An Interview with Michael Berridge, Eminent Scientist in Calcium Signaling, by Ernesto Carafoli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A REVOLUTION in the PHYSIOLOGY of the LIVING CELL FUTURE ANNUAL MEETINGS of by Gilbert N

A REVOLUTION IN THE PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LIVING CELL FUTURE ANNUAL MEETINGS OF by Gilbert N. Ling Orig. Ed. 1992 404 pp. $64.50 THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR ISBN 0-89464-398-3 CELL BIOLOGY The essence of a major revolution in cell physiology -the first since the cell was recognized as the basic unit of life a century and a half ago - is presented and altemative theories are discussed in this text. Although the conventional mem- brane-pump theory is still being taught, a new theory of the living cell, called the association-induction hypothesis has been proposed. It has successfullywfthstood 1995 twenty-five years of worldwide testing and has already generated an enhancing DC diagnostic tool ofgreat power, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).This volume is Washington, intended forteachers, students and researchers ofbiology and medicine. December 9-13 i't...a correct basic theory of cell physiology, besides its great intrinsic value in mankind's search forknowledge aboutourselves and the world we live in, willalso play a crucial role in the ultimate conquest of cancer, AIDS, and other incurable 1996 diseases.'-from the Introduction. ASCB Annual Meeting/ on Cell Biology t When ordering please add t".Ling turns cellphysiology upside down. He Sixth International Congress $5.00 first bookl$1.50 each ad- practicallyredefines the cell. He provides com- San Francisco, California ditional book to cover shipping pellingevidencefor headequacyofhis theoryn December 7-11 charges. Foreign shipping costs evidence that cannot fail to impress even the available upon request. most extreme skeptics....'- Gerald H. Pollock, _ Ph.D., Univ. ofWashington. -

Biologie Moléculaire De LA CELLULE Biologie Moléculaire De Sixième Édition

Sixième édition BRUCE ALEXANDER JULIAN DAVID MARTIN KEITH PETER ALBERTS JOHNSON LEWIS MORGAN RAFF ROBERTS WALTER Biologie moléculaire de LA CELLULE Biologie moléculaire de Sixième édition LA CELLULESixième édition Biologie moléculaire de moléculaire Biologie LA CELLULE LA BRUCE ALBERTS BRUCE ALBERTS ALEXANDER JOHNSON ALEXANDER JOHNSON JULIAN LEWIS JULIAN LEWIS DAVID MORGAN DAVID MORGAN MARTIN RAFF MARTIN RAFF KEITH ROBERTS KEITH ROBERTS PETER WALTER PETER WALTER -:HSMCPH=WU[\]\: editions.lavoisier.fr 978-2-257-20678-7 20678-Albers2017.indd 1-3 08/09/2017 11:09 Chez le même éditeur Culture de cellules animales, 3e édition, par G. Barlovatz-Meimon et X. Ronot Biochimie, 7e édition, par J. M. Berg, J. L. Tymoczko, L. Stryer L’essentiel de la biologie cellulaire, 3e édition, par B. Alberts, D. Bray, K. Hopkin, A. Johnson, A. J. Lewis, M. Ra", K. Roberts et P. Walter Immunologie, par L. Chatenoud et J.-F. Bach Génétique moléculaire humaine, 4e édition, par T. Strachan et A. Read Manuel de poche de biologie cellulaire, par H. Plattner et J. Hentschel Manuel de poche de microbiologie médicale, par F. H. Kayser, E. C. Böttger, P. Deplazes, O. Haller, A. Roers Atlas de poche de génétique, par E. Passarge Atlas de poche de biotechnologie et de génie génétique, par R.D. Schmid Les biosimilaires, par J.-L. Prugnaud et J.-H. Trouvin Bio-informatique moléculaire : une approche algorithmique (Coll. IRIS), par P. A. Pevzner et N. Puech Cycle cellulaire et cytométrie en "ux, par D. Grunwald, J.-F. Mayol et X. Ronot La cytométrie en "ux, par X. Ronot, D. -

Communicating Biochemistry: Meetings and Events

© The Authors. Volume compilation © 2011 Portland Press Limited Chapter 3 Communicating Biochemistry: Meetings and Events Ian Dransfield and Brian Beechey Scientific conferences organized by the Biochemical Society represent a key facet of activity throughout the Society’s history and remain central to the present mission of promoting the advancement of molecular biosciences. Importantly, scientific conferences are an important means of communicating research findings, establishing collaborations and, critically, a means of cementing the community of biochemical scientists together. However, in the past 25 years, we have seen major changes to the way in which science is communicated and also in the way that scientists interact and establish collabo- rations. For example, the ability to show videos, “fly through” molecular structures or show time-lapse or real-time movies of molecular events within cells has had a very positive impact on conveying difficult concepts in presentations. However, increased pressures on researchers to obtain/maintain funding can mean that there is a general reluctance to present novel, unpublished data. In addition, the development of email and electronic access to scientific journals has dramatically altered the potential for communi- cation and accessibility of information, perhaps reducing the necessity of attending meetings to make new contacts and to hear exciting new science. The Biochemical Society has responded to these challenges by progressive development of the meetings format to better match the -

Research Organizations and Major Discoveries in Twentieth-Century Science: a Case Study of Excellence in Biomedical Research Hollingsworth, J

www.ssoar.info Research organizations and major discoveries in twentieth-century science: a case study of excellence in biomedical research Hollingsworth, J. Rogers Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: SSG Sozialwissenschaften, USB Köln Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hollingsworth, J. R. (2002). Research organizations and major discoveries in twentieth-century science: a case study of excellence in biomedical research. (Papers / Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, 02-003). Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung gGmbH. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-112976 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed -

Physiology News

PHYSIOLOGY NEWS summer 2009 I number 75 Calcium signalling insights from Sir Michael Berridge Physiology 2009 – back at UCD after an 18 year break Conference networking leads to post-doc position on a Japanese tropical island PowerLab : buy or rent Easy to use, easy to acquire PowerLab® Teaching Systems with LabTutor® and LabChart® soft ware have set the benchmarks in quality, ease-of-use, safety and fl exibility for over 20 years. Now, we’re proud to introduce another industry fi rst...the option to either buy or rent this powerful technology! Th e choice of purchase or rental options makes it even easier to get the world’s leading data acquisition system for Buy or Rent life science education. Our new Smart Rent Option off ers brand-new systems, low entry cost and free experiment soft ware upgrades. Talk to us to fi nd out more. Intuitive PowerLab Teaching Systems include experiments for human physiology, exercise physiology, pharmacology, Flexible Tool neurophysiology, psychophysiology, biology and more. Th e fl exibility of PowerLab systems adds to their cost- eff ectiveness – for purchasers and renters. Choose from over 100 experiments and 400 exercises More for introductory through to advanced levels. You can select the software for your courses and use authoring tools to modify/create experiments. Choose from over Experiments 20 Teaching Systems or let us create a customised solution. Contact us for an obligation-free demonstration. Tel: 01865 891 623 Email: [email protected] Web: www.adinstruments.com/buy_rent EQUIPMENT CERTIFIED FOR HUMAN CONNECTION UK • GERMANY • USA • BRAZIL • CHILE • INDIA • JAPAN • CHINA • MALAYSIA • NEW ZEALAND • AUSTRALIA CELEBRATING OVER 20 YEARS OF INNOVATIONS ADI_InstStudent_UK_PhysioNews.indd 1 15/5/09 2:32:20 PM PHYSIOLOGY NEWS Editorial 3 Meetings The Society’s dog. -

Pdf Once a Caian... 09 Issue 9 FINAL

EVENTS & REUNIONS FOR 2009 ISSUE 9 SPRING 2009 GONVILLE & CAIUS COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE Lent Full Term ends . Friday 13 March Telephone Campaign begins. Saturday 14 March MAs’ Dinner . Friday 20 March Annual Gathering (1987, 1988 & 1989) . Tuesday 24 March Caius Club Dinner . Saturday 28 March Easter Full Term begins . Tuesday 21 April Stephen Hawking Circle Dinner . Saturday 9 May Easter Full Term ends . Friday 12 June May Week Party for Benefactors . Saturday 13 June Caius Club Bumps Event. Saturday 13 June Caius Medical Association Meeting & Dinner . Saturday 20 June Graduation Tea . Thursday 25 June Annual Gathering (up to & including 1957). Tuesday 30 June Admissions Open Days . Thursday 2 & Friday 3 July 800th Anniversary London Concert. Wednesday 22 July 1969 Ruby Reunion Dinner . Sunday 13 September Annual Gathering (1996 & 1997) . Saturday 26 September Michaelmas Full term begins . Tuesday 6 October Please Note New Date: Commemoration of Benefactors Lecture. Sunday 22 November Commemoration of Benefactors Service . Sunday 22 November Commemoration Feast . Sunday 22 November First Christmas Carol Service (6pm) . Wednesday 2 December Second Christmas Carol Service (4.30pm). Thursday 3 December Michaelmas Full Term ends . Friday 4 December Caius Foundation Directors’ Meeting. Friday 4 December New York Reception . Friday 4 December Patrons of the Caius Foundation Dinner . Friday 4 December ...always aCaian Caius to China Editor: Mick Le Moignan Building Bridges Editorial Board: Dr Anne Lyon, Dr Jimmy Altham, Professor Wei-Yao Liang Design Consultant: Tom Challis Artwork and production: Cambridge Marketing Limited Gonville & Caius College Trinity Street Cambridge CB2 1TA United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1223 339676 Email: [email protected] [email protected] www.cai.cam.ac.uk/CaiRing/ From the Director of Development ...Always a Caian 1 This is a rather special issue of Once a Caian… As Cambridge University celebrates its 800th Anniversary, Caius is celebrating its close links with China. -

Ferdinand Hucho, Julia Diekämper, Heiner Fangerau, Boris Fehse

Ferdinand Hucho, Julia Diekämper, Heiner Fangerau, Boris Fehse, Jürgen Hampel, Kristian Köchy, Sabine Könninger, Lilian Marx-Stölting, Bernd Müller-Röber, Jens Reich, Hannah Schickl, Jochen Taupitz, Jörn Walter, Martin Zenke (Hrsg.) Martin Korte (Sprecher) Vierter Gentechnologiebericht Bilanzierung einer Hochtechnologie Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2018 ISBN: 978-3-8487-5183-9 (Forschungsberichte / Interdisziplinäre Arbeitsgruppen der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften ; 40) Persistent Identifier: urn:nbn:de:kobv:b4-opus4-30102 Die vorliegende Datei wird Ihnen von der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften unter einer Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivateWorks 4.0 International (cc by-nc-nd 4.0) Licence zur Verfügung gestellt. Forschungsberichte der interdisziplinären Arbeitsgruppen der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Vierter Gentechnologiebericht Bilanzierung einer Hochtechnologie Herausgegeben von Ferdinand Hucho | Julia Diekämper | Heiner Fangerau | Boris Fehse Jürgen Hampel | Kristian Köchy | Sabine Könninger | Lilian Marx-Stölting Bernd Müller-Röber | Jens Reich | Hannah Schickl | Jochen Taupitz Jörn Walter | Martin Zenke | Martin Korte (Sprecher) Nomos U1_4. GTB_BBAW_5183-9.indd 1 12.09.18 13:58 Forschungsberichte der interdisziplinären Arbeitsgruppen der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Vierter Gentechnologiebericht Bilanzierung einer Hochtechnologie Herausgegeben von Ferdinand Hucho | Julia Diekämper | Heiner Fangerau | Boris Fehse Jürgen Hampel | -

Calmodulin Dependent Protein Kinase

September 25, 2020 Vic Ramkumar, Ph.D. Intracellular Signaling & Signal Propagation CELL SIGNALING CYCLE AGONIST AGONIST (BRAIN DERIVED (Albuterol) NEUROTROPHIC FACTOR) RECEPTOR RECEPTOR SECOND MESSENGER PROTEIN KINASE PROTEIN KINASE ADAPTOR PROTEINS EFFECT EFFECT G Protein-Coupled Receptor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Section 1 What is Signal Transduction? Transmission of a signal from a hormone or drug to produce some cellular function. Signals are generally detected by receptor proteins present on the cell surface. Cell surface receptors discriminate the signals and channel these to specific cellular effectors to produce a function. Drugs mimic (agonists) or antagonize (antagonists) the effects of endogenous chemicals on receptors. EXTRACELLULAR SIGNALLING Relevant Concepts Types of signalling processes: Endocrine, paracrine, autocrine synaptic, plasma membrane attached protein Ligand Second messengers Receptors - G protein coupled receptors, ion channel receptor, tyrosine kinase-linked receptor, receptors with enzymatic activity Distance Communication EPINEPHRINE, GLUCAGON ACTH, INSULIN Local Communication CYTOKINES (IL-2), ADENOSINE, ADP Molecular Cell Biology, 4th Ed., Chapter 20 CYTOKINES, ADENOSINE T CELL Molecular Cell Biology, 4th Ed., Chapter 20 Model of Synaptic Transmission Receptors Nerve Terminal Axon Neurotransmitter Cell Body SYNAPSE • Agonists impart their information by increasing the generation of second messengers First Messenger Second Messengers Cyclic AMP Cyclic GMP Diacyl glycerol Inositol trisphosphate Molecular -

Heineken Lectures 2002

Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Heineken Lectures 2002 Heineken Lectures 2002 The Heineken Lectures were presented on 23 September 2002 Roger Y.Tsien, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Aernout Mik, AKI Enschede Dennis Selkoe, LUMC Leiden Heinz Schilling, Universiteit Leiden Lonnie Thompson, Universiteit Utrecht Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Heineken Lectures 2002 Amsterdam, 2003 The Heineken Prizes: five prizes for outstanding contributions to the arts and sciences Every two years the Dr H.P. Heineken Foundation and the Alfred Heineken Fondsen Foundation award four prizes – a cash gift of 150.000 USD and a cristal symbol – for outstanding contributions to the sciences and one prize for the performing arts to a Dutch artist (50.000 EUR). The selection of the winners for the Heineken Prizes has been entrusted to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Academy’s Arts and Sciences Divisions have appointed special committees to carry out this task. The jury of the Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for Art consist of three members of the Academy complemented by experts in the particular artistic field. The Academy also organized the Heineken Lectures 2002. The five laureates were asked to give a lecture about their work for a broad audi- ence at universities across the country.This is the unique publication of those five very diverse lectures given by the prizewinners, every one of them excellent in his or her own discipline. Contents page 6 Willem J.M. Levelt Preface 9 Roger Y.Tsien DR H.P. HEINEKEN PRIZE FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOPHYSICS Unlocking Cell Secrets with Light Beams and Molecular Spies 29 Aernout Mik DR A.H. -

Eureka Moments: the Key That Unlocked Calcium

Centenary News Michael Berridge in conversation with Robin Irvine Eureka moments: the key that unlocked calcium Sheila Alink-Brunsdon (Head of Group – Society Activities) Downloaded from http://portlandpress.com/biochemist/article-pdf/33/1/40/4085/bio033010040.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 As part of our Centenary celebrations, a number of the Society’s Honorary Members have been asked to talk about the important moments in their careers and the future of the discipline. These interviews will be made available throughout the year on the Society’s website as a series of podcasts. come over to the UK to do his PhD at Cambridge un- der Sir Vincent Wigglesworth. Michael remembered: “It was remarkable to come and work with essentially the father of insect physiology. It was tremendously inspiring to work with someone like that.” It was when working on the salivary glands of flies that he soon realized he would need new tech- niques to progress further. The problem that inter- ested Michael was how a hormone made a cell secrete saliva. “We all need to respond to our environment and that process begins at a cellular level. A signal reaches the surface of a cell, but how does that makes Sir Michael and Robin reminiscing The first to be released is that of Professor Sir Michael Berridge who spoke to Professor Robin Irvine about his ‘eureka moment’ in calcium signalling and his passion for trying to find the solution to interesting problems. Michael Berridge and Robin Irvine are old friends and, coming from com- pletely different fields of science, they changed our understanding of cell sig- nalling. -

Acknowledgment of Reviewers, 2009

Proceedings of the National Academy ofPNAS Sciences of the United States of America www.pnas.org Acknowledgment of Reviewers, 2009 The PNAS editors would like to thank all the individuals who dedicated their considerable time and expertise to the journal by serving as reviewers in 2009. Their generous contribution is deeply appreciated. A R. Alison Adcock Schahram Akbarian Paul Allen Lauren Ancel Meyers Duur Aanen Lia Addadi Brian Akerley Phillip Allen Robin Anders Lucien Aarden John Adelman Joshua Akey Fred Allendorf Jens Andersen Ruben Abagayan Zach Adelman Anna Akhmanova Robert Aller Olaf Andersen Alejandro Aballay Sarah Ades Eduard Akhunov Thorsten Allers Richard Andersen Cory Abate-Shen Stuart B. Adler Huda Akil Stefano Allesina Robert Andersen Abul Abbas Ralph Adolphs Shizuo Akira Richard Alley Adam Anderson Jonathan Abbatt Markus Aebi Gustav Akk Mark Alliegro Daniel Anderson Patrick Abbot Ueli Aebi Mikael Akke David Allison David Anderson Geoffrey Abbott Peter Aerts Armen Akopian Jeremy Allison Deborah Anderson L. Abbott Markus Affolter David Alais John Allman Gary Anderson Larry Abbott Pavel Afonine Eric Alani Laura Almasy James Anderson Akio Abe Jeffrey Agar Balbino Alarcon Osborne Almeida John Anderson Stephen Abedon Bharat Aggarwal McEwan Alastair Grac¸a Almeida-Porada Kathryn Anderson Steffen Abel John Aggleton Mikko Alava Genevieve Almouzni Mark Anderson Eugene Agichtein Christopher Albanese Emad Alnemri Richard Anderson Ted Abel Xabier Agirrezabala Birgit Alber Costica Aloman Robert P. Anderson Asa Abeliovich Ariel Agmon Tom Alber Jose´ Alonso Timothy Anderson Birgit Abler Noe¨l Agne`s Mark Albers Carlos Alonso-Alvarez Inger Andersson Robert Abraham Vladimir Agranovich Matthew Albert Suzanne Alonzo Tommy Andersson Wickliffe Abraham Anurag Agrawal Kurt Albertine Carlos Alos-Ferrer Masami Ando Charles Abrams Arun Agrawal Susan Alberts Seth Alper Tadashi Andoh Peter Abrams Rajendra Agrawal Adriana Albini Margaret Altemus Jose Andrade, Jr. -

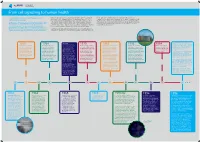

From Cell Signalling to Human Health

Babraham Institute From cell signalling to human health Co-ordination of cell activities through inositol Living cells are complex systems of molecules that work together to maintain life Inositol lipids are found in the membranes that enclose cells, in addition to and respond to ever-changing conditions. Cell signalling systems exist to detect forming structures changes in their abundance act as signals to alter gene activity, lipid signalling systems these changes and initiate appropriate responses within the cell. They do this by metabolism and other behaviours within a cell. Amongst other things, the balance Fundamental cell biology research at the Babraham Institute is laying controlling the activity of a small number of key ‘signal transduction’ proteins, of these lipids acts as a key control mechanism for cell growth, division and survival. the groundwork for new treatments for cancers, chronic inflammation which in turn regulate a cascade of further events. These include affecting the Disruption of inositol lipid signalling can lead to a range of illnesses including and other diseases all caused by defects in the mechanism that activity of other proteins, metabolic changes and altered gene expression. Together immunodeficiencies and cancers. transmits signals within cells. By working with companies on the these co-ordinate complex cell behaviour, such as growth and development. Babraham Research Campus, in the local Cambridge area and beyond, the Institute is ensuring a rapid development pathway from discovery Signalling research at the Babraham Institute has focused on systems that involve research to biotechnology, drug development and clinical application. regulating the abundance of a group of molecules called ‘inositol lipids’ inside cells.