The Changing Dynamics of Kurdish Politics in the Middle East About the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

Borders As Ethnically Charged Sites: Iraqi Kurdistan Border Crossings, 1995-2006

BORDERS AS ETHNICALLY CHARGED SITES: IRAQI KURDISTAN BORDER CROSSINGS, 1995-2006 Diane E. King Department of Anthropology University of Kentucky ABSTRACT: In this article, I use border crossings between Syria, Turkey, and Iraq during the period from 1995 to 2006 to examine the modern state, identity, and territory at border crossing points. Borderlands represent a site where the core powers of states can display the reach, scope, face, and preferred expressions of their identities. Border crossing points between modern states that make strong ethnolinguistic and/or ethnosectarian identity assertions, as do the states on which I focus here, are often charged sites where the state may seek to impose a certain identity category on an individual, an identity that the individual may or may not claim. Kurdistan, the non-state area recognized by Kurds as their ethnic/national home, arcs across the states, and most of the people meeting at the borders are ethnically Kurdish. The state may deny hybridity, or use hybridity, especially multilingualism, for its own purposes. Ethnolinguistic and other collective identity categories in Syria, Turkey, and Iraq are assigned according to patrilineal descent, which means that singular categories are passed from one gener- ation to the next. These categories are made much less malleable by their reliance on descent claims through one parent. In such a 51 ISSN 0894-6019, © 2019 The Institute, Inc. 52 URBAN ANTHROPOLOGY VOL. 48(1,2), 2019 milieu, ethnic identities may be a factor to a greater degree than if their state systems allowed for more ethnic flexibility and hybridity. Introduction In this article I use some encounters I had at border crossing points between Syria, Turkey and Iraq in the years from 1995 to 2006 to think questions of collective identity, territoriality, and boundaries in modern states. -

Nation, Bordering and Identity on the Border Between Turkey and Iraq

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ by Bilal GORENTAS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SEPTEMBER 2016 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ BILAL GORENTAS This thesis explores the impact of the border between Turkey and Iraq on Kurdish identity. Since the demarcation of the border in 1926, both Turkey and Iraq have struggled to accommodate their Kurdish citizens into their common national communities. -

Westminsterresearch Language Ideologies and Identities in Kurdish

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Language ideologies and identities in Kurdish heritage language classrooms in London Yilmaz, B. This is an author's accepted manuscript of an article published in the International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 253 (86), pp. 173-200, 2018. The final definitive version is available online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2018-0030 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Language ideologies and identities in Kurdish heritage language classrooms in London Abstract This article investigates the way that Kurdish language learners construct discourses around identity in two language schools in London. It focuses on the values that heritage language learners of Kurdish-Kurmanji attribute to the Kurmanji spoken in the Bohtan and Maraş regions of Turkey. Kurmanji is one of the varieties of Kurdish that is spoken mainly in Turkey and Syria. The article explores the way that learners perceive the language from the Bohtan region to be ‘good Kurmanji’, in contrast to the ‘bad Kurmanji’ from the Maraş region. Drawing on ethnographic data collected from community-based Kurdish-Kurmanji heritage language classes for adults in South and East London, I illustrate how distinctive lexical and phonological features such as the sounds [a:] ~ [ɑ:] and [ɑ]/ [æ] ~ [a:] are associated with regional (and religious) identities of the learners. -

The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1979 The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey Kathleen Palmer Ertur Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ertur, Kathleen Palmer, "The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey" (1979). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2890. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2885 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. l . 1 · AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF ·Kathleen Palmer Ertur for the Master of Arts in Political Science presented February 20, 1979· I I I Title: The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey. 1 · I APPROVED EY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: ~ Frederick Robert Hunter I. The purpose of this thesis is to illustrate the situation of the Kurdish minority in Turkey within the theoretical parameters of political integration. The.problem: are the Kurds in Turkey politically integrated? Within the definition of political develop- ment generally, and of political integration specifically, are found problem areas inherent to a modernizing polity. These problem areas of identity, legitimacy, penetration, participatio~ and distribution are the basis of analysis in determining the extent of political integration ·for the Kurds in Turkey. When .thes_e five problem areas are adequate~y dealt with in order to achieve the goals of equality, capacity and differentiation, political integration is achieved. -

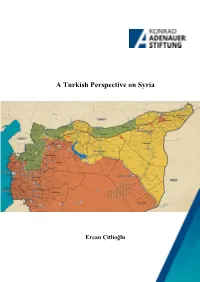

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Maps into Nations: Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society by Zeynep N. Kaya A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2012. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 77,786 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Matthew Whiting. 2 Anneme, Babama, Kardeşime 3 Abstract This thesis explores how Kurdish nationalists generate sympathy and support for their ethnically-defined claims to territory and self-determination in international society and among would-be nationals. It combines conceptual and theoretical insights from the field of IR and studies on nationalism, and focuses on national identity, sub-state groups and international norms. -

Enclave Governance: How to Circumvent the Assad Regime and Safeguard Syria’S Future

Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper Number 30, December 2020 Enclave Governance: How to Circumvent the Assad Regime and Safeguard Syria’s Future Ranj Alaaldin ENCLAVE GOVERNANCE: HOW TO CIRCUMVENT THE ASSAD REGIME AND SAFEGUARD SYRIA’S FUTURE Ranj Alaaldin The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2020 Brookings Institution THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 III. Current Challenges to Stability and Peacebuilding ...............................................8 -

The Kurds As Parties to and Victims of Conflicts in Iraq Inga Rogg and Hans Rimscha Inga Rogg Is Iraq Correspondent for the Neue Zu¨Rcher Zeitung and NZZ Am Sonntag

Volume 89 Number 868 December 2007 The Kurds as parties to and victims of conflicts in Iraq Inga Rogg and Hans Rimscha Inga Rogg is Iraq correspondent for the Neue Zu¨rcher Zeitung and NZZ am Sonntag. She graduated in cultural anthropology and Ottoman history and has done extensive research in the Kurdish region. Hans Rimscha graduated in Islamic studies and anthropology, worked with humanitarian assistance operations in Iraq in the 1990s and is the author of various publications on Middle East issues. Abstract After decades of fighting and suffering, the Kurds in Iraq have achieved far-reaching self-rule. Looking at the history of conflicts and alliances between the Kurds and their counterparts inside Iraq and beyond its borders, the authors find that the region faces an uncertain future because major issues like the future status of Kirkuk remain unsolved. A federal and democratic Iraq offers a rare opportunity for a peaceful settlement of the Kurdish question in Iraq – and for national reconciliation. While certain groups and currents in Iraq and the wider Arab world have to overcome the notion that federalism equals partition, the Kurds can only dispel fears about their drive for independence if they fully reintegrate into Iraq and show greater commitment to democratic reforms in the Kurdistan Region. ‘‘This is the other Iraq’’, says a promotion TV spot regularly broadcast on Al Arrabiyeh TV, ‘‘The people of Iraqi Kurdistan invite you to discover their peaceful region, a place that has practised democracy for over a decade, a place where universities, markets, cafe´s and fairgrounds buzz with progress and prosperity and where people are already sowing the seeds of a brighter future.’’1 A regional government After decades of internal and regional conflict, the large-scale destruction and persecution of the Kurdish population, and periods of bitter infighting between 823 I. -

The Kurds? Lisa Adeli, University of Arizona Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Who Are the Kurds? Lisa Adeli, University of Arizona Center for Middle Eastern Studies Where: Kurds live in a mountainous area of eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, and small parts of northern Syria and Armenia. “Kurdistan” (which is not a recognized country but divided amount the countries listed above) is an area of 230,000 square miles, an area about as big as Texas. See the map at: http://ericblackink.minnpost.com/wp- content/uploads/oct._07/where_kurds_predominate.jpg Who: Kurds are predominantly Indo-European and speak a language in the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. In other words, Kurdish is related to Persian, not to Arabic or Turkish. Most are Sunni Muslims. How many: Authorities disagree completely on the issue of how many Kurds there are, giving figures from 15-27 million. Why the discrepancy? For one thing, it can be hard to determine ethnicity, especially for people of mixed heritage or who live/work amid the majority population group. Mostly, however, the problems come because of political reasons. The governments of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey usually cite lower numbers of Kurds because they have in interest in downplaying the numbers of its minority populations and/or because Kurdish citizens of these countries may not identify themselves as Kurds for fear of discrimination. Kurdish sources usually give much higher numbers, which may be inflated to increase their political clout. Finally, Kurds have frequently become refugees, moving from one country to another to escape war or persecution. Therefore, the number of Kurds in a particular country may vary greatly from one year to the next, making overall numbers more difficult to calculate. -

Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language Sevda Arslan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Arslan, Sevda, "Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language" (2015). Master's Theses. 620. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/620 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE POLICY IN TURKEY AND ITS EFFECT ON THE KURDISH LANGUAGE by Sevda Arslan A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Political Science Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D., Chair Kristina Wirtz, Ph.D. Mahendra Lawoti, Ph.D. LANGUAGE POLICY IN TURKEY AND ITS EFFECT ON THE KURDISH LANGUAGE Sevda Arslan, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 For many decades the Kurdish language was ignored and banned from public use and Turkish became the lingua franca for all citizens to speak. This way, the Turkish state sought to create a nation-state based on one language and attempted to eliminate the use of other languages, particularly Kurdish, through severe regulations and prohibitions. -

Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society

Syria’s Kurds This book is a decisive contribution to the study of Kurdish history in Syria since the Mandatory period (1920–1946) up to the present. Avoiding an essentialist approach, Jordi Tejel provides fine, complex and some- times paradoxical analysis of the articulation between tribal, local, regional, and national identities, on one hand, and the formation of a Kurdish minority aware- ness vis-à-vis the consolidation of Arab nationalism in Syria, on the other hand. Using unpublished material, in particular concerning the Mandatory period (French records and Kurdish newspapers) and social movement theory, Tejel analyses the reasons behind the Syrian “exception” within the Kurdish political sphere. In spite of the exclusion of Kurdishness from the public sphere, especially since 1963, Kurds of Syria have avoided a direct confrontation with the central power, most Kurds opting for a strategy of ‘dissimulation’, cultivating internally the forms of identity that challenge the official ideology. The book explores the dynamics leading to the consolidation of Kurdish minority awareness in contem- porary Syria; an ongoing process that could take the form of radicalization or even violence. While the book offers a rigorous conceptual approach, the ethnographic mate- rial makes it a compelling read. It will not only appeal to scholars and students of the Middle East, but to those interested in history, ethnic conflicts, nationalism, social movement theories, and many other related issues. Jordi Tejel is a Ph.D. in History (University of Fribourg, Switzerland) and Sociology (Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales-EHESS, Paris). He is currently a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the EHESS, Paris.