Burkina Faso/Niger)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized Towns in the Light of Their Constraints and Opportunities - the Case of Nevers (Burgundy - France)

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Navarre, Françoise; Delpirou, Aurelien Conference Paper Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized towns in the light of their constraints and opportunities - the case of Nevers (Burgundy - France) 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Navarre, Françoise; Delpirou, Aurelien (2014) : Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized towns in the light of their constraints and opportunities - the case of Nevers (Burgundy - France), 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124545 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

ESPON PROFECY D5 Annex 17. 10 Additional

PROFECY – Processes, Features and Cycles of Inner Peripheries in Europe (Inner Peripheries: National territories facing challenges of access to basic services of general interest) Applied Research Final Report Annex 17 Brief Overview of 10 IP Regions in Europe Version 07/12/2017 This applied research activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Paulina Tobiasz-Lis, Karolina Dmochowska-Dudek, Marcin Wójcik, University of Lodz, (Poland) Mar Ortega-Reig, Hèctor del Alcàzar, Joan Noguera, Institute for Local Development, University of Valencia (Spain) Andrew Copus, Anna Berlina, Nordregio (Sweden) Francesco Mantino, Barbara Forcina, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (Italy) Sabine Weck, Sabine Beißwenger, Nils Hans, ILS Dortmund (Germany) Gergely Tagai, Bálint Koós, Katalin Kovács, Annamária Uzzoli, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (Hungary) Thomas Dax, Ingrid Machold, Federal Institute for Less Favoured and Mountainous Areas (BABF) (Austria) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Barbara Acreman and Zaira Piazza (Italy), Eedi Sepp (Estonia), Zsolt Szokolai, European Commission. ESPON EGTC: Marjan van Herwijnen (Project Expert), Laurent Frideres (HoU E&O), Ilona Raugze (Director), Piera Petruzzi (Outreach), Johannes Kiersch (Financial Expert). Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. -

Belgium Regions Programme Booklet a Europe That Matters!

A EUROPE THAT MATTERS! REPRESENTING LOCAL ACTORS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: PERCEPTIONS OF EU POLICY OBJECTIVES AND REGIONAL INFLUENCE Brendan Bartels, Solène David, Anastasia Donica, Alexis Gourdain, Diego Grippa, Daniele Ietri, Juuso Järviniemi, Théo Prestavoine A EUROPE THAT MATTERS! REPRESENTING LOCAL ACTORS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: PERCEPTIONS OF EU POLICY OBJECTIVES AND REGIONAL INFLUENCE Brendan Bartels, Solène David, Anastasia Donica, Alexis Gourdain, Diego Grippa, Daniele Ietri, Juuso Järviniemi, Théo Prestavoine CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. ANALYSIS OF THE MAIN TOPICS BY THEME 10 4. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 18 5. CONCLUSION 20 REFERENCES 22 INTERVIEWS 24 ANNEX I 27 ANNEX II 34 NOTES 42 Please cite as: Bartels, B., David, S., Donica, A., Gourdain, A., Grippa, D., Ietri, D., Järvin- iemi, J., Prestavoine, T., A Europe that Matters! Representing Local Actors in the Euro- pean Union: Perceptions of EU Policy Objectives and Regional Influence. 89 Initiative. 1.INTRODUCTION Does the European project struggle to present itself in a mea- ningful way to local communities, especially when they are far from metropolitan areas and centers of decision making? The divide between urban and non-urban areas seems to be signi- ficantly divisive in this respect. While in recent years efforts to reach out to local communities have multiplied and “periphe- ral” or “inner” areas have got more attention, much remains unknown about local communities’ perceptions, understanding and implementation of EU policies at the local level. Additional- ly, it is not clear to what extent local communities far from the main centers of decision making are able to represent themsel- ves and their policy priorities to higher levels of government. -

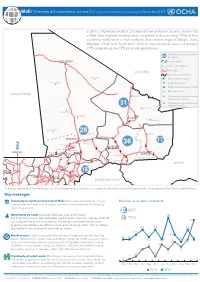

Humanitarian Access (Summary of Constraints from January to December 2017)

Mali: Overview of humanitarian access (summary of constraints from January to December 2017) In 2017, OCHA recorded 133 cases of humanitarian access constraints in Mali (the highest number ever recorded in the country). 97% of the incidents took place in the northern and central regions (Mopti, Gao, Ménaka, Kidal and Timbuktu). 41% of the incidents were robberies, 27% carjackings and 9% physical aggression. Number of access constraints xx by region TAOUDÉNIT Limit of region Limit of new regions ALGERIA Main road International boundaries Achourat! Non-functional airport Foum! Elba Functional airport Regional administrative centre ! Populated place MAURITANIA ! Téssalit Violence against humanitarian workers on locations Violence against humanitarian 31 workers on roads !Abeïbara ! Arawane Boujbeha! KIDAL ! Tin-Essako ! Anefif Al-Ourche! 28 ! Inékar Bourem! TIMBUKTU ! Gourma- 17 Rharous Goundam! 36 Diré! GAO 2 ! Niafunké ! Tonka ! BAMAKO Léré Gossi ! ! MÉNAKA Ansongo ! ! Youwarou! Anderamboukane Ouattagouna! Douentza ! NIGER MOPTI Ténénkou! 1 Bandiagara! 18 Koro! Bankass! SÉGOU Djenné! BURKINA FASO The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Key messages Insecurity in northern and central Mali: Both areas are experiencing an Number of access constraints unprecedented level of criminality, terrorism and armed conflict directly impeding access. 133 2017 Movement on road: Ansongo-Ménaka, Gao-Anefis-Kidal, 18 Timbuktu-Goundam, Bambara Maoudé-Timbuktu road axis are very difficult 68 2016 to navigate during the rainy season. Armed groups’presence requires 17 ongoing negotiations at different levels prior to using roads. Humanitarians are mostly victim of criminal activities on roads. 13 13 13 11 Aerial access: Existing airports allow access to regional capitals and big 11 9 9 9 cities in Bamako, Timbuktu, Gao and Mopti. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Prause, Gunnar (Ed.) Working Paper Regional networking as success factor in the transformation processes of maritime industry: Experiences and perspectives from Baltic Sea countries Wismarer Diskussionspapiere, No. 07/2010 Provided in Cooperation with: Hochschule Wismar, Wismar Business School Suggested Citation: Prause, Gunnar (Ed.) (2010) : Regional networking as success factor in the transformation processes of maritime industry: Experiences and perspectives from Baltic Sea countries, Wismarer Diskussionspapiere, No. 07/2010, ISBN 978-3-939159-89-6, Hochschule Wismar, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Wismar This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/45811 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) -

GIRLS' MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT in SCHOOLS: CASE STUDY in the NORD and EST REGIONS of BURKINA FASO, WEST AFRICA This Repor

GIRLS’ MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT IN SCHOOLS: CASE STUDY IN THE NORD AND EST REGIONS OF BURKINA FASO, WEST AFRICA This report has been written by Tidiani Ouedraogo, UNICEF consultant, with the support of Victoria Trinies, international UNICEF consultant, and research assistants Traoré Alimata, Yago Iphigénie, Pacmogda Pascaline and Sissao Inoussa. It has been prepared in close collaboration with the multisectoral working group in place, coordinated by the Directorates for Girls' Education and Gender Equality of the Ministère de l’Education Nationale et de l’Alphabétisation [Ministry of National Education and Literacy] (MENA). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank all legal entities and individuals, and all members of the monitoring committee, who have given their support in the completion of this research. This report arose from the project "WASH in Schools for Girls: Advocacy and Capacity Building for MHM through WASH in Schools Programmes" (WinS4Girls Project), funded by the Government of Canada. Our thanks to Emory University (Bethany Caruso, Anna Ellis, Gauthami Penakalapati, Gloria Sclar, Candace Girod and Matthew Freeman) for their support and guidance with the research and the drafting of the report. Grateful thanks also to the WASH programme at UNICEF headquarters (Murat Sahin, Lizette Burgers, Maria Carmelita Francois, Sue Cavill and Yodit Sheido) for their support and guidance. We would also like to highlight the leadership role played by Columbia University (Marni Sommer) and by the advisory group (United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative [UNGEI] and the UNICEF departments for gender equality, adolescent development and participation, and education). Thank you to the central administrative authorities, in particular the ministries for education — the former Ministry of National Education (MENA) and the Ministry of Secondary and Higher Education (MESS) — both to their secretary generals and to their respective Directorates for Girls' Education and Gender Equality (DEFPG). -

ADMINISTRATIVE REGULATION in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Fiutz MORSTEIN MARX*

ADMINISTRATIVE REGULATION IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE FiuTz MORSTEIN MARX* I Comparing is a means toward understanding. This being so, we may expect to enhance a proper assessment of administrative regulation by looking at the record of foreign experience. Perhaps there are lessons that deserve consideration-or cautions, or hints. Even a dull tracing of parallels may help to clarify trends and tendencies. For obvious reasons, however, comparison is most fruitful when its object does not change from place to place. To a rider, the care of his horse is likely to be of considerable concern. But he would not get much enlightenment from inquiring into the treatment of man's mount elsewhere if man's mount elsewhere happened to be an elephant, or a camel, or a burro. In its most precise meaning, perhaps, ad- ministrative regulation as talked about in the United States does pose the same problem. In certain respects, it is something peculiarly home-grown. It may be too American for comparative examination to yield a full harvest. The implications of such doubt are enlarged when one remarkable thing is borne in mind. It comes to light in the fact that the prevailing mode of reference in the United States links administrative regulation with the imposition of authority over economic interests, with the powers of government as they affect business. Administrative regulation thus is focused primarily on statutory clauses, public agencies, and official procedures, on the one hand, and on economic practices, on the other. Surprisingly little attention, by and large, has been given to the social matrix of administrative regulation, even to its basic ends. -

Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censusespdf

. ~ . DATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULA'EION . IN RECENT CENSUSES ... I UNITED NATIONS POPULATION STUDIES, No. 8 D_ATA ON URBAN AND RURAL POPULATION IN RECENT CENSUSES Department of Social Affairs Department of Economic Affairs Population Division Statistical Office of the United Nations Lake Success, New York July 1950 .... ST/ SOA/Series A. Population Studies, No. 8 List of reports in this series to date : Reports on the Population of Trust Territories No. 1. The Population of W estem Samoa No. 2. The Population of Tanganyika Reports on Popub.tion Estimates No. 3. World Population Trends, 1920-1947 Reports on Methods of Population St:atist.ics No. 4. Population Census Methods No. 6. Fertility Data in Population Censuses No. 7. Methods of Using Census Statistics for the Calculation or Life Tables and Other Demographic Measures. With Application to the Population of Brazil. By Giorgio Mortara No. 8. Data on Urban and Rural Population in Recent Censuses Report• on Demographic Aspects of Mi.gration No. 5. Problems of Migration Statistics UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS S:ales No.: 1950 • Xlll • 4 · ~ FOREWORD The Economic and Social Council, at its fourth session, adopted a resolution requesting the Secretary-General of the United Nations to offer advice and assist ance to Member States, with a view to improving the comparability and quality of data to be obtained in the censuses of 1950 and proximate years (resolution 41 (IV), 29 March 1947). As part of the implementation of this resolution, a series of studies has been prepared on the methods of obtaining and presenting information in population censuses on the size and characteristics of the population. -

The French Water and River Management System - an Overview

1 The French Water & River Management System __________________________ THE RIVER RESTORATION CENTRE CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY The French Water and River Management System - An Overview - Jeremy Watkins ENGEES – 2nd Year Student July 2012 Proofread by Simon Medaney 2 The French Water & River Management System Introduction France has an extensive river network. Wide and narrow, fast and slow, long and short, they are all important for biodiversity and the environment. There are hundreds of rivers in France flowing through the départements and régions. In fact, most of the French départements are named after the main river flowing through its territory. In France, 25 % of potable water comes from rivers, so it is important that they are properly managed, to prevent of pollution. In some areas of France, floods are part of life. In the 1960s, substantial work was done to straighten rivers and build weirs all over the country to create safe areas for new building projects. They took little account of the natural course of the rivers. Faced with the past neglect of the environment, habitats and biodiversity, the French government has chosen restoration and management strategies in order to correct the mistakes which were made and to make rivers part of the environmental heritage of the country. The strategies and objectives have been set in order to meet the Water Framework Directive’s 2015 deadline. In order to implement the strategies, in 1991 and 1992, two major parliamentary decisions were taken: the decentralization of governmental obligations and powers by creating local equivalents of the Ministry of the Environment, and the “Second Water Law”, passed in 1992. -

Applying the Degree of Urbanisation to the Globe: a New Harmonised Definition Reveals a Different Picture of Global Urbanisation

APPLYING THE DEGREE OF URBANISATION TO THE GLOBE: A NEW HARMONISED DEFINITION REVEALS A DIFFERENT PICTURE OF GLOBAL URBANISATION Lewis Dijkstra (corresponding author), Aneta Florczyk, Sergio Freire, Thomas Kemper and Martino Pesaresi Paper prepared for the 16th Conference of IAOS OECD Headquarters, Paris, France, 19-21 September 2018 Session 6.E., Day 3, 21/09, 14:00: Developing a global definition of cities and settlements for statistical purposes Lewis Dijkstra [email protected] European Commission Aneta Florczyk [email protected] European Commission Sergio Freire [email protected] European Commission Thomas Kemper [email protected] European Commission Martino Pesaresi [email protected] European Commission APPLYING THE DEGREE OF URBANISATION TO THE GLOBE: A NEW HARMONISED DEFINITION REVEALS A DIFFERENT PICTURE OF GLOBAL URBANISATION DRAFT VERSION 5/9/2018 Prepared for the 16th Conference of the International Association of Official Statisticians (IAOS) OECD Headquarters, Paris, France, 19-21 September 2018 Note: This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Commission. The views expressed are those of the author(s). ABSTRACT This article presents a new methodology, the degree of urbanisation, and its application to the globe. The degree of urbanisation relies on a population grid to classify local units into three classes: cities, towns & suburbs, and rural areas. These three classes can be further disaggregated into cities, towns, suburbs, villages, dispersed rural areas and mostly uninhabited areas. The population share in rural areas as defined by the degree of urbanisation is similar to the share reported based on national definitions in most countries in the Americas and Europe, but radically different in many African and Asian countries. -

Immigration Detention in France

COUNTRY REPORT IMMIGRATION DETENTION IN FRANCE: LONGER, MORE WIDESPREAD, AND HARDER TO CONTEST October 2018 COUNTRY REPORT IMMIGRATION DETENTION IN FRANCE: LONGER, MORE WIDESPREAD, AND HARDER TO CONTEST OCTOBER 2018 THE GLOBAL DETENTION PROJECT MISSION The Global Detention Project (GDP) is a non-profit organisation based in Geneva that promotes the human rights of people who have been detained for reasons related to their non-citizen status. Our mission is: • To promote the human rights of detained migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers; • To ensure transparency in the treatment of immigration detainees; • To reinforce advocacy aimed at reforming detention systems; • To nurture policy-relevant scholarship on the causes and consequences of migration control policies. Global Detention Project 3 rue de Varembé 1202 Geneva Switzerland Email: [email protected] Website: www.globaldetentionproject.org Front cover image: Activists from La Cimade stage a protest against France’s controversial new legislation—dubbed the Code de la honte (“code of shame”)—outside the Paris National Assembly, April 2018. © Célia Bonnin This report is also available online at www.globaldetentionproject.org CONTENTS Glossary 6 Key Concerns 7 1. Introduction 8 2. Laws, Policies, Practices 12 2.1 Key norms 12 2.2 Grounds for detention 13 2.3 Asylum seekers 13 2.4 Children 16 2.5 Other vulnerable groups 21 2.5a People with disabilities 21 2.5b Women 21 2.6 EU citizens 21 2.7 From prison to immigration detention 22 2.8 Length of detention 23 2.9 Procedural guarantees 25 2.10 Detaining authorities and institutions 26 2.11 Non-custodial measures 27 2.12 Regulation of detention conditions 29 2.13 Domestic monitoring 29 2.14 International monitoring 30 2.15 Criminalisation 32 2.16 Privatisation 33 2.17 Cost of detention 33 2.18 Externalisation, readmission, and third-country agreements 34 2.19 Transparency and access to information 34 2.20 Trends and statistics 35 2.21 The case of Mayotte 35 3.