Bigfoot Trail • V3.2017 Map Set & Trail Description Michael Kauffmann Jason Barnes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

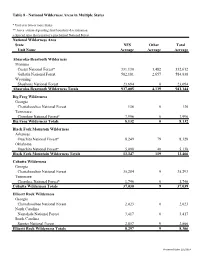

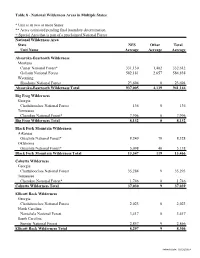

Table 8 — National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States

Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Montana Custer National Forest* 331,130 1,482 332,612 Gallatin National Forest 582,181 2,657 584,838 Wyoming Shoshone National Forest 23,694 0 23,694 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Totals 937,005 4,139 941,144 Big Frog Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 136 0 136 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 7,996 0 7,996 Big Frog Wilderness Totals 8,132 0 8,132 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Arkansas Ouachita National Forest* 8,249 79 8,328 Oklahoma Ouachita National Forest* 5,098 40 5,138 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Totals 13,347 119 13,466 Cohutta Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 35,284 9 35,293 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 1,746 0 1,746 Cohutta Wilderness Totals 37,030 9 37,039 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 2,023 0 2,023 North Carolina Nantahala National Forest 3,417 0 3,417 South Carolina Sumter National Forest 2,857 9 2,866 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Totals 8,297 9 8,306 Processed Date: 2/5/2014 Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage -

Happy Camp and Oak Knoll 2018 120318

KLAMATH NATIONAL FOREST RANGER DISTRICT SPECIFIC CUTTING CONDITIONS For woodcutting in Happy Camp, Oak Knoll, Salmon River, and Scott River listen to the West Zone KLAMATH NATIONAL FOREST OFFICES PERSONAL USE FIREWOOD CONDITIONS danger rating. For the Goosenest, listen to the East Zone. In addition to the Forest-Wide Personal Use Firewood Conditions, the following applies to woodcut- Ranger District and Supervisors Office hours are 8:00 AM - 4:30 PM. United States Department of Agriculture This map, together with the Motor Vehicle Use Map (MVUM), and fuelwood tags are ting on specific Districts of the Klamath National Forest. Woodcutters shall have an USDA, Forest Service approved spark arrester on the chainsaw and fire Forest Service a part of your woodcutting permit and must be in your possession while cutting, HAPPY CAMP extinguisher or a serviceable shovel not less than 46 inches in length within 25 feet of woodcutting area. Forest Supervisor's Office Happy Camp Ranger District gathering, and transporting your wood. 1711 South Main St. 63822 Highway 96 A. Within areas designated for General Firewood Cutting: Check woodcutting site for any smoldering fire and extinguish before leaving. Yreka, CA 96097 Happy Camp, CA 96039 In order to get the most out of your woodcutting trip, it is important that you review 1. Standing dead hardwoods and conifers may be cut. and become familiar with the terms of your Permit prior to cutting. If you have ADMINISTRATIVE REQUIREMENTS: (530) 842-6131 (530) 493-2243 2. Standing live hardwoods may be cut. (TDD) (530) 841-4573 (TDD) (530) 493-1777 questions about any terms or conditions, please contact the District you plan to visit. -

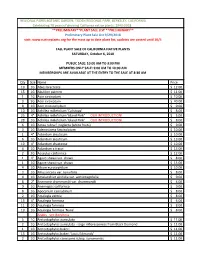

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

R-17-76 Meeting 17-15 June 28, 2017 AGENDA ITEM 15 AGENDA ITEM

R-17-76 Meeting 17-15 June 28, 2017 AGENDA ITEM 15 AGENDA ITEM Amendment to the La Honda Creek Open Space Preserve Master Plan to include One Proposed New Trail Loop and New Trail Names for the Preserve GENERAL MANAGER’S RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Approve an amendment to the La Honda Creek Open Space Preserve Master Plan to add a one-mile trail loop; 2. Approve the following trail names: “Harrington Creek Trail” for the main ranch road in lower La Honda Creek Open Space Preserve; “Folger Ranch Loop Trail” for a new loop trail off the main ranch road; “Coho Vista Trail” for the existing trail to the vista point in upper La Honda Creek; and “Cielo Trail” for an existing trail leading to the Redwood Cabin area. SUMMARY Phase I implementation of the La Honda Creek Open Space Preserve (OSP) Master Plan includes opening the Sears Ranch Road Parking Area, establishing the main Driscoll Ranch road in lower La Honda Creek as a hiking and equestrian trail, and providing permit-only equestrian parking at the former Event Center. The General Manager recommends adding an additional one-mile segment of an existing ranch road to the Phase I Trails Plan, to provide a seasonal loop opportunity, as an amendment to the Master Plan. In preparation for the opening of the Preserve, the General Manager also recommends new trail names for lower and upper La Honda Creek. The proposed trail names for lower La Honda Creek are: “Harrington Creek Trail” for the main ranch road and “Folger Ranch Trail” for the new loop. -

A Bibliography of Klamath Mountains Geology, California and Oregon

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology, California and Oregon, listing authors from Aalto to Zucca for the years 1849 to mid-1995 Compiled by William P. Irwin Menlo Park, California Open-File Report 95-558 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. PREFACE This bibliography of Klamath Mountains geology was begun, although not in a systematic or comprehensive way, when, in 1953, I was assigned the task of preparing a report on the geology and mineral resources of the drainage basins of the Trinity, Klamath, and Eel Rivers in northwestern California. During the following 40 or more years, I maintained an active interest in the Klamath Mountains region and continued to collect bibliographic references to the various reports and maps of Klamath geology that came to my attention. When I retired in 1989 and became a Geologist Emeritus with the Geological Survey, I had a large amount of bibliographic material in my files. Believing that a comprehensive bibliography of a region is a valuable research tool, I have expended substantial effort to make this bibliography of the Klamath Mountains as complete as is reasonably feasible. My aim was to include all published reports and maps that pertain primarily to the Klamath Mountains, as well as all pertinent doctoral and master's theses. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Verdura® Native Planting

Abronia maritime Abronia maritima is a species of sand verbena known by the common name red (Coastal) sand verbena. This is a beach-adapted perennial plant native to the coastlines of southern California, including the Channel Islands, and northern Baja California. Abronia villosa Abronia villosa is a species of sand-verbena known by the common name desert (Inland) sand-verbena. It is native to the deserts of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico and the southern California and Baja coast. Adenostoma Adenostoma fasciculatum (chamise or greasewood) is a flowering plant native to fasciculatum California and northern Baja California. This shrub is one of the most widespread (Coastal/Inland) plants of the chaparral biome. Adenostoma fasciculatum is an evergreen shrub growing to 4m tall, with dry-looking stick-like branches. The leaves are small, 4– 10 mm long and 1mm broad with a pointed apex, and sprout in clusters from the branches. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is a plant species of the genus Arctostaphylos (manzanita). uva-ursi Its common names include kinnikinnick and pinemat manzanita, and it is one of (Coastal/Inland) several related species referred to as bearberry. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos edmundsii, with the common name Little Sur manzanita, is a edmundsii species of manzanita. This shrub is endemic to California where it grows on the (Coastal/Inland) coastal bluffs of Monterey County. Arctostaphylos Arctostaphylos hookeri is a species of manzanita known by the common name hookeri Hooker's manzanita. Arctostaphylos hookeri is a low shrub which is variable in (Coastal/Inland) appearance and has several subspecies. The Arctostaphylos hookeri shrub is endemic to California where its native range extends from the coastal San Francisco Bay Area to the Central Coast. -

The Nikki Heat Novels by “Richard Castle”

The Nikki Heat novels by “Richard Castle” Heat Wave [2009] of their unresolved romantic conflict and crackling sexual tension fills the air as Heat and Rook embark on a search for a killer among celebrities and mobsters, singers and hookers, pro A New York real estate tycoon plunges to his athletes and shamed politicians. This new explosive case brings death on a Manhattan sidewalk. A trophy on the heat in the glittery world of secrets, cover-ups, and wife with a past survives a narrow escape scandals. from a brazen attack. Mobsters and moguls, with no shortage of reasons to kill, trot out their alibis. And then, in the suffocating grip Heat Rises [2011] of a record heat wave, comes another shocking murder and a sharp turn in a tense journey into the dirty little secrets of the The bizarre murder of a parish priest at a New wealthy. Secrets that prove to be fatal. Secrets that lay hidden York bondage house opens Nikki Heat’s most in the dark until one NYPD detective shines a light. thrilling and dangerous case so far, pitting her against New York’s most vicious drug lord, an Mystery sensation Richard Castle, blockbuster author of the arrogant CIA contractor, and a shadowy death wildly best-selling Derrick Storm novels, introduces his newest squad out to gun her down. And that is just the tip of the character, NYPD Homicide Detective Nikki Heat. Tough, sexy, iceberg that leads to a dark conspiracy reaching all the way to professional, Nikki Heat carries a passion for justice as she leads the highest level of the NYPD. -

Nature's Benefits Klamath National Forest in California

United States Department of Agriculture Nature’s Klamath National Forest In CALIFORNIA Benefits Nature’s Benefits from Your National Forests The mission of the USDA Forest Service is to livelihood—essentially Nature’s Benefits, also sustain the health, diversity, and productivity called Ecosystem Services. Benefits from of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet healthy forest ecosystems include: water the needs of present and future generations. supply, filtration and regulation (flood control); habitat for native wildlife and plants; carbon The Agency’s 154 national forests and 20 sequestration; jobs, commerce, and value to grasslands engage in quality land management local economies; recreational opportunities that offers multi-use opportunities to and open space for communities; increased meet the diverse needs of people. Forest physical and psychological wellness; cultural ecosystems are human, plant, and animal heritage; wood and other non-timber forest life-support systems that provide a suite of products; energy; clean air; and pollination. goods and services vital to human health and Do You Know Which Nature's Benefits Come from the Klamath National Forest? Water: In drought-prone California, the That equates to: quantity, quality, and timely • Over 1.5 million Olympic-size swimming provision of our water is pools dependent on the health • Enough drinking water for California’s of our national forests. The 2 forests supply, filter, and population for more than 84 years , or regulate water from upper watersheds and • Enough water for over 7.5 million meadows, providing clean water throughout households for a year3 the year to communities, homes, and wildland How much is 995 billion gallons worth? habitats. -

Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States

Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Montana Custer National Forest* 331,130 1,482 332,612 Gallatin National Forest 582,181 2,657 584,838 Wyoming Shoshone National Forest 23,694 0 23,694 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Total 937,005 4,139 941,144 Big Frog Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 136 0 136 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 7,996 0 7,996 Big Frog Wilderness Total 8,132 0 8,132 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Arkansas Ouachita National Forest* 8,249 79 8,328 Oklahoma Ouachita National Forest* 5,098 40 5,138 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Total 13,347 119 13,466 Cohutta Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 35,284 9 35,293 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 1,746 0 1,746 Cohutta Wilderness Total 37,030 9 37,039 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 2,023 0 2,023 North Carolina Nantahala National Forest 3,417 0 3,417 South Carolina Sumter National Forest 2,857 9 2,866 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Total 8,297 9 8,306 Refresh Date: 10/18/2014 Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage -

San Mateo County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of San Mateo County San Pedro San Pedro Creek flows northwesterly, entering the Pacific Ocean at Pacifica State Beach. It drains a watershed about eight square miles in area. The upper portions of the drainage contain springs (feeding the south and middle forks) that produce perennial flow in the creek. Documents with information regarding steelhead in the San Pedro Creek watershed may refer to the North Fork San Pedro Creek and the Sanchez Fork. For purposes of this report, these tributaries are considered as part of the mainstem. A 1912 letter regarding San Mateo County streams indicates that San Pedro Creek was stocked. A fishway also is noted on the creek (Smith 1912). Titus et al. (in prep.) note DFG records of steelhead spawning in the creek in 1941. In 1968, DFG staff estimated that the San Pedro Creek steelhead run consisted of 100 individuals (Wood 1968). A 1973 stream survey report notes, “Spawning habitat is a limiting factor for steelhead” (DFG 1973a, p. 2). The report called the steelhead resources of San Pedro Creek “viable and important” but cited passage at culverts, summer water diversion, and urbanization effects on the stream channel and watershed hydrology as placing “the long-term survival of the steelhead resource in question”(DFG 1973a, p. 5). The lower portions of San Pedro Creek were surveyed during the spring and summer of 1989. Three O. mykiss year classes were observed during the study throughout the lower creek. Researchers noticed “a marked exodus from the lower creek during the late summer” of yearling and age 2+ individuals, many of which showed “typical smolt characteristics” (Sullivan 1990).