Iowa's Non-Native Graminoids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematics and Evolution of Eleusine Coracana (Gramineae)1

Amer. J. Bot. 71(4): 550-557. 1984. SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION OF ELEUSINE CORACANA (GRAMINEAE)1 J. M. J. de W et,2 K. E. Prasada Rao,3 D. E. Brink,2 and M. H. Mengesha3 departm ent of Agronomy, University of Illinois, 1102 So. Goodwin, Urbana, Illinois 61801, and international Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics, Patancheru, India ABSTRACT Finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn. subsp. coracana) is cultivated in eastern and southern Africa and in southern Asia. The closest wild relative of finger millet is E. coracana subsp. africana (Kennedy-O’Byme) H ilu & de Wet. W ild finger m illet (subsp. africana) is native to Africa but was introduced as a weed to the warmer parts of Asia and America. Derivatives of hybrids between subsp. coracana and subsp. africana are companion weeds of the crop in Africa. Cultivated finger millets are divided into five races on the basis of inflorescence mor phology. Race coracana is widely distributed across the range of finger millet cultivation. It is present in the archaeological record o f early African agriculture that m ay date back 5,000 years. Racial evolution took place in Africa. Races vulgaris, elongata., plana, and compacta evolved from race coracana, and were introduced into India some 3,000 years ago. Little independent racial evolution took place in India. E l e u s i n e Gaertn. is predominantly an African tancheru in India, and studied morphologi genus. Six of its nine species are confined to cally. These include 698 accessions from the tropical and subtropical Africa (Phillips, 1972). -

Processing, Nutritional Composition and Health Benefits of Finger Millet

a OSSN 0101-2061 (Print) Food Science and Technology OSSN 1678-457X (Dnline) DDO: https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.25017 Processing, nutritional composition and health benefits of finger millet in sub-saharan Africa Shonisani Eugenia RAMASHOA1*, Tonna Ashim ANYASO1, Eastonce Tend GWATA2, Stephen MEDDDWS-TAYLDR3, Afam Osrael Dbiefuna JODEANO1 Abstract Finger millet (Eleusine coracana) also known as tamba, is a staple cereal grain in some parts of the world with low income population. The grain is characterized by variations in colour (brown, white and light brown cultivars); high concentration of carbohydrates, dietary fibre, phytochemicals and essential amino acids; presence of essential minerals; as well as a gluten-free status. Finger millet (FM) in terms of nutritional composition, ranks higher than other cereal grains, though the grain is extremely neglected and widely underutilized. Nutritional configuration of FM contributes to reduced risk of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure and gastro-intestinal tract disorder when absorbed in the body. Utilization of the grain therefore involves traditional and other processing methods such as soaking, malting, cooking, fermentation, popping and radiation. These processes are utilised to improve the dietetic and sensory properties of FM and equally assist in the reduction of anti-nutritional and inhibitory activities of phenols, phytic acids and tannins. However, with little research and innovation on FM as compared to conventional cereals, there is the need for further studies on processing methods, nutritional composition, health benefits and valorization with a view to commercialization of FM grains. Keywords: finger millet; nutritional composition; gluten-free; antioxidant properties; traditional processing; value-added products. Practical Application: Effects of processing on nutritional composition, health benefits and valorization of finger millet grains. -

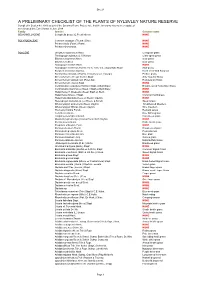

A Preliminary Checklist of the Plants of Nylsvley

Sheet2 A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF THE PLANTS OF NYLSVLEY NATURE RESERVE Compiled in September 1983 as part of the Savanna Biome Project note that the taxonomy has not Been updated merely typed into Excel format in June 2014 Family Species Common name SELAGINELLACEAE Selaginella dregei (C.Presl) Hieron NONE POLYPODIACEAE Ceterach cordatum (Thumb.) Desv. NONE Pellaea viridis (Forsk.) Prantl. NONE Pellaea colomelanos. NONE POACEAE Urelytrum squarrosum Hack. Centipede grass Trachypogon spicatus (L.f.) Kuntze Giant spear grass Elionurus argenteus Nees. Sour grass Elionurus muticus Sour grass Andropogon schinzii Hack. NONE Andropogon schirensis Hochst. Ex A. Rich. Var. angustifolia Stapf. StaB grass Sorghum versicolor Anderss. Black-seed Wild Sorghum Bothriochloa insculpta (Hochst.) A.Camus var. insculpta. Pinhole grass Schizachyrium jeffreysii (Hack.) Stapf. Silky Autumn Grass Schizachyrium sanguineum (Retz) Alst. Red Autumn Grass Schizachyrium ursulus Stapf. NONE Cymbopogon excavatus (Hochst.) Stapf ex Burtt Davy. Broad-Leaved Turpentine Grass Cymbopogon marginatus (Steud.) Stapf ex Burtt Davy. NONE Hyparrhenia cf. Dregeana (Nees) Stapf ex Stent. NONE Hyparrhenia hirta (L.) Stapf. Common thatchgrass Hyperthelia dissoluta (nees ex Steud.) Clayton. NONE Heteropogon contortus (L.) ex Roem. & Schult. Spear Grass Diheteropogon amplectens (Nees) Clayton. Broadleaved Bluestem Diheteropogon filifolius (Nees) Clayton. Wire Bluestem Themeda triandra Forssk. Red Oat Grass Cenchrus ciliaris L. Blue Bufallograss Tragus Berteronianus Schult. Carrotseed grass Mosdenia leptostachys (Fical.& Hiern) W.D.Clayton NONE Perotis patens Gand. Bottle-brush grass Paspalum orbiculare Forst. NONE Panicum deustum ThunB. Broadleaved panic Panicum dregeanum Nees. Plum panicum Panicum cf.laevifolium Hack. Blue panic Panicum maximum Jacq. Guinea grass Panicum natalense Hochst. Natal Buffalo Grass Alloteropsis semialata (R.Br.) Hitchc. -

Common Carpetgrass (Axonopus Fissifolius)

Weed Technology Common carpetgrass (Axonopus fissifolius) www.cambridge.org/wet control with POST herbicides Gerald Henry1, Christopher Johnston2, Jared Hoyle3, Chase Straw4 and Kevin Tucker5 Research Article 1Professor, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA; 2Graduate student, Cite this article: Henry G, Johnston C, Hoyle J, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA; 3Assistant Professor, Department Straw C, Tucker K (2019) Common carpetgrass of Horticulture and Natural Resources, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA; 4Postdoctoral Research (Axonopus fissifolius) control with POST 5 herbicides. Weed Technol. doi: 10.1017/ Associate, Department of Horticultural Science, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA and Research wet.2019.17 Associate, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA Received: 18 August 2018 Abstract Revised: 22 February 2019 Accepted: 25 February 2019 Reductions in MSMA use for weed control in turfgrass systems may have led to increased common carpetgrass infestations. The objective of our research was to identify alternative Associate Editor: POST herbicides for control of common carpetgrass using field and controlled-environment Scott McElroy, Auburn experiments. Field applications of MSMA (2.2 kg ai ha−1) and thiencarbazone þ iodosulfuron þ −1 Keywords: dicamba (TID) (0.171 kg ai ha ) resulted in the greatest common carpetgrass control 8 wk Golf course; weed management after initial treatment (WAIT): 94% and 91%, respectively. Thiencarbazone þ foramsulfuron þ halosulfuron (TFH) (0.127 kg ai ha−1) applied in the field resulted in 77% control 8 WAIT, Nomenclature ≤ Dicamba; foramsulfuron; halosulfuron; whereas all other treatments were 19% effective at 8 WAIT. -

(Gramineae) in Malesia

BLUMEA 21 (1973) I—Bo1 —80 A revision of DigitariaHaller (Gramineae) in Malesia. Notes on Malesian grasses VI J.F. Veldkamp Rijksherbarium, Leiden '...a material stronger than armor: Crabgrass' Parker & The is (B. J. Hart, King a Fink, 1964) Contents Summary 1 General introduction 2 Part 1. General observations Nomenclature A. 4 B. Taxonomic position 6 C. Morphology 7 D. Infra-generic taxonomy 12 E. Infra-specific taxonomy and genetics 17 F. Cultivated species 19 G. References 19 Part II. Descriptive part of data A. Presentation 22 B. Guide to the key and descriptions 22 c. Key 23 D. Descriptions 27 E. dubiae vel excludendae Species 71 Index 74 Summary Inthis revision is of the Malesian paper a given species ofthe Crabgrasses, or Digitaria Haller ( Gramineae). The research was done at the Rijksherbarium, Leyden, while many other Herbaria were shortly visited; some field work was done in Indonesia, Australia, and Papua-New Guinea. the in The foundation for study this large and cosmopolitan genus must be Henrard’s monumental work of the which therefore cited ‘Monograph genus Digitaria’ (1950), is extensively and discussed. in in the the Henrard based his division sections, 32 subgenus Digitaria, with anemphasis on amount of and the various of but such subdivision spikelets per grouplet types hairs, a appears difficult to maintain. As in only part of the species of Digitaria occurs Malesia, not representing all sections, a new infra-generic can be As far as the sections Malesia system not given. present in are concerned, it appeared that the Biformes, Horizontales, and Parviglumaehad to be united with the section Digitaria, the Remotae and Subeffusae had to into be merged one, the Remotae, while the Atrofuscae had to be included, at least partly, in the Clavipilae, here renamed is Filiformes. -

KEY GRASS SPECIES in VEGETATION UNIT Gm 11: Rand Highveld Grassland in MPUMALANGA PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA

IDENTIFICATION OF KEY GRASS SPECIES IN VEGETATION UNIT Gm 11: Rand Highveld Grassland IN MPUMALANGA PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA Winston S.W. Trollope & Lynne A. Trollope 22 River Road, Kenton On Sea, 6191, South Africa Cell; 082 200 33373 Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Veld condition refers to the condition of the vegetation in relation to some functional characteristic/s (Trollope, et.al., 1990) and in the case of both livestock production and wildlife management based on grassland vegetation, comprises the potential of the grass sward to produce forage for grazers and its resistance to soil erosion as influenced by the basal and aerial cover of the grass sward. The following procedure was used for developing a key grass species technique for assessing veld condition in the vegetation type Gm 11: Rand Highveld Grassland (Mucina & Rutherford, 2006) in Mpumalanga Province – see Figure 1. Rand Highveld Grassland: Gm11 Figure 1: The Rand Highveld Grassland Gm11 vegetation type located in the highveld area east of Pretoria in Mpumalanga Province (Mucina & Rutherford, 2006). The identification of the key grass species is based on the procedure developed by Trollope (1990) viz.. Step 1: Identify and list all the grass species occurring in the study area noting their identification characteristics for use in the field. Step 2: Based on careful observations in the field and consultations with local land users, subjectively classify all the known grass species in the area into Decreaser and Increaser species according to their reaction to a grazing gradient i.e. from high to low grazing intensities, as follows: DECREASER SPECIES: Grass & herbaceous species that decrease when veld is under or over grazed; 2 INCREASER I SPECIES: Grass & herbaceous species that increase when veld is under grazed or selectively grazed; INCREASER II SPECIES: Grass & herbaceous species that increase when veld is over grazed. -

Eleusine Indica (L.) Gaertn., New Species of the Adventive Flora of Slovakia

Thaiszia - J. Bot., Košice, 29 (1): 077-084, 2019 THAISZIA https://doi.org/10.33542/TJB2019-1-06 JOURNAL OF BOTANY Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn., new species of the adventive flora of Slovakia Zuzana Dítě1, Daniel Dítě1 & Viera Feráková2 1 Institute of Botany, Plant Science and Biodiversity Center, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, SK-845 23, Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] 2 Karloveská 23/43, 84104 Bratislava Dítě Z., Dítě D., Feráková V. (2019): Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn., new species of the adventive flora of Slovakia. – Thaiszia – J. Bot. 29 (1): 077-084. Abstract: First two records of Eleusine indica in Slovakia are presented. This exotic grass species originating from the tropical Old World was found in the Podunajská nížina Lowland (Eupannonicum): in 2017 in Štúrovo and the next year in Bratislava, municipal part Karlova Ves. Both populations counted only three individuals grown in the pavement cracks. The habitat conditions of each locality in detail are characterized. Whereas Slovakia is among the last countries where E. indica was just discovered within Europe, we discuss the environmental conditions and the origin of the species in the backlight of earlier studies related to its occurrence in the surrounding countries. Key words: urban ecosystems, roadsides, new record, Eleusine indica, casual alien, plant invasion Introduction Eleusine indica is a late summer annual grass. Its long, spreading spikes resemble goose feet. Confusion with other grasses of digitate inflorescence (e.g. with Digitaria or Cynodon) is possible, but E. indica ‘s flattened culms, bright green leaves, size of many-flowered spikelets, and lack of awns serve to distinguish (Clayton et al. -

Appendix B Botanical and Faunal Surveys

APPENDIX B BOTANICAL AND FAUNAL SURVEYS BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SURVEY for the WAIKAPU COUNTRY TOWN PROJECT WAIKAPU, WAILUKU DISTRICT, MAUI by Robert W. Hobdy Environmental Consultant Kokomo, Maui February 2013 Prepared for: Waikapu Properties LLC 1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SURVEY WAIKAPU COUNTRY TOWN PROJECT Waikapū, Maui, Hawaii INTRODUCTION The Waikapū Country Town Project lies on approximately 520 acres of land on the southeast slopes of the West Maui mountains just south of Waikapū Stream and the village of Waikapū (see Figure 1). The project area straddles the Honoapi′ilani Highway and includes the Maui Tropical Plantation facilities and surrounding agriculture and pasture lands, TMKs (2) 3-6-02:003 por., (2) 3-6-04:003 and 006 por. and (2) 3-6-05:007. SITE DESCRIPTION The project area includes about 70 acres that comprise the facilities of the Maui Tropical Plantation. This is surrounded by 50 acres of vegetable farm. On the slopes above this are 150 acres of cattle pasture, and below the highway are 240 acres in sugar cane production. Elevations range from 250 feet at the lower end up to 800 feet at the top of the pastures. Soils are all deep, well-drained alluvial soils which are classified in the Wailuku Silty Clay, Iao Clay and Pulehu Cobbly Clay Loam soil series (Foote et al, 1972). The vegetation consists of a great variety of ornamental plant species on the grounds of the Maui Tropical Plantation, a diversity of vegetable crop plants, pasture grasses and dense fields of sugar cane. Annual rainfall ranges from 25 inches in the lower end up to 30 inches at the top (Armstrong, 1983). -

Digitaria Exilis (Kippist) Stapf) from West Africa

agronomy Article Agromorphological Characterization Revealed Three Phenotypic Groups in a Region-Wide Germplasm of Fonio (Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf) from West Africa Abdou R. Ibrahim Bio Yerima 1,2 , Enoch G. Achigan-Dako 1,* , Mamadou Aissata 2, Emmanuel Sekloka 3 , Claire Billot 4,5, Charlotte O. A. Adje 1, Adeline Barnaud 6 and Yacoubou Bakasso 7 1 Laboratory of Genetics, Biotechnology and Seed Sciences (GBioS), Faculty of Agronomic Sciences (FSA), University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Cotonou 01 BP 526, Benin; [email protected] (A.R.I.B.Y.); [email protected] (C.O.A.A.) 2 Department of Rainfed Crop Production (DCP), National Institute of Agronomic Research of Niger (INRAN), Niamey BP 429, Niger; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Phytotechny, Plant Breeding and Plant Protection (LaPAPP), Department of Sciences and Techniques of Vegetal Production (STPV), Faculty of Agronomy, University of Parakou, Parakou BP 123, Benin; [email protected] 4 Unité Mixte de Recherche Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes (AGAP), Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), F-34398 Montpellier, France; [email protected] 5 Amélioration Génétique et Adaptation des Plantes (AGAP), University of Montpellier, CIRAD, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), l’Institut Agro/Montpellier SupAgro, 2 Place Pierre Viala, 34060 Montpellier, France 6 Diversité, Adaptation et Développement des Plantes (DIADE), Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), University of Montpellier, 34060 Montpellier, France; [email protected] 7 Faculty of Science and Techniques, University of Abdou Moumouni of Niamey, Niamey BP 10662, Niger; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +229-95-393283 or +227-96-401486 Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: Fonio is an ancient orphan cereal, cultivated by resource-poor farmers in arid and semi-arid regions of West Africa, who conserved and used the cereal for nutrition and income generation. -

Efficacy of Two Dithiopyr Formulations

HORTSCIENCE 45(6):961–965. 2010. and warm-season turfgrasses (Chism and Bingham, 1991; Dernoeden et al., 2003; Enache and Ilnicki, 1991; Hart et al., 2004; Efficacy of Two Dithiopyr Johnson, 1994a, 1994b, 1995, 1996; Reicher et al., 1999); however, turfgrass injury after Formulations for Control of Smooth treatment with quinclorac has been reported to vary considerably. For example, Johnson Crabgrass [Digitaria ischaemum (1997) reported as high as 65% centipedegrass [Eremochloa ophiuroides (Munro) Hack] in- jury after treatment with quinclorac at 0.84 (Schreb) Schreb. ex Muhl.] at kgÁha–1. Reicher et al. (2002) suggested that caution be exercised when applying quinclorac Various Stages of Growth in regions where elevated air temperatures 1 occur early in the growing season. Warm air James T. Brosnan and Gregory K. Breeden temperatures could explain the increased levels Department of Plant Sciences, University of Tennessee, 252 Ellington Plant of turf injury that have been observed with Sciences, 2431 Joe Johnson Drive, Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 quinclorac applications to certain bermuda- grass cultivars in the transition zone (Johnson, Patrick E. McCullough 1995, 1996; McElroy et al., 2005). Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, University of Georgia, Griffin, GA Although MSMA has been commonly 30223-1797 used for POST smooth crabgrass control in bermudagrass turf, a U.S. Environmental Pro- Additional index words. turfgrass management, quinclorac, pre-emergence, postemergence, tection Agency (EPA) ruling determined that summer annual, grassy weed applications of MSMA for turfgrass weed control would not be legal after 2013 (U.S. Abstract. Although dithiopyr has been used for smooth crabgrass [Digitaria ischaemum EPA, 2009). -

Large Crabgrass Row Crop

Large Crabgrass [Digitaria sanquinalis (L.) Scop.] Row Crop Victor Maddox, Ph.D., Extension Associate, Mississippi State University John D. Bryd, Extension Professor, Mississippi State University Randy Westbrooks, Ph.D., U.S. Geological Survey, Whiteville, N.C. Fig. 1. Large crabgrass in bloom on a road- Fig. 2. Large crabgrass sheath with long Fig. 3. Large crabgrass infloresence. side with other vegetation. hairs. Introduction Problems Created Large crabgrass [Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.], sometimes called hairy crabgrass, is an annual, spreading grass prob- lematic in areas where grasses are desired, such as pastures, turf, and roadsides and disturbed areas like rowcrops and gardens throughout the MidSouth. Large crabgrass has also been used as a forage. Regulations Large crabgrass is not regulated as a noxious weed in the MidSouth. Description Vegetative Growth Large crabgrass is an annual warm-season grass reaching around 3’ in height with good conditions. Plants are caespi- tose, but mat-forming and rooting at the lower nodes. Lower nodes are hairy, but upper nodes may be smooth. Flowering shoots ascending with leaves usually flat, blades around 0.25’’ to 0.5’’ wide and 2’’ to 6’’ long. Blades are pubescent to rough, often with long hairs on leaf margins near the sheath. Sheaths are hairy (papillose-pilose), especially the lower sheaths. Ligules are membranous with a fringe of hairs, 2 to 3 mm long. Flowering Flowering occurs from July to October. The inflorescences are racemes, 3 to 9, and digitate. Racemes are 2’’ to 6’’ long, in 1 or 2 whorls, with a winged rachis (0.8 to 1 mm wide). -

Large and Small Crabgrass Life History Related to Weed Control

This bulletin is one of a series that pertains to life history studies of weeds that are important in the Northeastern states. This series of bulletins is being published by the Northeast Regional Weed Control Technical Committee (NE-42). Bulletins previously published pertain to the following weeds: nutgrass (Rhode Island Agr. Expt. Sta. Bul. 364. 1962), quackgrass (Rhode Island Agr. Expt. Sta. Bul. 365. 1962), horse nettle (Rhode Island Agr. Expt. Sta. Bul. 368. 1962), yellow foxtail and giant foxtail (Rhode Island Agr. Expt. Sta. Bul. 369. 1963) and barnyardgrass (Delaware Agr. Expt. Sta. Bul. 368. 1968) AUTHORS R. A. Peters, University of Connecticut Stuart Dunn, University of New Hampshire COOPERATING AGENCIES AND PERSONNEL Administrative Advisor: W. C. Kennard, Connecticut, Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Committee Members: Connecticut (Storrs) R. A. Peters Delaware E. M. Rahn Maryland J. V. Parochetti Massachusetts J. Vengris New Hampshire Stuart Dunn (retired) New Jersey R. D. Ilnicki and J. C. Cialone New York (Ithaca) R. D. Sweet and W. B. Duke Pennsylvania N. C. Hartwig Rhode lsland R. S. Bell West Virginia Collins Veatch Eastern Shore Branch, Virginia Truck Experiment Station H. P. Wilson Cooperative Federal Members: Cooperative State Research Service A. J. Loustalot Washington, D. C. Crops Research Division, ARS: Beltsville, Maryland L. L. Danielson New Brunswick, New Jersey W. V. Welker Contributors: John A. Meade, Maryland Wayne L. Currey and Robert O'Leary, (Storrs), Connecticut Herbert L. Cilley, New Hampshire 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………… 4 DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS ………………………………… 4 MORPHOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT ………………………………….. 5 Vegetative development ………………………………………………. 6 Effect of temperature on crabgrass development ……………………….