The Piano Sonata in Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monograph-Ana Catalina Ramirez

COSTA RICAN COMPOSER CARLOS ESCALANTE MACAYA AND HIS CONCERTO FOR CLARINET AND STRINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Ana Catalina Ramírez Castrillo May, 2014 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Cynthia Folio, Advisory Chair, Music Studies Department (Music Theory) Dr. Charles Abramovic, Piano Department, Keyboard Department (Piano) Dr. Emily Threinen, Instrumental Studies Department (Winds and Brass) Dr. Stephen Willier, Music Studies Department (Music History) ABSTRACT The purpose of this monograph is to promote Costa Rican academic music by focusing on Costa Rican composer Carlos Escalante Macaya and his Concerto for Clarinet and Strings (2012). I hope to contribute to the international view of Latin American composition and to promote Costa Rican artistic and cultural productions abroad with a study of the Concerto for Clarinet and Strings (Escalante’s first venture into the concerto genre), examining in close detail its melodic, rhythmic and harmonic treatment as well as influences from different genres and styles. The monograph will also include a historical context of Costa Rican musical history, a brief discussion of previous important Costa Rican composers for the clarinet, a short analysis of the composer’s own previous work for the instrument (Ricercare for Solo Clarinet) and performance notes. Also, in addition to the publication and audio/video recording of the clarinet concerto, this document will serve as a resource for clarinet soloists around the world. Carlos Escalante Macaya (b. 1968) is widely recognized in Costa Rica as a successful composer. His works are currently performed year-round in diverse performance venues in the country. -

University of Pittsburgh Winter 2012 • 71 Center for Latin American Studies

Winter 2012 • 71 CLASicos Center for Latin American Studies University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh 2 The Latin American CLASicos • Winter 2012 Archaeology Program Latin America has been the principal geographical focus of archaeology at the University of Pittsburgh over the last two decades. Administered by the Department of Anthropolo- gy, with the cooperation and support of CLAS, the Latin American Archaeology Pro- gram involves research, training, and publication. Its objective is to maintain an interna- tional community of archaeology graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. This objective is promoted in part through fellowships for outstanding graduate students to study any area of Latin American prehistory. Many of these fellowships are awarded to students from Latin America (nearly half of the students in the program). The commit- ment to Latin American archaeology also is illustrated by collaborative ties with numer- ous Latin American institutions and by the bilingual publication series, which makes the results of primary field research available to a worldwide audience. The Latin American Archaeology Publications Program publishes the bilingual From 1997—Left to right: Latin American Archaeology Fellows Hope Henderson (US), María Auxiliadora Cordero (Ecuador), Ana María Boada (Colombia), [Professor Dick Drennan], and Rafael Gassón (Venezuela). Memoirs in Latin American Archaeology and Latin American Archaeology Reports, co-publishes the collaborative series Arqueología de México, and distributes internationally volumes on Latin American archaeology and related subjects from more than eighteen publishers worldwide. The Latin American Archaeology Database is on line, with datasets that complement the Memoirs and Reports series as well as disserta- tions and other publications. -

A Plutón Para Saxo Alto Y Piano

Fémina Clásica inicia hoy su segunda andadura después del exitoso primer concierto el año pasado. Asunto de dos, concierto de todos, pretende ser una metáfora de la concordia y la ilusión con que se inician las relaciones entre dos personas, pero también como un reclamo a la responsabilidad que todos debemos tener ante las consecuencias que puedan generar las discordias y los actos de violencia en la pareja, mayoritariamente contra la mujer. La buena influencia de la música puede contribuir a que las relaciones entre dos personas no generen violencia; y con este propósito las compositoras e intérpretes que participan han querido contribuir para que algún día, más temprano que tarde, el placer de disfrutar la música reemplace al Día Internacional contra la Violencia de Género. Por eso, depende de cada uno de nosotros convertir el asunto de dos en un concierto de todos. El concierto fémina Clásica’09 y su grabación en directo para un disco promocional se enmarcan dentro de las actividades de apoyo al Día Internacional contra la Violencia de Género. 05 I II MARÍA DOLORES MALUMBRES: A Plutón (2007) para saxo alto y piano CRUZ LÓPEZ DE REGO: Tríptico cubano para soprano y piano (1994) Manuel Miján, saxo alto / Sebastián Mariné, piano Consejo, texto: Rafael Estenger Disfraz, texto: Raúl González de Cascorro SOFÍA MARTÍNEZ: La liberación del círculo para violín y viola (2009) * Y te busqué por pueblos, texto: José Martí Guacimara Alonso, violín / Alejandro Garrido, viola Celia Alcedo, soprano / Ana Vega Toscano, piano BEATRIZ ARZAMENDI: Prismas -

TRAINED ABROAD: a HISTORY of MULTICULTURALISM in COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by I

Trained Abroad: A History of Multiculturalism in Costa Rican Vocal Music Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ortiz Castro, Ivette Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 10:27:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/621142 TRAINED ABROAD: A HISTORY OF MULTICULTURALISM IN COSTA RICAN VOCAL MUSIC by Ivette Ortiz Castro _______________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Ivette Ortiz-Castro, titled Trained abroad: a history of multiculturalism in Costa Rican vocal music and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Kristin Dauphinais ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 Jay Rosenblatt ____________________________________________________________________________ Date: 07/18/16 William Andrew Stuckey Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Ensemble Sinkro

ENSEMBLE SINKRO Ensemble Sinkro General Álava 24,4-Ezk 01009 Vitoria-Gasteiz [email protected] www.espaciosinkro.com Guillermo Lauzurica +34688887139 Jabi Alonso +34 619390488 [email protected] Ensemble Sinkro is a contemporary music ensemble based in Vitoria- Gasteiz, which has had its home in the ‘Jesús Guridi’ Music Conservatory since 1985, when it was founded with Juanjo Mena as its first director. Ensemble Sinkro is a group that specialises in the realm of new technologies used in modern musical creation. Its hallmarks are the exploration of new modes of expression, experimentation with new instrumental techniques, manipulation of sound via electroacoustic media, interaction with new technologies and fusion with other artistic disciplines such as dance, video or painting. Ensemble Sinkro's main objective is to promote and disseminate newly created contemporary music works. To this end, we commission works from the most prominent present-day composers for their exclusive premieres at concerts. It has been the resident group at the Bernaola Festival in Vitoria- Gasteiz since 2005, where it presents its most innovative projects, focusing on the integration of sound and image and the acoustic and scenic space, offering a mixture of instrumental works, electroacoustics, improvisation, dance, plastic arts, video and theatre. It also tackles different fields of musical experimentation at cultural venues through exchanges with artists and institutions and by collaborating with internationally renowned soloists and ensembles. It also -

Ortad. Y Indice

a c i s ú m e d s a r o d a e r c creado ras de úsic a www.migualdad.es/mujer creadoras de úsic a © Instituto de la Mujer (Ministerio de Igualdad) Edita: Instituto de la Mujer (Ministerio de Igualdad) Condesa de Venadito, 34 28027 Madrid www.inmujer.migualdad.es/mujer e-mail: [email protected] Idea original de cubierta: María José Fernández Riestra Diseño cubierta: Luis Hernáiz Ballesteros Diseño y maquetación: Charo Villa Imprime: Gráficas Monterreina, S. A. Cabo de Gata, 1-3 – 28320 Pinto (Madrid) Impreso en papel reciclado libre de cloro Nipo: 803-10-015-2 ISBN: 978-84-692-7881-9 Dep. Legal: M-51959-2009 Índice INTRODUCCIÓN 9 EDAD MEDIA: MÚSICA, AMOR, LIBERTAD 13 Blanca Aller Nalda DAMAS Y REINAS: MUSICAS EN LA CORTE. RENACIMIENTO 29 Mª Jesús Gurbindo Lambán LABERINTOS BARROCOS 41 Virginia Florentín Gimeno MÚSICA, AL SALÓN. CLASICISMO 55 María José Fernández Riestra “COMO PRUEBA DE MI TALENTO”. COMPOSITORAS DEL SIGLO XIX 69 María Jesús Fernández Sinde TIEMPOS DE VANGUARDIA, AIRES DE LIBERTAD. LAS COMPOSITORAS DE LA PRIMERA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX 89 Gemma Solache Vilela COMPONIENDO EL PRESENTE. SONIDOS FEMENINOS SIN FRONTERAS 107 Ana Alfonsel Gómez Bibliografía y Discografía 125 Libreto 151 7 Introducción En el curso académico 2006-2007, siete profesoras de Música de Educación Secun- daria llevaron a cabo un proyecto que, tanto por su planteamiento pedagógico y didáctico como por su rigor, belleza e interés, llamó la atención del Instituto de la Mujer. Algunas de estas profesoras, que habían coincidido en un Tribunal de Oposiciones al Cuerpo de Profesorado de Enseñanza Secundaria por la especialidad de música, for - maron un Grupo de Trabajo para que el alumnado investigara la composición musi - cal también como obra femenina. -

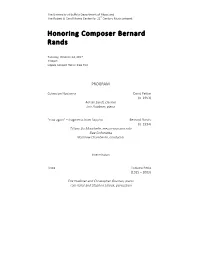

PRINTABLE PROGRAM Bernard Rands

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Honoring Composer Bernard Rands Tuesday, October 24, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Coleccion Nocturna David Felder (b. 1953) Adrián Sandí, clarinet Eric Huebner, piano "now again" – fragments from Sappho Bernard Rands (b. 1934) Tiffany Du Mouchelle, mezzo-soprano solo Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Intermission Linea Luciano Berio (1925 – 2003) Eric Huebner and Christopher Guzman, piano Tom Kolor and Stephen Solook, percussion Folk Songs Bernard Rands I. Missus Murphy’s Chowder II. The Water is Wide III. Mi Hamaca IV. Dafydd Y Garreg Wen V. On Ilkley Moor Baht ‘At VI. I Died for Love VII. Über d’ Alma VIII. Ar Hyd y Nos IX. La Vera Sorrentina Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Emlyn Johnson, flute Erin Lensing, oboe Adrián Sandí, clarinet Michael Tumiel, clarinet Jon Nelson, trumpet Kristen Theriault, harp Eric Huebner, piano Chris Guzman, piano Tom Kolor, percussion Steve Solook, percussion Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano (solo) Julia Cordani, soprano Minxin She, alto Hanna Hurwitz, violin Victor Lowrie, viola Katie Weissman, ‘cello About Bernard Rands Through a catalog of more than a hundred published works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure in contemporary music. His work Canti del Sole, premiered by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta, and the New York Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral suites Le Tambourin, won the 1986 Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. His work Canti d'Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy award in 2000. -

Costa Rica PR Country Landscape 2011

Costa Rica PR Country Landscape 2011 Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management ● ● ● ● Acknowledgements Produced by: Lauren E. Bonello, senior public relations student at the Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications, and master’s of science in Management student at the Hough Graduate School of Business, University of Florida (UF); Vanessa Bravo, doctoral candidate at the UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications, and Fulbright master’s of arts in Mass Communications, University of Florida; and Monica Morales, Fulbright master’s student at the UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications. Supervised and guided by: Juan-Carlos Molleda, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator, UF Department of Public Relations, College of Journalism and Communications and Coordinator of the GA Landscape Project. Read and approved by: John Paluszek, Senior Counsel of Ketchum and 2010-2012 Chair of the Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management. Revised & signed off by: Carmen Mayela Fallas, president of Comunicación Corporativa Ketchum. Date of completion: April 2011. Public Relations Industry Brief History Latin American Origins Latin American studies about the origins of public relations in the continent establish a common denominator as to the source of the practice in the region. Costa Rica is no exception, and this common denominator plays a relatively important goal in the development and establishment not only in the country, but also for Central America in particular. According to early registries, the genesis of public relations in Latin America is closely related to the introduction of foreign companies, which were used to having public relations as part of their businesses, into the local economies (Molleda & Moreno, 2008). -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 Online, Summer 2015

Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Summer 2015: Volume 31, Online Issue p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 In Memoriam Joseph de Pasquale Remembered p. 11 Recalling the AVS Newsletter: English Viola Music Before 1937 In recalling 30 years of this journal, we provide a nod to its predecessor with a reprint of a 1976 article by Thomas Tatton, followed by a brief reflection by the author. Feature Article p. 13 Concerto for Viola Sobre un Canto Bribri by Costa Rican composer Benjamín Gutiérrez Or quídea Guandique provides a detailed look at the first viola concerto of Costa Rica, and how the country’s history influenced its creation. Departments p. 25 In the Studio: Thought Multi-Tasking (or What I Learned about Painting from Playing the Viola) Katrin Meidell discussed the influence of viola technique and pedagogy in unexpected areas of life. p. 29 With Viola in Hand: Experiencing the Viola in Hindustani Classical Music: Gisa Jähnichen, Chinthaka P. Meddegoda, and Ruwin R. Dias experiment with finding a place for the viola in place of the violin in Hindustani classical music. On the Covers: 30 Years of JAVS Covers compiled by Andrew Filmer and David Bynog Editor: Andrew Filmer The Journal of the American Viola Society is Associate Editor: David M. Bynog published in spring and fall and as an online- only issue in summer. The American Viola Departmental Editors: Society is a nonprofit organization of viola At the Grassroots: Christine Rutledge enthusiasts, including students, performers, The Eclectic Violist: David Wallace teachers, scholars, composers, makers, and Fresh Faces: Lembi Veskimets friends, who seek to encourage excellence in In the Studio: Katherine Lewis performance, pedagogy, research, composition, New Music Reviews: Andrew Braddock and lutherie. -

Costa Rican MUSIC

Costa Rican MUSIC A small peek into the culture that fills the air of Costa Rica . By Trent Cronin During my time spent in the country of Costa Rica, I found a lot of PURA VIDA different sounds that catch your ear while you are in Costa Rica. After sorting This is a picture of a guy through the honking horns and barking dogs, you’ll find two types of music. I met named Jorge; he These two types of music are the traditional Latin American music and the more works at the airport in modern, or Mainstream, music that we are familiar with in the States. The Latin Heredia. He was telling American music includes some well-known instruments like the guitar, maracas, some me that music is in his veins. This is a good type of wind instrument (sometimes an ocarina) and the occasional xylophone. The example of how every music style tends to be very up beat and gives of a happy vibe, although there are Costa Rican holds some sad songs. Sometimes, in the larger, more populated, parts of the city, you can music near and dear to find one or more street performers playing this type of music. I don’t know what it is their heart. about hearing someone sing in a foreign language, but I like it. I will admit; I was a little surprised to walk passed a car and hear Beyonce’ being played. After further time spent I found out that other famous music artist like Metallica, The Beatles, Michael Jackson, and Credence Clear Water Revival (CCR) have diffused into the radio waves of Costa Rica. -

Costa Rican Composer Benjamín Gutiérrez and His Piano Works

ANDRADE, JUAN PABLO, D.M.A. Costa Rican Composer Benjamín Gutiérrez and his Piano Works. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 158 pp. The purpose of this study is to research the life and work of Costa Rican composer Benjamín Gutiérrez (b.1937), with particular emphasis on his solo piano works. Although comprised of a small number of pieces, his piano output is an excellent representation of his musical style. Gutiérrez is regarded as one of Costa Rica’s most prominent composers, and has been the recipient of countless awards and distinctions. His works are known beyond Costa Rican borders only to a limited extent; thus one of the goals of this investigation is to make his music more readily known and accessible for those interested in studying it further. The specific works studied in this project are his Toccata y Fuga, his lengthiest work for the piano, written in 1959; then five shorter pieces written between 1981 and 1992, namely Ronda Enarmónica, Invención, Añoranza, Preludio para la Danza de la Pena Negra and Danza de la Pena Negra. The study examines Gutiérrez’s musical style in the piano works and explores several relevant issues, such as his relationship to nationalistic or indigenous sources, his individual use of musical borrowing, and his stance toward tonality/atonality. He emerges as a composer whose aesthetic roots are firmly planted in Europe, with strong influence from nineteenth-century Romantics such as Chopin and Tchaikovsky, but also the “modernists” Bartók, Prokofiev, Milhaud, and Ginastera, the last two of whom were Gutiérrez’s teachers. The research is divided into six chapters, comprising an introduction, an overview of the development of art music in Costa Rica, a biography of Gutiérrez, a brief account of piano music in the country before Gutiérrez and up to the present day, a detailed study of his solo piano compositions, and conclusions. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE the 1964 Festival Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The 1964 Festival of Music of the Americas and Spain: A Critical Examination of Ibero- American Musical Relations in the Context of Cold War Politics A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Alyson Marie Payne September 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Chairperson Dr. Walter Clark Dr. Rogerio Budasz Copyright by Alyson Marie Payne 2012 The Dissertation of Alyson Marie Payne is approved: ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the tremendous help of my dissertation committee, Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Dr. Walter Clark, and Dr. Rogerio Budasz. I am also grateful for those that took time to share their first-hand knowledge with me, such as Aurelio de la Vega, Juan Orrego Salas, Pozzi Escot, and Manuel Halffter. I could not have completed this project with the support of my friends and colleagues, especially Dr. Jacky Avila. I am thankful to my husband, Daniel McDonough, who always lent a ready ear. Lastly, I am thankful to my parents, Richard and Phyllis Payne for their unwavering belief in me. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The 1964 Festival of Music of the Americas and Spain: A Critical Examination of Ibero- American Musical Relations in the Context of Cold War Politics by Alyson Marie Payne Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Music University of California, Riverside, September 2012 Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Chairperson In 1964, the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Institute for Hispanic Culture (ICH) sponsored a lavish music festival in Madrid that showcased the latest avant-garde compositions from the United States, Latin America, and Spain.