Exporting Pine Nuts to Europe 1. Product Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Wood Forest Products from Conifers

Page 1 of 8 NON -WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 12 Non-Wood Forest Products From Conifers FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-37 ISBN 92-5-104212-8 (c) FAO 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 - AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONIFERS WHAT ARE CONIFERS? DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE USES CHAPTER 2 - CONIFERS IN HUMAN CULTURE FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY RELIGION POLITICAL SYMBOLS ART CHAPTER 3 - WHOLE TREES LANDSCAPE AND ORNAMENTAL TREES Page 2 of 8 Historical aspects Benefits Species Uses Foliage effect Specimen and character trees Shelter, screening and backcloth plantings Hedges CHRISTMAS TREES Historical aspects Species Abies spp Picea spp Pinus spp Pseudotsuga menziesii Other species Production and trade BONSAI Historical aspects Bonsai as an art form Bonsai cultivation Species Current status TOPIARY CONIFERS AS HOUSE PLANTS CHAPTER 4 - FOLIAGE EVERGREEN BOUGHS Uses Species Harvesting, management and trade PINE NEEDLES Mulch Decorative baskets OTHER USES OF CONIFER FOLIAGE CHAPTER 5 - BARK AND ROOTS TRADITIONAL USES Inner bark as food Medicinal uses Natural dyes Other uses TAXOL Description and uses Harvesting methods Alternative -

Phytosociological Analysis of Pine Forest at Indus Kohistan, Kpk, Pakistan

Pak. J. Bot., 48(2): 575-580, 2016. PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF PINE FOREST AT INDUS KOHISTAN, KPK, PAKISTAN ADAM KHAN1, MOINUDDIN AHMED2, MUHAMMAD FAHEEM SIDDIQUI*3, JAVED IQBAL1 AND MUHAMMAD WAHAB4 1Laboratory of plant ecology and Dendrochronology, Department of Botany, Federal Urdu University, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Campus Karachi, Pakistan 2Department of Earth and Environmental Systems, 600 Chestnut Street Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN, USA 3Department of Botany, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan 4Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract The study was carried out to describe the pine communities at Indus Kohistan valley in quantitative term. Thirty stands of relatively undisturbed vegetation were selected for sampling. Quantitative sampling was carried out by Point Centered Quarter (PCQ) method. Seven tree species were common in the Indus Kohistan valley. Cedrus deodara was recorded from twenty eight different locations and exhibited the highest mean importance value while Pinus wallichiana was recorded from 23 different locations and exhibited second highest mean importance value. Third most occurring species was Abies pindrow that attained the third highest mean importance value and Picea smithiana was recorded from eight different locations and attained fourth highest importance value while it was first dominant in one stand and second dominant in four stands. Pinus gerardiana, Quercus baloot and Taxus fuana were the rare species in this area, these species attained low mean importance value. Six communities and four monospecific stands of Cedrus deodara were recognized. Cedrus-Pinus community was the most occurring community, which was recorded from 13 different stands. -

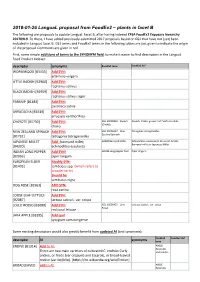

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Biodiversity Conservation in Botanical Gardens

AgroSMART 2019 International scientific and practical conference ``AgroSMART - Smart solutions for agriculture'' Volume 2019 Conference Paper Biodiversity Conservation in Botanical Gardens: The Collection of Pinaceae Representatives in the Greenhouses of Peter the Great Botanical Garden (BIN RAN) E M Arnautova and M A Yaroslavceva Department of Botanical garden, BIN RAN, Saint-Petersburg, Russia Abstract The work researches the role of botanical gardens in biodiversity conservation. It cites the total number of rare and endangered plants in the greenhouse collection of Peter the Great Botanical garden (BIN RAN). The greenhouse collection of Pinaceae representatives has been analysed, provided with a short description of family, genus and certain species, presented in the collection. The article highlights the importance of Pinaceae for various industries, decorative value of plants of this group, the worth of the pinaceous as having environment-improving properties. In Corresponding Author: the greenhouses there are 37 species of Pinaceae, of 7 geni, all species have a E M Arnautova conservation status: CR -- 2 species, EN -- 3 species, VU- 3 species, NT -- 4 species, LC [email protected] -- 25 species. For most species it is indicated what causes depletion. Most often it is Received: 25 October 2019 the destruction of natural habitats, uncontrolled clearance, insect invasion and diseases. Accepted: 15 November 2019 Published: 25 November 2019 Keywords: biodiversity, botanical gardens, collections of tropical and subtropical plants, Pinaceae plants, conservation status Publishing services provided by Knowledge E E M Arnautova and M A Yaroslavceva. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons 1. Introduction Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and Nowadays research of biodiversity is believed to be one of the overarching goals for redistribution provided that the original author and source are the modern world. -

Tree and Shrub Guide

tree and shrub guide • Problems & Challenges in Western Colorado • Purchasing A High Quality Tree • Summer & Winter Watering Tips • Best Time to Plant • Tree Planting Steps • Plant Suggestions for Grand Valley Landscapes Welcome Tree and Shrub Planters The Grand Junction Forestry Board has assembled the following packet to assist you in overcoming planting problems and challenges in the Grand Valley. How to choose a high quality tree, watering tips, proper planting techniques and tree species selection will be covered in this guide. We encourage you to further research any unknown variables or questions that may arise when the answers are not found in this guide. Trees play an important role in Grand Junction by improving our environment and our enjoyment of the outdoors. We hope this material will encourage you to plant more trees in a healthy, sustainable manner that will benefit our future generations. If you have any questions please contact the City of Grand Junction Forestry Department at 254-3821. Sincerely, The Grand Junction Forestry Board 1 Problems & Challenges in Western Colorado Most Common Problems • Plan before you plant – Know the characteristics such as mature height and width of the tree you are going to plant. Make sure the mature plant will fit into the space. • Call before digging - Call the Utility Notification Center of Colorado at 800-922-1987. • Look up – Avoid planting trees that will grow into power lines, other wires, or buildings. • Do a soil test - Soils in Western Colorado are challenging and difficult for some plants to grow in. Make sure you select a plant that will thrive in your planting site. -

Disturbances Influence Trait Evolution in Pinus

Master's Thesis Diversify or specialize: Disturbances influence trait evolution in Pinus Supervision by: Prof. Dr. Elena Conti & Dr. Niklaus E. Zimmermann University of Zurich, Institute of Systematic Botany & Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL Birmensdorf Landscape Dynamics Bianca Saladin October 2013 Front page: Forest of Pinus taeda, northern Florida, 1/2013 Table of content 1 STRONG PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL IN PINE TRAITS 5 1.1 ABSTRACT 5 1.2 INTRODUCTION 5 1.3 MATERIAL AND METHODS 8 1.3.1 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 8 1.3.2 TRAIT DATA 9 1.3.3 PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL 9 1.4 RESULTS 11 1.4.1 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 11 1.4.2 PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL 12 1.5 DISCUSSION 14 1.5.1 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 14 1.5.2 PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL 16 1.6 CONCLUSION 17 1.7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 17 1.8 REFERENCES 19 2 THE ROLE OF FIRE IN TRIGGERING DIVERSIFICATION RATES IN PINE SPECIES 21 2.1 ABSTRACT 21 2.2 INTRODUCTION 21 2.3 MATERIAL AND METHODS 24 2.3.1 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 24 2.3.2 DIVERSIFICATION RATE 24 2.4 RESULTS 25 2.4.1 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 25 2.4.2 DIVERSIFICATION RATE 25 2.5 DISCUSSION 29 2.5.1 DIVERSIFICATION RATE IN RESPONSE TO FIRE ADAPTATIONS 29 2.5.2 DIVERSIFICATION RATE IN RESPONSE TO DISTURBANCE, STRESS AND PLEIOTROPIC COSTS 30 2.5.3 CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE ANALYSIS PATHWAY 33 2.5.4 PHYLOGENETIC INFERENCE 34 2.6 CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK 34 2.7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 2.8 REFERENCES 36 3 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 39 3.1 S1 - ACCESSION NUMBERS OF GENE SEQUENCES 40 3.2 S2 - TRAIT DATABASE 44 3.3 S3 - SPECIES DISTRIBUTION MAPS 58 3.4 S4 - DISTRIBUTION OF TRAITS OVER PHYLOGENY 81 3.5 S5 - PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL OF 19 BIOCLIM VARIABLES 84 3.6 S6 – COMPLETE LIST OF REFERENCES 85 2 Introduction to the Master's thesis The aim of my master's thesis was to assess trait and niche evolution in pines within a phylogenetic comparative framework. -

Studies on Drying, Packaging and Storage of Solar Tunnel Dried Chilgoza Nuts

Available online a t www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Archives of Applied Science Research, 2012, 4 (3):1311-1319 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html) ISSN 0975-508X CODEN (USA) AASRC9 Studies on drying, packaging and storage of solar tunnel dried chilgoza nuts N. S Thakur, Sharma S, Joshi V. K, Thakur K. S and Jindal N Department of Food Science and Technology, Dr YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni-Solan, HP ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Chilgoza (Pinus gerardiana) is one of the pine nuts among six species found in India which produce edible nuts. Because of the traditional handling of this nut by tribals, it lasts only for few weeks in the market. Studies were undertaken to compare the solar drying modes for drying of this nut and screen out the suitable packaging material for its storage. Extracted nuts were dried under three solar drying means like solar cabinet drier (46-52 ⁰C), solar tunnel drier (43-47 ⁰C) and open sun (18-22 ⁰C). Solar tunnel drier was found to be best drying mode for drying quality nuts as compare to the others. So, nuts dried in this drier were packed in five different packaging materials and stored under ambient conditions for six months. The some physico-chemical quality characteristics like a w (0.208), oil (49.1%) total carbohydrates ( 24.9%), and proteins ( 11.8%) and sensory quality attributes of packed nuts were retained better in glass jars closely followed by aluminum laminate pouch after six months of storage as compared to others. Solar tunnel drier was the best drying mode and glass jar as well as aluminum laminate pouch were the best materials for packaging and storage. -

Pinus Edulis Engelm. Family: Pinaceae Pinyon

Pinus edulis Engelm. Family: Pinaceae Pinyon The genus Pinus is composed of about 100 species native to temperate and tropical regions of the world. Wood of pine can be separated microscopically into the white, red and yellow pine groups. The word pinus is the classical Latin name. The word edulis means edible, referring to the large seeds, known as pinyon nuts, pine nuts and pinones. Other Common Names: Arizona pijn, Arizona pine, Arizona-tall, Colorado pijn, Colorado pine, Colorado pinyon, foxtail pine, nut pine, pin d'Arizona, pinien-nussbaum, pino di Colorado, pinon, pinyon, pinyon Colorado, two leaf pinyon, two needle pinyon. Distribution: Pinyon is native to the southern Rocky Mountain region, predominantly in the foothills, from Colorado and Utah south to central Arizona and southern New Mexico. Also locally in southwestern Wyoming, extreme northwestern Oklahoma, the Trans-Pecos area of Texas, southeastern California and northwestern Mexico (Chihuahua). The Tree: Pinyon trees reach heights of 10 to 51 feet, with diameters of 6 to 30 inches, depending on site conditions. An exceptionally large specimen was recorded at 69 feet tall, with a diameter of over 5 feet. Pinyons generally are small trees, growing less than 35 feet tall, with diameters less than 18 inches. Pinyons are long lived, growing for 75 to 200 years, with dominant trees being 400 years old. Pinyons 800 to 1,000 years old have been recorded. General Wood Characteristics: The wood of pinyon is moderately heavy compared to other pines. It is slow grown and often knotty, but strong. The heartwood is yellow. Mechanical Properties (2-inch standard) Compression Specific MOE MOR Parallel Perpendicular WMLa Hardness Shear gravity GPa MPa MPa MPa KJ/m3 N MPa Green 0.50 4.48 33.1 17.9 3.31 52.4 2670 6.34 Dry 0.57 7.86 53.8 44.1 10.5 32.4 3820 NA aWML = Work to maximum load. -

Culture of Gymnosperm Tissue in Vitro

Culture of Gymnosperm tissue in vitro R.N. Konar and Chitrita Guha Department ofBotany, University ofDelhi, Delhi 7, India SUMMARY A review is given of recent advances in the culture of vegetative and repoductive tissues of Gymnosperms. Gymnosperm tissue culture is still in its infancy as compared to its angiosperm of efforts raise counterpart. In spite numerous to cultures from time to time little success has so far been achieved. 1. CULTURE OF VEGETATIVE PARTS Growth and development of callus Success in maintaining a continuous culture of coniferous tissue in vitro was first reported by Ball (1950). He raised tissues from the young adventive shoots burls of growing on the Sequoia sempervirens on diluted Knop’s solution with 3 per cent sucrose and 1 ppm 1AA. Marginal meristems, cambium-like meris- around of tracheids and cells could be tems groups mature parenchymatous distinguished in the callus mass. The parenchymatous cells occasionally con- tained tannin. the of tannin is According to Ball (1950) anatomically presence not inconsistent with the normal function of the shoot apex. He considered that probably the tannin cells have less potentialities to develop. Reinert & White (1956) cultured the normal and tumorous tissues of Picea glauca. They excised the cambial region from the tumorous (characteristic ofthe species) and non-tumorous portions of tumor bearing trees and also cambium from normal trees. This work was carried out with a view to understand the de- gree ofmalignancy of the cells and the biochemical characteristics of the tumors. They developed a rather complex nutrient medium consisting of White’s mine- rals, 16 amino acids and amides, 8 vitamins and auxin to raise the cultures. -

Reommended Trees for Colo Front Range Communities.Pmd

Recommended Trees for Colorado Front Range Communities A Guide for Selecting, Planting, and Caring For Trees Do Not Top Your Trees! http://csfs.colostate.edu www.coloradotrees.org Trees that have been topped may become hazardous and unsightly. Avoid topping trees. Topping leads to: • Starvation www.fs.fed.us • Shock • Insects and diseases • Weak limbs • Rapid new growth • Tree death • Ugliness Special thanks to the International Society of Arboriculture for • Increased maintenance costs providing details and drawings for this brochure. Eastern redcedar* (Juniperus virginiana) Tree Selection Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree, green summer foliage, rusty brown in the winter Tree selection is one of the most important investment decisions a home owner makes when landscaping a new home or replacing a Rocky Mountain juniper* (Juniperus scopulorum) tree lost to damage or disease. Most trees can outlive the people Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree who plant them, therefore the impact of this decision is one that can influence a lifetime. Matching the tree to the site is critical; the following site and tree demands should be considered before buying and planting a tree. Trees to avoid! Site Considerations Selecting the right tree for the right place can help reduce the potential • Available space above and below ground for catastrophic loss of trees by insects, disease or environmental factors. We can’t control the weather, but we can use discernment in • Water availability selecting trees to plant. A variety of tree species should be planted so no • Drainage single species represents more than 10-15 percent of a community’s • Soil texture and pH total tree population. -

Pine Nuts: a Review of Recent Sanitary Conditions and Market Development

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 July 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201707.0041.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Forests 2017, 8, 367; doi:10.3390/f8100367 Article Pine nuts: a review of recent sanitary conditions and market development Hafiz Umair M. Awan 1 and Davide Pettenella 2,* 1 Department of Forest Science, University of Helsinki, Finland; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department Land, Environment, Agriculture and Forestry – University of Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-049-827-2741 Abstract: Pine nuts are non-wood forest products (NWFP) with constantly growing market notwithstanding a series of phytosanitary issues and related trade problems. The aim of paper is to review the literature on the relationship between phytosanitary problems and trade development. Production and trade of pine nuts in Mediterranean Europe have been negatively affected by the spreading of Sphaeropsis sapinea (a fungus) associated to an adventive insect Leptoglossus occidentalis (fungal vector), with impacts on forest management activities, production and profitability and thus in value chain organization. Reduced availability of domestic production in markets with growing demand has stimulated the import of pine nuts. China has become a leading exporter of pine nuts, but its export is affected by a symptom associated to the nuts of some pine species: the ‘pine nut syndrome’ (PNS). Most of the studies embraced during the review are associated to PNS occurrence associated to the nuts of Pinus armandii. In the literature review we highlight the need for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of the pine nuts value chain organization, where research on food properties and clinical toxicology be connected to breeding and forest management, forest pathology and entomology and trade development studies. -

PINUS L. Pine by Stanley L

PINAS Pinaceae-Pine family PINUS L. Pine by Stanley L. Krugman 1 and James L. Jenkinson 2 Growth habit, occurrence, and use.-The ge- Zealand; P. canariensis in North Africa and nus Pinus, one of the largest and most important South Africa; P. cari.bea in South Africa and of the coniferous genera, comprises about 95 Australia; P. halepereszs in South America; P. species and numerous varieties and hybrids. muricata in New Zealand and Australia; P. Pines are widely distributed, mostly in the sgluestris, P, strobus, P. contorta, and P. ni'gra Northern Hemisphere from sea level (Pi'nus in Europe; P. merkusii in Borneo and Java 128, contorta var. contorta) to timberline (P. albi- 152, 169, 266). cantl;i,s). They range from Alaska to Nicaragua, The pines are evergreen trees of various from Scandinavia to North Africa. and from heights,-often very tall but occasionally shrubby Siberia to Sumatra. Some species, such as P. (table 3). Some species, such as P.lnmbertionn, syluestris, are widely distributed-from Scot- P. monticola, P. ponderosa, antd. P. strobtr's, grow land to Siberia-while other species have re- to more than 200 feet tall, while others, as P. stricted natural ranges. Pinus canariensis, for cembroides and P. Ttumila, may not exceed 30 example, is found naturally only on the Canary feet at maturity. Islands, and P. torreyana numbers only a few Pines provide some of the most valuable tim- thousand individuals in two California localities ber and are also widely used to protect water- (table 1) (4e). sheds, to provide habitats for wildlife, and to Forty-one species of pines are native to the construct shelterbelts.