Differences in Temporal and Territorial Feeding Patterns of Various Tropical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 88(1), 2013, pp. 116–126 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0276 Copyright © 2013 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala Maria E. Morales-Betoulle,† Nicholas Komar,*† Nicholas A. Panella, Danilo Alvarez, Marı´aR.Lo´pez, Jean-Luc Betoulle, Silvia M. Sosa, Marı´aL.Mu¨ ller, A. Marm Kilpatrick, Robert S. Lanciotti, Barbara W. Johnson, Ann M. Powers, Celia Cordo´ n-Rosales, and the Arbovirus Ecology Work Group‡ Center for Health Studies, Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, Guatemala; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Arbovirus Disease Branch, Fort Collins, Colorado; University of California, Santa Cruz, California; Fundacio´n Mario Dary, Guatemala City, Guatemala; and Fundacio´n para el Ecodesarrollo, Guatemala City, Guatemala Abstract. West Nile virus ecology has yet to be rigorously investigated in the Caribbean Basin. We identified a transmission focus in Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, and established systematic monitoring of avian abundance and infec- tion, seroconversions in domestic poultry, and viral infections in mosquitoes. West Nile virus transmission was detected annually between May and October from 2005 to 2008. High temperature and low rainfall enhanced the probability of chicken seroconversions, which occurred in both urban and rural sites. West Nile virus was isolated from Culex quinquefasciatus and to a lesser extent, from Culex mollis/Culex inflictus, but not from the most abundant Culex mosquito, Culex nigripalpus. A calculation that combined avian abundance, seroprevalence, and vertebrate reservoir competence suggested that great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) is the major amplifying host in this ecosystem. -

Late Breeding on the Tres Marias Islands

LATE BREEDING ON THE TRES MARfAS ISLANDS P. R. GRANT There is evidence that some passerine bird species breed later on the Tres Marias Islands than on the mainland of Mexico at the same latitude (Grant, 1964). Ob- servations on breeding activities were made on both mainland and islands in the years 1961-1963, and it was concluded that equivalent phases of the breeding season of eight species are reached from three to eight weeks later on the islands (modal value, 4 weeks) than on the mainland. These findings have been substantiated and enlarged by using other sources of data, namely references in the literature and the condition of the gonads of collected specimens (table 1). The results are as follows. Whereas at least 16 of the 19 passerine species breed later on the islands than on the mainland, according to available data, there is no clear indication that nonpasserines do so. Secondly, the breeding of most nonpasserines starts earlier in the year than does the breeding of passerines. Furthermore, at least four of the nonpasserine species have a longer breeding season than do the passerine species on both islands and mainland. The season of Amazilia rut&z (Cinnamon Hummingbird) spans 10 of the 12 months of the year ; and writing of Cyanthus Zutirostvis (Broad-billed hummingbird), Schaldach (1963) refers to specimens being in breeding condition at all seasonsof the year. The reasons for these differences are not obvious. The passerine species feed more extensively on insects than do the nonpasserines, a difference that might be correlated with the difference in time and duration of the breeding season if the pattern of available insect food is different than that of vegetable food. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13 District of Columbia, Commonwealth sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, U.S. importation of migratory birds. Virgin Islands, Guam, Commonwealth (c) What species are protected as migra- of the Northern Mariana Islands, Baker tory birds? Species protected as migra- Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, tory birds are listed in two formats to Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway suit the varying needs of the user: Al- Atoll, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, phabetically in paragraph (c)(1) of this and Wake Atoll, and any other terri- section and taxonomically in para- tory or possession under the jurisdic- graph (c)(2) of this section. Taxonomy tion of the United States. and nomenclature generally follow the Whoever means the same as person. 7th edition of the American Ornitholo- Wildlife means the same as fish or gists’ Union’s Check-list of North Amer- wildlife. ican birds (1998, as amended through 2007). For species not treated by the [38 FR 22015, Aug. 15, 1973, as amended at 42 AOU Check-list, we generally follow FR 32377, June 24, 1977; 42 FR 59358, Nov. 16, Monroe and Sibley’s A World Checklist 1977; 45 FR 56673, Aug. 25, 1980; 50 FR 52889, Dec. 26, 1985; 72 FR 48445, Aug. 23, 2007] of Birds (1993). (1) Alphabetical listing. Species are § 10.13 List of Migratory Birds. listed alphabetically by common (English) group names, with the sci- (a) Legal authority for this list. The entific name of each species following Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) in the common name. -

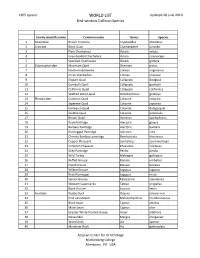

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Payne's Creek National Park Biodiversity Assessment Draft Final

Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 1 Report For: TIDE Payne’s Creek National Park Biodiversity Assessment Draft Final Report July, 2005 Wildtracks P.O. Box 278 Belize City Belize (00 501) 423-2032 [email protected] Wildtracks…2005 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 2 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park Contents Introduction page 4 1. Background 6 2. Conservation Importance of Payne’s Creek National Park 8 3. Historical Impacts that have shaped Payne’s Creek National Park 12 4. Review of Current Situation - Areas of Concern 16 5. General Field Methods 17 6. Ecosystems of Paynes Creek 18 7. Flora of Payne’s Creek 30 8. Fauna of Paynes Creek 30 8.1. Mammals 30 8.2. Birds 35 8.3 Amphibians and Reptiles 36 8.4 Fish 38 9. Conservation Planning 40 10. Management Recommendations 55 11. Biodiversity Monitoring Recommendations 56 References 61 Appendices Appendix One: Plant Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Two: Mammal Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Three: Bird Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Four: Amphibian and Reptile Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Five: Fish Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Wildtracks…2005 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 3 Maps page Map 1 Local, national and regional location of Payne’s Creek National Park 6 Map 2 Protected areas of the MMMAT 8 Map 3 Major Creeks of PCNP 9 Map 4 Hurricane Damage within Payne’s Creek 13 Map 5 Ecosystems -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

Our "High Island Migration Short"

GUATEMALA: Land of the Quetzal A Tropical Birding custom tour 17–30 Mar 2011 Leader: Michael Retter Photos by Michael Retter For such a tiny country, Guatemala has a lot to offer. The birds are diverse and colorful: Pink-headed Warbler, Blue-throated Motmot, Spot-breasted Oriole, Garnet-throated Hummingbird. With the exception of Tikal, this custom tour visited the same locations as our new set-departure, offing a wide range of habitats: cool high-elevation pine forest, a spectacular volcanic lake, dry thornscrub, lowland rainforest, and cloudforest. Though many of Guatemala’s endemic birds are shared with Mexico, here they’re easier to find and to get to. Cabanis’s (Azure-rumped) Tanager, for instance, is readily found via short ride in a vehicle just above a comfortable lodge—a far cry from the 25+ miles of hiking necessary in Mexico! And need I even mention the emerald-and-red Resplendent Quetzal (above right)? The quetzal is even the unit of currency in Guatemala. Could there possibly be a better place to see it? Itinerary 17 Mar Arrival in Guatemala City. 18 Apr Rincón Suizo to Unicornio Azul. 19 Apr Unicornio Azul. 20 Apr Fuentes Georginas and Las Nubes. 21 Apr Las Nubes. 22 Apr Las Nubes. 23 Apr Las Nubes to Los Andes. 24 Apr Los Andes to Tarrales. 25 Apr Tarrales. 26 Apr Tarrales to Panajachel via Lake Atitlán. 27 Apr Volcán San Pedro to Antigua via Panajachel. 28 Apr Finca Filadelfia. 29 Apr El Pilar. 30 Apr Departure. GUATEMALA 17–30 April 2011 - 1 - PHOTO JOURNAL Pink-headed Warblers are fairly common at higher elevations in Guatemala. -

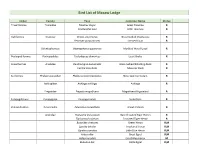

Bird List of Macaw Lodge

Bird List of Macaw Lodge Order Family Taxa Common Name Status Tinamiformes Tnamidae Tinamus major Great Tinamou R Crypturellus soul Little Tinamou R Galliformes Cracidae Ortalis cinereiceps Gray-headed Chachalaca R Penelope purpurascens Crested Guan R Odontophoridae Odontophorus gujanensis Marbled Wood-Quail R Podicipediformes Podicipedidae Tachybaptus dominicus Least Grebe R Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck R Cairina moschata Muscovy Duck R Suliformes Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax brasilianus Neotropic Cormorant R Anhingidae Anhinga anhinga Anhinga R Fregatidae Fregata magnificens Magnificent Frigatebird R Eurypygiformes Eurypygidae Eurypyga helias Sunbittern R Pelecaniformes Pelecanidae Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican R Ardeidae Tigrisoma mexicanum Bare-throated Tiger-Heron R Tigrisoma fasciatum Fasciated Tiger-Heron R Butorides virescens Green Heron R,M Egretta tricolor Tricolored Heron R,M Egretta caerulea Little Blue Heron R,M Ardea alba Great Egret R,M Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron M Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret R,M Egretta thula Snowy Egret R,M Nyctanassa violacea Yellow-crowned Night-Heron R,M Cochlearius cochlearius Boat-billed Heron R Threskiornithidae Eudocimus albus White Ibis R Mesembrinibis cayennensis Green Ibis R Platalea ajaja Roseate Sponbill R Charadriiformes Charadriidae Vanellus chilensis Southern Lapwing R Charadrius semipalmatus Semipalmated Plover M Recurvirostridae Himantopus mexicanus Black-necked Stilt R,M Scolopacidae Tringa semipalmata Willet M Tringa solitaria -

Title 50 Wildlife and Fisheries Parts 1 to 16

Title 50 Wildlife and Fisheries Parts 1 to 16 Revised as of October 1, 2018 Containing a codification of documents of general applicability and future effect As of October 1, 2018 Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register VerDate Sep<11>2014 08:08 Nov 27, 2018 Jkt 244234 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\244234.XXX 244234 rmajette on DSKBCKNHB2PROD with CFR U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The seal of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) authenticates the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as the official codification of Federal regulations established under the Federal Register Act. Under the provisions of 44 U.S.C. 1507, the contents of the CFR, a special edition of the Federal Register, shall be judicially noticed. The CFR is prima facie evidence of the origi- nal documents published in the Federal Register (44 U.S.C. 1510). It is prohibited to use NARA’s official seal and the stylized Code of Federal Regulations logo on any republication of this material without the express, written permission of the Archivist of the United States or the Archivist’s designee. Any person using NARA’s official seals and logos in a manner inconsistent with the provisions of 36 CFR part 1200 is subject to the penalties specified in 18 U.S.C. 506, 701, and 1017. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. -

Oaxaca: Birding the Heart of Mexico, March 2019

Tropical Birding - Trip Report Oaxaca: Birding the Heart of Mexico, March 2019 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Oaxaca: Birding the Heart of Mexico 6 – 16 March 2019 Isthmus Extension 16 – 22 March 2019 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report by Nick Athanas; photos are Nick’s unless marked otherwise Warblers were plentiful on this tour, such as the superb endemic Red Warbler March in much of the Northern Hemisphere was rather dreary, but in southern Mexico we enjoyed day after day of warm, sunny days and cool, pleasant evenings – it was a wonderful and bird-filled reprieve from winter for the whole group including me. The tour visited the dry Oaxaca Valley (rich in culture as well as endemics), the high mountains surrounding it, lush cloudforest and rainforest on the Gulf slope, and dry forest along the Pacific. This provided a great cross-section of the habitats and offered fantastic birds everywhere. Some favorites included Bumblebee Hummingbird, Dwarf Jay, Orange-breasted Bunting, and a daily fix of warblers, both resident and migrant, like the unique Red Warbler shown above. The extension took us east across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which serves as a natural species barrier. Numerous different species entertained us like Pink-headed Warbler, Rose-bellied Bunting, and a Nava’s Wren which put on an especially magnificent performance. Owling was a mixed bag, but our first attempt got us a spectacular Fulvous Owl, which was high up on the list of tour favorites. On tours like this, the group largely determines the success of the trip, and www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report Oaxaca: Birding the Heart of Mexico, March 2019 once again we had a friendly and pleasant set of folks who were a pleasure to travel with. -

Colibríes De México Y Norteamérica

María del Coro Arizmendi y Humberto Berlanga con ilustraciones de Marco Antonio Pineda María del Coro Arizmendi Arriaga Doctora en Ecología egresada de la UNAM. Colibríes Ornitóloga con especialidad en el estudio de de México y Norteamérica la ecología de las aves, la interacción de las aves con las plantas y la conservación de las aves. Profesora de tiempo completo denitiva en la Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, UNAM. Ha publicado 40 artículos indizados internacionales, cuatro libros y ha dirigido el trabajo de tesis de 31 estudiantes de licenciatura, 15 de maestría y dos de doctorado. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores obteniendo el nivel II en 2009. Es el punto focal de México en la iniciativa para la conservación de los polinizadores (NAPPC por sus siglas en inglés). Es parte del comité directivo del Western Hummingbird Partnership y de Hummingbird Monitoring Network. Forma parte del comité consultivo de NABCI desde 1999 participando en el comité nacional y en el trinacional. Coordinó en sus inicios el programa de Áreas de Importancia para la Conservación de las Aves en México (AICAS) publicando el directorio nacional en el año 2000. Actualmente es coordinadora del Posgrado Hummingbirds en Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM. of Mexico and North America Colibríes de México y Norteamérica Hummingbirds of Mexico and North America María del Coro Arizmendi y Humberto Berlanga con ilustraciones de Marco Antonio Pineda Primera edición, marzo 2014 D.R. © 2014, Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) Liga Periférico-Insurgentes Sur 4903, Parques del Pedregal Tlalpan, 14010 México, D.F. www.conabio.gob.mx / www.biodiversidad.gob.mx Forma de citar: Arizmendi, M.C. -

SPECIES ID NAME GEN SPEC ELEMENT SUBELEMENT GRANK GRANKDATE 386 Accipiter Hawks Accipiter Spp

SPECIES_ID NAME GEN_SPEC ELEMENT SUBELEMENT GRANK GRANKDATE 386 Accipiter hawks Accipiter spp. BIRD raptor 0 259 Alameda song sparrow Melospiza melodia pusillula BIRD passerine 0 1036 Albatrosses Phoebastria spp. BIRD pelagic 0 1024 Alcids BIRD alcid 0 215 Aleutian Canada goose Branta canadensis leucopareia BIRD waterfowl 0 101 Aleutian tern Sterna aleutica BIRD gull_tern G4 200412 575 Altamira oriole Icterus gularis BIRD passerine G5 200412 323 Amazon kingfisher Chloroceryle amazona BIRD passerine 0 141 American avocet Recurvirostra americana BIRD shorebird G5 200412 185 American bittern Botaurus lentiginosus BIRD wading G4 200412 186 American black duck Anas rubripes BIRD waterfowl G5 200412 34 American coot Fulica americana BIRD waterfowl G5 200412 746 American crow Corvus brachyrhynchos BIRD passerine G5 200412 815 American dipper Cinclus mexicanus BIRD passerine 0 164 American golden-plover Pluvialis dominica BIRD shorebird G5 200412 748 American goldfinch Carduelis tristis BIRD passerine G5 200412 182 American kestrel Falco sparverius BIRD raptor G5 200412 152 American oystercatcher Haematopus palliatus BIRD shorebird G5 200412 626 American peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus anatum BIRD raptor 0 749 American pipit Anthus rubescens BIRD passerine G5 200412 322 American pygmy kingfisher Chloroceryle aenea BIRD passerine 0 584 American redstart Setophaga ruticilla BIRD passerine G5 200412 750 American robin Turdus migratorius BIRD passerine G5 200412 173 American white pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos BIRD diving G3 200412 169 American