'Just Like Us'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Annual Report 2018/ 19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018/ 19 midsumma.org.au Midsumma Festival 2018/ 19 Annual Report Image: The Odditorium Image by Suzanne Balding CONTENTS featuring Miss Amy Cover image: by Alexis Desaulniers-Lea and artwork by Matto Lucas featuring Wade Tuck. What is Midsumma Festival? 4 Chair’s Report 7 2019 Midsumma Festival Highlights 8 2019 Economic Overview 10 2019 Program Overview and Highlights 12 - Summary of Festival Attendance 16 - Signature Events 17 - Midsumma Presents Program 22 - Open Access Program 27 - Events Outside of Festival Season 29 Focus Areas in 2019 31 2019 Access Initiatives and Activities 36 2019 Artistic Outcomes 40 Who Are Our Audiences? 42 Our Reach 44 Treasurer's Report 46 2019 Financial Report 47 Our People 56 Our Partners 58 Appendix 59 3 Midsumma Festival 2018/ 19 Annual Report Midsumma Festival also holds two annual WHAT IS signature events – Midsumma Carnival MIDSUMMA and Midsumma Pride March. Midsumma Carnival opens the Festival with a one FESTIVAL? day celebration at Alexandra Gardens in Melbourne’s CBD and Midsumma Pride Midsumma Festival March is held on the third weekend of the is Australia’s premier Festival each year flowing through Fitzroy St in St Kilda to the foreshore of Catani WHAT LGBTQIA+ arts and cultural Gardens. DO WE DO? festival held annually in Although the primary festival is held each year in summer, Midsumma works year- • We create inclusive safe cultural and Melbourne for and by round to provide queer artists, social- social spaces. communities who live changers and culture-makers with support, • We lead conversations and we listen. platforms and tools to create, present and with shared experiences promote their work, connect with their • We champion collaboration. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Quest Volume 16 Issue 21

MODEST TURNOUT, MIXED MESSAGES FOR MADISON EQUALITY MARCH Madison - Sunny skies and brisk 20 degree tem - peratures greeted a crowd estimated between 100 to 200 marching for LGBT equality and more here December 5. Inspired by the National Equality March last October, Unified For Equality (UFE), a coalition of Madison and southern Wisconsin LGBT groups, organized the march and rally on the Capitol steps as a local follow-up to the Washington DC event. And, as often happens in coalition building, mes - sages at the rally became mixed. Quest correspondent Steve Vargas pegged the total at a little over one hundred, while rally organizers offered a more optimistic estimate of about 200. The march also briefly interrupted a Fair Wisconsin board of directors meeting when it passed the statewide organization’s State Street offices shortly after Noon. One board member told Quest the marchers “num - bered about 120.” In addition to calling attention to the recent Wis - consin Supreme Court hearing of McConkey lawsuit challenging that validity of the 2006 “Marriage Pro - tection” Amendment referendum, the rally’s focus Madison; OutReach/OutThere of Madison; P.E.A.C.E. Amendment and an executive order to overturn the expanded to include speakers advocating universal at UW-Whitewater and others. Organizers made “Don’t-Ask-Don’t-Tell” policy for military personnel. health care and protesting the ongoing wars in Iraq heavy use of email text and the social networking According to the UFE press release that announced and Afghanistan - especially President Obama’s De - site Facebook to promote the event. UFE spokesper - the march, the LGBT community “lacks everyday cember 1 decision to add 30,000 troops to the lat - son Jessie Otradovec reported that she was happy rights in addition to the marriage right and refuses ter battle theater. -

The Tiger's Tale

sNyder high schOOl 3801 austiN ave. the tiger’s sNyder, tx 79549 tale Volume 102 Oct. 25, 2019 No. 2 Sophomore talks about experiences with diabetes By Ryleigh Tinkler said. he’ll give himself a little insulin. fluids and insulin. He had to Staff Writer Will has type 1 diabetes Will gives himself insulin before have xrays done and had to Sophomore Will Haley has and uses an insulin pump to he eats and then before he does give blood every hour. He was lived more than half of his life get insulin. His insulin pump a big activity. in the emergency room from with diabetes sticks to his arm and he has to His blood sugar levels also 9:30 a.m.-2:30 a.m. the next “I was diagnosed at four change it every three days. He affect his moods and emotions. morning. If Will hadn’t gone years old. Two weeks after I can track his blood sugar with “If my blood sugar is high, I to the hospital when he did, his turned four. And my current an app on his phone. Will has a can be annoying and the worst kidneys could have failed and age is 15. So, I’ve had it for friend from his diabetes camp, in the world. Mentally, it’s got he could have also had nerve about 11 years,” Will said. who can also see his blood me in some places because a lot damage. He might have had to Will’s mom was the first one sugar count. -

Australia and Indonesia Remain the 'Odd Couple' of Southeast Asia Tim

Australia and Indonesia Remain the ‘Odd Couple’ of Southeast Asia Tim Lindsey The recent meeting on Batam between Prime Minister John Howard and President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was widely reported as a critical moment in the Australia Indonesia relationship. The two leaders kissed and made up and announced that the rift caused by the arrival of Papuan asylum seekers and the release of Abu Bakar Bashir had been resolved: the latest crisis in Indonesian/Australia relations was over. Except that it was never a crisis. There was, in reality, no concrete issue in dispute between the two countries: no concession was given by either leader in Batam and, in fact, none were sought. The ‘reconciliation’ required nothing, because there had never been any real split between the two governments. The letters exchanged between the two leaders before their Batam date make this clear, basically agreeing on the key issues and reaffirming the status quo: • Bashir is a threat, but his release was a matter for Indonesia’s legal process and can’t be interfered with. • Indonesia’s sovereignty over Papua is supported by Australia but the grant of visas to 42 Papuans was a matter for Australian legal process and can’t be interfered with. So where was the supposed bilateral crisis that hogged headlines for weeks and resulted in the recall of the Indonesian ambassador? It was largely symbolic, comprising formalistic government responses to controversies created by legislators on both sides of the Arafura Sea. In Australia, Jakarta is always an easy target to kick around to embarrass the government of the day, as Australian Shadow Foreign Minister, Kevin Rudd has been doing lately. -

Bury Your Gays’

. Volume 15, Issue 1 May 2018 Toxic regulation: From TV’s code of practices to ‘#Bury Your Gays’ Kelsey Cameron, University of Pittsburgh, USA Abstract: In 2016, American television killed off many of its queer female characters. The frequency and pervasiveness of these deaths prompted outcry from fans, who took to digital platforms to protest ‘bury your gays,’ the narrative trope wherein queer death serves as a plot device. Scholars and critics have noted the positive aspects of the #BuryYourGays fan campaign, which raised awareness of damaging representational trends and money for the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention organization focused on LGBTQ youth. There has been less attention to the ties #BuryYourGays has to toxicity, however. Protests spilled over into ad hominem attacks, as fans wished violence upon the production staff responsible for queer character deaths. Using the death of The 100 character Lexa as a case study, this article argues that we should neither dismiss these toxic fan practices nor reduce them to a symptom of present-day fan entitlement. Rather, we must attend to the history that shapes contemporary antagonisms between producers and queer audiences – a history that dates back to television’s earliest efforts at content regulation. Approaching contemporary fandom through history makes clear that toxic fan practices are not simply a question of individual agency. Longstanding industry structures predispose queer fans and producers to toxic interactions. Keywords: queer fandom, The 100, television, regulation, ‘bury your gays’ Introduction In March of 2016, queer fans got angry at American television. This anger was both general and particular, grounded in long-simmering dissatisfaction with TV’s treatment of queer women and catalyzed by a wave of character deaths during the 2016 television season. -

Joel Creasey

JOEL CREASEY “Creasey is an unstoppable force and the crown prince of Aussie comedy.” - The Daily Telegraph Joel Creasey is one of Australia's most-popular, acclaimed and charmingly controversial stand-up comedians. A self-described shameless "fame whore", Joel has become a television staple in Australia. This year alone, Joel has captained his team to (occasional) victory on the first season of Channel Ten’s newest studio-based comedy series, Show Me The Movie!, along with enemy-captain Jane Harber and host Rove McManus. Ten Network has just announced a second season. Joel also made his soap star debut on one of Australia’s favourite TV shows, Neighbours. It was recently announced that Joel shall be Australia’s newest and frankly loosest, cupid – hosting the worldwide phenomenon dating show, ‘Take Me Out’, on Network Seven. To add to a very busy television year, Joel was chuffed to see his stand up special, recorded at the esteemed Sydney Opera House, air on Network Ten. A prestigious honour that not many stand-up comedians have achieved. Landing the much coveted role as co-host of SBS’s ‘Eurovision Song Contest’ alongside Myf Warhurst in 2017, Joel and Myf returned in 2018 for the global event described as the Olympics of song contests. Joel caused international headlines this year during his commentary, when a stage invader attempted to grab the microphone during the UK’s performance. Reacting without hesitation, Joel said “what an absolute cockhead”, a quote that immediately went viral worldwide. Even JK Rowling heard the quote and instantly praised his candour, awarding him an ‘Order of Merlin First Class’, a title only held by 11 people in the world (yes, it’s really a thing and Joel’s proudest achievement to date). -

The Rhetorics of the Voltron: Legendary Defender Fandom

"FANS ARE GOING TO SEE IT ANY WAY THEY WANT": THE RHETORICS OF THE VOLTRON: LEGENDARY DEFENDER FANDOM Renee Ann Drouin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2021 Committee: Lee Nickoson, Advisor Salim A Elwazani Graduate Faculty Representative Neil Baird Montana Miller © 2021 Renee Ann Drouin All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Lee Nickoson, Advisor The following dissertation explores the rhetorics of a contentious online fan community, the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom. The fandom is known for its diversity, as most in the fandom were either queer and/or female. Primarily, however, the fandom was infamous for a subsection of fans, antis, who performed online harassment, including blackmailing, stalking, sending death threats and child porn to other fans, and abusing the cast and crew. Their motivation was primarily shipping, the act of wanting two characters to enter a romantic relationship. Those who opposed their chosen ship were targets of harassment, despite their shared identity markers of female and/or queer. Inspired by ethnographically and autoethnography informed methods, I performed a survey of the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom about their experiences with harassment and their feelings over the show’s universally panned conclusion. In implementing my research, I prioritized only using data given to me, a form of ethical consideration on how to best represent the trauma of others. Unfortunately, in performing this research, I became a target of harassment and altered my research trajectory. In response, I collected the various threats against me and used them to analyze online fandom harassment and the motivations of antis. -

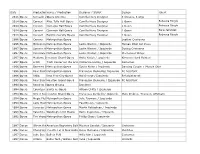

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

Seeing Culture, Seeing Schapelle Schapelle Corby As (Inter)National Visual Event Anthony Lambert, Macquarie University, Australia

Seeing Culture, Seeing Schapelle Schapelle Corby as (Inter)National Visual Event Anthony Lambert, Macquarie University, Australia Abstract: The recent arrest and conviction of Australian Schapelle Corby on charges of drug smuggling in Indonesia ignited a range of national and international political and racialised tensions. This paper explores the Schapelle Corby phenomenon as an intersection of events and practices across the field of visual culture. It places the analysis of Schapelle Corby related visual texts and associated sites within an examination of history, national identity, national security and public memory. Thus the paper seeks to articulate and explore Australia’s place within the Asia-Pacific, and the resurgence of nationalistic and neocolonial discourses within the contexts of globalisation and the 'war on terror'. Keywords: Visual Culture, Terror, Representation, National Identity HIS PAPER EXAMINES the cultural sig- event that, like so many others, would test the mettle nificance of the case of Australian Schapelle of the Australian-Indonesian relationship. Corby, a TCorby, a young woman arrested for import- 27-year-old Queensland woman caught with 4.1 ing marijuana into Bali, Indonesia. Images kilograms of marijuana hidden in her boogy board of young Australians falling foul of Asian drug laws bag at Bali airport, maintained that the drugs had occupy a larger and more powerful place in Australi- been planted in her unlocked bag by airport baggage- an culture than ever before. This is primarily to do handlers somewhere between the Gold Coast, Sydney with the Schapelle Corby case, the very public event and Denpasar. In the early days of her trial it was it became and the range of contemporary issues it thought she might receive the death sentence. -

Independent Report Misinformation and Exploitation of the White

Strictly Confidential © The Hidden World Research Group Independent Report Misinformation and Exploitation of the White Powder Hoax www.expendable.tv The Expendable Project CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 The Background 1.2 White Powder Hoaxes 2. Exploitation & Impact 2.1 The Government’s Reaction 2.2 Public Impact 3. Misinformation & Manipulation 3.1 The Picture 3.2 The Chronological Truth 4. Summary [Introduction] 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE BACKGROUND In June 2005, in the wake of the verdict and sentence in the Bali trial, public support for Schapelle Corby was at an unprecedented level. The public were aware of a number of the fundamental facts of the case, and thus of Schapelle Corby’s self evident innocence. This placed the government in an extremely difficult position. They were well aware of the many human rights abuses at the trial. They were also well aware of the systemic criminality at Australian airports, and within the AFP. As documented throughout the Expendable Project, they had also adopted a policy which ultimately entailed the withholding of vital primary evidence, the misleading of parliament, and engagement in a series of other disturbing acts which spiralled them into an abyss. The expectation of the Australian public, that their government would act to secure the prompt release of Schapelle Corby, therefore created intense pressure. It was also clear that changing public opinion, through media management, would not be a short term process. However, a situation arose which they were able to exploit, and manipulate, to make dramatic inroads into altering public perception. Expendable.TV Page 1 - 1 [Introduction] 1.2 WHITE POWDER HOAXES Between 2001 and 2005 there were 360 white-powder hoaxes in Australia.