Changing Landscapes of the Isle of Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

• COLLEGE Mflfilzine »

THE • COLLEGE MflfilZINE » PUBLISHED THREE TIMES YEflRiy THE BARROVIAN. No. 203 FEBRUARY 1948 CONTENTS Page Page Editorial 397 Holland 419 Random Notes 398 Impressions of Spain and Masters 399 the Basque Country ... 420 School Officers 400 Germany and the Germans 423 Salvete 400 Jamboree 424 Valete 401 General Knowledge Paper 42.5 Founders' Day 401 The Societies 431 Honours List 403 Aero Modellers' Club ... 436 Prize List 404 Cambridge Letters 436 O. K. W. News 406 House Notes 437 Obituary 407 J.T.C. Notes 441 Roll of Service 409 Scouting 442 King William's College Swimming 443 Society 409 Shooting 443 King William's College Rugby Football 443 Lodge 410 The " Knowles " Cup ... 444 The Concert 410 Chapel Window Fund ... 452 St. Joan 412 K.W.C. War Memorial Mr. Broadhead 415 Fund 453 Chapel Notes 415 O.K.W. Sevens Fund ... 457 The Library 417 Contemporaries 457 France 418 EDITORIAL. The School Magazine can do its work by two methods. The firsc is the chronicling of the bare facts of school life, the lists of the terms functions and functionaries, and the Sports events. The second is the interpretation of the spirit of the school and of its multifarious activities by means of descriptive writing. Often the two methods are mixed; for instance, the report on the play will contain both the programme and a criticism of the production or, an account of a Rugger match will include the names of the team and the scorers, and a description of how the team played. The facts are the bones of the Harrovian, but without the flesh and blood of ideas it cannot be made to live. -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

Corkish Spouses

Family History, Volume IV Corkish - Spouse 10 - 1 Corkish Spouses Margery Bell married Henry Corkish on the 18th of August, 1771, at Rushen. Continued from 1.8.6 and see 10.2.1 below. Catherine Harrison was the second wife of Christopher Corkish when they married on the 31st of October, 1837, at Rushen. Continued from 10.4.1 and see 10.3 below. Isabella Simpson was the second wife of William Corkish, 4th September, 1841, at Santan. Continued from 1.9.8 and see 10.29.7 below. Margaret Crennell married John James Corkish on the 20th of December, 1853, at Bride. Continued from 5.3.1.1 and see 10.20.2 below. Margaret Gelling married Isaac Corkish on the 30th of April, 1859, at Patrick. Continued from 7.2.1 and see 10.18.7 below. Margaret Ann Taylor married Thomas Corkish on the 14th of August, 1892, at Maughold. Continued from 4.13.9 and see 10.52.110.49.1 below. Margaret Ann Crellin married William Henry Corkish on the 27th of January, 1897, at Braddan. Continued from 9.8.1 and see 10.5 below. Aaron Kennaugh married Edith Corkish on the 26th of May, 1898, at Patrick Isabella Margaret Kewley married John Henry Corkish on the 11th of June, 1898, at Bride. 10.1 John Bell—1725 continued from 1.8.6 10.1.1 John Bell (2077) ws born ca 1725. He married Bahee Bridson on the 2nd of December, 1746, at Malew. See 10.2 for details of his descendants. 10.1.2 Bahee Bridson (2078) was born ca 1725. -

The Gawne Family

Family History, Volume IV Gawne 16-1 The Gawne Family John Gawne married Elizabeth Corkish on the 31st of January, 1858, at Bride. Continued from 5.3.3 and see 16.5.1 below. John Gawne married Esther McKneale on the 15th of October, 1839, at Malew. Their grand–son Thomas Kinrade married Alice Christian on the 22nd of May, 1897, at Malew. 16.1 Philip Gawne—1700 16.1.1 Philip Gawne (3287) was born circa 1700. He married Catherine Garrett circa 1720. See 16.2 for details of his descendants. 16.1.1.1 Catherine Garret (3306) was born circa 1700. She married Philip Gawne circa 1720. See 16.2 for details of her descendants. 16.2 The Children of Philip Gawne & Catherine Garrett continued from 16.1.1 and 16.1.1.1 Number & Name Type & Birthdate Place/Notes 3289 Philip B 24th Feb 1724 Bride 16.2.1 Philip Gawne (3289) was baptized on the 24th of February, 1724, at Bride. He married Joney Sayle on the 12th of October, 1751, at Lezayre. See 16.3 for details of his descendants. 16.2.1.1 Joney Sayle (3288) was born circa 1724, the daughter of John Sayle & Mary Kewley. There appears to have been two couples with these names living in Andreas around this time with approximately 15 children between them. So far no effort has been made to separate the two families. See 16.3 for details of her descendants. Printed:Sunday, 10th February, 2008 © Brian Lawson 1999, 2005 16-2 Gawne Family History, Volume IV 16.3 The Children of Philip Gawne & Joney Sayle continued from 16.2.1 and 16.2.1.1. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 17th September 2019 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 136, No. 19 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2019 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 PAGE LEFT DELIBERATELY BLANK ________________________________________________________________________ 2092 T136 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 Business transacted Questions for Written Answer .......................................................................................... 2097 1. Zero Hours Contract Committee recommendations – CoMin approval; progress; laying update report ........................................................................................................... 2097 2. GDPR breaches – Complaints and appeals made and upheld ........................................ 2098 3. No-deal Brexit – Updating guide for residents before 31st October 2019 ..................... 2098 4. No-deal Brexit – Food supply contingency plans; publishing CoMin paper.................... 2098 5. Tax returns – Number submitted April, May and June 2018; details of refunds ............ 2099 6. Common Purse Agreement – Consideration of abrogation ........................................... -

IOMFHS Members' Interests Index 2017-2020

IOMFHS Members’ Interests Index 2017-2021 Updated: 9 Sep 2021 Please see the relevant journal edition for more details in each case. Surnames Dates Locations Member Journal Allen 1903 08/9643 2021.Feb Armstrong 1879-1936 Foxdale,Douglas 05/4043 2018.Nov Bailey 1814-1852 Braddan 08/9158 2017.Nov Ball 1881-1947 Maughold 02/1403 2021.Feb Banks 1761-1846 Braddan 08/9615 2020.May Barker 1825-1897 IOM & USA 09/8478 2017.May Barton 1844-1883 Lancs, Peel 08/8561 2018.May Bayle 1920-2001 Douglas 06/6236 2019.Nov Bayley 1861-2007 08/9632 2020.Aug Beal 09/8476 2017.May Beck ~1862-1919 Braddan,Douglas 09/8577 2018.Nov Beniston Leicestershire 08/9582 2019.Aug Beniston c.1856- Leicestershire 08/9582 2020.May Blanchard 1867 Liverpool 08/8567 2018.Aug Blanchard 1901-1976 08/9632 2020.Aug Boddagh 08/9647 2021.Jun Bonnyman ~1763-1825 02/1389 2018.Aug Bowling ~1888 Douglas 08/9638 2020.Nov Boyd 08/9647 2021.Jun Boyd ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Boyd(Mc) 1788 Malew 02/1385 2018.Feb Boyde ~1821 IOM 09/8549 2021.Jun Bradley -1885 Douglas 09/8228 2020.May Breakwell -1763 06/5616 2020.Aug Brew c.1800 Lonan 09/8491 2018.May Brew Lezayre 06/6187 2018.May Brew ~1811 08/9566 2019.May Brew 08/9662 2021.Jun Bridson 1803-1884 Ramsey 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson 1783 Douglas 08/9547 2018.Feb Bridson c.1618 Ballakew 08/9555 2018.May Bridson 1881 Malew 08/8569 2018.Nov Bridson 1892-1989 Braddan,Massachusetts 09/8496 2018.Nov Bridson 1861 on Castletown, Douglas 08/8574 2018.Nov Bridson ~1787-1812 Braddan 09/8521 2019.Nov Bridson 1884 Malew 06/6255 2020.Feb Bridson 1523- 08/9626 -

The Isle of Man Strategic Plan 2016

Town and Country Planning Act 1999 The Island Development Plan THE ISLE OF MAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 Towards a Sustainable Island The Cabinet Office th Adopted by Order on: 16 February 2016 Approved by Tynwald on: 15th March 2016 Coming into operation on: 1st April 2016 Statutory Document No. 2016/0060 Price: £4 TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1999 THE ISLE OF MAN STRATEGIC PLAN This document comprises that referred to in article 2 of the Town and Country Planning (Isle of Man Strategic Plan) Order 2016, and is, accordingly, annexed to that Order. CONTENTS Foreword Preface Chapter Title Page 1 Introduction 5 2 Strategic Aim 8 3 Strategic Objectives 11 4 Strategic Policies 13 5 Island Spatial Strategy 20 6 General Development Considerations 31 7 The Environment 36 8 Housing 60 9 Business and Tourism 77 10 Sport, Recreation, Open Space and Community Facilities 88 11 Transport, Infrastructure and Utilities 96 12 Minerals, Energy and Waste 108 13 Implementation, Monitoring and Review 115 Appendices 116 1 Definitions and Glossary of Terms 117 2 Relationship between Strategic Objectives and Strategic Policies 122 3 Settlement Pattern 126 4 Guidance on Requirements for the Undertaking of a Flood Risk Assessment 128 5 Environmental Impact Assessment 130 6 Open Space Requirements for New Residential Development 132 7 Parking Standards 137 8 Existing and Approved Dwellings by Local Authority Area 140 9 Employment Land Availability 141 Diagrams 1 Spatial Framework Key Diagram 29 1 Foreword 2007 I am pleased to be associated with the publication of the Island’s first Strategic Plan, and would like to take this opportunity to thank all of those individuals, special-interest groups, businesses, Local Authorities, and Government bodies who have contributed to the final form of this long-awaited document. -

The Archaeology of Manx Church Interiors: Contents and Contexts 1634-1925

The Archaeology of Manx Church Interiors: contents and contexts 1634-1925 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Patricia Truce McClure May 2013 © Patricia Truce McClure, 2013. All rights reserved ii The Archaeology of Manx Church Interiors: contents and contexts 1634-1925 by Patricia Truce McClure Abstract Despite the large amount of historical church archaeology carried out within English churches, the relevance of British regional variations to conclusions reached has only been recognized relatively recently (Rodwell 1996: 202 and Yates 2006: xxi). This offered opportunities to consider possible meanings for the evolving post- Reformation furnishing arrangements within Manx churches. The resultant thesis detailed the processes involved whilst examining changes made to the Anglican liturgical arrangements inside a number of Manx and Welsh churches and chapels- of-ease between 1634 and 1925 from previously tried and tested structuration, and sometimes biographical, perspectives for evidence of changes in human and material activity in order to place Manx communities within larger British political, religious and social contexts. Findings challenged conclusions reached by earlier scholarship about the Commonwealth period in Man. Contemporary modifications to material culture inside Manx churches implied that Manx clergymen and their congregations accepted the transfer of key agency from ecclesiastical authorities to Parliamentary actors. Thus Manx religious practices appeared to have correlated more closely, albeit less traumatically, with those in England and Wales during the same period than previously recognized, although the small size of this study could not discover the geographical extent of disarray within Island parishes. -

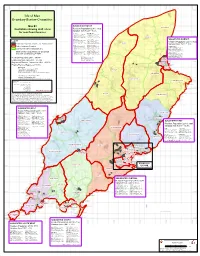

Isle of Man Boundary Review Committee

Isle of Man Boundary Review Committee SUGGESTED NORTH Map B1 BRIDE PARISH Illustration showing draft ideas Resident Population (2011): 7652 Variation from 7,041 = 8.5% for new Constituencies ANDREAS EAST LEZAYRE Resident Population (2011): 1426 Resident Population (2011): 445 Eligible Electors (2011): 1143 Eligible Electors (2011): 366 Registered Electors (2011): 1120 Registered Electors (2011): 351 Eligible Electors Registered: 98% Eligible Electors Registered: 95.9% ANDREAS BALLAUGH WEST LEZAYRE SUGGESTED RAMSEY Resident Population (2011): 1042 Resident Population (2011): 835 Legend Eligible Electors (2011): 865 Eligible Electors (2011): 667 Registered Electors (2011): 829 Registered Electors (2011): 636 Resident Population (2011): 7820 Proposed Development Areas (source: DOI, Planning Division) Eligible Electors Registered: 95.8% Eligible Electors Registered: 95.4% JURBY BRIDE NORTH MAUGHOLD Variation from 7,041 = 11% Existing Constituency Boundaries Resident Population (2011): 401 Resident Population (2011): 606 Eligible Electors (2011): 331 Eligible Electors (2011): 491 RAMSEY NORTH Registered Electors (2011): 316 Registered Electors (2011): 469 Resident Population (2011): 4251 Suggested Polling Districts DECEMBER 2012 Eligible Electors Registered: 95.5% Eligible Electors Registered: 95.5% Eligible Electors (2011): 3446 Registered Electors (2011): 3112 JURBY SOUTH MAUGH OLD Eligible Electors Registered: 90.3% Ideal resident population per proposed Resident Population (2011): 797 Resident Population (2011): 371 Eligible Electors (2011): -

The Harrovian

THE HARROVIAN KING WILLIAM'S COLLEGE M AG AZI N E Published three times yearly N U M B K R 227 . DECEMBER I 9 O.K.W. DINNERS, Etc. Liverpool Society : On Friday, December i6th, 1955. Details from G. F. Harnden, 35 Victoria Street, Liverpool I. Harrovian Society : On Tuesday, December 27th, 1955. Annual Dance at the Castle Mona Hotel, Douglas. Details from G. P. Alder, Struan, Quarterbridge Road, Douglas. Manchester Society : On Friday, January I3th, 1956. Annual Dinner at the Old Rectory Club, Deansgate, Manchester. Details from G. Aplin, c/o E.I.A., Liner's House, St. Ann's Square, Manchester 2. London Society . On Friday, February loth, 1956. Annual Dinner on the eve of the England-Ireland game at Twickenham. Details from C. J. W. Bell, n Netherton Grove, St. Margarets, Middlesex. Harrovian Society : On Tuesday, March I3th, 1956. Annual Dinner at the Castle Mona Hotel, Douglas. Details from G. P. Alder, Stru.in, Quarterbridge Road, Douglas. Advance Notice : Harrovian Day at K.W.C. will take place on Thursday, May 3ist, 1956. Further details will be given in the next issue. THE BARROVIAN 227 DECEMBER 1955 CONTENTS Page Random Notes School Officers Valete Salvete Chapel Notes Library Notes Correspondence Founder's Day Honours List University Admissions College Concert End of Term Revue The Musick Makers Miss Phyllis Bentley World Jamboree Wolfit in Arden The Houses ... The Literary and Debating Society Gramophone Society Manx Society The Knights Dramatic Society Photographic Society Scientific Society Jazz Club Chess Club Shooting The Badminton Society Golfing Society Cricket Swimming Rugby Football Combined Cadet Force ist K.W.C. -

Isle of Man Family History Society * * * INDEX * * * IOMFHS JOURNALS

Isle of Man Family History Society AN M F O y t E e L i c S I o S y r to is H Family * * * INDEX * * * IOMFHS JOURNALS Volumes 29 - 38 January 2007 - November 2016 The Index is in four sections Indexed by Names - pages 1 to 14 Places - pages 15 to 22 Photographs - pages 23 to 44 Topics - pages 45 to 78 Compiled by Susan J Muir Registered Charity No. 680 IOM FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNALS INDEX FEBRUARY 2007 to NOVEMBER 2016 1. NAMES FAMILY NAME & FIRST NAME(S) PLACE YEAR No. PAGE Acheson Walter Douglas 2014 1 16 Allen Robert Elliott Bellevue 2015 1 15 Anderson Wilfred Castletown 2014 1 16 Annim William Jurby 2015 2 82 Ansdel Joan Ballaugh 2010 4 174 Atkinson Jonathan Santon 2012 4 160 Banks (Kermode) William Peel 2009 1 43 Bannan William Onchan 2014 2 64 Bannister Molly Sulby 2009 2 87 Bates William Henry Douglas 2014 1 16 Baume Pierre Jean H. J. Douglas 2008 2 80 Beard Ann Isle of Man 2012 1 40 Bell Ann Castletown 2012 1 36 Bell Frank Douglas 2007 3 119 Birch Emily Rushen 2016 2 74 Bishop Edward Kirk Michael 2013 2 61 Black Harry Douglas 2014 1 16 Black James IoM 2015 2 56 Black Stanley Douglas 2014 1 16 Blackburn Benny Douglas 2008 1 19 Boyde Eliza Ballaugh 2010 3 143 Boyde Simon Malew 2013 3 136 Bradford James W. Ramsey 2014 1 16 Bradshaw Clara Jane Ballaugh 2014 1 15 Braid Thomas IoM 2015 2 56 Braide William Braddan 2014 1 32 Breary William Arthur Douglas 2009 4 174 Brew Caesar Rushen 2014 3 108 Brew John Manx Church Magazine 1899 2007 3 123 Brew John Douglas 2012 1 5 Brew Robert Santan 2016 3 139 Brice James Douglas 2014 3 123 Brideson -

The Harrovian

THE HARROVIAN KING WILLIAM'S COLLEGE MAGAZINE Published three times yearly NUMBER 231 . MARCH THE BARROVIAN 231 MARCH 1957 CONTENTS Page In Memoriam: W.K.S 58 Random Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 61 School Officers ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 61 Valete 62 Salvete 63 Library Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 63 Chapel Notes ... ... ... ...... ... ... 63 Two Concerts ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 64 College Concert ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 65 Second House Plays ... ... ... ... ... ... 67 Mr. Gladstone at K.W.C 69 Literary and Debating Society ... ... ... ... ... 70 Manx Society ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 71 Music Club ... ... ... .,, ... ... ... ... 72 Gramophone Society ... ... ... ... ... ... 73 The Knights 73 Photographic Society ... ... ... ... ... ... 74 Scientific Society ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 74 Chess Club 75 Shooting Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 75 The Houses 76 Rugby Football 78 O.K.W. Section 86 Obituaries ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 94 G.K.P. 95 Contemporaries ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 100 53 THEBARROVIAN [March IN MEMORIAM WILLIAM KENDALL SMEETON The beginning of term was saddened by the news of Mr. Smeeton's death just before Christmas. On the second Sunday of term a memorial service was held in chapel, during which the Principal gave an address, which we print below. It is followed by some memories of Mr. Smeeton which the Vice Principal has written. With these tributes we send our deep sympathy to Mrs. Smeeton, Susan and Barry. The Principal's Address William Kendall Smeeton died a few days before Christmas, and had he lived another day he would have been 54 years old. Of these years more than 29 were spent at College. He was educated at Wellington and Pembroke College, Oxford. At Wellington he was head of dormitory (conesponding to house at College) and captain of its Rugby XV, and at Oxford he played rugger for his College and gained an honours degree in Classics.