This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

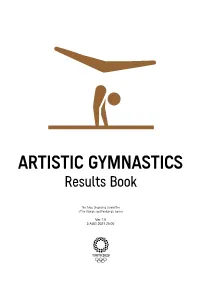

Results Team + Mixed

Ariake Gymnastics Centre Artistic Gymnastics 有明体操競技場 体操競技 / Gymnastique artistique Centre de gymnastique d'Ariake Men 男子 / Hommes SAT 24 JUL 2021 Qualification 予選 / Qualification Results 結果 / Résultats NOC A-A Rank Bib Total Name Rank V1 V2 Avg. 1 JPN - Japan 146 HASHIMOTO Daiki 14.700 14.766 13.866 14.866 15.300 15.033 88.531 (1) 148 KAYA Kazuma 13.933 14.833 14.366 13.200 15.100 14.033 85.465 (9) 149 KITAZONO Takeru 14.666 13.916 13.333 14.700 14.900 14.433 85.948 (7) 150 TANIGAWA Wataru 14.466 13.833 14.300 13.666 DNS DNF 15.241 13.400 84.906 (13) Total 43.832 (2) 43.515 (3) 42.532 (2) 43.232 (5) 45.641 (2) 43.499 (1) 262.251 Q 2 CHN - People's Republic of China 113 LIN Chaopan 13.966 14.100 13.433 14.666 14.733 14.200 85.098 (12) 115 SUN Wei 14.333 14.833 14.233 14.766 15.133 14.000 87.298 (4) 116 XIAO Ruoteng 14.866 14.300 14.200 14.700 15.400 14.266 87.732 (3) 118 ZOU Jingyuan DNS 14.600 DNS DNS 16.166 DNS DNF Total 43.165 (4) 43.733 (1) 41.866 (4) 44.132 (2) 46.699 (1) 42.466 (3) 262.061 Q 3 ROC - ROC 168 ABLIAZIN Denis 14.300 DNS 14.800 14.900 14.566 14.733 DNS DNS DNF 169 BELYAVSKIY David 12.933 14.733 14.000 14.300 15.325 14.033 85.324 (10) 170 DALALOYAN Artur 13.700 13.800 14.500 14.658 DNS DNF 15.233 14.066 85.957 (6) 172 NAGORNYY Nikita 15.066 14.366 14.333 14.700 14.866 14.783 14.966 14.466 87.897 (2) Total 43.066 (5) 42.899 (4) 43.633 (1) 44.258 (1) 45.524 (3) 42.565 (2) 261.945 Q 4 USA - United States of America 191 MALONE Brody 13.666 13.733 14.200 14.533 14.633 14.533 85.298 (11) 192 MIKULAK Samuel 14.466 13.900 13.866 -

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

Deconstructing the Children's Culture Industry

DECONSTRUCTING THE CHILDREN‘S CULTURE INDUSTRY: A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS FROM YOUNG PEOPLE by JENNIFER ANN HILL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) (Social Work, Sociology, Psychology,) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) April 2013 © Jennifer Ann Hill, 2013 ABSTRACT The children‘s ―culture industry,‖ meaning the mass production of popular culture by corporations, has systematically targeted children to persuade them to desire commodities while promising an increase in happiness. Media in all forms has become the conduit through which corporations have access to children and the means by which they influence, mould and profoundly impact children's lives. Indeed, consumer culture plays a dominant role for individuals living in such cultures, arguably more than any other institution including government. In the 1990s, the most intense commercial campaign in the history of childhood had commenced. Despite the pervasiveness of consumerism, there has been a notable gap in the literature to ascertain from young people, in their own words, what are the experiences of and meanings attributed to consumerism throughout their childhoods. Using a paradigm of qualitative research, the present dissertation provides a detailed description of how young people, those aged 18 or 19, perceive the presence of consumer culture in their lives, both presently and with particular focus on the past, as children. Data presented here suggest that most of the young people interviewed feel considerable pressure to conform to the standards of consumerism, including the adoption of brand culture, fads and a ‗buy-and-consume‘ modality. -

Ver.1.0 3 AUG 2021 20:00 Version History

Ver.1.0 3 AUG 2021 20:00 Version History Version Date Created by Comments Erick 1.0 31 JUL 2021 First Version ZUCHINI Table of Contents Competition Format and Rules Medallists by Event Medal Standings Gymnastics Medal Standings Multi-Medallists at these Games Competition Schedule Men Entry List by NOC Competition Officials Men’s Qualification Start List Judges Assignments Results (Qualification) Results (Team) Results (All-Around) Results (Floor Exercise) Results (Pommel Horse) Results (Rings) Results (Vault) Results (Parallel Bars) Results (Horizontal Bar) Tie Break Report (Floor Exercise) Tie Break Report (Pommel Horse) Tie Break Report (Rings) Tie Break Report (Vault) Tie Break Report (Parallel Bars) Tie Break Report (Horizontal Bar) Men's Team Final Medallists Start List Judges Assignments Results Men's All-Around Final Medallists Start List Judges Assignments Results Men's Apparatus Final Medallists (Floor Exercise) Medallists (Pommel Horse) Medallists (Rings) Medallists (Vault) Medallists (Parallel Bars) Medallists (Horizontal Bar) Start List (Day 1 of 3) Start List (Day 2 of 3) Start List (Day 3 of 3) Judges Assignments (Day 1 of 3) Judges Assignments (Day 2 of 3) Judges Assignments (Day 3 of 3) Results (Floor Exercise) Results (Pommel Horse) Results (Rings) Results (Vault) Results (Parallel Bars) Results (Horizontal Bar) Tie Break Report (Floor Exercise) Tie Break Report (Vault) Women Entry List by NOC Competition Officials Women's Qualification Start List Judges Assignments Results (Qualification) Results (Team) Results (All-Around) -

Indian Gymnast

indian gymnast Volume.24 No. 1 January.2016 DIPA KARMAKAR DURING WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS, FIRST INDIAN WOMAN GYMNAST TO QUALIFY FOR THE APPARATUS FINAL COMPETITION IN VAULT IN THE 46th WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS A BI-ANNUAL GYMNASTICS PUBLICATION INDIAN GYMNASTICS CONTINGENT IN GLASGOW (SCOTLAND) FOR PARTICIPATION IN THE 46TH WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS HELD FROM 23rd OCT. to 1st NOV. 2015 Dr. G.S.Bawa with Jordan Jovtchev, the Olympic Silver Medalist and World Champion(4 Gold, 5 Silver and 4 Bronze medals) who participated in 6 Consecutive Olympic Games and presently he is President of Bulgarian Gymnastics Federation Indian Gymnast – A Bi-annual Gymnastics Publication Volume 24 Number 1 January, 2016 - 1 CONTENTS Page Editorial 2 New Elements in MAG Recognized by the FIG 3 by: Steve BUTCHER, President of the Men’s Technical Committee, FIG Rehabilitation for Ankle Sprain 10 by: Ryan Harber, LAT, ATC, CSCS Technique and Methodic of Stalder on Uneven Bars. 15 [by: Dr. Kalpana Debnath. Chief Gymnastics Coach, SAI NS NIS Patiala [ 17 History of Development of Floor Exercises by: Prof. Istvan Karacsony, Hungary th 21 Some Salient Features of 46 Artistic World Gymnastics Championships: by: Dr. Gurdial Singh Bawa, Chief National Coach 54th All India Inter University Gymnastics Championships (MAG, WAG, RG ) 32 organised by Punjabi University Patiala,from 7th to 11th January, 2015 by Dr. Raj Kumar Sharma, Director Sports, Punjabi University,Patiala Results of 46th Artistic World Gymnastics Championships, held at Glasgow, 37 Scotland , from 23rd Oct. to 1st Nov., 2015 by Dr. Kalpana Debnath. Chief Gymnastics Coach, SAI NS NIS Patiala 34th Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championships in Stuttgart (GER) , from 7th 39 to 13th September, 2015. -

TV Show Knows What's in Your Fridge Is Food for Thought

16 | Wednesday, June 17, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY YOUTH ometimes you have to travel didn’t enjoy traditional Chinese to appreciate your own. music that much until he pursued his Sometimes, waking up in a music studies in the United States. foreign land gives you a pre- When leaving China, he took with Scious insight into your own country. him the hulusi, a kind of Chinese Fang Songping is a musician and wind instrument made from a has traveled but when he was at gourd, and played it recreationally home with his pipa-player father, in the college. The exotic sound of Fang Jinlong, he preferred Western the instrument won him lots of fans rock. and requests to perform on stage. It was hulusi, the gourd-like Then he started researching about instrument, that really changed his traditional Chinese music and com- life. He happened to bring it to Los bining elements of it into his own Angeles, while studying music there. compositions. In 2015, he returned His classmates were fascinated to China and started his career as an when he played music with it, and a indie musician. new horizon opened up before him. Now, Fang Songping works as the According to a recent report on music director of a popular reality traditional Chinese music, young show, Gems of Chinese Poetry, Chinese people are turning their which centers on traditional Chi- attention to traditional arts. More nese arts, such as poetry, music, and more are listening to traditional dance and paintings. He composed Chinese music. eight original instrumental pieces, The report was released on June inspired by traditional Chinese cul- 2, under the guidance of the China ture, like music, chess, calligraphy Association of Performing Arts, by and paintings. -

Rob Checks His List Twice

The Undergraduate Magazine Vol. V, No. 10 | January 24, 2005 House of Pain Turn Over for Sex Cosmetic Conformity My Old Friend John Lauren laments the onerous housing Thuy and Roz double up on your Anna predicts the downfall of mankind James provides a trio of reviews to application favorite subject one surgery at a time guide your listening pleasure Page 3 Page 8 Page 5 Page 7 YOU’RE NEXT, BITCH MARIAN LEE MID SEASON REPORT CARD CUDDLE ’N’ Rob checks his list twice COLLAGE ANDREW PEDERSON | BRUT FORCE ROB FORMAN | MY 13-INCH BOX WHEN I LEFT PHILADELPHIA EVERY SO OFTEN I find Desperate Housewives: Clearly the shock of the season. for Winter Break, I was hoping for myself questioning whether For some unprecedented reason—read a sense of humor— a pleasant change in climate. At I am, in fact, in a waking Desperate Housewives has managed to gain critical acclaim home in Nevada, winter usually dream. You see, I have an while being a primetime soap-opera. The witty women on means something like forty five de- acquired taste. You might Wisteria Lane have already won a Golden Globe for Best grees, 20% humidity and clear skies. even call it obscure, cultist, Comedy Series, and Teri Hatcher won for Best Lead Actress This time, however, the weather and unpopular. After all, I in a Comedy Series. Oh, and the show is the biggest new gods granted me only one week of trumpeted my love of Angel show of the season, and second overall only to the original sweet, gentle desert winter before and Wonderfalls last year CSI. -

Departamento De Direito Regulação Da Mídia

0 PUC DEPARTAMENTO DE DIREITO REGULAÇÃO DA MÍDIA E LIBERDADE DE EXPRESSÃO: UMA ANÁLISE DA EXPERIÊNCIA ALEMÃ E AUSTRALIANA por CAROLINA MONTEIRO DE CASTRO SILVEIRA ORIENTADOR: FÁBIO CARVALHO LEITE 2016.2 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO RUA MARQUÊS DE SÃO VICENTE, 225 - CEP 22453-900 RIO DE JANEIRO - BRASIL 1 REGULAÇÃO DA MÍDIA E LIBERDADE DE EXPRESSÃO: UMA ANÁLISE DA EXPERIÊNCIA ALEMÃ E AUSTRALIANA por CAROLINA MONTEIRO DE CASTRO SILVEIRA Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de Direito da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) para a obtenção do Título de Bacharel em Direito. Orientador(a): Fábio Carvalho Leite 2 Agradecimentos Agradeço ao meu orientador Prof. Fábio Carvalho Leite pelo incentivo e presteza no auxílio às atividades, pelos anos de PIBIC, pelas reuniões, pelos conselhos e correções que muito me fizeram crescer e aprender. Os seus ensinamentos foram fundamentais na elaboração deste trabalho. Agradeço aos demais professores da PUC-Rio, que foram corresponsáveis por todo o aprimoramento intelectual que a faculdade de direito proporcionou. O corpo docente possibilitou muitas visões além dos livros, muitas inspirações e reflexões que tornaram a graduação completa. À PUC-Rio, que proporcionou estrutura e profissionais fantásticos, sem os quais a graduação não teria sido tão excepcional. Intercâmbios, experiências e prêmios que a PUC-Rio me concedeu e que formaram o que sou hoje. Agradeço também à Vice-Reitoria Comunitária pela bolsa de estudos, que possibilitou que eu me formasse nesta instituição de ensino excelente. À Patrícia Spínola e Thiago Spínola, que forneceram o endereço na Austrália, sem o qual jamais poderíamos ter realizado o experimento com a autoridade reguladora da mídia australiana. -

Appendix a – Transcripts of Finale Show of American Idol 2005 103

A CRITICAL COMPARISON OF AMERICAN IDOL AND SUPER GIRL: A CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION ANALYSIS OF AMERICAN AND CHINESE CULTURES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY YUNXUE DING ADVISOR: DR. JAMES W. CHESEBRO BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2008 2 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 List of Tables 3 Acknowledgements 4 Chapter One: Introduction 5 Chapter Two: Review of the Literature 19 Chapter Three: Methods 37 Chapter Four: Findings 55 Chapter Five: Major Conclusions and Limitations 83 References: 93 Appendix A – Transcripts of Finale Show of American Idol 2005 103 Appendix B – Transcripts of Finale Show of Super Girl 2005 118 Appendix C – Top-level meetings and contacts between the United States and China since 1972 157 Appendix D – Thirteen core value dimensions used to distinguish world cultures 160 3 List of Tables Table 1 – Rankings of American Idol Finale shows 33 Table 2 – Fantasy theme analysis: basic components, definitions, and critical concepts/notes on method. 49 Table 3 – The awards and nominations that Ms. Carrie Underwood won 57 Table 4 – Votes of 3 finalists in Finale Show of Super Girl season 2005 59 4 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my appreciation to Dr. James W. Chesebro for his guidance towards the completion of this thesis and confidence in me. I am also grateful to Dr. Joseph P. Misiewicz and Dr. John Dailey for their constructive criticism in the writing of this thesis. I would also like to thank my wife, Xuesong Shen, for her unconditional love and continuous support. -

Film and the Chinese Medical Humanities

5 The fever with no name Genre-blending responses to the HIV-tainted blood scandal in 1990s China Marta Hanson Among the many responses to HIV/AIDS in modern China – medical, political, economic, sociological, national, and international – the cultural responses have been considerably powerful. In the past ten years, artists have written novels, produced documentaries, and even made a major feature-length film in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China.1 One of the best-known critical novelists in China today, Yan Lianke 阎连科 (b. 1958), wrote the novel Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦, copyright 2005; Hong Kong 2006; English translation 2009) as a scath- ing critique of how the Chinese government both contributed to and poorly han- dled the HIV/AIDS crisis in his native Henan province. He interviewed survivors, physicians, and even blood merchants who experienced first-hand the HIV/AIDS ‘tainted blood’ scandal in rural Henan of the 1990s giving the novel authenticity, depth, and heft. Although Yan chose a child-ghost narrator, the Dream is clearly a realistic novel. After signing a contract with Shanghai Arts Press he promised to donate 50,000 yuan of royalties to Xinzhuang village where he researched the AIDS epidemic in rural Henan, further blurring the fiction-reality line. The Chi- nese government censors responded by banning the Dream in Mainland China (Wang 2014: 151). Even before director Gu Changwei 顾长卫 (b. 1957) began making a feature film based on Yan’s banned book, he and his wife Jiang Wenli 蒋雯丽 (b. 1969) sought to work with ordinary people living with HIV/AIDS as part of the process of making the film. -

2016 China Overview – TV

TV © 2016 Beyond Summits 2 Summary: • TV media market has tended to be saturated with almost 99% coverage rate in 10 years. However, Chinese are losing their interests in watching TV. The average age of real TV audience is getting older. The biggest proportion of TV audience is constituted by audience aged over 45 years old. The older TV audience are more likely to be heavy TV users. • In terms of TV programs, Chinese TV content is mainly produced by CCTV and provincial satellite TVs. However, TV production and broadcasting will further separate in the future, and high-quality content will be incline to broadcast through Internet platforms. Eventually, the number of TV audience will decrease. More people will choose to watch videos online instead of on TV. • Since 2014, the advertising on TV has seen a dropping trend. In the first half of 2015, TV ads even showed a negative increase. CCTV and provincial satellite TVs were still two major platforms for business to place ads into. © 2016 Beyond Summits 3 Summary: • In 2015,TV programs were mainly broadcasting about TV series, news and various shows,accounting for 57.1% of all programs. The top five provincial TV channels swept most high-rating programs. • The watching length of TV variety shows had a significant increase in 2015. Hunan Sat-TV variety shows' average rating was the highest in 2015. With the rapid development of variety shows and IP TV dramas, a rising trend of title sponsorship and ads were seen in 2015. • What users watch on TV is quite similar with what they watch online.