Is Evolution Evil?: a Celebration of the Cult of Formlessness by Daniel Mckernan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deconstructing the Children's Culture Industry

DECONSTRUCTING THE CHILDREN‘S CULTURE INDUSTRY: A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS FROM YOUNG PEOPLE by JENNIFER ANN HILL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) (Social Work, Sociology, Psychology,) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) April 2013 © Jennifer Ann Hill, 2013 ABSTRACT The children‘s ―culture industry,‖ meaning the mass production of popular culture by corporations, has systematically targeted children to persuade them to desire commodities while promising an increase in happiness. Media in all forms has become the conduit through which corporations have access to children and the means by which they influence, mould and profoundly impact children's lives. Indeed, consumer culture plays a dominant role for individuals living in such cultures, arguably more than any other institution including government. In the 1990s, the most intense commercial campaign in the history of childhood had commenced. Despite the pervasiveness of consumerism, there has been a notable gap in the literature to ascertain from young people, in their own words, what are the experiences of and meanings attributed to consumerism throughout their childhoods. Using a paradigm of qualitative research, the present dissertation provides a detailed description of how young people, those aged 18 or 19, perceive the presence of consumer culture in their lives, both presently and with particular focus on the past, as children. Data presented here suggest that most of the young people interviewed feel considerable pressure to conform to the standards of consumerism, including the adoption of brand culture, fads and a ‗buy-and-consume‘ modality. -

Quest Volume 16 Issue 21

MODEST TURNOUT, MIXED MESSAGES FOR MADISON EQUALITY MARCH Madison - Sunny skies and brisk 20 degree tem - peratures greeted a crowd estimated between 100 to 200 marching for LGBT equality and more here December 5. Inspired by the National Equality March last October, Unified For Equality (UFE), a coalition of Madison and southern Wisconsin LGBT groups, organized the march and rally on the Capitol steps as a local follow-up to the Washington DC event. And, as often happens in coalition building, mes - sages at the rally became mixed. Quest correspondent Steve Vargas pegged the total at a little over one hundred, while rally organizers offered a more optimistic estimate of about 200. The march also briefly interrupted a Fair Wisconsin board of directors meeting when it passed the statewide organization’s State Street offices shortly after Noon. One board member told Quest the marchers “num - bered about 120.” In addition to calling attention to the recent Wis - consin Supreme Court hearing of McConkey lawsuit challenging that validity of the 2006 “Marriage Pro - tection” Amendment referendum, the rally’s focus Madison; OutReach/OutThere of Madison; P.E.A.C.E. Amendment and an executive order to overturn the expanded to include speakers advocating universal at UW-Whitewater and others. Organizers made “Don’t-Ask-Don’t-Tell” policy for military personnel. health care and protesting the ongoing wars in Iraq heavy use of email text and the social networking According to the UFE press release that announced and Afghanistan - especially President Obama’s De - site Facebook to promote the event. UFE spokesper - the march, the LGBT community “lacks everyday cember 1 decision to add 30,000 troops to the lat - son Jessie Otradovec reported that she was happy rights in addition to the marriage right and refuses ter battle theater. -

Rob Checks His List Twice

The Undergraduate Magazine Vol. V, No. 10 | January 24, 2005 House of Pain Turn Over for Sex Cosmetic Conformity My Old Friend John Lauren laments the onerous housing Thuy and Roz double up on your Anna predicts the downfall of mankind James provides a trio of reviews to application favorite subject one surgery at a time guide your listening pleasure Page 3 Page 8 Page 5 Page 7 YOU’RE NEXT, BITCH MARIAN LEE MID SEASON REPORT CARD CUDDLE ’N’ Rob checks his list twice COLLAGE ANDREW PEDERSON | BRUT FORCE ROB FORMAN | MY 13-INCH BOX WHEN I LEFT PHILADELPHIA EVERY SO OFTEN I find Desperate Housewives: Clearly the shock of the season. for Winter Break, I was hoping for myself questioning whether For some unprecedented reason—read a sense of humor— a pleasant change in climate. At I am, in fact, in a waking Desperate Housewives has managed to gain critical acclaim home in Nevada, winter usually dream. You see, I have an while being a primetime soap-opera. The witty women on means something like forty five de- acquired taste. You might Wisteria Lane have already won a Golden Globe for Best grees, 20% humidity and clear skies. even call it obscure, cultist, Comedy Series, and Teri Hatcher won for Best Lead Actress This time, however, the weather and unpopular. After all, I in a Comedy Series. Oh, and the show is the biggest new gods granted me only one week of trumpeted my love of Angel show of the season, and second overall only to the original sweet, gentle desert winter before and Wonderfalls last year CSI. -

Departamento De Direito Regulação Da Mídia

0 PUC DEPARTAMENTO DE DIREITO REGULAÇÃO DA MÍDIA E LIBERDADE DE EXPRESSÃO: UMA ANÁLISE DA EXPERIÊNCIA ALEMÃ E AUSTRALIANA por CAROLINA MONTEIRO DE CASTRO SILVEIRA ORIENTADOR: FÁBIO CARVALHO LEITE 2016.2 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO RUA MARQUÊS DE SÃO VICENTE, 225 - CEP 22453-900 RIO DE JANEIRO - BRASIL 1 REGULAÇÃO DA MÍDIA E LIBERDADE DE EXPRESSÃO: UMA ANÁLISE DA EXPERIÊNCIA ALEMÃ E AUSTRALIANA por CAROLINA MONTEIRO DE CASTRO SILVEIRA Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de Direito da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) para a obtenção do Título de Bacharel em Direito. Orientador(a): Fábio Carvalho Leite 2 Agradecimentos Agradeço ao meu orientador Prof. Fábio Carvalho Leite pelo incentivo e presteza no auxílio às atividades, pelos anos de PIBIC, pelas reuniões, pelos conselhos e correções que muito me fizeram crescer e aprender. Os seus ensinamentos foram fundamentais na elaboração deste trabalho. Agradeço aos demais professores da PUC-Rio, que foram corresponsáveis por todo o aprimoramento intelectual que a faculdade de direito proporcionou. O corpo docente possibilitou muitas visões além dos livros, muitas inspirações e reflexões que tornaram a graduação completa. À PUC-Rio, que proporcionou estrutura e profissionais fantásticos, sem os quais a graduação não teria sido tão excepcional. Intercâmbios, experiências e prêmios que a PUC-Rio me concedeu e que formaram o que sou hoje. Agradeço também à Vice-Reitoria Comunitária pela bolsa de estudos, que possibilitou que eu me formasse nesta instituição de ensino excelente. À Patrícia Spínola e Thiago Spínola, que forneceram o endereço na Austrália, sem o qual jamais poderíamos ter realizado o experimento com a autoridade reguladora da mídia australiana. -

Reality Television and Its Impact on Women's Body Image Ayarza Manwaring Eastern Kentucky University, Ayarza [email protected]

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2011 Reality television and its impact on women's body image Ayarza Manwaring Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Manwaring, Ayarza, "Reality television and its impact on women's body image" (2011). Online Theses and Dissertations. 50. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/50 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REALITY TELEVISION AND ITS IMPACT ON WOMEN‟S BODY IMAGE By AYARZA MANWARING Bachelor of Science Smith College Northampton, MA 2008 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2011 Copyright © Ayarza Manwaring, 2011 All rights reserved ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my mom Daphne Manwaring Who taught me to find joy in reading iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Matthew Winslow, for allowing me to learn about research at my own pace. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee for agreeing to take the time to assist me with this project. I would also like to thank the members of the general psychology program, Nannan Li, Lakita Johnson, Jonathan Ritter, Lynn Thompson and Christopher Palmer, who provided me with an outlet to vent my frustrations. -

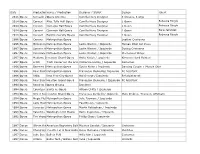

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

MTV Smut Peddlers

TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 1 Major Findings¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 1 I. Background¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 2 II. Study Parameters & Methodology¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 3 III. Overview of Major Findings¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 3 ◊ Other Findings¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 3 IV Examples:¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 4 ◊ Foul language o On reality shows¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 4 o In music videos¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 4 ◊ Sex o On reality shows¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 5 o In music videos¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 6 ◊ Violence o On reality shows¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 9 o In music videos¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 10 V. Conclusion¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 10 End Notes¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 11 The Parents Television Council¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 12 Entertainment Tracking Systems: State-of-the-Art Television Monitoring System¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 13 Acknowledgements¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤¤ Page 14 MTV Smut Peddlers 3,056 depictions of sex or various forms of nudity and MTV Smut Peddlers: 2,881 verbal sexual references. -

'Just Like Us'?

‘Just like us’? Investigating how LGBTQ Australians read celebrity media Lucy Watson A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. A version of Chapter Nine appears in the book Gender and Australian Celebrity Culture (forthcoming), edited by Anthea Taylor and Joanna McIntyre. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Lucy Watson 25th September 2019 i Abstract In the 21st century, celebrity culture is increasingly pervasive. Existing research on how people (particularly women) read celebrity indicates that celebrity media is consumed for pleasure, as a way to engage in ‘safe’ gossip amongst imagined, as well as real, communities about standards of morality, and as a way to understand and debate social and cultural behavioural standards. The celebrities we read about engage us in a process of cultural identity formation, as we identify and disidentify with those whom we consume. Celebrities are, as the adage goes, ‘just like us’ – only richer, more talented, or perhaps better looking. But what about when celebrities are not ‘just like us’? Despite relatively recent changes in the representation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) life in the media, the world of celebrity is an overwhelmingly heterosexual one. -

Deconstructing the Children's Culture Industry

DECONSTRUCTING THE CHILDREN‘S CULTURE INDUSTRY: A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS FROM YOUNG PEOPLE by JENNIFER ANN HILL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) (Social Work, Sociology, Psychology,) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) April 2013 © Jennifer Ann Hill, 2013 ABSTRACT The children‘s ―culture industry,‖ meaning the mass production of popular culture by corporations, has systematically targeted children to persuade them to desire commodities while promising an increase in happiness. Media in all forms has become the conduit through which corporations have access to children and the means by which they influence, mould and profoundly impact children's lives. Indeed, consumer culture plays a dominant role for individuals living in such cultures, arguably more than any other institution including government. In the 1990s, the most intense commercial campaign in the history of childhood had commenced. Despite the pervasiveness of consumerism, there has been a notable gap in the literature to ascertain from young people, in their own words, what are the experiences of and meanings attributed to consumerism throughout their childhoods. Using a paradigm of qualitative research, the present dissertation provides a detailed description of how young people, those aged 18 or 19, perceive the presence of consumer culture in their lives, both presently and with particular focus on the past, as children. Data presented here suggest that most of the young people interviewed feel considerable pressure to conform to the standards of consumerism, including the adoption of brand culture, fads and a ‗buy-and-consume‘ modality. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Chinese Women’s Makeover Shows: Idealised Femininity, Self-presentation and Body Maintenance Xiaoyi Sun Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2014 1 Declaration This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: 2 Abstract Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Chinese television industry has witnessed the rise of a new form of television programme, Chinese Women’s Makeover Shows. These programmes have quickly become a great success and have received enormous attention from growing audiences. The shows are themed on educating and demonstrating to the audiences the information and methods needed to beautify their faces and bodies and consume products accordingly. -

About - David Lachapelle

About - David LaChapelle BIO EXHIBITIONS Upcoming / Current Exhibitions Bling Bling Baby Show,NRW Forum, Dusseldorf, Germany, November 19, 2016 January 15, 2017 Solo Exhibition, Ara Modern Art Museum, Seoul, South Korea, November 18, 2016 February 26, 2017 Art FairParis Photo Art Fair, Paris France, November 10 13, 2016 Solo Exhibition, Usina del Arte, Buenos Aires, Argentina, October 29 December 31, 2016 Art Fair, Ch. ACO Art Fair, Santiago, Chile, October 14 16, 2016 Iluminación , Fundación Unión, Montevideo, Uruguay, June 24 October 7, 2016 Solo Museum + Public Exhibitions 2016 Símbolos de inmortalidad , Museo Agadu, Montevideo, Uruguay, June 22 August 26, 2016 Art Fair, Exposition Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, September 23 September 25, 2016 David LaChapelle: Gas Stations , Edward Hopper House, Nyack, New York, July 9 September 11, 2016 Posmodernidad , Espacio De Arte Contemporaneo, Montevideo, Uruguay, June 9 August 26, 2016 Contemporaneidad , Centro De La Fotografia, Montevideo, Uruguay, June 24 September 4, 2016 Pipe Dream , Galerie Andrea Caratsch, Zurich, Switzerland, December 10 February 19, 2016 The Armory Show, Piers 92 & 94, New York City, NY, March 36, 2016 AIPAD:The Photography Show, The Park Avenue Armory, New York City, NY, April 14 17, 2016 2015 Festival Foto Industria 02, Bologna, Italy, October 2 – November 1, 2015 David LaChapelle: Dopo Il Diluvio Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, Italy, April 29 – September 20 1/12 About - David LaChapelle Fotografias 1984 – 2013 Museum of Contemporary Art Chile, Santiago, Chile, July 29September 27 Fotografias 1984 – 20100013 Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima, Peru, January 23 – April 13 2014 Land Scape Public exhibition at bus stop R / Aldwych, London, UK, September 12 – 22 Once in the Garden OstLicht. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Rupaul's Drag Race

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. ii While most scholars analyze RuPaul’s Drag Race primarily through content analysis of the aired television episodes, this dissertation combines content analysis with ethnography in order to connect the television show to tangible practices among fans and effects within drag communities.