The Kurds in the Spotlight: Local and Regional Challenges1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Conflict Profile

MODERN CONFLICTS: CONFLICT PROFILE Iraq (Kurds) (1961 - 1996) The Kurds are an ethnic group in northern Iraq and neighboring Turkey and Iran. There are longstanding conflicts between the Kurds and the governments of all three countries (see also Turkey-Kurds conflict profile). Sustained warfare between the Iraqi government and Kurdish fighters dates from 1961. In the first phase of the war, the Iraqi government controlled the cities and major towns, while Kurdish peshmerga fighters controlled the mountains. Iraq used aerial bombardment while the Kurds relied mainly on guerrilla tactics. An agreement that would have granted autonomy to the Kurds in was almost signed in >> MODERN CONFLICTS 1970, but the two parties could not agree to the division of oil rights and the fighting HOME PAGE resumed. With increased support from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and the Iranian government, the Kurds escalated the war. In 1975, when the CIA and Iran cut off >> CONFLICTS MAP their support, the Kurdish forces were significantly weakened. This phase of the war was >> CONFLICTS TABLE characterized by mass displacements, summary executions, and other gross human rights >> PERI HOME PAGE violations. In 1979, when Saddam Hussein became president of Iraq, he intensified the repression against the Kurds. Though Kurds resisted, large-scale fighting did not resume until the mid-1980s when Iran, now fighting its own war with Iraq, renewed support for the peshmerga. In 1987, Saddam Hussein appointed his cousin, General Ali Hassan al-Majid, to subdue the Kurds. “Chemical Ali,” as he came to be known because of his use of chemical weapons, launched the Anfal campaign that resulted in the deaths of approximately 100,000 Kurds, the displacement of hundreds of thousands of others, and the destruction of more than 2,000 Kurdish villages. -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

The Contemporary Roots of Kurdish Nationalism in Iraq

THE CONTEMPORARY ROOTS OF KURDISH NATIONALISM IN IRAQ Introduction Contrary to popular opinion, nationalism is a contemporary phenomenon. Until recently most people primarily identified with and owed their ultimate allegiance to their religion or empire on the macro level or tribe, city, and local region on the micro level. This was all the more so in the Middle East, where the Islamic umma or community existed (1)and the Ottoman Empire prevailed until the end of World War I.(2) Only then did Arab, Turkish, and Iranian nationalism begin to create modern nation- states.(3) In reaction to these new Middle Eastern nationalisms, Kurdish nationalism developed even more recently. The purpose of this article is to analyze this situation. Broadly speaking, there are two main schools of thought on the origins of the nation and nationalism. The primordialists or essentialists argue that the concepts have ancient roots and thus date back to some distant point in history. John Armstrong, for example, argues that nations or nationalities slowly emerged in the premodern period through such processes as symbols, communication, and myth, and thus predate nationalism. Michael M. Gunter* Although he admits that nations are created, he maintains that they existed before the rise of nationalism.(4) Anthony D. Smith KUFA REVIEW: No.2 - Issue 1 - Winter 2013 29 KUFA REVIEW: Academic Journal agrees with the primordialist school when Primordial Kurdish Nationalism he argues that the origins of the nation lie in Most Kurdish nationalists would be the ethnie, which contains such attributes as considered primordialists because they would a mythomoteur or constitutive political myth argue that the origins of their nation and of descent, a shared history and culture, a nationalism reach back into time immemorial. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

The Kurdish Nationalist Movement and External Influences

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1980-12 The Kurdish nationalist movement and external influences Disney, Donald Bruce, Jr. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/17624 '";. Vi , *V ^y NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE KURDISH NATIONALIST MOVEMENT AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES by Donald Bruce Disney, Jr. December 1980 The sis Advisor: J. W. Amos, II Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited T19 «—,rob J Unclassified "wi.fy * N°* StCUHlTY CLASSIFICATION r>* THIS »>GI '•*>•« D«t Knlmrmd) READ INSTRUCTIONS REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM •f*OAT NUMlf* 2. OOVT ACCCUION MO. J MKCl»lCNT'S CATALOG NUMBER. 4 TiTlE ,«.*Ju »mH) s. TY*e of neponT * rewoo covcncd The Kurdish Nationalist Movement Master's Thesis; and External Influences December 1980 * »I»ro»l»INQ owe. «I»OKT NUMIIR 7. AuTmO*><*> • contract o« chant HumUtnf) Donald Bruce Disney, Jr., LCDR, USN * RfBFORMINO OWOANI2ATION NAME AND >QD*tii tO. *«OG*AM CLEMENT. RBOjECT. T as* AREA * «OMK UNIT NUDUM Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, California 93940 M CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME ANO ADDRESS 12. MFOUT DATE Naval Postgraduate School December, 1980 Monterey, California 93940 II. MUMBER O' WAGES 238 TT MONITORING AGENCY NAME A AOORESSfll if>'M*ml Ifmm Controlling Ottlc*) It- SICURITY CLASS. <al Iftlm report) Naval Postgraduate School Unclassified Monterey, California 93940 Im DECLASSIFICATION/ DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE l«. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT (of Ihlt *•»•»!) Approved for public release; distribution unlimited 17 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT at (»• •*•„•«( rnrnfm** In #I»c* 20, // dittfmt rrmm Mf rt) IE. SUFFLCMCNTARY NOTES '» KEY *O*0l (Continue em remem »!<*• It r\eceeeiy em* itemttty m, ilect IHMHMMP Kurds, Kurdish Nationalism, Kurdish Revolts, Kurdish Political Parties, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, Sheikh Ezzedin, Abdul Rahman Qassemlu, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, UK, U.S., U.S.S.R., Israel, PLO, Armenians 20. -

Borders As Ethnically Charged Sites: Iraqi Kurdistan Border Crossings, 1995-2006

BORDERS AS ETHNICALLY CHARGED SITES: IRAQI KURDISTAN BORDER CROSSINGS, 1995-2006 Diane E. King Department of Anthropology University of Kentucky ABSTRACT: In this article, I use border crossings between Syria, Turkey, and Iraq during the period from 1995 to 2006 to examine the modern state, identity, and territory at border crossing points. Borderlands represent a site where the core powers of states can display the reach, scope, face, and preferred expressions of their identities. Border crossing points between modern states that make strong ethnolinguistic and/or ethnosectarian identity assertions, as do the states on which I focus here, are often charged sites where the state may seek to impose a certain identity category on an individual, an identity that the individual may or may not claim. Kurdistan, the non-state area recognized by Kurds as their ethnic/national home, arcs across the states, and most of the people meeting at the borders are ethnically Kurdish. The state may deny hybridity, or use hybridity, especially multilingualism, for its own purposes. Ethnolinguistic and other collective identity categories in Syria, Turkey, and Iraq are assigned according to patrilineal descent, which means that singular categories are passed from one gener- ation to the next. These categories are made much less malleable by their reliance on descent claims through one parent. In such a 51 ISSN 0894-6019, © 2019 The Institute, Inc. 52 URBAN ANTHROPOLOGY VOL. 48(1,2), 2019 milieu, ethnic identities may be a factor to a greater degree than if their state systems allowed for more ethnic flexibility and hybridity. Introduction In this article I use some encounters I had at border crossing points between Syria, Turkey and Iraq in the years from 1995 to 2006 to think questions of collective identity, territoriality, and boundaries in modern states. -

Nation, Bordering and Identity on the Border Between Turkey and Iraq

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ by Bilal GORENTAS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SEPTEMBER 2016 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL, HUMAN AND MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES Geography and Environment Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy NATION, BORDERING AND IDENTITY ON THE BORDER BETWEEN TURKEY AND IRAQ BILAL GORENTAS This thesis explores the impact of the border between Turkey and Iraq on Kurdish identity. Since the demarcation of the border in 1926, both Turkey and Iraq have struggled to accommodate their Kurdish citizens into their common national communities. -

Westminsterresearch Language Ideologies and Identities in Kurdish

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Language ideologies and identities in Kurdish heritage language classrooms in London Yilmaz, B. This is an author's accepted manuscript of an article published in the International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 253 (86), pp. 173-200, 2018. The final definitive version is available online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2018-0030 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Language ideologies and identities in Kurdish heritage language classrooms in London Abstract This article investigates the way that Kurdish language learners construct discourses around identity in two language schools in London. It focuses on the values that heritage language learners of Kurdish-Kurmanji attribute to the Kurmanji spoken in the Bohtan and Maraş regions of Turkey. Kurmanji is one of the varieties of Kurdish that is spoken mainly in Turkey and Syria. The article explores the way that learners perceive the language from the Bohtan region to be ‘good Kurmanji’, in contrast to the ‘bad Kurmanji’ from the Maraş region. Drawing on ethnographic data collected from community-based Kurdish-Kurmanji heritage language classes for adults in South and East London, I illustrate how distinctive lexical and phonological features such as the sounds [a:] ~ [ɑ:] and [ɑ]/ [æ] ~ [a:] are associated with regional (and religious) identities of the learners. -

The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1979 The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey Kathleen Palmer Ertur Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ertur, Kathleen Palmer, "The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey" (1979). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2890. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2885 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. l . 1 · AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF ·Kathleen Palmer Ertur for the Master of Arts in Political Science presented February 20, 1979· I I I Title: The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey. 1 · I APPROVED EY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: ~ Frederick Robert Hunter I. The purpose of this thesis is to illustrate the situation of the Kurdish minority in Turkey within the theoretical parameters of political integration. The.problem: are the Kurds in Turkey politically integrated? Within the definition of political develop- ment generally, and of political integration specifically, are found problem areas inherent to a modernizing polity. These problem areas of identity, legitimacy, penetration, participatio~ and distribution are the basis of analysis in determining the extent of political integration ·for the Kurds in Turkey. When .thes_e five problem areas are adequate~y dealt with in order to achieve the goals of equality, capacity and differentiation, political integration is achieved. -

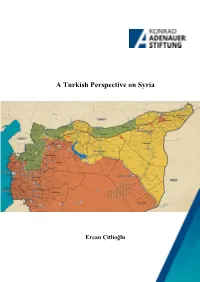

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Maps into Nations: Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society by Zeynep N. Kaya A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2012. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 77,786 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Matthew Whiting. 2 Anneme, Babama, Kardeşime 3 Abstract This thesis explores how Kurdish nationalists generate sympathy and support for their ethnically-defined claims to territory and self-determination in international society and among would-be nationals. It combines conceptual and theoretical insights from the field of IR and studies on nationalism, and focuses on national identity, sub-state groups and international norms.