Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized Towns in the Light of Their Constraints and Opportunities - the Case of Nevers (Burgundy - France)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

ESPON PROFECY D5 Annex 17. 10 Additional

PROFECY – Processes, Features and Cycles of Inner Peripheries in Europe (Inner Peripheries: National territories facing challenges of access to basic services of general interest) Applied Research Final Report Annex 17 Brief Overview of 10 IP Regions in Europe Version 07/12/2017 This applied research activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Paulina Tobiasz-Lis, Karolina Dmochowska-Dudek, Marcin Wójcik, University of Lodz, (Poland) Mar Ortega-Reig, Hèctor del Alcàzar, Joan Noguera, Institute for Local Development, University of Valencia (Spain) Andrew Copus, Anna Berlina, Nordregio (Sweden) Francesco Mantino, Barbara Forcina, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (Italy) Sabine Weck, Sabine Beißwenger, Nils Hans, ILS Dortmund (Germany) Gergely Tagai, Bálint Koós, Katalin Kovács, Annamária Uzzoli, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (Hungary) Thomas Dax, Ingrid Machold, Federal Institute for Less Favoured and Mountainous Areas (BABF) (Austria) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Barbara Acreman and Zaira Piazza (Italy), Eedi Sepp (Estonia), Zsolt Szokolai, European Commission. ESPON EGTC: Marjan van Herwijnen (Project Expert), Laurent Frideres (HoU E&O), Ilona Raugze (Director), Piera Petruzzi (Outreach), Johannes Kiersch (Financial Expert). Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. -

H-France Review Vol. 19 (June 2019), No. 91 Christophe Voilliot

H-France Review Volume 19 (2019) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 19 (June 2019), No. 91 Christophe Voilliot, Le Département de l'Yonne en 1848. Analyse d'une séquence électorale. Vulaines- sur-Seine, Seine-et-Marne: Éditions du Croquant, 2017. 238 pp. Maps, tables, figures, notes, and bibliography. ISBN 9-782365-121170; €20 (pb). Review by Peter McPhee, University of Melbourne. Jacques Rougerie long ago posed the question as to whether the history of France could be studied adequately through a departmental lens. His critique of departmental boundaries as often incoherent has not dissuaded local historians often motivated--as he quipped--by a love of their own department of “Cher-et-Tendre.”[1] Apart from departments with an obvious ethno- linguistic coherence (such as Corsica before its sub-division and Pyrénées-Orientales), most of the best studies have therefore been of provinces with a larger and more durable substance. Among them, some of the jewels in the crown of French historiography have been regional studies of 1848 and the Second Republic, such as those by Vigier, Lévêque and Corbin.[2] However, precisely because departments generally have both a rough geographic rationale and an intriguing diversity, they have also been the locus of superb historiography of the same period, as in the cases of the Var and Loiret. Christophe Voilliot discusses the pluses and minuses of his chosen arena of analysis, the department of Yonne in Burgundy, while conceding in the end that it worked best for him simply because he happened to be living there! Certainly, Yonne is an example of geographic diversity, 160km from northwest to southeast, its landscape contrasting from the limestone of Chablis to the wooded hills of Puisaye and Morvan and the Yonne valley, a laboratory to analyze divergent political behavior. -

Belgium Regions Programme Booklet a Europe That Matters!

A EUROPE THAT MATTERS! REPRESENTING LOCAL ACTORS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: PERCEPTIONS OF EU POLICY OBJECTIVES AND REGIONAL INFLUENCE Brendan Bartels, Solène David, Anastasia Donica, Alexis Gourdain, Diego Grippa, Daniele Ietri, Juuso Järviniemi, Théo Prestavoine A EUROPE THAT MATTERS! REPRESENTING LOCAL ACTORS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: PERCEPTIONS OF EU POLICY OBJECTIVES AND REGIONAL INFLUENCE Brendan Bartels, Solène David, Anastasia Donica, Alexis Gourdain, Diego Grippa, Daniele Ietri, Juuso Järviniemi, Théo Prestavoine CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. ANALYSIS OF THE MAIN TOPICS BY THEME 10 4. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 18 5. CONCLUSION 20 REFERENCES 22 INTERVIEWS 24 ANNEX I 27 ANNEX II 34 NOTES 42 Please cite as: Bartels, B., David, S., Donica, A., Gourdain, A., Grippa, D., Ietri, D., Järvin- iemi, J., Prestavoine, T., A Europe that Matters! Representing Local Actors in the Euro- pean Union: Perceptions of EU Policy Objectives and Regional Influence. 89 Initiative. 1.INTRODUCTION Does the European project struggle to present itself in a mea- ningful way to local communities, especially when they are far from metropolitan areas and centers of decision making? The divide between urban and non-urban areas seems to be signi- ficantly divisive in this respect. While in recent years efforts to reach out to local communities have multiplied and “periphe- ral” or “inner” areas have got more attention, much remains unknown about local communities’ perceptions, understanding and implementation of EU policies at the local level. Additional- ly, it is not clear to what extent local communities far from the main centers of decision making are able to represent themsel- ves and their policy priorities to higher levels of government. -

Trace Metals from Historical Mining Sites and Past

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Trace metals from historical mining sites and past metallurgical activity remain bioavailable to wildlife Received: 20 April 2017 Accepted: 11 December 2017 today Published: xx xx xxxx Estelle Camizuli 1,2, Renaud Scheifer3, Stéphane Garnier4, Fabrice Monna1, Rémi Losno5, Claude Gourault1, Gilles Hamm1, Caroline Lachiche1, Guillaume Delivet1, Carmela Chateau6 & Paul Alibert4 Throughout history, ancient human societies exploited mineral resources all over the world, even in areas that are now protected and considered to be relatively pristine. Here, we show that past mining still has an impact on wildlife in some French protected areas. We measured cadmium, copper, lead, and zinc concentrations in topsoils and wood mouse kidneys from sites located in the Cévennes and the Morvan. The maximum levels of metals in these topsoils are one or two orders of magnitude greater than their commonly reported mean values in European topsoils. The transfer to biota was efective, as the lead concentration (and to a lesser extent, cadmium) in wood mouse kidneys increased with soil concentration, unlike copper and zinc, providing direct evidence that lead emitted in the environment several centuries ago is still bioavailable to free-ranging mammals. The negative correlation between kidney lead concentration and animal body condition suggests that historical mining activity may continue to play a role in the complex relationships between trace metal pollution and body indices. Ancient mining sites could therefore be used to assess the long-term fate of trace metals in soils and the subsequent risks to human health and the environment. Te frst evidence of extractive metallurgy dates from the 6th millennium BC in the Near East1,2. -

General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect This Document

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) :je a'.ailzbie unj, , NASA sp )nsoish{i, .e interest of early and .vij'e dis- '1311on of Earth Resources Survey E82-10190 ;m iI tCf,,!^!iun and withc,ut Gabifity Iy use m,ae tt , ,. efi-U,4/y BUREAU DE RECHERCHES GEOLOGIOUES ET MINIERE S SERVICE GEOLOGIQUE NATIONAL t.:.,fl-ljl'1l.) Sa'A'IiAL 111t,tA1. PAJILMLIbi Nd.- ^.t.v CU y T.11uJ.1Lb 10 TdL MASSlt AL%PGhICAhi ANU '1uL• Lk;h'.1tAL EuANCF L1'1i1(,-:;'1hUL'1Ul AL j I UUY c'tnul hk--E,ott Juurb uu JE UnClss 4,e0l,.) ji4u#as t.2t Mit,i(-, L s) ES l: iiC At,'.)/Pic A,11 %j v19v SPATIAL THERMAL RADIOMETRY CONTRIBUTION TO THE MASSIF ARMOR►CAIN AND THE MASSIF CENTRAL (France) LITHO-STRUCTURAL STUDY FINAL REPORT 100 06partement carte g6ologique at g6otlogie gdn6rale R E C E W E D ,i'. -

GRECO G : Massif Central

Grande région écologique G Massif central Sarthe Loiret Yonne ANGERS Loir-et-Cher ¯ Maine-et-Loire Nièvre Indre-et- Côte-d'Or Loire NEVERS Cher Vienne CHÂTEAUROUX Saône-et- Indre Vendée Loire POITIERS MOULINS NIORT Allier Deux-Sèvres GUÉRET Creuse Charente- Maritime Loire Ain Puy-de-Dôme LIMOGES Rhône Haute- CLERMONT- FERRAND ANGOULÊME Vienne LYON Charente Isère SAINT-ÉTIENNE Corrèze TULLE Haute-Loire Gironde Dordogne Cantal LE PUY- G11 Châtaigneraie du Centre et de l'Ouest EN-VELAY VALENCE G12 Marches du Massif central AURILLAC Ardèche G13 Plateaux limousins Lot Lozère PRIVAS G21 Plateaux granitiques ouest du Massif central Lot-et- MENDE Drôme Garonne G22 Plateaux granitiques du centre Aveyron Ardèche du Massif central RODEZ Vaucluse G23 Morvan et Autunois Tarn-et- LandesG30 Massif central volcanique Garonne Gard G41 Bordure Nord-Est du Massif central AVIGNON G42 Monts du Vivarais et du Pilat Gers ALBI G50 Ségala et Châtaigneraie auvergnate NÎMES G60 Grands Causses Tarn Hérault TOULOUSE Bouches- G70 Cévennes Haute- MONTPELLIER du-Rhône G80 Haut-Languedoc et Lévézou Garonne G90 Plaines alluviales et piémonts Aude Méditerranée du Massif centralHautes- Pyrénées- Limite de départementPyrénées CARCASSONNE Atlantiques 05025 km Limite de GRECO Ariège Sources : BD CARTO® IGN, BD CARTHAGE® IGN Agences de l'Eau. Les SER de la GRECO G : Massif Central La GRECO G : Massif central est un collines, plaines et vallées, il occupe Par leur ressemblance climatique et massif hercynien de moyenne mon- environ un sixième (85 000 km²) géologique avec la Châtaigneraie tagne, culminant à 1 886 m au Puy de la superfi cie de la France et est limousine, les hauteurs de Gâtine de Sancy, aux reliefs arrondis, limité situé entièrement dans le domaine (Deux-Sèvres) y ont été rattachées, par le Bassin aquitain à l’ouest, biogéographique atlantique, en si bien que la GRECO regroupe le Bassin parisien au nord, la val- limite d’infl uences continentales à 14 sylvoécorégions (SER). -

Historical Mining and Smelting in the Vosges Mountains (France) Recorded in Two Ombrotrophic Peat Bogs

Historical mining and smelting in the Vosges Mountains (France) recorded in two ombrotrophic peat bogs B. Forel a, F. Monna a,⁎, C. Petit a, O. Bruguier b, R. Losno c, P. Fluck d, C. Begeot e, H. Richard e, V. Bichet e, C. Chateau f a Laboratoire ARTéHIS, UMR 5594 CNRS, Culture Université de Bourgogne, UFR SVTE, 6 bd Gabriel, F-21000 Dijon, France b Géosciences Montpellier, UMR 5243 CNRS, Université Montpellier 2, CC 60, Place Eugène Bataillon, F-34095 Montpellier Cedex 5, France c LISA, Universités Paris 7, Paris 12, CNRS, Faculté des Sciences, 61 av. du Gal de Gaulle F-94010 Créteil Cedex, France d CRESAT, UHA, 10 rue des frères Lumière, F-68093 Mulhouse Cedex, France e Laboratoire Chrono-Environnement, UMR 6249 CNRS, Université de Franche-Comté, UFR Sciences et Techniques, 16 route de Gray F-25030 Besançon Cedex, France f Université de Bourgogne, UFR SVTE, 6 bd Gabriel, F-21000 Dijon, France article info abstract Article history: Two peat sequences were sampled in the vicinity of the main mining districts of the Vosges Mountains: Received 19 November 2009 Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines and Plancher-les-Mines. Lead isotopic compositions and excess lead fluxes were Accepted 20 May 2010 calculated for each of these radiocarbon-dated sequences. Geochemical records are in very good agreement Available online 4 June 2010 with the mining history of the area, well known over the last millennium. Except for an anomaly corresponding to the Middle Bronze Age which has not yet been resolved, there is no clear geochemical Keywords: evidence of local metal production in the Vosges before the 10th century as excess lead deposition archived Environment Pollution between 500 BC and 500 AD is attributed to long-range transport of polluted particulate matter. -

Mapping Local Climate Zones and Their Applications in European Urban Environments: a Systematic Literature Review and Future Development Trends

International Journal of Geo-Information Review Mapping Local Climate Zones and Their Applications in European Urban Environments: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Development Trends Michal Lehnert 1 , Stevan Savi´c 2,* , Dragan Miloševi´c 2 , Jelena Dunji´c 3 and Jan Geletiˇc 4,5 1 Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Palacký University Olomouc, 771 46 Olomouc, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Climatology and Hydrology Research Centre, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovi´ca3, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] 3 Department of Geography, Tourism and Hotel Management, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovi´ca3, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] 4 Department of Complex Systems, Institute of Computer Science of the Czech Academy of Sciences, 182 07 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] 5 Global Change Research Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, 603 00 Brno, Czech Republic * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the light of climate change and burgeoning urbanization, heat loads in urban areas have emerged as serious issues, affecting the well-being of the population and the environment. In response to a pressing need for more standardised and communicable research into urban climate, the concept of local climate zones (LCZs) has been created. This concept aims to define the morphological types of (urban) surface with respect to the formation of local climatic conditions, largely thermal. Citation: Lehnert, M.; Savi´c,S.; This systematic review paper analyses studies that have applied the concept of LCZs to European Miloševi´c,D.; Dunji´c,J.; Geletiˇc,J. -

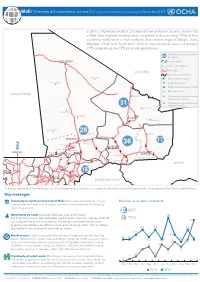

Humanitarian Access (Summary of Constraints from January to December 2017)

Mali: Overview of humanitarian access (summary of constraints from January to December 2017) In 2017, OCHA recorded 133 cases of humanitarian access constraints in Mali (the highest number ever recorded in the country). 97% of the incidents took place in the northern and central regions (Mopti, Gao, Ménaka, Kidal and Timbuktu). 41% of the incidents were robberies, 27% carjackings and 9% physical aggression. Number of access constraints xx by region TAOUDÉNIT Limit of region Limit of new regions ALGERIA Main road International boundaries Achourat! Non-functional airport Foum! Elba Functional airport Regional administrative centre ! Populated place MAURITANIA ! Téssalit Violence against humanitarian workers on locations Violence against humanitarian 31 workers on roads !Abeïbara ! Arawane Boujbeha! KIDAL ! Tin-Essako ! Anefif Al-Ourche! 28 ! Inékar Bourem! TIMBUKTU ! Gourma- 17 Rharous Goundam! 36 Diré! GAO 2 ! Niafunké ! Tonka ! BAMAKO Léré Gossi ! ! MÉNAKA Ansongo ! ! Youwarou! Anderamboukane Ouattagouna! Douentza ! NIGER MOPTI Ténénkou! 1 Bandiagara! 18 Koro! Bankass! SÉGOU Djenné! BURKINA FASO The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Key messages Insecurity in northern and central Mali: Both areas are experiencing an Number of access constraints unprecedented level of criminality, terrorism and armed conflict directly impeding access. 133 2017 Movement on road: Ansongo-Ménaka, Gao-Anefis-Kidal, 18 Timbuktu-Goundam, Bambara Maoudé-Timbuktu road axis are very difficult 68 2016 to navigate during the rainy season. Armed groups’presence requires 17 ongoing negotiations at different levels prior to using roads. Humanitarians are mostly victim of criminal activities on roads. 13 13 13 11 Aerial access: Existing airports allow access to regional capitals and big 11 9 9 9 cities in Bamako, Timbuktu, Gao and Mopti. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Prause, Gunnar (Ed.) Working Paper Regional networking as success factor in the transformation processes of maritime industry: Experiences and perspectives from Baltic Sea countries Wismarer Diskussionspapiere, No. 07/2010 Provided in Cooperation with: Hochschule Wismar, Wismar Business School Suggested Citation: Prause, Gunnar (Ed.) (2010) : Regional networking as success factor in the transformation processes of maritime industry: Experiences and perspectives from Baltic Sea countries, Wismarer Diskussionspapiere, No. 07/2010, ISBN 978-3-939159-89-6, Hochschule Wismar, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Wismar This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/45811 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) -

GIRLS' MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT in SCHOOLS: CASE STUDY in the NORD and EST REGIONS of BURKINA FASO, WEST AFRICA This Repor

GIRLS’ MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT IN SCHOOLS: CASE STUDY IN THE NORD AND EST REGIONS OF BURKINA FASO, WEST AFRICA This report has been written by Tidiani Ouedraogo, UNICEF consultant, with the support of Victoria Trinies, international UNICEF consultant, and research assistants Traoré Alimata, Yago Iphigénie, Pacmogda Pascaline and Sissao Inoussa. It has been prepared in close collaboration with the multisectoral working group in place, coordinated by the Directorates for Girls' Education and Gender Equality of the Ministère de l’Education Nationale et de l’Alphabétisation [Ministry of National Education and Literacy] (MENA). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank all legal entities and individuals, and all members of the monitoring committee, who have given their support in the completion of this research. This report arose from the project "WASH in Schools for Girls: Advocacy and Capacity Building for MHM through WASH in Schools Programmes" (WinS4Girls Project), funded by the Government of Canada. Our thanks to Emory University (Bethany Caruso, Anna Ellis, Gauthami Penakalapati, Gloria Sclar, Candace Girod and Matthew Freeman) for their support and guidance with the research and the drafting of the report. Grateful thanks also to the WASH programme at UNICEF headquarters (Murat Sahin, Lizette Burgers, Maria Carmelita Francois, Sue Cavill and Yodit Sheido) for their support and guidance. We would also like to highlight the leadership role played by Columbia University (Marni Sommer) and by the advisory group (United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative [UNGEI] and the UNICEF departments for gender equality, adolescent development and participation, and education). Thank you to the central administrative authorities, in particular the ministries for education — the former Ministry of National Education (MENA) and the Ministry of Secondary and Higher Education (MESS) — both to their secretary generals and to their respective Directorates for Girls' Education and Gender Equality (DEFPG).