Read Ben Moffett's Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: the (Engadin Ski Marathon)

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2017, Article ID 9821757, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9821757 Research Article The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: The (Engadin Ski Marathon) Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis,1,2 Jan Heller,3 and Beat Knechtle4,5 1 Exercise Physiology Laboratory, Nikaia, Greece 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Metropolitan College, Athens, Greece 3Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 4Gesundheitszentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland 5Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence should be addressed to Beat Knechtle; [email protected] Received 20 April 2017; Accepted 17 July 2017; Published 21 August 2017 Academic Editor: Laura Guidetti Copyright © 2017 Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. It is well known that athletes from a specific region or country are dominating certain sports disciplines such as marathon running or Ironman triathlon; however, little relevant information exists on cross-country skiing. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the aspect of region and nationality in one of the largest cross-country skiing marathons in Europe, the “Engadin Ski Marathon.” All athletes ( = 197,125) who finished the “Engadin Ski Marathon” between 1998 and 2016 were considered. More than two-thirds of the finishers (72.5% in women and 69.6% in men) were Swiss skiers, followed by German, Italian, and French athletes in both sexes. Most of the Swiss finishers were from Canton of Zurich (20.5%), Grisons (19.2%), and Berne (10.3%). -

Cross Country Marathon Calender 2018 / 2019 Date Race Location Country Distance Additionals Serie Homepage

Cross Country Marathon Calender 2018 / 2019 date race location country distance additionals serie homepage Sa. 24.11.18 Kiilopäähiihto Saariselkä / Kiilopää FIN 50 / 20 CL www.suomenlatu.fi/tapahtumia/kiilopaahiihto/uutiset.html Sa. 01.12.18 Sgambeda Livigno ITA 30 FT www.lasgambeda.it So. 16.12.18 Kannelberglauf Hermsdorf D 20 CL www.sportverein-hermsdorf.de Sa. 29.12.18 Rymmarloppet Arvidsjaur SWE 40 CL www.skidor.com Mo. 31.12.18 Silvesterlanglauf Kössen AUT 22 FT www.nordic-center.com So. 30.12.18 Risouxloppet St. Lupicin / Jura FRA 25 / 10 FT www.skiclub-saintlupicin.jimdo.com Fr. 04.01.18 China Vasalauf Changchun CHN 50 / 25 CL 1 www.vasaloppetchina.com Fr. 04.01.19 Bedrichovska Night LM Bedrichov / Liberec CZE 30 / 17 FT www.ski-tour.cz Sa. 05.01.19 Bedrichovska Night LM Bedrichov / Liberec CZE 30 / 17 CL www.ski-tour.cz Sa. 05.01.19 Budorrennet Loten NOR 46 CL www.kondis.no Sa. 05.01.19 Nordic Ski Marathon Bruksvallarna SWE 42 / 21 CL www.skidor.com So. 06.01.19 Attraverso Campra Olivione CH 21 FT 10 www.swissloppet.com So. 06.01.19 Base Tuono Marathon Passo Coe / Folgaria ITA 30 FT www.gronlait.it So. 06.01.19 La Ronde des Cimes Les Fourgs / Jura FRA 30 / 10 FT www.marathonskitour.fr So. 06.01.19 Alpe D'Huez Marathon Alpe D'Huez Oisans FRA 30 FT www.ffs.fr So. 06.01.19 AXA Skimarathon Sagmyra SWE 42 / 21 CL www.skidor.com Fr./So. 11.-13.1.19 Tour de Ramsau Ramsau / Dachstein AUT Sa. -

The Effect of Sex and Performance Level on Pacing in Cross-Country Skiers: Vasaloppet 2004‐2017

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 The effect of sex and performance level on pacing in cross-country skiers: Vasaloppet 2004‐2017 Nikolaidis, Pantelis Theodoros ; Villiger, Elias ; Knechtle, Beat Abstract: Background Pacing, defined as percentage changes of speed between successive splits, hasbeen extensively studied in running and cycling endurance sports; however, less information about the trends in change of speed during cross-country (XC) ski racing is available. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the effect of performance (quartiles of race time (Q), with Q1 the fastest andQ4 the slowest) level on pacing in the Vasaloppet ski race, the largest XC skiing race in the world. Methods For this purpose, we analyzed female (n = 19,465) and male (n = 164,454) finishers in the Vasaloppet ski race from 2004 to 2017 using a 1-way (2 gender) analysis of variance with repeated measures to examine percentage changes of speed between 2 successive splits. Overall, the race consisted of 8 splits. Results The race speed of Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 was 13.6 ± 1.8, 10.6 ± 0.5, 9.2 ± 0.3, and 8.1 ± 0.4km/h, respectively, among females and 16.7 ± 1.7, 13.1 ± 0.7, 10.9 ± 0.6, and 8.9 ± 0.7km/h, respectively, among males. The overall pacing strategy of finishers was variable. A small sex × split interaction on speed was observed (2 = 0.016, p < 0.001), with speed difference between sexes ranging from 14.9% (Split 7) to 27.0% (Split 1) and larger changes in speed between 2 successive splits being shown for females (p < 0.001, 2 = 0.004). -

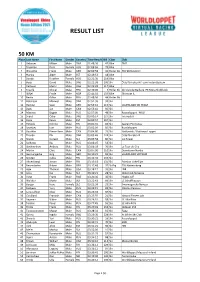

Home Edition 2021 Result List.Xlsx

RESULT LIST 50 KM Place Last Name First Name Gender Country Time Result BIB Class Club 1 Gebauer Mikael Male SWE 01:48:36 47 Bike TMT 2 Trueman Doris Female AUS 02:08:04 79 Bike 3 Wünsche Frank Male GER 02:09:58 41 Roller Ski TSV 90 Neukirch 4 Närska Alger Male EST 02:19:53 18 Bike 5 Bundy Heather Female AUS 02:22:30 119 Bike 6 Boija David Male SWE 02:22:38 100 Ski Österfärnebo IF/Team InstantSystem 7 Carlsson Martin Male SWE 02:23:28 117 Bike 8 Traullé Olivier Male FRA 02:40:00 9 Roller Ski Ski Club de Beille & IFK Mora Skidklubb 9 Stifjell Frode Male NOR 02:44:02 103 Bike Skorovas IL 10 Bertin Gilles Male FRA 02:48:56 44 Roller Ski 11 Robinson Maxwell Male SWE 02:51:36 39 Ski 12 Herling Sven Male GER 02:53:16 115 Ski SAUERLAND SKI TEAM 13 Basta Jan Male CAN 02:53:44 92 Ski 14 Маслов Вадим Male RUS 02:57:00 48 Ski Russialoppet - MSU 15 Svärd Oskar Male SWE 03:00:14 127 Ski Tvärreds IF 16 Kiple Kaivo Male EST 03:00:57 107 Ski 17 Pohjola Kimmo Male FIN 03:01:31 82 Ski Saaren Ponnistus 18 Savelyev Ivan Male RUS 03:02:09 85 Ski Russialoppet 19 Gauthier Pierre-Yves Male CAN 03:04:00 25 Ski Nakkertok / Gatineau Loppet 20 Thorén Pär Male SWE 03:05:46 124 Ski Österfärnebo IF 21 Slivnik Gorazd Male SLO 03:05:58 86 Ski Ice Power 22 Soldatov Ilya Male RUS 03:06:07 54 Ski 23 Ovchinnikov Andrey Male RUS 03:06:39 76 Ski Le Tour de Chiz 24 Martin Chris Male CAN 03:07:00 110 Ski Downtown Nordic 25 Gerstengarbe Jörg Male GER 03:10:21 93 Ski SAUERLAND SKITEAM 26 Sjösten Jukka Male FIN 03:12:40 135 Ski 27 Ahvenlampi Anton Male FIN 03:13:18 131 Ski Paimion -

Prediction of Performance in Vasaloppet Through Long Lasting Ski-Ergometer and Roller-Ski Tests in Cross-Country Skiers

Mygind et al. Int J Sports Exerc Med 2015, 1:4 ISSN: 2469-5718 International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine Original Article: Open Access Prediction of Performance in Vasaloppet through Long Lasting Ski- Ergometer and Rollerski Tests in Cross-Country Skiers Erik Mygind1*, Kristian Wulff1, Mads Rosenkilde Larsen2 and Jørn Wulff Helge2 1Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 2Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark *Corresponding author: Erik Mygind, Associate Professor, Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Nørre Alle 51, 2200, Copenhagen N, Denmark, Tel: +45 28 75 08 94, E-mail: [email protected] • The distance in ski-ergometer tests improved significantly Abstract from 18.0 ± 0.6 to 19.2 ± 0.7 km/h from pre to post after three The main purpose was to investigate if long lasting cross-country months training (c-c) test procedures could predict performance time in ‘Vasaloppet’ • A long lasting (120 minutes) Rollerski test was significantly and secondly the effect of a 16 weeks training period on a 90 min double poling performance test. 24 moderate trained c-c skiers associated with racing time in Vasaloppet pre (r = 0.78) and participated in the study and completed Vasaloppet. All skiers post (r = 0.82) three months training period carried out pre and post training tests in a 90 minutes ski-ergometer • The total body fat percentage was significantly reduced, while double poling test and a 120 minutes rollerski field test on a closed paved circuit. 19 skiers provided detailed training logs that could trunk and total lean body mass increased significantly (P < 0.05). -

Combi Package with the Finlandia Hiihto and the Vasaloppet

Combi package with the Finlandia Hiihto and the Vasaloppet 25.02.-08.03.2021 With Full guiding by the Team of Sandoz Concept The Worldloppet calendar for 2021 provides you with the possibility of combing two legendary races in one trip! You can sign up to do the Finlandia Hiihto in Finland and then the Vasaloppet in Sweden. The trip starts in the city of Lahti 100 km to the north of Helsinki. Even today, it is considered a paradise for sports, in particular cross-country skiing and ski jumping. Since 1926, Lahti has wel- comed seven world cross-country ski championships. It is exactly in its world famous stadium at the foot of the three legendary ski jumps that the start and the finish of the largest marathon in Finland occurs every winter. In 2021 they Nordic skiiers will compete on the 27th and 28th of Feb- ruary. The first part of the marathon course is the most difficult because the course is the same course used for the cross-country world championships. The second part of the course is flatter (but of course this term is quite subjective), before the race finishes in the stadium surrounded by the three ski jumps. You have the possibility of either a 65 km, 32 km or 20 km classic race on Saturday and a 65 km, 32 km and 20 km skating race on Sunday. More than 6,000 skiers will participate in the two courses over the two days. The trip follows to Sweden with the most popular and oldest cross-country ski course in the his- tory of classic Nordic skiing: the Vasaloppet. -

W Orldloppet Calendar

Worldloppet main races 2012/2013 - 2013/2014 2012/2013 2013/2014 race name distance techn country 25.08.12 24.08.13 KanGaroo Hoppet 42 km FT AUS 13.01.13 12.01.14 JiZersKÁ PADESATKa 50 km CT CZE 19.01.13 18.01.14 american BirKeBeiner: Open Track 51 km CT USA 19.01.13 18.01.14 american BirKeBeiner: Open Track 51 km FT USA 19.01.13 18.01.14 dolomitenlaUF: Classic Race 42 km CT AUT 20.01.13 19.01.14 dolomitenlaUF 60 km FT AUT 27.01.13 26.01.14 marcialonGa 70 km CT ITA 02.02.13 01.02.14 KÖniG lUdWiG laUF 50 km FT GER 03.02.13 01.02.14 KÖniG lUdWiG laUF 50 km CT GER 03.02.13 02.02.14 sapporo int. sKi MARATHon 50 km FT JPN 09.02.13 08.02.14 la transJUrassienne: La Transjurassienne 50 50 km CT FRA 10.02.13 09.02.14 la transJUrassienne: La Transjurassienne 54 57 km FT FRA 10.02.13 09.02.14 la transJUrassienne: La Transjurassienne 76 76 km FT FRA 10.02.13 09.02.14 TARTU MARATON: Open Track 63 km FT EST 16.02.13 15.02.14 GATINEAU loppet 51 km CT CAN 17.02.13 16.02.14 GATINEAU loppet 54 km FT CAN 17.02.13 16.02.14 TARTU MARATON 63 km CT EST 23.02.13 22.02.14 american BirKeBeiner 54 km CT USA 23.02.13 22.02.14 american BirKeBeiner 50 km FT USA 23.02.13 22.02.14 Finlandia- HiiHTO 50 km CT FIN FIS Marathon Cup 2012/2013 race 24.02.13 23.02.14 Finlandia- HiiHTO 50 km FT FIN ed: 24.02.13 23.02.14 Vasaloppet: Öppet Spår 90 km CT SWE r 25.02.13 24.02.14 Vasaloppet: Öppet Spår 90 km CT SWE 02.03.13 01.03.14 BieG PIASTOW 50 km CT POL 03.03.13 02.03.14 Vasaloppet 90 km CT SWE 10.03.13 09.03.14 enGadin sKIMARATHon 42 km FT SUI 15.03.13 14.03.14 BirKeBeinerrennet: -

Prediction of Performance in Vasaloppet Through Long Lasting Ski- Ergometer and Rollerski Tests in Cross-Country Skiers

Prediction of performance in Vasaloppet through long lasting ski- ergometer and rollerski tests in cross-country skiers Mygind, Erik; Wulff, Kristian; Jensen, Mads Rosenkilde; Helge, Jørn Wulff Published in: International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine DOI: 10.23937/2469-5718/1510025 Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Mygind, E., Wulff, K., Jensen, M. R., & Helge, J. W. (2015). Prediction of performance in Vasaloppet through long lasting ski- ergometer and rollerski tests in cross-country skiers. International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine, 1(5), [025]. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5718/1510025 Download date: 02. okt.. 2021 Mygind et al. Int J Sports Exerc Med 2015, 1:4 International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine Original Article: Open Access Prediction of Performance in Vasaloppet through Long Lasting Ski- Ergometer and Rollerski Tests in Cross-Country Skiers Erik Mygind1*, Kristian Wulff1, Mads Rosenkilde Jensen2 and Jørn Wulff Helge2 1Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Denmark 2Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark *Corresponding author: Erik Mygind, Associate Professor, Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, University of Copenhagen, Nørre Alle 51, 2200, Copenhagen N, Denmark, Tel: +45 28 75 08 94, E-mail: [email protected] • The distance in ski-ergometer tests improved significantly Abstract from 18.0 ± 0.6 to 19.2 ± 0.7 km/h from pre to post after three The main purpose was to investigate if long lasting cross-country months training (c-c) test procedures could predict performance time in ‘Vasaloppet’ • A long lasting (120 minutes) Rollerski test was significantly and secondly the effect of a 16 weeks training period on a 90 min double poling performance test. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Images of the Two Winter Sport Events Birkebeinerrennet and Vasaloppet

Master’s Thesis 2018 30 ECTS Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management Challenging, spectacular and less appealing versus flat, boring and highly attractive? A comparative analysis of the images of the two winter sport events Birkebeinerrennet and Vasaloppet Utfordrende, spektakulært og mindre tiltalende, kontra flatt, kjedelig og attraktivt? En komparativ analyse av imagene til vintersportsarrangementene Birkebeinerrennet og Vasaloppet Kristine Blekastad Sagheim Nature-based Tourism CONTENT PREFACE .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 SAMMENDRAG ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK, OBJECTIVE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ............................................ 9 2.1 SPORT TOURISM AND IMAGE ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 SPORT EVENT IMAGE ................................................................................................................................................................. -

News from Vasaloppets Veteranklubb January 2021 No

News from Vasaloppets Veteranklubb January 2021 No. 1 MINI-PROFILE Board member 819 Bosse Wallin Vasalopps veteran 819 Bosse Wallin was born in the village of Östnor in Mora. It's not surprising that he started skiing given where he came from. Östnor has trained a number of talented skiers. The first IFK Mora winner in Vasaloppet, Anders Ström came from Östnor as well as both Nils "Mora-Nisse" Karlsson (nine wins in Vasaloppet and a 50 km Olympic gold in St Moritz in 1948) and Gunnar Eriksson (relay gold in St Moritz in 1948 and world championship gold in 50 km in Lake Placid). We should also mention our first "50-racer", Vasalopps veteran number 9 Gösta Aronsson, also from Östnor and related to Bosse! Bosse says that when Gösta Aronsson finished his 50th race between Sälen and Mora, Bosse caught up with Gösta between Gopshus and Hökberg and accompanied him up to the control station in Hökberg. Bosse Wallin had prominent role models in Östnor– there is no doubt about that! Bosse himself has been a sharp Vasaloppet skier in his day! How about the time 4:53 in 1983? Bosse became a Vasaloppet veteran in 2013 and has also ridden Stafettvasan, Kortvasan and Halvvasan as well as Marcialonga, Engadin Ski marathon, Vasaloppet China, Birkebeinern and Svalbard Ski marathon and a number of other races. When Bosse returned to his childhood and youth in Östnor, he tells us that many other young people, started in Lilla Vasaloppet. Getting to and from school on skis during the winter was the rule than the exception. -

Performance and Participation in the 'Vasaloppet' Cross-Country Skiing Race During a Century

sports Article Performance and Participation in the ‘Vasaloppet’ Cross-Country Skiing Race during a Century Nastja Romancuk 1, Pantelis T. Nikolaidis 2 , Elias Villiger 1 , Hamdi Chtourou 3,4 , Thomas Rosemann 1 and Beat Knechtle 1,5,* 1 Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, Zurich 8006, Switzerland; [email protected] (N.R.); [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (T.R.) 2 Exercise Physiology Laboratory, Nikaia 18450, Greece; [email protected] 3 Activité Physique: Sport et Santé, UR18JS01, Observatoire National du Sport, Tunis 2020, Tunisie; [email protected] 4 Institut Supérieur du Sport et de l’éducation physique de Sfax, Université de Sfax, Sfax 3000, Tunisie 5 Medbase St. Gallen Am Vadianplatz, St. Gallen 9001, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 10 April 2019; Published: 12 April 2019 Abstract: This study investigated gender differences in performance and participation and the role of nationality during one century in one of the largest cross-country (XC) skiing events in the world, the ‘Vasaloppet‘ in Sweden. The total number of female and male athletes who finished (n = 562,413) this race between 1922 and 2017 was considered. Most of the finishers were Swedish (81.03% of women and 88.39% of men), followed by Norwegians and Finnish. The overall men-to-women ratio was 17.5. A gender nationality association was observed for participation (χ2 = 1,823.44, × p < 0.001, φ = 0.057), with the men-to-women ratio ranging from 6.7 (USA) to 19.1 (Sweden). For both genders, the participation (%) of Swedish decreased, and that of all other nationalities (except Swiss) increased across years. -

Td Nominations for Long Distance Races 2020-2021

TD NOMINATIONS FOR LONG DISTANCE RACES 2020-2021 Date Site Race 2020-21 Proposal TD 27.11.2020 Livigno (ITA) 15 CT Po Team Tempo - Ski Classics (ITA) Robert Peets (EST) 29.11.2020 Livigno (ITA) 35 CT Prologue - Ski Classics (ITA) Robert Peets (EST) 20.12.2020 La Venosta (ITA) 45 & 30 Km CT La Venosta - Ski Classics (ITA) Uros Ponikvar (SLO) 16.01.2021 St. Moritz (SUI) 42 CT La Diagonela - Ski Classic (SUI) Matthey Claude (SUI) 23.01.2021 Toblach-Cortina (ITA) 50 CT Toblach-Cortina - Ski Classics (ITA) Thomas Granlund (SWE) 10.04.2021 Setermoen-Bardufoss (NOR) 50 CT Reistadløpet Bardufoss Ski Cl (NOR) Fred Arne Jackobsen (NOR) 17.04.2021 Ylläs-Levi (FIN) 67 km CT Ylläs-Levi, Ski Classic Final (FIN) Thomas Granlund (SWE) Worldloppet 04.01.2021 Changchun (CHN) 50 CT Vasaloppet-China (CHN) Georg Zipfel (GER) 23.-24.01.2021 Lienz (AUT) 42 CT/ 42 FT Dolomitenlauf (AUT) Thomas Unterfrauen (AUT) 31.01.2021 Moena-Cavalese (ITA) 70 CT Marcialonga (ITA) Michel Rainer (ITA) 06-07.02.2021 Oberammergau (GER) 50 CT Koenig Ludwig Lauf (GER) Rainer Kuchler (GER) 07.02.2021 Sapporo (JAP) 50 FT Sapporo Int. Ski Marathon (JPN) Akira Wada (JPN) 13-14.02.2021 Lamoura-Mouthe (FRA) 56 CT / 68 FT La Transjurassienne (FRA) Guy Magand (FRA) 14.02.2021 Bedrichov (CZE) 50 CT Jizerska Padesatka (CZE) Petr Mach (CZE) 21.02.2021 Otepaa-Elva (EST) 63 CT Tartu Maraton (EST) Vahur Leemets (EST) 27-28.02.2021 Lahti (FIN) 50 CT / 50 FT Finlandia Hiihto (FIN) Jussi Prykaeri (FIN) 20-21.02.2021 Gatineau (CAN) 51 CT / 51 FT Gatineau Loppet (CAN) Rene Pomerleau (CAN) 27.02.2021