The Ehingers and Welsers in Venezuela, 1520-1560

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference. -

German Views of Amazonia Through the Centuries

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2012 German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries Richard Hacken [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hacken, Richard, "German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries" (2012). Faculty Publications. 2155. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/2155 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries Amazonia has been called “…the most exuberant celebration of life ever to have existed on earth.”i It has been a botanical, zoological and hydrographic party for the ages. Over the past five centuries, German conquistadors, missionaries, explorers, empresses, naturalists, travelers, immigrants and cultural interpreters have been conspicuous among Europeans fascinated by the biodiversity and native peoples of an incomparably vast basin stretching from the Andes to the Atlantic, from the Guiana Highlands to Peru and Bolivia, from Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador to the mouth of the Amazon at the Brazilian equator. Exactly two thousand years ago, in the summer of the year 9, a decisive victory of Germanic tribes over occupying Roman legions took place in a forest near a swamp. With that the Roman Empire began its final decline, and some would say the event was the seed of germination for the eventual German nation. -

Asia Pacific Economic Forum), Asia Pacific Economic Forum (APEC), 21,26 21,26 Argentina

Index A Agroprombank, 213 Argentine Congress to the Central Bank Anchor currency, 51 Charter Act (CBCA), 185 Euro as, 52 Articles of Termination mark as, 41, 43, 50 (Czechoslovakia),234 APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Forum), Asia Pacific Economic Forum (APEC), 21,26 21,26 Argentina. see also Argentine banking Association of South East Asian Nations panic (1994-1995) (ASEAN),21 fmancial history of, 183-184 Asymmetric information theory, 150- foreign reserves/monetary liabilities, 156 192 adverse selection, 150 Argentine banking panic (1994-1995), application of, 156-172 183-207,337. see also factors leading to crisis, 151-156 Convertibility Plan (Argentina) financial crisis defined, 151 banks, nominal capital asset ratios for, moral hazard, 151 202 Austria, 33, 42, 96 developments leading to (1994), 184, Azores conference (1972), 96 192-206 failing/merging banks, characteristics of, 203-206 B interaction between policy response/shock, 19 I Bahrain, 124 international interest rate evolution, Baker, James, 14 192-200 Balance sheets minimum capital regulations/new asset market effects on, 152-155 provisioning rules, 200-203 in bank panics, 155-156 Argentine Brady Bonds, 192-193 in Mexican peso crisis, 158, 159, 166 retail bank (Argentina), 196 344 INDEX wholesale bank (Argentina), 195 Basle Capital Adequacy Accord (1988), Baldwin, Robert, 281 103,219,341 Banca d'Italia, 263 Basle Committee for Banks Regulation, Banco de Mexico, 161, 166,312 188 Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Basle Committee of Banking 15 Supervisors, 218 Annual report (1995), 341 Basle-Nyborg Agreement (1987), 45, 64 in Mexico, 3 13 Belgium, 96 in Russia, 218 in EMS, 118 Banking system (Russia), 339. -

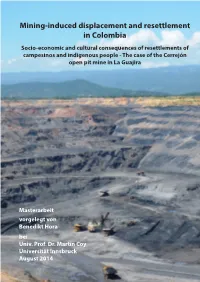

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

A History of Merchant, Central and Investment Banking Learning

Chapter 2: A History of Merchant, Central and Investment Banking Learning Objectives: To apply the history and evolution of money and banking to comprehension of existing systems To diagnose and calculate seniorage and debasement To recount how conditions drawn from history led to today's instruments and institutions To examine how economic problems lead to banking and capital market innovations To describe how money and banking integrated into the many economies over thousands of years To summarize the many artistic, literary, technological and scientific achievements that were funded or otherwise facilitated by banking To recognize the problems associated with usury in religious, social and economic contexts To express how academic, exploration, technological, trading, religious and other cultural developments contributed to the practice of banking A. Early History of Money In Chapter 1, we briefly discussed the economic roles of a number of types of financial institutions along with their origins. In this chapter, we discuss in greater detail the history of money and banking, beginning with the early history of money and extending through the advent of modern banking in the early 20th century. In later chapters, we will discuss the repeated occurrence and consequences of banking crises and development of banking regulation from a historical perspective. Commodity and Representative Money The earliest forms of money tended to have alternative intrinsic value as commodities. For example, grain-money has been used since the dawn of agriculture. Neolithic peoples in what is now China are believed to have used cowrie (sea snail) shells as money perhaps as long ago as 4,500 years. -

Die Konquista Der Augsburger Welser-Gesellschaft In

Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 13 I. Die Statthalterschaft der 1Ä/relser in Venezuela 1528—1556: Rekonstruktion der Ereignisse 1. Die Rahmenbedingungen des Unternehmens 37 1. 1 Die Interessen der spanischen Krone 37 1. 2 Die <Asientos> — Kronverträge zur Eroberung Amerikas 40 1. 3 Der Weg der Welser-Gesellschaft ins Venezuela-Unternehmen 42 1. 4 Die <Venezuela-Verträge > 51 1. 5 Zum <Chile-Projekt> der Fugger 55 1. 6 Die wirtschaftliche Planung des Venezuela-Unternehmens 57 1. 7 Die Welser-Faktoren in Übersee. Ihre Herkunft und die Auswirkungen ihrer Stellung in der Gesellschaft auf das Venezuela-Unternehmen , 59 2. In Venezuela: Die Orientierungsphase 1529-1531 69 2. 1 Die Etablierung des Welser-Gouvernements und die Gründung von Coro 69 2. 2 Die Erkundung des Westens — die erste Entrada Ambrosius Alfingers 1529/30 71 2. 3 Die Gründung Maracaibos , 73 2. 4 Zum Verständnis der Stadtgründungen während der Konquista 74 2. 5 Die Erkundung des Südens der Provinz ~~ die erste Entrada Nikolaus Federmanns 1530/31 76 2. 6 Die Sabotierung des Montanprojekts 79 2. 7 Aus dem Alltag der Konquista 82 2. 7. 1 <Freundschaft>: Das Verhältnis zwischen Konquistadoren und Eingeborenen auf den Entradas 82 2. 7. 2. Die Versklavung von Indianern 84 2. 8 Die zweite Entrada Alfingers, Teil 1: Die Invasion der Kordilleren 1531-1532. 89 2. 8. 1. Die Plünderung des <Tals der Pacabueyes> 90 2. 8. 2. Die Spur nach <Cundin> 93 Inhaltsverzeichnis 3. Die Suche nach dem <Goldland > Cundinamarca: 1532—1539 ... 97 3. 1 Cundinamarca 97 3. 1. 1 Die Muisca-Kultur 97 3. 1. 2 (Not to see the sun> — der Gottkönig El Dorado und das Ritual der Vergoldung 99 3. -

Center 34 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center34

CENTER 34 CENTER34 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR IN STUDY THE ADVANCED VISUAL ARTS CENTER34 CENTER34 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Record of Activities and Research Reports June 2013 – May 2014 Washington, 2014 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, DC Mailing address: 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, Maryland 20785 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 Fax: (202) 842-6733 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nga.gov/casva Copyright © 2014 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law, and except by reviewers from the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Produced by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts and the Publishing Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington ISSN 1557-198x (print) ISSN 1557-1998 (online) Editor in Chief, Judy Metro Deputy Publisher and Production Manager, Chris Vogel Series Editor, Peter M. Lukehart Center Report Coordinator, Hayley Plack Managing Editor, Cynthia Ware Design Manager, Wendy Schleicher Assistant Production Manager, John Long Assistant Editor, Lisa Wainwright Designed by Patricia Inglis, typeset in Monotype Sabon and Helvetica Neue by BW&A Books, Inc., and printed on McCoy Silk by C&R Printing, Chantilly, Virginia Frontispiece: Members of Center, December 17, 2013 -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 11, 2014 Index Hatzopoulos Marios https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 Copyright © 2014 To cite this article: Hatzopoulos, M. (2014). Index. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 11, I-XCII. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX, VOLUMES I-X Compiled by / Compilé par Marios Hatzopoulos http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX Aachen (Congress of) X/161 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- Abadan IX/215-216 Lettres, Paris II/67, 71, 109; III/178; Abbott (family) VI/130, 132, 138-139, V/79; VI/54, 65, 71, 107; IX/174-176 141, 143, 146-147, 149 Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Abbott, Annetta VI/130, 142, 144-145, Belles-Lettres de Toulouse VI/54 147-150 Academy of France I/224; V/69, 79 Abbott, Bartolomew Edward VI/129- Acciajuoli (family) IX/29 132, 136-138, 140-157 Acciajuoli, Lapa IX/29 Abbott, Canella-Maria VI/130, 145, 147- Acciarello VII/271 150 Achaia I/266; X/306 Abbott, Caroline Sarah VI/149-150 Achilles I/64 Abbott, George Frederic (the elder) VI/130 Acropolis II/70; III/69; VIII/87 Abbott, George Frederic (the younger) Acton, John VII/110 VI/130, 136, 138-139, 141-150, 155 Adam (biblical person) IX/26 Abbott, George VI/130 Adams, -

Gold in Der Lagune Von KAREN ANDRESEN

El-Dorado-Floß als zeitgenössische Goldschmiede- arbeit, ausgestellt im Museo del Oro in Bogotá An der Eroberung Lateinamerikas durch die spanische Krone waren auch Deutsche beteiligt, die Venezuela ausbeuten wollten – mit verheerenden Folgen für die Indios. Gold in der Lagune Von KAREN ANDRESEN m Ende war es die Gier Aus den sechs Monaten wurden fünf 16. Jahrhunderts fand der Spanier Her- nach dem Gold, die ihnen Jahre, ohne dass von Hutten größere nán Cortés in Mexiko kostbare Edelme- allen zum Verhängnis Reichtümer fand. Im Mai 1546 ermor- talle. Einen Teil davon schickte er 1522 an wurde. Dem Augsburger dete ihn ein spanischer Rivale um Macht den Hof Karls V., was Begehrlichkeiten Handelshaus der Welser und Beute. quer durch Europa weckte. Der alte Kon- Aebenso wie dessen Vertretern in der Oder Ambrosius Dalfinger, erster tinent geriet in Goldgräberstimmung, Neuen Welt. Gouverneur der Welser in Venezuela, Amerika galt fortan als Paradies für lu- Philipp von Hutten etwa. Der fränki- getötet auf einem Eroberungszug durch krative Eroberungszüge. Frankreich war sche Reichsritter machte sich 1541 im den Giftpfeil eines Indios. interessiert und Portugal auch. Auftrag der Augsburger auf die Suche Oder Nikolaus Federmann, der wohl Um den Konkurrenten zuvorzukom- nach dem sagenumwobenen Schatz von findigste der Welserschen Schatzsucher, men, beschloss die spanische Krone, sich El Dorado. „Ain Furer“, schrieb er vor gestorben einsam und verbittert in ei- das gewinnträchtige Land so schnell wie der Reise an seinen Bruder Moritz, habe nem Kerker im spanischen Valladolid. möglich untertan zu machen. Die Sache sich „beym Kopf“ verpflichtet, „uns in- Dabei hatte alles mit guten Nachrich- hatte allerdings einen Haken: Karl V. -

Colombia Curriculum Guide 090916.Pmd

National Geographic describes Colombia as South America’s sleeping giant, awakening to its vast potential. “The Door of the Americas” offers guests a cornucopia of natural wonders alongside sleepy, authentic villages and vibrant, progressive cities. The diverse, tropical country of Colombia is a place where tourism is now booming, and the turmoil and unrest of guerrilla conflict are yesterday’s news. Today tourists find themselves in what seems to be the best of all destinations... panoramic beaches, jungle hiking trails, breathtaking volcanoes and waterfalls, deserts, adventure sports, unmatched flora and fauna, centuries old indigenous cultures, and an almost daily celebration of food, fashion and festivals. The warm temperatures of the lowlands contrast with the cool of the highlands and the freezing nights of the upper Andes. Colombia is as rich in both nature and natural resources as any place in the world. It passionately protects its unmatched wildlife, while warmly sharing its coffee, its emeralds, and its happiness with the world. It boasts as many animal species as any country on Earth, hosting more than 1,889 species of birds, 763 species of amphibians, 479 species of mammals, 571 species of reptiles, 3,533 species of fish, and a mind-blowing 30,436 species of plants. Yet Colombia is so much more than jaguars, sombreros and the legend of El Dorado. A TIME magazine cover story properly noted “The Colombian Comeback” by explaining its rise “from nearly failed state to emerging global player in less than a decade.” It is respected as “The Fashion Capital of Latin America,” “The Salsa Capital of the World,” the host of the world’s largest theater festival and the home of the world’s second largest carnival. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9330527 Among the cannibals and Amazons: Early German travel literature on the New World Dunlap, Samuel Roy, Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, 1992 Copyright ©1992 by Dunlap, Samuel Roy. -

Narrative and Geology As Advocates for Science Education of Local Residents and Tourists – the El Dorado Case Study

Narrative and Geology as Advocates for Science Education of Local Residents and Tourists – the El Dorado Case Study Master’s thesis by Markus Lindewald Åbo Akademi University 2019 Geology and mineralogy, Faculty of Science and Engineering Abstrakt Denna avhandling är en fallstudie om El Dorado, ”Den gyllene mannen”. Avhandlingen redogör för de historiska händelser som ledde till erövringen av dagens Colombia och till upptäckten av Guatavitasjön, vars geologiska ursprung, trots åtskilliga vetenskapliga utredningar, fortfarande kvarstår som en gåta i den akademiska världen. I avhandlingen ingår två huvudsakliga studier som redogör för 1) författarens hypotes om ett möjligt vulkaniskt ursprung i form av en Maar-Diatreme, vilket förklarar Guatavitasjöns kraterlika form och 2) en opinionsundersökning om publikens intresse för olika geologiska hypoteser som redogör för Guatavitasjöns geologiska ursprung. Guatavitasjöns kraterlika form, dess inre och yttre vinklar, och förekomsten av det möjligtvis tuffitiska materialet som påträffats vid foten av kraterns nordöstra sida och som även analyserats kan överensstämma med definitionen av en Maar-Diatreme. Tecken på relativt färsk vulkanism i regionen och en dokumenterad beskrivning av sjöns perfekta platta botten i samband med dräneringen av Lake Guatavita år 1910, antyder ytterligare på teorin om en eventuell Maar-Diatreme. I studiens opinionsundersökning konstaterades att ungefär 90 procent av lokalbefolkningen och cirka 86 procent av besökande turister var intresserade av en vetenskaplig förklaring till Guatavitasjöns ursprung och poängterade vikten av en sådan utredning. Denna fallstudie om El Dorado framhäver allmänhetens intresse för geologisk kunskap och behandlar potentialen att förmedla vetenskaplig inblick i berättandeform i syftet att nå en publik bestående av turister och lokala lekmän.