Management Effects on Hummingbird Abundance and Ecosystem Services in a Coffee Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centro Agronómico Tropical De Investigación Y Enseñanza Escuela De Posgrado

CENTRO AGRONÓMICO TROPICAL DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y ENSEÑANZA ESCUELA DE POSGRADO Impacto potencial del cambio climático en bosques de un gradiente altitudinal a través de rasgos funcionales por: Eugenia Catalina Ruiz Osorio Tesis sometida a consideración de la Escuela de Posgrado como requisito para optar por el grado de Magister Scientiae en Manejo y Conservación de Bosques Tropicales y Biodiversidad Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2013 I DEDICATORIA § A Juan Carlos Restrepo Arismendi § II AGRADECIMIENTOS A la Organización Internacional de Maderas Tropicales (OIMT) y el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) a través del proyecto CLIMIFORAD por el apoyo económico. A los miembros del comité especialmente a Bryan por creer en mí, Sergio por la paciencia, Diego por ser pura vida y Nelson por las asesorías botánicas. A los ayudantes de campo Vicente Herra, Leo Coto, Leo Jimenez y Mariela Saballos, por hacer de mi trabajo el de ustedes y alivianar las labores de campo. A Gloria y Jorge de la Reserva Biológica El Copal, a los guardaparques Merryl, Alexis, Leo, Juan y Agüero del Parque Nacional Tapantí-Macizo de la Muerte; Deiver, Giovany, Oscar y Carlos del Parque Nacional Barbilla. A la gran familia de Villa Mills: Marvin, Norma, Randal, Gallo y Belman. A los que me ayudaron a medir las hojas: Manuel, Cami, Julián, Jose Luis, Álvaro, Karime, Di, Juliano, Amilkar y Rebeca. A Manuel, Fabi, Jose y Dario por su solidaridad y compañía. A Zamora, Cristian y Nata por los mapas. A Fernando Casanoves por las contribuciones en la tesis A mi familia y mis amigos en CATIE Las personas crecen a través de la gente, si estamos en buena compañía es más agradable. -

West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 88(1), 2013, pp. 116–126 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0276 Copyright © 2013 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala Maria E. Morales-Betoulle,† Nicholas Komar,*† Nicholas A. Panella, Danilo Alvarez, Marı´aR.Lo´pez, Jean-Luc Betoulle, Silvia M. Sosa, Marı´aL.Mu¨ ller, A. Marm Kilpatrick, Robert S. Lanciotti, Barbara W. Johnson, Ann M. Powers, Celia Cordo´ n-Rosales, and the Arbovirus Ecology Work Group‡ Center for Health Studies, Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, Guatemala; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Arbovirus Disease Branch, Fort Collins, Colorado; University of California, Santa Cruz, California; Fundacio´n Mario Dary, Guatemala City, Guatemala; and Fundacio´n para el Ecodesarrollo, Guatemala City, Guatemala Abstract. West Nile virus ecology has yet to be rigorously investigated in the Caribbean Basin. We identified a transmission focus in Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, and established systematic monitoring of avian abundance and infec- tion, seroconversions in domestic poultry, and viral infections in mosquitoes. West Nile virus transmission was detected annually between May and October from 2005 to 2008. High temperature and low rainfall enhanced the probability of chicken seroconversions, which occurred in both urban and rural sites. West Nile virus was isolated from Culex quinquefasciatus and to a lesser extent, from Culex mollis/Culex inflictus, but not from the most abundant Culex mosquito, Culex nigripalpus. A calculation that combined avian abundance, seroprevalence, and vertebrate reservoir competence suggested that great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) is the major amplifying host in this ecosystem. -

Differences in Temporal and Territorial Feeding Patterns of Various Tropical

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2018 Differences in temporal and territorial feeding patterns of various tropical Trochilidae species as observed at two different ecosystems in Soberanía National Park Delaney Vorwick SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Poultry or Avian Science Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Vorwick, Delaney, "Differences in temporal and territorial feeding patterns of various tropical Trochilidae species as observed at two different ecosystems in Soberanía National Park" (2018). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2944. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2944 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Differences in temporal and territorial feeding patterns of various tropical Trochilidae species as observed at two different ecosystems in Soberanía National Park Delaney Vorwick Boston College Advised by Chelina Batista In conjunction with SIT Panama Fall 2018 To be reviewed by Aly Dagang Abstract This study aims to illustrate differences in feeding patterns and displays of territorialism at two artificial feeding sites, located in two ecosystems; one site in a secondary forest of Soberanía National Park, the other in a residential area in the nearby town of Gamboa. Four 1-hour observation periods were recorded each day for four days at both sites. -

Tree and Tree-Like Species of Mexico: Asteraceae, Leguminosae, and Rubiaceae

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84: 439-470, 2013 Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84: 439-470, 2013 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32013 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.32013439 Tree and tree-like species of Mexico: Asteraceae, Leguminosae, and Rubiaceae Especies arbóreas y arborescentes de México: Asteraceae, Leguminosae y Rubiaceae Martin Ricker , Héctor M. Hernández, Mario Sousa and Helga Ochoterena Herbario Nacional de México, Departamento de Botánica, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70- 233, 04510 México D. F., Mexico. [email protected] Abstract. Trees or tree-like plants are defined here broadly as perennial, self-supporting plants with a total height of at least 5 m (without ascending leaves or inflorescences), and with one or several erect stems with a diameter of at least 10 cm. We continue our compilation of an updated list of all native Mexican tree species with the dicotyledonous families Asteraceae (36 species, 39% endemic), Leguminosae with its 3 subfamilies (449 species, 41% endemic), and Rubiaceae (134 species, 24% endemic). The tallest tree species reach 20 m in the Asteraceae, 70 m in the Leguminosae, and also 70 m in the Rubiaceae. The species-richest genus is Lonchocarpus with 67 tree species in Mexico. Three legume genera are endemic to Mexico (Conzattia, Hesperothamnus, and Heteroflorum). The appendix lists all species, including their original publication, references of taxonomic revisions, existence of subspecies or varieties, maximum height in Mexico, and endemism status. Key words: biodiversity, flora, tree definition. Resumen. Las plantas arbóreas o arborescentes se definen aquí en un sentido amplio como plantas perennes que se pueden sostener por sí solas, con una altura total de al menos 5 m (sin considerar hojas o inflorescencias ascendentes) y con uno o varios tallos erectos de un diámetro de al menos 10 cm. -

Late Breeding on the Tres Marias Islands

LATE BREEDING ON THE TRES MARfAS ISLANDS P. R. GRANT There is evidence that some passerine bird species breed later on the Tres Marias Islands than on the mainland of Mexico at the same latitude (Grant, 1964). Ob- servations on breeding activities were made on both mainland and islands in the years 1961-1963, and it was concluded that equivalent phases of the breeding season of eight species are reached from three to eight weeks later on the islands (modal value, 4 weeks) than on the mainland. These findings have been substantiated and enlarged by using other sources of data, namely references in the literature and the condition of the gonads of collected specimens (table 1). The results are as follows. Whereas at least 16 of the 19 passerine species breed later on the islands than on the mainland, according to available data, there is no clear indication that nonpasserines do so. Secondly, the breeding of most nonpasserines starts earlier in the year than does the breeding of passerines. Furthermore, at least four of the nonpasserine species have a longer breeding season than do the passerine species on both islands and mainland. The season of Amazilia rut&z (Cinnamon Hummingbird) spans 10 of the 12 months of the year ; and writing of Cyanthus Zutirostvis (Broad-billed hummingbird), Schaldach (1963) refers to specimens being in breeding condition at all seasonsof the year. The reasons for these differences are not obvious. The passerine species feed more extensively on insects than do the nonpasserines, a difference that might be correlated with the difference in time and duration of the breeding season if the pattern of available insect food is different than that of vegetable food. -

Redalyc.INVENTARIO FLORÍSTICO DEL PARQUE NACIONAL CAÑÓN

Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México ISSN: 0366-2128 [email protected] Sociedad Botánica de México México ESPINOSA-JIMÉNEZ, JOSEFA ANAHÍ; PÉREZ-FARRERA, MIGUEL ÁNGEL; MARTÍNEZ-CAMILO, RUBÉN INVENTARIO FLORÍSTICO DEL PARQUE NACIONAL CAÑÓN DEL SUMIDERO, CHIAPAS, MÉXICO Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, núm. 89, diciembre, 2011, pp. 37-82 Sociedad Botánica de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57721249004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Bol.Soc.Bot.Méx. 89: 37-82 (2011) TAXONOMÍA Y FLORÍSTICA INVENTARIO FLORÍSTICO DEL PARQUE NACIONAL CAÑÓN DEL SUMIDERO, CHIAPAS, MÉXICO JOSEFA ANAHÍ ESPINOSA-JIMÉNEZ1, MIGUEL ÁNGEL PÉREZ-FARRERA Y RUBÉN MARTÍNEZ-CAMILO Herbario Eizi Matuda, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas 1Autor para la correspondencia: [email protected] Resumen: Se realizó el inventario florístico del Parque Nacional Cañón del Sumidero, Chiapas, México. Treinta y tres salidas de campo se hicieron de 2007 a 2008 y se consultaron y revisaron bases de datos de herbarios. Se registraron 1,298 especies, 632 géneros, 135 familias y 58 infraespecies. Las familias más representativas corresponden a Fabaceae (126 especies y 52 géneros) y Asteraceae (107 especies y 65 géneros). Los géneros más diversos fueron Ipomoea (18), Tillandsia (17) y Peperomia (16). Además, 625 especies se clasificaron como hierbas y 1,179 especies como autótrofas. -

Recommendation of Native Species for the Reforestation of Degraded Land Using Live Staking in Antioquia and Caldas’ Departments (Colombia)

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA Department of Land, Environment Agriculture and Forestry Second Cycle Degree (MSc) in Forest Science Recommendation of native species for the reforestation of degraded land using live staking in Antioquia and Caldas’ Departments (Colombia) Supervisor Prof. Lorenzo Marini Co-supervisor Prof. Jaime Polanía Vorenberg Submitted by Alicia Pardo Moy Student N. 1218558 2019/2020 Summary Although Colombia is one of the countries with the greatest biodiversity in the world, it has many degraded areas due to agricultural and mining practices that have been carried out in recent decades. The high Andean forests are especially vulnerable to this type of soil erosion. The corporate purpose of ‘Reforestadora El Guásimo S.A.S.’ is to use wood from its plantations, but it also follows the parameters of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). For this reason, it carries out reforestation activities and programs and, very particularly, it is interested in carrying out ecological restoration processes in some critical sites. The study area is located between 2000 and 2750 masl and is considered a low Andean humid forest (bmh-MB). The average annual precipitation rate is 2057 mm and the average temperature is around 11 ºC. The soil has a sandy loam texture with low pH, which limits the amount of nutrients it can absorb. FAO (2014) suggests that around 10 genera are enough for a proper restoration. After a bibliographic revision, the genera chosen were Alchornea, Billia, Ficus, Inga, Meriania, Miconia, Ocotea, Protium, Prunus, Psidium, Symplocos, Tibouchina, and Weinmannia. Two inventories from 2013 and 2019, helped to determine different biodiversity indexes to check the survival of different species and to suggest the adequate characteristics of the individuals for a successful vegetative stakes reforestation. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13 District of Columbia, Commonwealth sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, U.S. importation of migratory birds. Virgin Islands, Guam, Commonwealth (c) What species are protected as migra- of the Northern Mariana Islands, Baker tory birds? Species protected as migra- Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, tory birds are listed in two formats to Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway suit the varying needs of the user: Al- Atoll, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, phabetically in paragraph (c)(1) of this and Wake Atoll, and any other terri- section and taxonomically in para- tory or possession under the jurisdic- graph (c)(2) of this section. Taxonomy tion of the United States. and nomenclature generally follow the Whoever means the same as person. 7th edition of the American Ornitholo- Wildlife means the same as fish or gists’ Union’s Check-list of North Amer- wildlife. ican birds (1998, as amended through 2007). For species not treated by the [38 FR 22015, Aug. 15, 1973, as amended at 42 AOU Check-list, we generally follow FR 32377, June 24, 1977; 42 FR 59358, Nov. 16, Monroe and Sibley’s A World Checklist 1977; 45 FR 56673, Aug. 25, 1980; 50 FR 52889, Dec. 26, 1985; 72 FR 48445, Aug. 23, 2007] of Birds (1993). (1) Alphabetical listing. Species are § 10.13 List of Migratory Birds. listed alphabetically by common (English) group names, with the sci- (a) Legal authority for this list. The entific name of each species following Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) in the common name. -

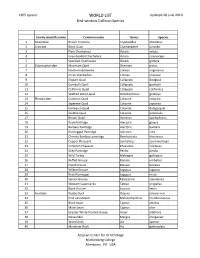

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Arboreal Ant Abundance and Leaf Miner Damage in Coffee Agroecosystems in Mexico

THE JOURNAL OF TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION BIOTROPICA 40(6): 742–746 2008 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2008.00444.x Arboreal Ant Abundance and Leaf Miner Damage in Coffee Agroecosystems in Mexico Aldo De la Mora El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Carretera Antiguo Aeropuerto Km 2.5, Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico George Livingston Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 430 N. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. and Stacy M. Philpott Department of Environmental Sciences, 2801 W. Bancroft St., University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Shaded coffee agroecosystems traditionally have few pest problems potentially due to higher abundance and diversity of predators of herbivores. However, with coffee intensification (e.g., shade tree removal or pruning), some pest problems increase. For example, coffee leaf miner outbreaks have been linked to more intensive management and increased use of agrochemicals. Parasitic wasps control the coffee leaf miner, but few studies have examined the role of predators, such as ants, that are abundant and diverse in coffee plantations. Here, we examine linkages between arboreal ant communities and coffee leaf miner incidence in a coffee plantation in Mexico. We examined relationships between incidence and severity of leaf miner attack and: (1) variation in canopy cover, tree density, tree diversity, and relative abundance of Inga spp. shade trees; (2) presence of Azteca instabilis, an arboreal canopy dominant ant; and (3) the number of arboreal twig-nesting ant species and nests in coffee plants. Differences in vegetation characteristics in study plots did not correlate with leaf miner damage perhaps because environmental factors act on pest populations at a larger spatial scale. -

Payne's Creek National Park Biodiversity Assessment Draft Final

Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 1 Report For: TIDE Payne’s Creek National Park Biodiversity Assessment Draft Final Report July, 2005 Wildtracks P.O. Box 278 Belize City Belize (00 501) 423-2032 [email protected] Wildtracks…2005 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 2 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park Contents Introduction page 4 1. Background 6 2. Conservation Importance of Payne’s Creek National Park 8 3. Historical Impacts that have shaped Payne’s Creek National Park 12 4. Review of Current Situation - Areas of Concern 16 5. General Field Methods 17 6. Ecosystems of Paynes Creek 18 7. Flora of Payne’s Creek 30 8. Fauna of Paynes Creek 30 8.1. Mammals 30 8.2. Birds 35 8.3 Amphibians and Reptiles 36 8.4 Fish 38 9. Conservation Planning 40 10. Management Recommendations 55 11. Biodiversity Monitoring Recommendations 56 References 61 Appendices Appendix One: Plant Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Two: Mammal Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Three: Bird Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Four: Amphibian and Reptile Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Appendix Five: Fish Species of Payne’s Creek National Park Wildtracks…2005 Biodiversity Assessment of Payne’s Creek National Park…. Final Report 3 Maps page Map 1 Local, national and regional location of Payne’s Creek National Park 6 Map 2 Protected areas of the MMMAT 8 Map 3 Major Creeks of PCNP 9 Map 4 Hurricane Damage within Payne’s Creek 13 Map 5 Ecosystems -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet