site hopping. VISIT:thebusinessoffilmdaily.com For Buyers: Time is Money - View & Connect For Sellers: Attract Buyer Interest - Spend Your Time Promoting New Films November 2 - 9, 2011 Arrow Entertainment Sahamongkolfilm MGB Stand #120 MGB Stand #129 Vision Films Imageworks Ent. MGB Booth #127 Maritim Hotel Suite 9002 STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE BERLIN PRODUCT GUIDE 2011 Writer: Laura Beccaria 6 SALES Producer: Abano Producion, Anera Films, 6 Sales, Alto de las cabañas 5 28231 Las Continental Producciones Rozas de Madrid. Tel: +34.91.636.10.54. Delivery Status: completed Fax: +34.91.710.35.93. www.6sales.es, E- Year of Production: 2010, Country of mail: [email protected] Origin: Spain Sales Agent Little MUMU’s journey towards her ulti- At EFM: Marina Fuentes (Partner), mate dream: to become a great star. Avraham Pirchi (Partner), Mar Abadin THE RUNWAY (Head of Sales) http://www.6sales.es/theRunaway.html Office: Washington Suite, office 100, Family comedy (100 min) Marriott Hotel, Tel: +49(0)30.22000.1127 -

UCL China Centre for Health and Humanity, MEDICAL and HEALTH HUMANITIES FILM LIST Updated 6 August 2016

UCL China Centre for Health and Humanity, MEDICAL AND HEALTH HUMANITIES FILM LIST Updated 6 August 2016 Title, Title, Pinyin Title, Director Date Studio Region Notes pinyin Chinese with tones translations characters A mian B A 面 B 面 A miàn B Side A Side Ning Ying 宁瀛 2010 PRC mian miàn B; The (Níng Yíng) Double Life Bawang 霸王别姬 Bàwáng Farewell My Chen Kaige 陈 2003 Mainlan bieji bié jī Concubine 凯歌 (Chén d Kǎigē) China/H ong Kong Chunguang 春光乍泄 Chūnguāng Happy Wong Kar Wai 1997 Hong Christopher Doyle zha xie zhà xiè Together 王家卫 (Wáng Kong/Ar cinematographer Jiāwèi) gentina Chunmiao 春苗 Chūn miáo Chunmiao; Xie Jin 谢晋 1975 PRC Spring (Xiè Jìn), Seedlings Yan Bili 颜碧丽 (Yán Bìlì), Liang Tingduo 梁廷铎 (Liáng Tíngduó) 1 Dagong 打工老板 Dǎgōng Factory Boss Zhang Wei 张 2014 PRC laoban Zhang Wei lǎobǎn 唯 (Zhāng Wéi) Donggong 东宫西宫 Dōnggōng East Palace, Zhang Yuan 张 1996 PRC xigong xīgōng West Palace; 元 (Zhāng Behind the Yuán) Forbidden City Erzi 儿子 Érzi Sons Zhang Yuan 张 2006 PRC 元 (Zhāng Yuán) Feiyue 飞越老人院 Fēiyuè Full Circle Zhang Yang 张 2011 PRC laorenyuan lǎorén 扬 (Zhāng yuàn Yáng) Fenshiren 焚尸人 Fénshīrén The Peng Tao 彭韬 2012 PRC Cremator (Péng Tāo) Feng ai 疯爱 Fēng ài ’Til madness Wang Bing 王 2013 Japan/F Documentary. do us part; 兵 (Wáng Bīng) rance/H On the inhumane, Till madness ong frightening and do us part Kong humiliating living conditions of mental patients in Chinese mental institutions. Fuzi qing 父子情 Fùzǐ qíng Father and Fang Yuping 1981 Hong Son 方育平 (Fāng Kong Yùpíng) (Allen Fong) 2 Gang de 钢的琴 Gāng de Piano in a Zhang Meng 2010 PRC qin qín