1 A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon Improvement Scheme Registration ID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Doubleclick Insert Picture"

Bungalow 5, Catthorpe Manor, Lilbourne Road, Catthorpe, Lutterworth, Leicestershire, LE17 6DF "DoubleClick Insert Picture" Bungalow 5, Catthorpe Manor, Lilbourne Road, Catthorpe, Lutterworth, LE17 6DF Offers in Excess of: £365,000 A nicely presented four bedroom detached dormer bungalow situated in the grounds of Catthorpe Manor Estate with landscaped mature gardens, single garage and no onward chain. Features • Detached bungalow • Two bedrooms with walk-in wardrobes • Spacious living accommodation • Ground floor bedroom and wet room • Family bathroom • Landscaped gardens • Popular village location • Farm shop within walking distance • Single garage Location Catthorpe is a small Leicestershire village around 5 miles to the east of Rugby with a church and a thriving, well stocked and popular farm shop. The property itself sits within the former grounds of Catthorpe Manor, a recently refurbished hotel which has a popular restaurant which is open to all. It offers excellent access to the extensive motorway network surrounding Leicestershire as well as a Virgin high-speed train service from Rugby to Euston in around 50 minutes. Birmingham International airport can be reached in under 40 minutes from Catthorpe. The range of schooling is superb with independent schools like Bilton Grange, Princethorpe and of course the famous Rugby School is within easy reach. Reputable state schools are available in Swinford and Lutterworth if required. Outside The property is approached by a tarmacadam pathway, which leads to a sandstone patio wall, edged with terracotta brick work, and a dwarf wall. The front garden is screened by a variety of well-tended shrubs and trees including a blue spruce. To one side of the property there is a mature planted border, with established hydrangea shrubs and climbing honeysuckle. -

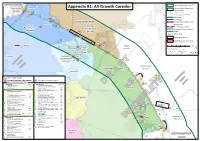

Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor

5km Distance buffer from A5 STAFFORDSHIREA 1 5 1 Polesworth Tamworth Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor Areas of Recent Major Road Improvements: Borough 2 A A5 / A444 / A47 - MIRA 4 2 47 A B M1 / M6 / A14 - Catthorpe Interchange (to be completed Autumn 2016) 69 3 4 M 5 4 4 4,5 A Motorways Trunk Roads 3 7 8 ! 42 Current Railway Stations and M LEICESTERSHIRE Atherstone Earl Shilton Railway Lines North 6 7 Hinckley 69 ! Warwickshire 6 A5 M Future Railway Stations and Bosworth HS2 Route (Phases 1 and 2) Borough A47 Borough Canals 21 25 Urban Areas A M 1 County Boundaries 8 A 22 Hinckley 11 District/Borough Boundaries 25 (Coloured administrative areas show "LEP City Deal" areas.) 13,14,15,16 23 10 9 A47 0 1 2 3 4 5 1:55,000 9 24 (When printed at 10 12 Blaby A1 paper size.) SOLIHULL 11 Kilometres Nuneaton District This map is for illustrative purposes only. ´ 12 © Crown Copyright and database right 2015. Ordnance Survey 100019520. 4 Produced by the WCC Corporate 4 4 GIS Team, A 13 69 25 June, 2015. M 15 14 Coleshill Nuneaton 16 and Bedworth A 1 17 5 M Borough Harborough WARWICKSHIRE District Bedworth 26 M6 28 D Current Employment Sites 29 D Future Employment Sites / Major Expansion 8 Future Major Housing Developments Lutterworth Red text signifies those sites without full planning permission 9 6 M Future Employment Staffordshire: Figures: Warwickshire: Housing Units: 27 Tamworth Borough: = Development Site North Warwickshire Borough: Rugby A45 * in Warwickshire 1 Relay Park - 1 Land on South Side of Grendon Road 143 2 Centurion Park 421 * 2 Orchard, Dordon 360 Borough 3 Dairy House Farm, Spon Lane 85 Warwickshire: 4 Land at Old Holly Lane including Durno's 620 A 4 North Warwickshire Borough: Nurseries 4 3 Kingsbury Link - 5 Rowland Way 88 4 4 Hall End Farm 750 6 Britannia Works, Coleshill Road 54 5 Birch Coppice (Phases 1-3) (inc. -

M1 Junction 19 Improvements

Safe roads, Reliable journeys, Informed travellers Junction 19 Improvements M1 Public Consultation Public Consultation An Executive Agency of the The Project Objectives The existing junction currently suffers from the following problems: • congestion, delays and long queues • accidents sometimes resulting in serious injuries and fatalities • confl icts between local and long distance traffi c • creates a barrier to pedestrians, cyclists and horse riders. If no improvements are made these problems will get worse. Pub We aim to relieve congestion at the junction, ubcCosuao making the roads safer and decreasing journey times, whilst minimising the environmental impacts of the scheme. li c The current problems can be resolved by changing the junction layout and separating local and long Co distance traffi c. n su lt a ti o n Update on Progress 2000 A study commenced to look at possible improvements to the junction. 2002 Public Consultation on a number of junction options. 2003 Secretary of State announced a Preferred Scheme - now known as the Blue Junction. 2004 Public Exhibition to present Local Road Network (LRN) options. 2004-2007 Further options identifi ed which may have advantages over the 2003 Preferred Scheme. 2008 Public Consultation on the current options. Current Improvement Options We have developed three possible motorway junction options and three Local Road Network (LRN) options. These can only be combined as follows: Blue Junction and Green LRN Brown Junction and Green LRN Red Junction and Green LRN Red Junction and Orange LRN -

ROMANO-BRITISH RURAL OCCUPATION at the CATTHORPE INTERCHANGE, M1 JUNCTION 19, LEICESTERSHIRE Nicky Garland

ROMANO-BRITISH RURAL OCCUPATION AT THE CATTHORPE INTERCHANGE, M1 JUNCTION 19, LEICESTERSHIRE Nicky Garland Archaeological investigation undertaken between November 2013 and February 2014, at the Catthorpe Interchange, M1 Junction 19, Leicestershire, revealed evidence for two phases of Roman activity. A series of quarry pits was followed by two enclosures, droveways and field boundary ditches, indicating the presence of a probable agricultural complex. A moderate assemblage of Roman pottery was recovered, with more closely datable forms suggesting a Middle Roman date for the assemblage as a whole. Extensive medieval ridge-and-furrow agriculture had truncated much of the earlier archaeological evidence. INTRODUCTION Between November 2013 and February 2014, Cotswold Archaeology (CA) undertook a programme of archaeological mitigation for the Highways Agency at the Catthorpe Interchange, Junction 19 of the M1 Motorway, Leicestershire (site centred on NGR: 456021 278863; Fig. 1). The work, undertaken ahead of upgrades to the motorway junction and local road network, consisted of a strip, map and sample excavation (with which this paper is concerned), a trial trench evaluation (CA 2015a), a watching brief and an earthwork survey. The surrounding landscape is comprised mainly of arable and pasture fields between the villages of Swinford and Catthorpe, Leicestershire (Fig. 1). The area of excavation lies at approximately 115m AOD, with the ground level dropping away to the south. The underlying geology for this area is dominated by the Blue Lias Clay and Charmouth Mudstone Formation, formed in the Jurassic and Triassic Periods (BGS 2017). The superficial geology along the northern and eastern boundary of the site consists of glacial till, with some evidence for river terrace deposits to the south. -

Local Amenities & Places of Interest

Local Amenities & Places of Interest Within walking distance Catthorpe Farm Shop Situated here in Catthorpe village, a traditional family run mixed farm and tea room. Also selling gift items in the shop and in the florists next door. A: Main St, Catthorpe, Leicestershire. LE17 6DB T: 01788 869002 W: www.manorfarmcatthorpe.co.uk All Saints Church Beautiful grade one listed building in the heart of Lilbourne. Please contact to arrange visits. A: Station Rd, Lilbourne, Northamptonshire. CV23 0SX (1.3 miles) T: 01788 822147 W: www.lilbourne.com Lilbourne Castle & Lilbourne Gorse Lilbourne Castle is an impressive Norman earthwork motte and bailey fortress, founded by Robert, earl of Leicester. The 11th century motte, encased by its ditch, protects the two small baileys, which are powerfully defended with high ramparts, ditches and counterscarp banks. A: Located in the village centre, off Station Road. OS Map Grid Reference: SP56117747. (Lilbourne Gorse OS Map Grid Reference: SP55337714) Within 15 Miles Rugby School Tours & Museum ‘The school behind the game.’ See the influence of the school in the sporting and cultural heritage of this sport. Visits by prior arrangement only. A: 10 Little Church Street, Rugby, Warkwickshire. CV21 3BY (4.8 miles) T: 01788 556169 W: www.rugbyschool.co.uk The Webb Ellis Rugby Football Museum. Established in the 1980s, the museum houses a rich collection of international rugby memorabilia and tells the story of the game, the ball and the building. Its prestige attracts fans of rugby from all over the world. A: 5 St. Matthew Street, Rugby, Warwickshire. CV21 3BY. (5 miles) T: 01788 567777 W: www.webb-ellis.co.uk Rugby Theatre Amateur theatre, with regular shows, from compelling modern dramas to farce and musical theatre. -

Integrated Transport: a New Generation of Interchanges

Integrated transport A new generation of interchanges www.bettertransport.org.uk Contents Executive summary Executive summary 3 Transport networks should be efficient, affordable, Funding and support accessible and comprehensive. Good modal Introduction 4 A Bus and Coach Investment Strategy is long overdue. interchanges are central to creating such networks. The Government should develop a multi-year bus Planning and interchanges 6 and coach investment strategy to sit alongside other That much of the country lacks such systems is the Case study - Thurrock 12 transport investment, such as the Road Investment result of disjointed and reductive transport planning Strategy and rail’s High Level Output Specification. Case study - Catthorpe Interchange 16 and investment. Despite in-principle support and a number of small national initiatives, there has been Case study - Luton North 19 A joint Department for Transport (DfT), Department a widespread and ongoing failure to link transport for Housing, Communities and Local Government Other opportunities for improved connectivity 23 networks and modes. The resulting over-reliance on fund should be established to support the delivery cars is engendering negative social, economic and Conclusions and recommendations 26 of national priority interchanges and to fund regional environmental ramifications. These consequences assessment of interchange opportunities. Cross- References and image credits 30 unfairly disadvantage those who do not have a car government working should also examine how better and lead to perverse spending decisions to address interchanges can contribute to policies such as the the resulting congestion. Industrial Strategy. We need a better way forward. This report makes the Infrastructure schemes funded via the Road Investment case for a new generation of transport interchanges. -

M1 Junction 19 Improvement Catthorpe Interchange Leicestershire

M1 Junction 19 Improvement Catthorpe Interchange Leicestershire Archaeological Strip, Map and Sample Excavation and Watching Brief for Skanska on behalf of Highways Agency CA Project: 669031 CA Report: 17144 June 2017 M1 Junction 19 Improvement Catthorpe Interchange Leicestershire Archaeological Strip, Map and Sample Excavation and Watching Brief CA Project: 669031 CA Report: 17144 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 22.3.17 Nicky Sarah Internal QA SLC Garland Cobain review B 26.04.17 Nicky Sarah Internal QA KEW Garland Cobain review C 20.06.17 Nicky Sarah Internal QA KEW Garland Cobain review This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology M1 Junction 19 Improvement, Leicestershire: Archaeological Excavation CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 4 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 5 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 7 4. METHODOLOGY -

Harborough District Council Settlement Profile: Swinford

Harborough District Council Settlement Profile: Swinford May 2015 General Introduction This settlement profile has been prepared as part of the evidence base for the preparation of the new Local Plan. The new Local Plan, which will cover the period 2011 – 2031, will review and replace existing Core Strategy policies. New evidence in the Strategic Housing Market Assessment (2014) shows that the number of new homes needed annually across the District to 2031 is substantially higher than the figure set out in the Core Strategy. The new Local Plan will set out a strategy to meet these higher housing numbers, whilst ensuring that sustainable economic development is supported, infrastructure is delivered, local communities are protected, environmental capacity is respected, the quality of the built environment and heritage assets are protected and the level of development is not disproportionate to the size of the settlement and the level of services. This profile seeks to summarise currently available evidence in relation to the settlement which, along with other evidence, will be used in determining the appropriate amount of development to be directed to the settlement to 2031. The profile does not seek to set out future policy as this will be done through the new Local Plan and any reference to Core Strategy policies is to provide context only. Section D of the profile sets out the findings of the Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) for the settlement. It should be noted that the sites shown are not allocations and their inclusion in no way implies that planning permission for housing will be granted. -

Volume 82 – 1988

TRANSACTIONS OF THE LEICESTER LITERARY & PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Tower Karst in Southern China Nuclear Test Verification East Midlands Airport S. C. Mason Dartington Chemistry and Society Lower Lias at Catthorpe Volume 82 August 1988 ISSN 0141 - 3511 TRANSACTIONS OF THE LEICESTER LITERARY AND PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 82 August 1988 CONTENTS THE SCIENCE OF VERIFICATION 1 Presidential Address by M.A. Khan DARTINGTON - A UTOPIAN COMMUNITY 3 D. Davis THE CONCEPTION AND OPERATION OF THE EAST MIDLANDS AIRPORT 7 E. Dyer MOLECULES AND ME - CHEMISTRY AND SOCIETY 9 R. Malpas THE LAST OF THE AMATEURS; S. C. MASON, CBE, DIRECTOR OF 15 EDUCATION FOR LEICESTERSHIRE, 1947-71 D.K. Jones THE TOWER KARST OF SOUTHERN CHINA 1 7 A.C. Waltham THE LOWER LIAS AT CATTHORPE, SOUTH LEICESTERSHIRE 21 D.M. Blake and R.G. Clements PRESIDENT'S REPORT, 1987-88 27 PROGRAMME FOR 146th SESSION 28 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE GEOLOGY SECTION 29 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE NATURAL HISTORY SECTION 30 MEMBERSHIP LIST 1987-88 33 Cover picture: Tower karst on the Li River, Guangxi, China. © Copyright: The Leicester Literary and Philosophical Sodety, 1988 Published by the Leicester Lit,erary and Philosophical Society, c/o Leicestershire Museums Service, 96 New Walk, Leicester LE1 6TD Transactions of the Leicester Literary & Philosophical Society Volume 82, 1988 THE SCIENCE OF VERIFICATION Presidential Address by Dr M, A, Khan delivered on 5th October 1987 The "verification" of the title refers to In 1963, the Limited Test Ban Treaty that of a Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (NTBT), (LTBT) was signed by 120 nations (but one of the most urgent and difficult excluding France) prohibiting nuclear diplomatic issues of the day. -

Display PDF in Separate

THE WARWICKSHIRE AVON CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY Notional Rivers Authority SEVERN TRENT REGION I Information Centre I Head Office Class N o .... I «« « * • « Accession No 4kJx£i&;> WARWICKSHIRE AVON CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT The Information Centre National Rivers Authority Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol BS12 4UD ! I Due for return s 'H m National Rivers Authority 2,3// t f °?S ■ The current that with gentle Lower Severn Area murmur glides.” Riversmeet House Newtown Industrial Estate I William Shakespeare Northway Lane Tewkesbury Glos GL20 8JG ■ ENVIRONMENT AGENCY This repon r I & 0 9 9 8 3 4 ............... J Warwickshire Avon Catchment Management Plan Consultation Report March 1994 FOREWORD The National Rivers Authority was created in 1989 to preserve and enhance the natural water environment and to protect people from flooding. In its role as ‘Guardian of the Water Environment’, the NRA is committed to preparing a sound plan for the future management of the region’s river catchments and consulting with those who have an interest. This Consultation Report is the first stage in this process "for the Avon Catchment. It provides a framework for consultation and also a means of seeking commitment from those involved to realise the full environmental potential of this special catchment. We look forward to receiving comments and contributions from interested organisations and individuals. These will enable a Final Plan to be produced, balancing the conflicting demands placed upon the natural water environment. Richard Bailey Area Manager Lower Severn Area WARWICKSHIRE AVON CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT CONTENTS PAGE No. -

Accompanying Note

Rural Economy Planning Toolkit Companion Document Instructions for Using the Toolkit Useful Context Information Produced by: Funded by: Rural Economic Development Planning Toolkit This document explains how to use the toolkit in greater detail and sets out some of the broader context relevant to the development of the toolkit. Its sections are: Instructions for Using the Toolkit Economic Development Context The Emerging National Framework for Planning and Development The assessment of planning applications for rural economic development: designated sites and key issues for Leicestershire authorities What makes a good rural economic development planning proposal? Case Studies Parish Broadband Speeds The Distribution and Contribution of Rural Estates within Leicestershire Attractions in Leicester and Leicestershire Instructions - Using the Toolkit The toolkit is in the form of an interactive PDF document. Most of the text is locked, and you cannot change it. Throughout the toolkit, though, comments, information and responses are asked for, and boxes you can type in are provided. You are also asked to select 'traffic lights' – red, amber or green. It is important to understand that, if you start with a blank copy of the toolkit, the first thing you should do is save it with a different name using the 'Save as Copy' command in Acrobat Reader. This means you have now created a version of the toolkit for the particular project you are working on, and still have the blank copy of the toolkit for another time. Let's assume you have saved your copy of the PDF file as 'Project.pdf' – every time you save again you will save all of the additions and traffic light choices you have made. -

Residential Development Site Outline Planning Permission for 50 Village Homes Approximate Distances London St Pancras Approx

Welham lane | Great BoWden | leicestershire Residential Development Site outline planning permission for 50 village homes AppRoximAte DiStAnceS London St Pancras approx. 60 mins by train Leicester – 16 miles • Catthorpe Interchange – 18 miles Market Harborough Station – 1.5 miles • Uppingham – 13 miles Oakham – 19 miles • Northampton – 20 miles Rugby – 22 miles • East Midlands Airport – 36 miles • outline planning permission for 50 dwellings • Gross Site Area: 22 acres (8.92 hectares) • planning area approx 7.84 acres LOCATION The development site is ideally located on the edge of Great Bowden and less than 2 miles from the The upgraded Catthorpe Motorway Interchange (A14/M1/M6) is only 18 miles away to the west. centre of Market Harborough. Great Bowden is an affluent and picturesque village in Leicestershire About 1.5 miles is Market Harborough train station providing regular return train services to London surrounded by attractive undulating countryside. The location provides a rural setting that benefits St Pancras International Railway Station with an average journey time of approximately one hour. from excellent commuter links. In the village there is a good range of amenities including a village Within close proximity to the site are several Primary and Secondary schools including: store and highly popular delicatessen with tea room, two public houses and a Church. Market Harborough provides further retail and leisure facilities including supermarkets as well as a good • Great Bowden Church of England Primary School (Ofsted Outstanding) – 500m range of independent stores, a small theatre, leisure centre and a good selection of restaurants and • Robert Smyth Academy – 1.5 miles bars.