Lassen National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a L I F O R N

BACKPACKER CALIFORNIA <<< WILD WEEKENDS IN YOUR BACKYARD & N E V A D A Lower Rock Creek Morris Meadow Enjoy a variety of seasons in Inyo National Forest Get an alpine fix, maybe some fish, on this Trinity Alps trek THE HIKE This downhill shuttle hike may be THE HIKE If you can’t wait for the warmup to hard on the knees, but the views of seasonal thaw high routes in the Sierras and southern change are easy on the eyes. In spring, you Cascades, this 18-mile out-and-back into the can watch the last remnants of snow give heart of the Trinity Alps Wilderness is just the way to blooming wildflowers; in fall, you can ticket. Follow the Stuart Fork Trail as it parallels see autumn colors rewind to vibrant summer the tumbling waters of Stuart Fork, winding greens as you descend 1,900 feet over 9.3 through a rocky channel beneath a dense miles. Start on the Lower Rock Creek Trail as canopy of mixed hardwoods. The river supports it drops gently from the upper trailhead, then cross the creek a healthy population of rainbow trout, so pack tackle. You’ll climb and follow its banks southeast for 2.2 miles. When you reach a gentle slope up a canyon amid black oaks, ponderosa pines, the road, hook right; follow the road briefly, then cross the creek and incense cedars, crossing several streams. After nearly 9 again and pick up the trail on its west bank. Head another 2.2 miles of forest, expansive Morris Meadow opens up at 4,400 miles south through the woods until you cross the road and feet. -

Trinity Alps Wilderness

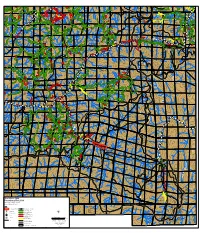

Golden ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 3 ! ! ! ! ! ! Russian ! ! ! 9 ! 6 ! 1 ! ! ! ! 7 4 ! N N ! Grizz 4 ! 4 9 0 0 0 l 3 ! 0 y 0 ! G ! 0 8 ! ! A 2 4 0 0 Lower ! N ! 0 6 0 0 0 u 0 0 4 7 ! 9 0 8 l 0 3 2 4 Lake 0 2 k ! ! 0 6 ! 4 6 2 0 r 8 N ! ! ! 0 TNH82 o ! 4 9 3 ! 36 F ! ! 00 0 3 ! ! 40 0 ! ! Russian ! 00 C 0 6 31 9 0 ! 11 ! ! 3 ! ! 2 r 0 4 0 ! 2 0 5 1 y 32 e 3 h 33 ! 3 6 7 1 5 ! 0 ! 3 5 4 0 9 0 2 34 0 ! 6 2 8 e 0 6 N ! 2 0 6 4 4 0 N ! 1 0 e ! c 0 k 0 9 ! 12 ! 0 2 6 l 4 0 Lake 4 0 10 ! ! 1 5 3 v 6 2 ! 0 Black ! N 0 9 8 ! r 3 0 0 0N83 u ! 4 0 ! 0 6 2 ! ! ! ! ! Camp Eden ! a Waterdog 5 3! ! 8 ! 5 Bear ! G ! 2 ! 1 4 ! ! !0 4 N ! 4 ! 9 9 ! ! 0 ! 3 39N40 00 H 4 W 3 6 B ! ! ! 5 C ! ! ! ! 4 0 ! ! ! Lake 39 Summit ! 0 ! ! 0 e ! ! ! ! ! 0 ! 0 C ! ! 0 ! 4 ! 0 ! 0 9:; ! ! ! 4 ! s 4 0 ! ! 4 ! ! ! 0 4 4 o ! ! A 6 ! t Russian 0 ! ! ! 0 ! ! ! ! A ! 0 ! ! ! ! ! 0 ! 6 ! ! ! ! 5 3 m ! 0 ! ! ! ! ! ! 8 ! ! ! r ! 6 0 ! ! 3 ! 0 ! 440 ! 4 ! g ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 4 ! 0 p 9 ! 4 0 ! A ! ! 0 N ! 0 3 ! ! 0 ! r u ! e ! N ! ! ! ! ! 6 Lake ! ! ! ! e ! ! e ! 0 ! 1 ! ! s ! s ! 39 ! k s 0 9 ! ! ! 12 ! ! ! 0 ! ! o ! n h ! k n ! ! o ! s 9:; ! ! ! ! ! ! k ! t ! ! r c ! a C ! ! ! F J ! r a ! ! A e ! ! e ! ! e ! ! k u ! B h ! 41N16 D ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! Y ! ! ! ! ! o ! 12 ! e E o c ! 3 ! 8 Jackson ! l ! ! r ! ! ! r 11 0 ! 7 ! e 8 9 ! S 0 0 ! 11 ! ! u 9 ! 10 k 10 2 k ! 3 3 C 7 8 0 7 v ! TH ! 4 9 ! 6 8 ! i ! ! B 15 ! B 3 ! e 0 G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 14 13 ! Siphon 0 G L Lake 9 3 ! 0 7 e ! ! 0 ! 39 ! r 4 0 ! N A ! 9 ! u ! ! 0 0 ! 600 A ! 4 G 8 ! 9:; ! N 0 2 C 1 l 4 ! 0 ! 0 c 8 ! ! 8 u Lake 5 5 6 8 5 0 L -

California Human-Black Bear Incidents (1986 - Present)

California Human-Black Bear Incidents (1986 - Present) Date Incident Type County Incident Location Victim Sex Victim Age 2015- August Nonfatal Mono Lee Vining Male 46 2015- August Nonfatal Mariposa Rural residential in Midpines Male 66 2015- July Nonfatal Placer Alpine Meadows Female unknown 2015- June Nonfatal Mono Mammoth Lakes Female unknown 2015- June Nonfatal Tulare Potwisha Campground Male 26 2015- June Nonfatal Butte Magalia Unknown unknown 2014- September Nonfatal Mono Mammoth Lakes Male Unknown 2014- June Nonfatal Placer Residential area north of Kings Beach Female 68 2014- unknown Nonfatal San Bernardino Lake Arrowhead area Female unknown 2014- unknown Nonfatal Santa Barbara unknown Female unknown 2013- May Nonfatal Fresno Lower Paradise Valley Male unknown 2013- unknown Nonfatal Ventura unknown Female unknown 2012- October Nonfatal Ventura Gridley Trail, Hermitage Ranch Private Property, Ojai Female unknown 2012- July Nonfatal Placer Homewood Male unknown 2011- June Nonfatal El Dorado Badgers Den Campground Male unknown 2010- November Nonfatal Placer Residential area, Alta Female unknown 2010- September Nonfatal Mono unknown Male unknown 2010- September Nonfatal Mono Mammoth Lakes Male unknown 2010- September Nonfatal Mariposa Yosemite National Park Male Unknown 2010- August Nonfatal El Dorado Residential area, South Lake Tahoe Male unknown 2010- August Nonfatal El Dorado Fallen Leaf Campground Male unknown 2010- July Nonfatal El Dorado Yellowjacket campground Male unknown 2010- June Nonfatal Tulare Buckeye campground Female -

Cascades Frog Conservation Assessment

D E E P R A U R T LT MENT OF AGRICU United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station Cascades Frog General Technical Report PSW-GTR-244 Conservation Assessment March 2014 Karen Pope, Catherine Brown, Marc Hayes, Gregory Green, and Diane Macfarlane The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency’s EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust. html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. You may also write a letter containing all of the information requested in the form. Send your completed complaint form or letter to us by mail at U.S. -

Guidelines for Evaluating Air Pollution Impacts on Class I Wilderness Areas in California

United States Department of Agriculture Guidelines for Evaluating Air Forest Service Pollution Impacts on Class I Pacific Southwest Research Station General Technical Wilderness Areas in California Report PSW-GTR-136 David L. Peterson Daniel L. Schmoldt Joseph M. Eilers Richard W. Fisher Robert D. Doty Peterson, David L.; Schmoldt, Daniel L.; Eilers, Joseph M.: Fisher, Richard W.; Doty, Robert D. 1992. Guidelines for evaluating air pollution impacts on class I wilderness areas in California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR- 136. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, US. Department of Agriculture; 34 p. The 1977 Clean Air Act legally mandated the prevention of significant deterioration (PSD) of air quality related values (AQRVs) on wilderness lands. Federal land managers are assigned the task of protecting these wilderness values. This report contains guidelines for determining the potential effects of incremental increases in air pollutants on natural resources in wilderness areas of the National Forests of California. These guidelines are based on current information about the effects of ozone, sulfur, and nitrogen on AQRVs. Knowledge-based methods were used to elicit these guidelines from scientists and resource managers in a workshop setting. Linkages were made between air pollutant deposition and level of deterioration of specific features (sensitive receptors) of AQRVs known to be sensitive to pollutants. Terrestrial AQRVs include a wide number of ecosystem types as well as geological and cultural values. Ozone is already high enough to injure conifers in large areas of California and is a major threat to terrestrial AQRVs. Aquatic AQRVs include lakes and streams, mostly in high elevation locations. -

Whitebark Pine Pilot Fieldwork Report Klamath National Forest

Whitebark Pine Pilot Fieldwork Report Klamath National Forest By Michael Kauffmann1, Sara Taylor2, Kendra Sikes3, and Julie Evens4 In collaboration with: Marla Knight, Forest Botanist, Klamath National Forest Diane Ikeda, Regional Botanist, Pacific Southwest Region, USDA Forest Service January, 2014 November 2018 Update: Page 47 1. Kauffmann, Michael E., Humboldt State University, Redwood Science Project, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, [email protected] 2. Taylor, Sara M., California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] 3. Sikes, Kendra., California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] 4. Evens, Julie., California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] Photo on cover page: Pinus albicaulis seen from Boulder Peak in the Marble Mountain Wilderness area, Klamath National Forest All photos by Michael Kauffmann unless otherwise noted All figures by Kendra Sikes unless otherwise noted Acknowledgements: We would like to acknowledge Marla Knight, Julie K. Nelson and Diane Ikeda for reviewing and providing feedback on this report. We also would like to thank Matt Bokach, Becky Estes, Jonathan Nesmith, Nathan Stephenson, Pete Figura, Cynthia Snyder, Danny Cluck, Marc Meyer, Silvia Haultain, Deems Burton and Peggy Moore for providing field data points or mapped whitebark pine for this project. Special thanks to Dr. Jeffrey Kane and Jay Smith for adventuring into the northern California wilds and helping with field work. Suggested report citation: Kauffmann, M., S. Taylor, K. Sikes, and J. Evens. 2014. Klamath National Forest: Whitebark Pine Pilot Fieldwork Report. Unpublished report. -

Page 1480 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1113 (Pub

§ 1113 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1480 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 13, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation § 1113. Authorization of appropriations System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- There are hereby authorized to be appro- priations be available for additional personnel priated to the Department of the Interior with- stated as being required solely for the purpose of out fiscal year limitation such sums as may be managing or administering areas solely because necessary for the purposes of this chapter and they are included within the National Wilder- the agreement with the Government of Canada ness Preservation System. signed January 22, 1964, article 11 of which pro- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined vides that the Governments of the United States A wilderness, in contrast with those areas and Canada shall share equally the costs of de- where man and his own works dominate the veloping and the annual cost of operating and landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where maintaining the Roosevelt Campobello Inter- the earth and its community of life are un- national Park. trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- (Pub. L. 88–363, § 14, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this chapter an CHAPTER 23—NATIONAL WILDERNESS area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its PRESERVATION SYSTEM primeval character and influence, without per- manent improvements or human habitation, Sec. which is protected and managed so as to pre- 1131. -

A Summer Meditation on the Meaning of Wilderness | 1

A summer meditation on the meaning of wilderness | 1 It’s outdoor weather in far northern California, my favorite place on the planet. A day hike yesterday in the beautiful Trinity Alps Wilderness reminded me of the central question of wilderness management: how much anthropogenic modification for what purposes is compatible with the wilderness experience? This hike provided two contrasting perspectives on that question. It’s just gone spring in the high country here, after an unusually snowy winter. The azaleas, lady’s slippers, and darlingtonia are just coming into bloom, snow still lingers in patches and on the peaks, and the creeks are running high, fast, and cold. We were headed up Swift Creek, which in this season fully justified its name. The trail split a little ways out, with one fork crossing this impressive bridge: We didn’t take that path, not because we were averse to crossing the bridge but because the meadows we wanted to see lay in the other direction. Had we wanted to cross Swift Creek, though, we could easily have done so at the bridge. Even people much younger and fitter than us could not have crossed safely under the current spring flow conditions (the A summer meditation on the meaning of wilderness | 2 picture doesn’t do the water levels justice) if there were no bridge. The other fork took us up through the wildflower meadows we were seeking. It required us to cross a couple of smaller tributary streams, which we did at narrow points with the help of some well-placed fallen trees. -

Shasta-Trinity National Forest Outfitter and Guide Program (2019-2028)

Shasta-Trinity National Forest Outfitter and Guide Program (2019-2028) 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................2 Background .................................................................................................................................................................2 Proposed Action (Guiding Locations for Each Activity) ..............................................................................................3 Purpose and Need ....................................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Trends .........................................................................................................................................................................9 Analysis for Capacity ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Current Resource Protection Measures/Site Specific Requirements ...................................................................... 13 Introduction and Purpose and Need Outfitter and guide services provide a great opportunity for people of all ages to get outdoors and recreate on their National Forests. The total amount of visitor days that are spent outfitting or guiding on the National Forest amounts to only a small fraction of the overall recreational use that is -

Incident Management Situation Report Friday, October 1, 1999 - 0530 Mdt National Preparedness Level Iii

INCIDENT MANAGEMENT SITUATION REPORT FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 1999 - 0530 MDT NATIONAL PREPAREDNESS LEVEL III CURRENT SITUATION: Increased initial attack activity occurred in the Southern Area, while moderate initial attack activity was reported in Southern California. Minimal initial attack activity happened elsewhere. New large fire activity was reported in the Eastern Great Basin, Rocky Mountain, Southern California, and Southern Areas. The National Interagency Coordination Center mobilized air tankers, helicopters, infrared aircraft, radio equipment, engines, meteorological equipment, crews, and miscellaneous overhead. Very high to extreme fire indices were reported in Oregon, Washington, California, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, and Colorado. NORTHERN CALIFORNIA LARGE FIRES: BIG BAR COMPLEX, Shasta-Trinity National Forest. An Area Command Team (Denton), a Type I Incident Management Team (Bateman) and a Type I Incident Management Team (Frye) are assigned. The complex is 28 miles northwest of Weaverville, CA. The complex consists of the Megram and Onion fires. The Megram fire has burned onto the Six Rivers National Forest. LITTLE, Shasta-Trinity National Forest. A Type II Incident Management Team (Feser) has transition with a Type II Incident Management Team (Ratliff). The fire is 24 miles northeast of Weaverville, CA. Current threats include the Trinity Alps Wilderness, private timber lands and harvest operations. A northerly wind event predicted for today threatens unsecured perimeter and residential structures. Crews have made good progress towards completing fireline and continue with mopup. GUN 2, Tehama-Glenn Ranger Unit, California Department of Forestry. A Unified Command with California Department of Forestry (Johnson) and the U.S. Forest Service (Madden) is in place. The fire is 20 miles east of Redding, CA. -

A Bill to Designate Certain Public Lands in the State of California As Wilderness, and for Other Purposes

98 S.5 Title: A bill to designate certain public lands in the State of California as wilderness, and for other purposes. Sponsor: Sen Cranston, Alan [CA] (introduced 1/26/1983) Cosponsors (None) Latest Major Action: 4/23/1984 Senate committee/subcommittee actions. Status: Committee on Energy and Natural Resources received executive comment from Agriculture Department. Unfavorable. SUMMARY AS OF: 1/26/1983--Introduced. California Wilderness Act of 1983 - Designates as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System the following lands in the State of California: (1) the Boundary Peak Wilderness in the Inyo National Forest; (2) the Caliente Wilderness in the Cleveland National Forest; (3) the Caples Creek Wilderness in the Eldorado National Forest; (4) the Caribou Wilderness Additions in the Lassen National Forest; (5) the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness in the Stanislaus and Toiyabe National Forests; (6) the Castle Crags Wilderness in the Shasta Trinity National Forest; (7) the Chancelulla Wilderness in the Shasta Trinity National Forest; (8) the Cinder Buttes Wilderness in the Lassen National Forest; (9) the Cucamonga Wilderness Additions in the Angeles National Forest; (10) the Deep Wells Wilderness in the Inyo National Forest; (11) the Dick Smith Wilderness in the Los Padres National Forest; (12) the Dinkey Lakes Wilderness in the Sierra National Forest; (13) the Domeland Wilderness Additions in the Sequoia National Forest; (14) the Emigrant Wilderness Additions in the Stanislaus National Forest; (15) the Excelsior Wilderness in -

Northwest California Wilderness, Recreation, and Working Forests Act

116TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 116–389 NORTHWEST CALIFORNIA WILDERNESS, RECREATION, AND WORKING FORESTS ACT FEBRUARY 4, 2020.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. GRIJALVA, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following R E P O R T together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 2250] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2250) to provide for restoration, economic development, recreation, and conservation on Federal lands in Northern Cali- fornia, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon with an amendment and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. The amendment is as follows: Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Northwest California Wilderness, Recreation, and Working Forests Act’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Definitions. TITLE I—RESTORATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Sec. 101. South Fork Trinity-Mad River Restoration Area. Sec. 102. Redwood National and State Parks restoration. Sec. 103. California Public Lands Remediation Partnership. Sec. 104. Trinity Lake visitor center. Sec. 105. Del Norte County visitor center. Sec. 106. Management plans. Sec. 107. Study; partnerships related to overnight accommodations. TITLE II—RECREATION Sec. 201. Horse Mountain Special Management Area. 99–006 VerDate Sep 11 2014 08:14 Feb 07, 2020 Jkt 099006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6659 Sfmt 6631 E:\HR\OC\HR389.XXX HR389 2 Sec.