Vasaloppet Final Draft 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: the (Engadin Ski Marathon)

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2017, Article ID 9821757, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9821757 Research Article The Russians Are the Fastest in Marathon Cross-Country Skiing: The (Engadin Ski Marathon) Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis,1,2 Jan Heller,3 and Beat Knechtle4,5 1 Exercise Physiology Laboratory, Nikaia, Greece 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Metropolitan College, Athens, Greece 3Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 4Gesundheitszentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland 5Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence should be addressed to Beat Knechtle; [email protected] Received 20 April 2017; Accepted 17 July 2017; Published 21 August 2017 Academic Editor: Laura Guidetti Copyright © 2017 Pantelis Theodoros Nikolaidis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. It is well known that athletes from a specific region or country are dominating certain sports disciplines such as marathon running or Ironman triathlon; however, little relevant information exists on cross-country skiing. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the aspect of region and nationality in one of the largest cross-country skiing marathons in Europe, the “Engadin Ski Marathon.” All athletes ( = 197,125) who finished the “Engadin Ski Marathon” between 1998 and 2016 were considered. More than two-thirds of the finishers (72.5% in women and 69.6% in men) were Swiss skiers, followed by German, Italian, and French athletes in both sexes. Most of the Swiss finishers were from Canton of Zurich (20.5%), Grisons (19.2%), and Berne (10.3%). -

Bringing the Birkebeiner Legacy to Life at the Birkie

For Immediate Release Contact: Nancy Knutson 715-634-5025 [email protected] Bringing the Birkebeiner Legacy to Life at the Birkie Descendants of Founding Birkie Skier Selected as 2019 Birkebeiner Warriors & Inga Hayward, WI (February 23, 2019) – The American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation is pleased to announce the selection of the trio of cross-country skiers who will depict two Birkebeiner Warriors and Inga, the mother of baby Prince Haakon. On February 23, 2019, William Andresen (Ironwood, MI), Carolyn Andresen Warren (Ironwood, MI), and David Andresen (Ironwood, MI) will portray Torstein, Skjervald, and Inga, respectively. Each year, in homage to the legacy of the race, a trio reenacts the historic trek of warriors Torstein and Skjervald, and Inga (mother of Prince Haakon) on wooden skis and in full costume along the entire 55K classic American Birkebeiner cross-country course. Inga and the Warriors will carry a baby doll along the race course, and pick-up a real baby “prince” prior to skiing down Main Street to the finish line. The portrayal is a true celebration of the roots, legacy and traditions of the race. What makes this year’s Inga and Warriors selection all the sweeter, is that the trio are the descendants of Karl Andresen, one of the original 35 founding American Birkebeiner skiers from 1973. Karl’s son, William (Torstein), skied in the first Kortelopet at the age of twelve and has since racked-up a total of seven Kortelopet races and eighteen American Birkebeiner races. Karl’s grandchildren, David (Skjervald) and Carolyn (Inga), have never experienced a year without a Birkie, including skiing in eleven Barnebirkie races each. -

2011 American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation

2016-2017 American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation Board Candidate Profile Information Candidate Name: Ian D. Duncan Address: 137 Nautilus Drive City: Madison State: WI Zip: 53705 Home Phone: 608-233-0962 Other Phone:_608-514-5596 (cell)__ E-Mail Address: [email protected] Years of Membership in the ABSF: Not sure Occupation: Professor, UW-Madison Please respond to the following question. Why are you interested in being a member of the ABSF Board of Directors and what knowledge and skills do you possess that can benefit the organization? In the early 1980’s I read about the American Birkebeiner while working as a research fellow at McGill University in Montreal. I had taken up cross country skiing in Montreal and had done the Canadian Ski Marathon a few times as well as the Riviere Rouge race. I was looking for a job and while UW-Madison was trying to recruit me, the thought of skiing the Birkie tipped the scale. Well, thirty two Birkie’s later, the race has become a major part of my adult life. My family is also involved and my older son is a Birkie skier. This year I was reminded of the special place of the Birkie when listening to WORT in the comfort of my condo as the 6-hour plus finishers were interviewed. The thing that impressed me most was the joy and enthusiasm of the many young male and female competitors who despite their exhaustion, laughed and recounted the fun of the race and that they would do it all again, ‘Now that’s something worth preserving and promoting I thought!’ As a veteran ski racer both in the North America and in Europe where I have done the Norwegian Birkie and the Marcialonga I know what it takes for a ski race to be successful (apart from good snow!) I ran the Birke Skiers for Cure Program in 2009-2012 and raised over $300K for MS research. -

37. Forum Nordicum 3 Deine Belohnung

3 7. Forum Nordicum 11. – 14.10.2016 www.lahti2017.fi/en/de Biathlon-König Martin Fourcade bei der Ehrung durch Rolf Arne Odiin. Rolf-Arne Odin honors Biathlon-King Martin Fourcade. (Foto: FN) Dein Sport. Deine Belohnung. 100% Leistung. 100% Regeneration. Durch das enthaltene wertvolle Vitamin B12 wird der Energiestoffwechsel, die Blutbildung und das Immunsystem gefördert sowie die Müdigkeit verringert. Eine abwechslungsreiche und ausgewogene Ernährung sowie eine gesunde Lebensweise sind wichtig! GREEtiNG Dein Sport. Janne Leskinen CEO, Secretary General Lahti2017 FiS Nordic World 37. Forum Nordicum 3 Deine Belohnung. Ski Championships Lahti will host the Nordic World Ski Championships in 2017 for a historic seventh time. We are extremely proud to be the first city to achieve this record. To celebrate our unique history, we decided to name the event the Centenary Championships. The Centenary Championships are both an exciting and carefully prepared world-class sports event and one of the festivities that celebrate the centenary of Finland’s independence. A rare occasion for us Finns – and hopefully for our international guests. Lahti offers an optimal setting for record-breaking performances. The traditional venue has undergone extensive renovation and is now a fully functioning stadium that meets today’s requirements. We are also proud to have Vierumäki Olympic Training Center as our athlete’s village that allows the athletes to unwind and focus all their energy on performing at their best. We hope that the 2017 World Championships will leave their mark on future decades of sports events in Lahti and in Finland. The event has gained a great deal of popularity among young people, and we will soon have a new generation of volunteers for sports events. -

2020 Participant Statistics

2020 Participant Statistics Slumberland American Birkebeiner – Skiers by Technique • 66% Skate Technique • 34% Classic Technique Kortelopet – Skiers by Technique • 57% Skate Technique • 43% Classic Technique Slumberland American Birkebeiner • 66% Skate Technique • 34% Classic Technique Slumberland American Birkebeiner & Kortelopet Raced Combined – by Technique • 63% Skate Technique • 37% Classic Technique Slumberland American Birkebeiner • 79% Men • 21% Women Kortelopet • 55% Male • 45% Female Prince Haakon • 38% Male • 62% Female American Birkebeiner, Kortelopet & Prince Haakon Races - Combined Skiers • 70% Male • 30% female -more- Oldest Registered Participants by Race • Kortelopet Men – Age 87 • Kortelopet Women – Age 79 • Slumberland American Birkebeiner Men – Age 86 • Slumberland American Birkebeiner Women – Age 76 Slumberland American Birkebeiner – Skier Recognition Participants 2020 • Birchleggers Skiing in 2020 (20+ More Birkie Races Skied) - 596 • Uberleggers Skiing in 2020 (30+ More Birkie Races Skied) – 354 Kortelopet -- Skier Recognition Participants 2020 • Skiløper – Ti (10+ Kortelopet Races Skied/Pronounced “tee”) – 202 • Skiløper -Tjue (20+ Kortelopet Races Skied/Pronounced “tu-a”) – 24 • Skiløper – Tretti (30+ Kortelopet Races Skied/Pronounced “tre-tee”) – 4 Slumberland American Birkebeiner International Participants by Country • Austria • France • United Kingdom • Czech Republic • Canada • Slovenia • Russia • Sweden • Iceland • Australia • Estonia • United States of America • Norway • Italy • Mexico • Vietnam • Denmark -

STATS EN STOCK Les Palmarès Et Les Records

STATS EN STOCK Les palmarès et les records Jeux olympiques d’hiver (1924-2018) Depuis leur création en 1924, vingt-trois éditions des Jeux olympiques d’hiver se sont déroulées, regroupant des épreuves aussi variées que le ski alpin, le patinage, le biathlon ou le curling. Et depuis la victoire du patineur de vitesse Américain Jewtraw lors des premiers Jeux à Chamonix, ce sont plus de mille médailles d’or qui ont été attribuées. Charles Jewtraw (Etats-Unis) Yuzuru Hanyu (Japon) 1er champion olympique 1000e champion olympique (Patinage de vitesse, 500 m, 1924) (Patinage artistique, 2018) Participants Année Lieu Nations Epreuves Total Hommes Femmes 1924 Chamonix (France) 16 258 247 11 16 1928 St Moritz (Suisse) 25 464 438 26 14 1932 Lake-Placid (E-U) 17 252 231 21 17 1936 Garmish (Allemagne) 28 646 566 80 17 1948 St Moritz (Suisse) 28 669 592 77 22 1952 Oslo (Norvège) 30 694 585 109 22 1956 Cortina d’Ampezzo (Italie) 32 821 687 134 24 1960 Squaw Valley (E-U) 30 665 521 144 27 1964 Innsbruck (Autriche) 36 1 091 892 199 34 1968 Grenoble (France) 37 1 158 947 211 35 1972 Sapporo (Japon) 35 1 006 801 205 35 1976 Innsbruck (Autriche) 37 1 123 892 231 37 1980 Lake Placid (E-U) 37 1 072 840 232 38 1984 Sarajevo (Yougoslavie) 49 1 272 998 274 39 1988 Calgary (Canada) 57 1 423 1 122 301 46 1992 Albertville (France) 64 1 801 1 313 488 57 1994 Lillehammer (Norvège) 67 1 737 1 215 522 61 1998 Nagano (Japon) 72 2 176 1 389 787 68 2002 Salt Lake City (E-U) 77 2 399 1 513 886 78 2006 Turin (Italie) 80 2 508 1 548 960 84 2010 Vancouver (Canada) 82 2 566 -

Lillehammer Der Ort Der Helden

Lillehammer Der Ort der Helden Der Bahnhofplatz dieser Ort trägt den Namen Johann Olav Koss. Johan Olav Koss war ein erfolgreicher Eisschnellläufer aus Norwegen. Er gewann unter anderem eine Goldmedaille an den Olympischen Spielen 1992 in Albertville. Jede Stunde kreuzen sich hier, am Johann Olav Koss Bahnhofplatz, die Züge. Die einen fahren Richtung Hauptstadt, die andere Richtung Norden. Zu jeder vollen Stunde fährt noch ein Regionalzug, der die umliegenden Dörfer bedient. Mitten auf dem Platz steht eine bescheidene Statue dieses norwegischen Olympiasiegers. Der Bahnhof liegt etwas am Rande der Stadt. Die Tommy Moe Strasse (Olympiasieger Ski Alpin, USA) führt zum Zentrum. Mit dem Bus, Georg Hackl Linie (Olympiasieger Rodeln, GER) dauert es etwa 10 Minuten um das Zentrum zu erreichen. Viel Spannendes gibt es unterwegs nicht zu sehen, einige Wohnhäuser, einen Kiosk und das Krankenhaus. Vor allem im Winter gibt es dort einiges zu tun, wenn viele Wintersportler mit grösseren oder kleineren Verletzungen eingeliefert werden. Der Gebärsaal trägt den Namen der Koreanerin Kim Yun-Mi. Sie gewann als 13-jähriges Mädchen olympisches Gold im Short Track. Damit ist sie die jüngste Gewinnerin einer Olympiamedaille. Das Spital liegt übrigens an der Emese Hunyady Strasse (Olympiasiegerin Eisschnelllauf, AUT). Das Zentrum dieser Stadt ist der Bjørn Dæhlie Platz. Bjørn Dæhlie war Langläufer, ist ein Held, eine Legende und Olympiasieger; mehrfacher Olympiasieger sogar. Er gewann acht Goldmedaillen, an drei Olympischen Spielen. Dazu gewann er noch viermal Silber. Der Platz ist eigentlich ein grosser Kreisel mit fünf Zubringern. In der Mitte des Kreisels steht ein grosser Springbrunnen. Rundum den Brunnen, dem im Winter wegen Gefriergefahr das Wasser abgestellt wird, stehen acht Statuen von Bjørn Dæhlie. -

Cross Country Marathon Calender 2018 / 2019 Date Race Location Country Distance Additionals Serie Homepage

Cross Country Marathon Calender 2018 / 2019 date race location country distance additionals serie homepage Sa. 24.11.18 Kiilopäähiihto Saariselkä / Kiilopää FIN 50 / 20 CL www.suomenlatu.fi/tapahtumia/kiilopaahiihto/uutiset.html Sa. 01.12.18 Sgambeda Livigno ITA 30 FT www.lasgambeda.it So. 16.12.18 Kannelberglauf Hermsdorf D 20 CL www.sportverein-hermsdorf.de Sa. 29.12.18 Rymmarloppet Arvidsjaur SWE 40 CL www.skidor.com Mo. 31.12.18 Silvesterlanglauf Kössen AUT 22 FT www.nordic-center.com So. 30.12.18 Risouxloppet St. Lupicin / Jura FRA 25 / 10 FT www.skiclub-saintlupicin.jimdo.com Fr. 04.01.18 China Vasalauf Changchun CHN 50 / 25 CL 1 www.vasaloppetchina.com Fr. 04.01.19 Bedrichovska Night LM Bedrichov / Liberec CZE 30 / 17 FT www.ski-tour.cz Sa. 05.01.19 Bedrichovska Night LM Bedrichov / Liberec CZE 30 / 17 CL www.ski-tour.cz Sa. 05.01.19 Budorrennet Loten NOR 46 CL www.kondis.no Sa. 05.01.19 Nordic Ski Marathon Bruksvallarna SWE 42 / 21 CL www.skidor.com So. 06.01.19 Attraverso Campra Olivione CH 21 FT 10 www.swissloppet.com So. 06.01.19 Base Tuono Marathon Passo Coe / Folgaria ITA 30 FT www.gronlait.it So. 06.01.19 La Ronde des Cimes Les Fourgs / Jura FRA 30 / 10 FT www.marathonskitour.fr So. 06.01.19 Alpe D'Huez Marathon Alpe D'Huez Oisans FRA 30 FT www.ffs.fr So. 06.01.19 AXA Skimarathon Sagmyra SWE 42 / 21 CL www.skidor.com Fr./So. 11.-13.1.19 Tour de Ramsau Ramsau / Dachstein AUT Sa. -

A Spectator's Guide to the American Birkebeiner

THEVISITOR A Spectator’s Guide to the American Birkebeiner BIRKIE 2016 IINN--HHOOUUSSEE EEXXPPOO Thurs • Fri • Sat • Sun 9-7 9-9 8-7th 9-4nd FeFebb 18 19th -- 21st 22 In The In The Factory expertsonhIn Theand SPEND North SPEND North SPEND North Face Face to help during the expoFace ! $350 merchandise $250 merchandise $150 merchandise get a Jester get a logo get a beanie backpack worth $30* worth $65* sweatshirt worth $55* *While supplies last Styles and colors may vary Extended Store Hours: Thurs: 9-7 • Fri: 9-9 • Sat: 8-7 • Sun: 9-3 Select Race Select ski equipment, men’s/women’s Wax accessories & clothing sportswear,& boots fleeze jackets Best Price 20-60% OFF POST-BIRKIEGuarantee! BUCKS 20-40% OFF $20-$35-$50 OFF on ANY Purchase!* *Receive $20 off of any purchase over $100 *Receive $35 off of any purchase over $175 *Receive $50 off of any purchase over $250 WITH THIS COUPON $5-$10-$15 OFF on POST-BIRKIE• SOME EXCLUSIONS MAYAPPLY • LIMIT ONE COUPON BUCKS PER CUSTOMER • ANY Purchase!* • MUST PRESENT COUPON AT TIME OF PURCHASE • * Receive $5 off on anyNO purchaseT VALID ONov SALEer $50 ITEMS WITH THIS COUPON • • Couponthru valid SUNDAY, SUNDAY, March Feb 1st, 22nd 2015 * Receive $10 off of any purchase over $75 * Some exclusions may apply * Limit one coupon per customer Coupon valid * Receive $15 off opf any purchase over $100 * Must present coupon at time of purchase * Not valid on sale items Feb 20th - 28th 2016 10579N Main Street, Hayward AtAt the thef finishinish lin linee ofof the the Birkie! Birkie! 715-634-4447 Shop online at www.OutdoorVenturesHayward.com 2 Hayward’s Original Visitor Magazine COMMENT Ok, this isn’t your grandmother’s Visi- tor you’re holding in your hands. -

The Effect of Sex and Performance Level on Pacing in Cross-Country Skiers: Vasaloppet 2004‐2017

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 The effect of sex and performance level on pacing in cross-country skiers: Vasaloppet 2004‐2017 Nikolaidis, Pantelis Theodoros ; Villiger, Elias ; Knechtle, Beat Abstract: Background Pacing, defined as percentage changes of speed between successive splits, hasbeen extensively studied in running and cycling endurance sports; however, less information about the trends in change of speed during cross-country (XC) ski racing is available. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the effect of performance (quartiles of race time (Q), with Q1 the fastest andQ4 the slowest) level on pacing in the Vasaloppet ski race, the largest XC skiing race in the world. Methods For this purpose, we analyzed female (n = 19,465) and male (n = 164,454) finishers in the Vasaloppet ski race from 2004 to 2017 using a 1-way (2 gender) analysis of variance with repeated measures to examine percentage changes of speed between 2 successive splits. Overall, the race consisted of 8 splits. Results The race speed of Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 was 13.6 ± 1.8, 10.6 ± 0.5, 9.2 ± 0.3, and 8.1 ± 0.4km/h, respectively, among females and 16.7 ± 1.7, 13.1 ± 0.7, 10.9 ± 0.6, and 8.9 ± 0.7km/h, respectively, among males. The overall pacing strategy of finishers was variable. A small sex × split interaction on speed was observed (2 = 0.016, p < 0.001), with speed difference between sexes ranging from 14.9% (Split 7) to 27.0% (Split 1) and larger changes in speed between 2 successive splits being shown for females (p < 0.001, 2 = 0.004). -

Cross-Country Skating: How It Started

Cross-Country Skating: How it Started Few sports have changed as rapidly and dramatically as did cross-country skiing in the 1980s. For more than a hundred years cross-country competitors had universally raced with the ancient diagonal stride, alternately kicking and gliding. In retrospect, it was remarkable that no one saw how much faster a skier could move if he propelled himself by skating with his skis, in the manner of an ice skater. America’s Bill Koch first observed the skate step at a Swedish marathon, then applied it to win the 1982 World Cup of Cross Country skiing. Immediately the sport was engulfed in controversy over the new technique. Within five years, World Championship and Olympic cross-country skiing was utterly transformed. Now there were as many medals for Freestyle, in which skating is permitted, as would be awarded for Classic, in which skating was prohibited. And in three more years, the freestyle revolution was so powerful that it led to the Pursuit competition, with a totally new way of starting racers and climaxing in a telegenic finish. No one was better situated to observe the revolution than Bengt Erik Bengtsson, Chief of the Nordic Office of the Swiss-based International Ski Federation (FIS) from 1984 to 2004. The use of a skating technique to ski across snow is hardly new. In the 1930s, when bindings were adaptable to both downhill and cross-country, skiers commonly skated across flat areas, in the style of an ice skater. For a long time cross-country ski racers skated in order to take advantage of terrain or to combat poor wax, although it was difficult to do over grooved tracks and in a narrow corridor. -

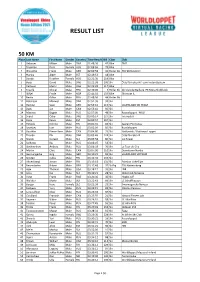

Home Edition 2021 Result List.Xlsx

RESULT LIST 50 KM Place Last Name First Name Gender Country Time Result BIB Class Club 1 Gebauer Mikael Male SWE 01:48:36 47 Bike TMT 2 Trueman Doris Female AUS 02:08:04 79 Bike 3 Wünsche Frank Male GER 02:09:58 41 Roller Ski TSV 90 Neukirch 4 Närska Alger Male EST 02:19:53 18 Bike 5 Bundy Heather Female AUS 02:22:30 119 Bike 6 Boija David Male SWE 02:22:38 100 Ski Österfärnebo IF/Team InstantSystem 7 Carlsson Martin Male SWE 02:23:28 117 Bike 8 Traullé Olivier Male FRA 02:40:00 9 Roller Ski Ski Club de Beille & IFK Mora Skidklubb 9 Stifjell Frode Male NOR 02:44:02 103 Bike Skorovas IL 10 Bertin Gilles Male FRA 02:48:56 44 Roller Ski 11 Robinson Maxwell Male SWE 02:51:36 39 Ski 12 Herling Sven Male GER 02:53:16 115 Ski SAUERLAND SKI TEAM 13 Basta Jan Male CAN 02:53:44 92 Ski 14 Маслов Вадим Male RUS 02:57:00 48 Ski Russialoppet - MSU 15 Svärd Oskar Male SWE 03:00:14 127 Ski Tvärreds IF 16 Kiple Kaivo Male EST 03:00:57 107 Ski 17 Pohjola Kimmo Male FIN 03:01:31 82 Ski Saaren Ponnistus 18 Savelyev Ivan Male RUS 03:02:09 85 Ski Russialoppet 19 Gauthier Pierre-Yves Male CAN 03:04:00 25 Ski Nakkertok / Gatineau Loppet 20 Thorén Pär Male SWE 03:05:46 124 Ski Österfärnebo IF 21 Slivnik Gorazd Male SLO 03:05:58 86 Ski Ice Power 22 Soldatov Ilya Male RUS 03:06:07 54 Ski 23 Ovchinnikov Andrey Male RUS 03:06:39 76 Ski Le Tour de Chiz 24 Martin Chris Male CAN 03:07:00 110 Ski Downtown Nordic 25 Gerstengarbe Jörg Male GER 03:10:21 93 Ski SAUERLAND SKITEAM 26 Sjösten Jukka Male FIN 03:12:40 135 Ski 27 Ahvenlampi Anton Male FIN 03:13:18 131 Ski Paimion