26 Impact of Russian Hidden Economic Sanctions On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joint Barents Transport Plan Proposals for Development of Transport Corridors for Further Studies

Joint Barents Transport Plan Proposals for development of transport corridors for further studies September 2013 Front page photos: Kjetil Iversen, Rune N. Larsen and Sindre Skrede/NRK Table of Contents Table Summary 7 1 Introduction 12 1.1 Background 12 1.2 Objectives and members of the Expert Group 13 1.3 Mandate and tasks 14 1.4 Scope 14 1.5 Methodology 2 Transport objectives 15 2.1 National objectives 15 2.2 Expert Group’s objective 16 3 Key studies, work and projects of strategic importance 17 3.1 Multilateral agreements and forums for cooperation 17 3.2 Multilateral projects 18 3.4 National plans and studies 21 4 Barents Region – demography, climate and main industries 23 4.1 Area and population 23 4.2 Climate and environment 24 4.3 Overview of resources and key industries 25 4.4 Ores and minerals 25 4.5 Metal industry 27 4.6 Seafood industry 28 4.7 Forest industry 30 4.8 Petroleum industry 32 4.9 Tourism industry 35 4.10 Overall transport flows 37 4.11 Transport hubs 38 5 Main border-crossing corridors in the Barents Region 40 5.1 Corridor: “The Bothnian Corridor”: Oulu – Haparanda/Tornio - Umeå 44 5.2 Corridor: Luleå – Narvik 49 5.3 Corridor: Vorkuta – Syktyvkar – Kotlas – Arkhangelsk - Vartius – Oulu 54 5.4 Corridor: “The Northern Maritime Corridor”: Arkhangelsk – Murmansk – The European Cont. 57 5.5 Corridor: “The Motorway of the Baltic Sea”: Luleå/Kemi/Oulu – The European Continent 65 5.6 Corridor: Petrozavodsk – Murmansk – Kirkenes 68 5.7 Corridor: Kemi – Salla – Kandalaksha 72 5.8 Corridor: Kemi – Rovaniemi – Kirkenes 76 -

7 2018 Union of Industries of Railway Equipment (Uire)

#7 2018 UNION OF INDUSTRIES OF RAILWAY EQUIPMENT (UIRE) UIRE Members •C ABB LL • Emperor Alexander I St. Petersburg State • Academician N.A. Semikhatov Automatics Transport University Research & Production Corporation (NPOA) JSC • Energoservice LLC • All-Union research and development centre of • EPK-Brenсo Bearing Company LLC transport technologies (VNICTT) • EPK Holding Company JSC • Alstom Transport Rus LLC • EVRAZ Holding LLC • Amsted Rail Company inc • Expert Center for certification and licensing, LLC • ASI Engineering Center LLC • Eurosib SPb-TS, CJSC • Association of outsourcing agents NP • Faiveley Transport LLC • Association of railway braking equipment • Faktoriya LS manufacturers and consumers (ASTO) • Federal Freight JSC • AVP Technology LLC • FINEX Quality • Azovelectrostal PJSC • Fink Electric LLC • Balakovo Carbon Production LLC • Flaig+Hommel LLC • Baltic Conditioners LLC • Freight One JSC • Barnaul Car Repair Plant JSC • GEISMAR-Rus LLC • Barnaul plant of asbestos technical products JSC • HARP Oskol Bearing plant JSC • Bauman Moscow State Technical University • Harting CJSC • Belarusian Railways NU • Helios RUS LLC • Bridge and defectoscopy R&D Institute FSUE • Infrastructure and Education Programs • Cable Alliance Holding LLC Foundation of RUSNANO • Cable Technologies Scientific Investment • Information Technologies, LLC Center CJSC • Institute of Natural Monopolies Research • Car Repair Company LLC (IPEM) ANO • Car Repair Company One JSC • Interregional Group of Companies • Car Repair Company Two JSC INTEHROS CJSC • -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL TRANS/SC.2/2004/3 12 August 2004 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Rail Transport (Fifty-eighth session, 27-29 October 2004, agenda item 4) EURO-ASIAN TRANSPORT LINKS Activities related to the development of Euro-Asian transport links Note by the secretariat Following the request by the Working Party at its fifty-seventh session, the secretariat requested the information on ongoing developments along all four Euro-Asian land transport corridors (as agreed upon at the fourteenth session of the Working Party on Transport Trends and Economics (TRANS/WP.5/2001/14) from member Governments, international organizations and other relevant authorities. Based on these replies and other sources of information, the secretariat has prepared this note for consideration by the Working Party. __________ TRANS/SC.2/2004/3 page 2 INTRODUCTION The Second International Euro-Asian Conference on Transport, held in 2000 in St. Petersburg, identified the four Euro-Asian Land Transport Corridors presented to this Conference by UNECE and UNESCAP as constituting the main backbone of the Euro-Asian Land Transport System. All of these four Land Transport Corridors are overland with the exception of the Transsiberian that links to Japan over sea. The four corridors adopted in 2000 are: I Transsiberian Europe (PETCs 2, 3 and 9) – Russian Federation – Korean Peninsula-Japan, with two branches from the Russian Federation to: - Kazakhstan – China; - Mongolia – China. II TRACECA Eastern Europe (PETCs 4,7 8, and 9) – across Black Sea – Caucasus – across Caspian Sea – Central Asia. -

Reforming Europe's Railways

Innentitel 001_002_Innentitel_Impressum.indd 1 16.12.10 16:04 Reforming Europe's Railways – Learning from Experience Published by the Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies – CER Avenue des Arts 53 B -1000 Bruxelles www.cer.be second edition 2011 produced by Jeremy Drew and Johannes Ludewig Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek: The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e, detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://d-nb.de Publishing House: DVV Media Group GmbH | Eurailpress Postbox 10 16 09 · D-20010 Hamburg Nordkanalstraße 36 · D-20097 Hamburg Telephone: +49 (0) 40 – 237 14 02 Telefax: +49 (0) 40 – 237 14 236 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.dvvmedia.com, www.eurailpress.de, www.railwaygazette.com Publishing Director: Detlev K. Suchanek Editorial Office: Dr. Bettina Guiot Distribution and Marketing: Riccardo di Stefano Cover Design: Karl-Heinz Westerholt Print: TZ-Verlag & Print GmbH, Roßdorf Copyright: © 2011 by DVV Media Group GmbH | Eurailpress, Hamburg This publication is protected by copyright. It may not be exploited, in whole or in part, without the approval of the publisher. This applies in particular to any form of reproduction, translation, microfilming and incorporation and processing in electric systems. ISBN 978-3-7771-0415-7 A DVV Media Group publication DVV Media Group 001_002_Innentitel_Impressum.indd 2 16.12.10 16:04 Contents Foreword.................................................................................................... -

The Railways of Latvia Toms Altbergs Karīna Augustāne Ieva Pētersone the RAILWAYS of LATVIA

The Railways of Latvia Toms Altbergs Karīna Augustāne Ieva Pētersone THE RAILWAYS OF LATVIA Translated by Daina Grosa UDK 656.2(474.3)(091) Ra 314 Foreword Th is book was published with the support of State Joint Stock Company “Latvijas dzelzceļš” Th e national railway company of Latvia — State Joint Stock Company Latvijas dzelzceļš which recently became a concern, is one of the nation’s largest companies and one of the strongest economically. Th e history of the railways in the territory of Latvia dates back 150 years. Latvian State Railways was founded on 5 August 1919. Th e Railway Central Board took on the task of transforming the railways that had been Design Jānis Jaunarājs devastated by World War I and the chaos that followed and over a 20 year Managing Editor Evija Veide period established one of the most extensive and modern railway networks Copy Editor Marianna Auliciema in Europe. Th e network was founded on the legacy of tsarist Russia, with over 800 km of railways constructed, and so a structurally well-balanced railway system was established. Th is provided domestic and transit trans- The photographs and documents used in this book have been sourced from the collections at the Power Industry Museum, National History Museum of port services to the east and the west. Working on the railways symbolised Latvia, Latvian Railway History Museum, October Railway Central Museum stability and being a railwayman became one of the most prestigious and and the Lithuanian Railway Museum as well as the private archives of Vladimirs Eihenbaums, Dainis Punculs, Arnis Dambis, Dzintra Rupeika, Manfred best-paid professions. -

Concerning Approval of Related Party Transactions

Statement of Material Fact “Individual decisions made by the Issuer’s Board of Directors” 1. General Information 1.1. Full corporate name of the issuer Joint-Stock Company Centre for the Transport of Goods in Containers (TransContainer) 1.2. Short corporate name of the issuer JSC TransContainer 1.3. Issuer’s registered address Oruzheyniy Pereulok 19 Moscow, Russian Federation 12504 1.4. Issuer’s Principal State Registration Number 1067746341024 (OGRN) 1.5. Issuer’s Taxpayer Identification Number 7708591995 (INN) 1.6. Issuer’s unique code assigned by the 55194-E registration agency 1.7. Webpage used by the issuer for disclosure of http://www.trcont.ru information http://www.e- disclosure.ru/portal/company.aspx?id=11194 2. Contents of the Statement Concerning approval of transactions that are classified as related party transactions in accordance with the laws of the Russian Federation 2.1. The quorum of the meeting of the Issuer’s Board of Directors: 11 of 11 members of the Board of Directors of JSC TransContainer participated in the meeting of the Board of Directors. In accordance with Article 68 and 83 of the Federal Law “On Joint-Stock Companies”, the quorum is present and the meeting of the Board of Directors of JSC TransContainer can proceed to business. 2.2. The results of voting on the issues relating to making decisions: 2.2.1. About the approval of the lease agreement on the large-capacity containers between the JSC "TransContainer" and "TransContainer Europe GmbH". For: 7. Against: none. Abstained: none. When summarizing the results of voting on the issues, the votes of a Board member P.V. -

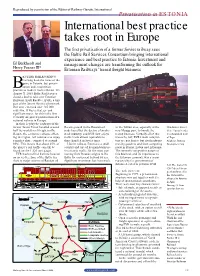

International Best Practice Takes Root in Europe

Privatisation in ESTONIA International best practice takes root in Europe The first privatisation of a former Soviet railway sees the Baltic Rail Services Consortium bringing international experience and best practice to Estonia. Investment and Ed Burkhardt and management changes are transforming the outlook for Henry Posner III* Estonian Railways’ transit freight business IG-TIME RAILROADING has long been the name of the game in Estonia, but privati- sation and competition Bpromise to make it more efficient. On August 31 2001 Baltic Rail Services closed a deal to take over Estonian Railways (Eesti Raudtee, EVR), a tiny part of the former Soviet rail network that once extended over 145 000 route-km. It was a strategic and significant move, for this is the first vertically-integrated privatisation of a national railway in Europe. In their heyday the railways of the former Soviet Union handled around Recent growth in the Russian oil in the Tallinn area, especially at the Two former Soviet half the world’s rail freight traffic. trade has offset the decline of smoke- new Muuga port, to handle the diesel locos head a Despite the economic collapse affect- stack industry, and EVR now enjoys transit business. Virtually all of this westbound oil train ing the region, rail continues to enjoy traffic levels almost equivalent to moves by rail; EVR’s main competi- at Tapa a market share estimated at around those handled in Soviet times. tors are not lorries, but rival railways All photos: Railroad 80%. This means that about 25% of Like its railway, Estonia is a small moving goods to and from competing Development Corp the planet’s rail traffic can still be country and one of its main business- ports in Russia, Latvia and Lithuania. -

Steam Locomotive

Company profile Messages from Management Strategic report 6 180 By the end of the 19th century, Russia had a railway construction and management system in place. In 1893, a general freight transportation fare was introduced, followed years by a common passenger fare in 1894. These developments helped improve passenger and freight turnover. Also, railway network expansion would be impossible without a strong of Russian railways' domestic industry for locomotive and railcar construction history and rail rolling mills. 1898 Steam locomotive 3,277 m poods, equal to 52 mt of freight carried in one year Source: Statistical digest “Transportation of Freight by Railway – 1901 Results” Russian Railways Performance overview Sustainable development Corporate governance 7 Railways in Russia 2017 Modern freight train 1,384 mt of freight carried in 2017 Concise Annual Report 2017 Company profile Messages from Management Strategic report 8 180 30 October 1837 is the official opening date of the Tsarskoye Selo Railway in St Petersburg. It was a short line running for a little longer than 26 km with only one 8-carriage train years hauled by a steam locomotive. However short, this line became an important landmark in the history of transport as an indication of the overall feasibility of construction of Russian railways' and year-round operation of railways in the Russian climate. history 1851 Launch of service on the Nikolaev (currently October) Railway connecting St Petersburg and Moscow. Passenger train 4 with steam trains a day locomotive This was the first government-owned main line railway in Russia and the first step in building a nationwide railway network. -

Migrants and Muscovites: the Boundaries of Belonging in Moscow, 1971-2002

MIGRANTS AND MUSCOVITES: THE BOUNDARIES OF BELONGING IN MOSCOW, 1971-2002 By Emily Joan Elliott A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT MIGRANTS AND MUSCOVITES: THE BOUNDARIES OF BELONGING IN MOSCOW, 1971-2002 By Emily Joan Elliott This dissertation examines Soviet and post-Soviet Russian attempts to control temporary labor migration to Moscow from 1971 to 2002. Under both the Soviet command economy and the Russian capitalist one, Moscow faced a chronic shortage of workers to fill unskilled, physically demanding positions in the industrial, construction, and transportation sectors. By analyzing how the Office for the Use of Labor Resources in Moscow regulated migration to the capital, I elucidate how the boundaries of belongings in Moscow shifted in conjunction with larger economic and demographic concerns. Soviet policy required that all residents of Moscow (as well as other cities) apply for a residency permit and provide proof of a job before relocating. Russian authorities adapted this policy, requiring all residents – including visitors – to announce their presence with the policy. Contrary to what might be expected, the registration became a much more repressive tool of exclusion in the post-Soviet period. In the 1970s, Soviet social support, particularly in workers’ dormitories, was crucial for the social integration of these temporary labor migrants, known as limitchiki. These programs correlated with reduced labor turnover and increased productivity. Moreover, this dissertation argues that the economic uncertainty that began under perestroika unleashed anti-migrant sentiment. Muscovites held the limitchiki responsible for the capital’s untamed population growth and blamed them for taxing the city’s infrastructure – the very infrastructure that the limitchiki had been hired to build and maintain. -

Russian Railways Annual Report 12821H.Pdf

Concise Open Joint Stock Company Annual Report 2017 Russian Railways Agenda COMPANY PROFILE 2 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 62 Operating highlights 4 Stakeholder engagement 63 180 years of Russian railway history 6 HR management 64 Occupational safety 66 MESSAGES FROM RUSSIAN RAILWAYS Environmental protection 66 MANAGEMENT 12 Message from the Chairman CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 68 of the Russian Railways Board of Directors 12 Corporate governance system 68 Message from the CEO and Chairman of the Management Board 14 Russian Railways' General Meeting of Shareholders 70 Russian Railways' Board of Directors 71 STRATEGIC REPORT 16 Russian Railways' Management Board 73 Control 75 New horizons 16 Risk management system 77 Russian Railways' Strategy 20 Key performance indicators 22 Development prospects in 2018 23 Russian Railways Group’s business model 24 PERFORMANCE OVERVIEW 26 Market overview 26 Analysis of operating results 28 Traffic safety 44 Investment activities 45 Innovation driven development 50 Analysis of financial results 51 Securities 59 Messages from Russian Railways Company profile Strategic report Management 2 COM PANY PRO FILE Open Joint Stock Company Russian Railways is Russia's largest railway company engaged in owning and building public railway infrastructure. The Company ranks among the world’s leading railway carriers by freight and passenger transportation volumes and length of railway lines. Russian Railways today Owner of the world's Unique and highly third longest railway network diversified group The operational length of Russian Russian Railways owns railway Railways’ lines stands at 85.5 thousand infrastructure and rolling stock km, more than twice the length to transport freight and passengers, of the equator. Russian Railways provide transportation, logistics, terminal, is the second largest company warehousing, and freight forwarding globally by length of electrified lines services. -

The Role of Socialist Competition in Establishing Labour Discipline in the Soviet Working Class, 1928-1934 Part 2

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. 2nd of 2 files Part Two: Chapters 5 to 7 Appendices and Bibliography THE ROLE OF SOCIALIST COMPETITION IN ESTABLISHING LABOUR DISCIPLINE IN THE SOVIET WORKING CLASS, 1928-1934 By John Russell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Russian and East European Studies Commerce & Social Science Division University of Birmingham 1987 PART TWO -151- SOCIALIST COMPETITION Introduction Among the most striking features of the Soviet industrialisation drive during the period under review that distinguish it from corresponding developments in other countries was the role accorded to socialist competition. The importance attached to this phenomenon by the Party leadership and the speed with which it spread through Soviet society are attested to by the fact that at the beginning of 1929 the term 'socialist competition' (sotsialisticheskoe sorevnovanie) had yet to be coined, whereas by the end of that year it had already become an integral and, as it transpired, permanent feature of Soviet industrial relations. This Chapter examines the origins, aims development and characteristics of socialist competition with special reference to its role in the establishment of labour discipline. -

Public-Private Partnership Investments in Dry Ports – Russian Logistics Markets and Risks

Yulia Panova PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP INVESTMENTS IN DRY PORTS – RUSSIAN LOGISTICS MARKETS AND RISKS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Science (Technology) to be presented with due permission for public examination and criticism in Honka Hall, Kouvola House, Kouvola, Finland, on the 8th of April, 2016, at noon. Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis 689 Su pervisor Professor Olli-Pekka Hilmola Kouvola Unit Lappeenranta University of Technology Finland Reviewers Professor Yacan Wang School of Economics and Management Beijing Jiaotong University China Professor Per Hilletofth School of Engineering Jönköping University Sweden Opponents Associate Professor Andres Tolli Estonian Maritime Academy Tallinn University of Technology Estonia Professor Per Hilletofth School of Engineering Jönköping University Sweden ISBN 978-952-265-924-8 ISBN (PDF) 978-952-265-925-5 ISSN-L 1456-4491 ISSN 1456-4491 Lappeenranta University of Technology Yliopistopaino 2016 Abstract Yulia Panova Public-private partnership investments in dry ports – Russian logistics markets and risks Lappeenranta 2016 218 p. Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis 689 Diss. Lappeenranta University of Technology ISBN 978-952-265-924-8 ISBN (PDF) 978-952-265-925-5 ISSN-L 1456-4491 ISSN 1456-4491 The investments have always been considered as an essential backbone and so-called ‘locomotive’ for the competitive economies. However, in various countries, the state has been put under tight budget constraints for the investments in capital intensive projects. In response to this situation, the cooperation between public and private sector has grown based on public-private mechanism. The promotion of favorable arrangement for collaboration between public and private sectors for the provision of policies, services, and infrastructure in Russia can help to address the problems of dry ports development that neither municipalities nor the private sector can solve alone.