Strengthening Maritime Cooperation in East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

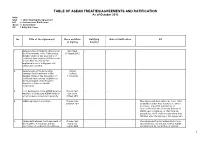

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21 -

An Evolving ASEAN: Vision and Reality

Menon • Lee An Evolving ASEAN Vision and Reality The formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in was originally driven by political and security concerns In the decades that followed ASEAN’s scope evolved to include an ambitious and progressive economic agenda In December the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was formally launched Although AEC has enjoyed some notable successes the vision of economic integration has yet to be fully realized This publication reviews the evolution of ASEAN economic integration and assesses the major achievements It also examines the challenges that emerged during the past decade and provides recommendations on how to overcome them About the Asian Development Bank AN EVOLVING ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous inclusive resilient and sustainable Asia and the Pacifi c while sustaining its e orts to eradicate extreme poverty Established in it is owned by members— from the region Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue loans equity investments guarantees grants and technical assistance ASEAN: AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY VISION Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBER AND REALITY ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org 9 789292 616946 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBEr 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 12-1995 Basic Documents - Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Sucharitkul, Sompong, "Basic Documents - Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note" (1995). Publications. Paper 540. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs/540 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \ I BASIC DOCUMENTS lfiE'TH ASEAN SUMMIT BANGKOK, DECEMBER 14- 15, 1995 BANGKOK SUMMIT DECLARATION AND ANNEXES* [Done at Bangkok, December 15, 1995] + Cite as 35 ILM ..... (1996) + TREATY ON THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA NUCLEAR WEAPON-FREE ZONE .. WITH ANNEX AND PROTOCOL** [Done at Bangkok, December 15, 1995] + Cite as 35 ILM ..... (1996) + INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL * Reproduced from the text supplied by the ASEAN Secretariat. The Introductory Note was prepared for International Legal Materials by Sompong Sucharitkul, O.C.L., Distinguished Professor of International and Comparative Law, Golden Gate University School of Law, First ASEAN Secretary-General (Thailand) 1967-1970. ** Reproduced from the text supplied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, with an Introductory Note by Sompong Sucharitkul. 1 ASEAN, The Association of South-East Asian Nations was established by the ASEAN Declaration of August 8, 1967 in Bangkok. -

ASEAN and the Environment Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 1993 ASEAN and the Environment Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation 3 Asian Yearbook of Int'l. L. (1993) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Asian Yearbook of International Law published under the auspices of the Foundation for the Development of International Law in Asia (DILA) General Editors Ko Swan Sik- M.C.W. Pinto - J.J.C. Syatauw VOLUME 3 1993 ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONMENT By SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONlVIENT by SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONMENT I. ASEAN AWARENESS OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT This is part of a series of studies devoted to the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a dynamic regional organization for social, cultural and economic cooperation. 1 The ASEAN Society currently comprises six regional members : Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and since January 7, 1984, Brunei Darussalam. 2 ASEAN tends to grow in membership and closer association with regional neighbors 3 and to expand in further intensified cooperation with its non-ASEAN, non-regional partners. 4 The object of this study is to examine some of ASEAN collective endeavors in the implementation of environmental protection within the ASEAN region and beyond. -

ASEAN Charter

CHARTER OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING with satisfaction the significant achievements and expansion of ASEAN since its establishment in Bangkok through the promulgation of The ASEAN Declaration; RECALLING the decisions to establish an ASEAN Charter in the Vientiane Action Programme, the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Charter and the Cebu Declaration on the Blueprint of the ASEAN Charter; MINDFUL of the existence of mutual interests and interdependence among the peoples and Member States of ASEAN which are bound by geography, common objectives and shared destiny; INSPIRED by and united under One Vision, One Identity and One Caring and Sharing Community; UNITED by a common desire and collective will to live in a region of lasting peace, security and stability, sustained economic growth, shared prosperity and social progress, and to promote our vital interests, ideals and aspirations; RESPECTING the fundamental importance of amity and cooperation, and the principles of sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity, non-interference, consensus and unity in diversity; ADHERING to -

“Working Together” for Peace and Prosperity of Southeast Asia, 1945 – 1968: the Birth of the Asean Way

“WORKING TOGETHER” FOR PEACE AND PROSPERITY OF SOUTHEAST ASIA, 1945 – 1968: THE BIRTH OF THE ASEAN WAY Kazuhisa Shimada Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of Politics School of History and Politics University of Adelaide January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv THESIS DECLARATION vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii ABBREVIATIONS viii FIGURES ix INTRODUCTION 1 The history of international relations in Southeast Asia 2 The thesis 5 The structure of the thesis 7 1 THE ASEAN WAY – HOW HAS IT BEEN IDENTIFIED? 10 The ASEAN Way 10 Scholarly discussion of the ASEAN Way 13 (i) The principle of non-interference 14 (ii) Face-saving behaviour 18 (iii) Consultations 20 (iv) Informality 22 (v) The spirit of working together 23 The influence of Southeast Asian cultures on the ASEAN Way 24 ASEAN and its precursors: The origin of the ASEAN Way 26 Concluding remarks 29 2 AN AWAKENING OF REGIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS 31 Southeast Asia after the Japanese surrender 31 The advent of the Cold War 32 Towards self-reliance 41 The birth of regional consciousness 47 ii The political situation in Indonesia 49 The development of the plan 54 The significance of the establishment of the ASA 56 Concluding remarks 59 3 THE ATTEMPT TO FIND A REGIONAL SOLUTION TO A REGIONAL PROBLEM 60 The declaration of the Malaysia plan 60 The regional situation in a broader context 66 The reaction from potential claimants 67 Starting the verbal war 75 Seeking peaceful coexistence 83 The beginning of discord 97 The significance of the Manila agreements and Maphilindo 107 -

Asean-Un Post-Nargis Partnership Charting a New Course a New Course Asean-Un Post-Nargis Partnership

CHARTING ASEAN-UN POST-NARGIS PARTNERSHIP POST-NARGIS ASEAN-UN A NEW COURSE CHARTING A NEW COURSE ASEAN-UN POST-NARGIS PARTNERSHIP ISBN 978-602-8411-41-7 CHARTING A NEW COURSE ASEAN-UN Post-Nargis Partnership asean asean The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia For inquiries, contact: Public Outreach and Civil Society Division The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 Email : [email protected] Writer Lisa Nicol-Woods General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN website: www.asean.org Contributing Writer Catalogue-in-Publication Data Adelina Kamal Charting a New Course: ASEAN-UN Post-Nargis Partnership Chief Editor Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, August 2010 Alanna Jorde 363.34595 Graphic Designers 1. ASEAN – Disaster Management Partnership Bobby Haryanto 2. Social Action – Disaster Relief Yulian Ardhi ISBN 978-602-8411-41-7 Publication Assistants Juliet Shwegaung Sandi Myat Aung The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper Sithu Koko acknowledgement. Zaw Zaw Aung Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2010 Cover photo All rights reserved ASEAN HTF Collection Acknowledgements he ASEAN Humanitarian Task Force for Victims of Cyclone Nargis T(AHTF) expresses its deep gratitude and sincere appreciation to all those who collaborated with us in the coordinated effort to alleviate the suffering of survivors of Cyclone Nargis. -

Asean, a Fragmented Integration in a Changing World

Fédéralisme 2034-6298 Volume 11 : 2011 Numéro 2 - Le régionalisme international : regards croisés. Europe, Asie et Maghreb, 1082 Asean, a fragmented integration in a changing world Olivier Dupont Olivier Dupont : Research fellow, University of liège Abstract : This paper looks at the way the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) operates, in terms of the participation of its member states. Since its inception in 1967, Asean has apparently been driven by realism. But other mechanisms have gradually come into play and some group dynamics have emerged over time through the summits and treaties. Several aspects of this process should be highlighted: • the achievement of independence among countries in the area and the consolidation of this independence; • a willingness to resist the rise of communism in the region; • the easing of tension and the stabilising role in the region played by the Association; • the common desire to promote growth and the efforts to create a sense of identity; • the growing role played by the Association and its member states in a multilateral framework and especially in relation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). 1. Consolidating independence After the Japanese surrender in September 1945, the first priority of the victorious powers with interests in Southeast Asia was to restore the authority they held there before the conflict. This was what happened in most countries that put together the framework which several years later would become Asean: the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Burma and Vietnam. However, after the Allied victory, the situation changed significantly from three viewpoints. Firstly, despite having won the war, the Western powers had become considerably weaker during the five years of conflict and the time had come for their own reconstruction.