Mottes & Ringworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd ANGOR UNIVERSITY Excavations, July and August 2013 Karl, Raimund; Waddington, Kate Published: 01/01/2015 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Karl, R., & Waddington, K. (2015). Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations, July and August 2013: Interim report. (Bangor Studies in Archaeology; Vol. 12). Bangor University. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations July and August 2013 Interim Report Kate Waddington and Raimund Karl Bangor: Gwynedd, January 2016 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 12 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 1 2 Also available in this series: Report No. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Barby Parish Council Notice of Meeting

KILSBY PARISH COUNCIL NOTICE OF MEETING To members of the Council: You are hereby summoned to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council to be held in Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. Please inform your Clerk on 07581 490581 if you will not be able to attend. Members of the public and press are invited to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council and to address the Council during its Public Participation session which will be allocated a maximum of 20 minutes. On……. TUESDAY 1st October, 2019 at 7.30pm In the Kilsby room of the Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. 24th September, 2019. Please note that photographing, recording, broadcasting or transmitting the proceedings of a meeting by any means is permitted without the Council’s prior written consent so long as the meeting is not disrupted. (Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014). Please make yourself known to the Clerk. Parish Clerk: Mrs C E Valentine, 20 Styles Place, Yelvertoft, Northamptonshire,NN6 6LR ______Tel 07581 490581 e-mail [email protected]___________ 1 APOLOGIES 2 CO-OPTION to fill CASUAL VACANCIES 2.1 To note that there are two vacant seats on the Parish Council and to consider candidates who have expressed an interest in becoming a Councillor and co-opt a suitable candidate. 3 PUBLIC OPEN FORUM SESSION limited to 20 mins. 3.1 Public Open Forum Session Members of the public are invited to address the Council. The session will last for a maximum of 20 minutes with any individual contribution lasting a maximum of 3 minutes. -

SEMLEP Economic Plan

FIGURE 2: KEY ASSETS MAP LEICESTER LEICESTER AIRPORT Daventry International Rail Freight Terminal iCon BUNTINGTHORPE AIRFIELD & PROVING GROUND M1 M6 COVENTRY COVENTRY AIRPORT M45 DAVENTRY 4 M1 NORTHAMPTON 11 Silverstone Daventry SEMLEP Area M40 Local Authorities SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Towns within SEMLEP Towcester Towns and Cities outside SEMLEP Main Rail Routes 10 Motorways Banbury Major A Roads Waterways Brackley 2 Buckingham Bicester ecotown I N K S T L W E Airports S T E A Hospitals Bicester AYLESBURY VALE Colleges Science/Technology/Business Hubs CHERWELL Northampton Enterprise Zone 7 Silverstone Aylesbur y Priors Hall Park Corby LONDON OXFORD AIRPORT Millbrook Proving Ground Arla Dairy Universities / University Technical Colleges (UTC) OXFORD 1 University of Bedfordshire 2 University of Buckingham 3 Cran�eld University 4 University of Northampton 5 Open University 6 University Campus Milton Keynes 7 Bucks New University at Aylesbury 8 Central Bedfordshire UTC 9 Buckinghamshire UTC 10 Silverstone UTC 11 Daventry UTC 8 SECTION 1 \\ OVERVIEW SEMLEP \\ STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN 2015-2020 Priors Hall Park Corby Northampton Waterside Enterprise Zone PETERBOROUGH Colworth Science Park CORBY KETTERING Kettering Bedford i-Lab E A S T W E S T L I N K CAMBRIDGE BEDFORD 1 Sandy Cran�eld Technology Park MILTON KEYNES 3 Biggleswade 6 5 CENTRAL Stotfold BEDFORDSHIRE Millbrook Proving Ground 8 1 LUTON LONDON LUTON AIRPORT 9 LONDON STANSTED 7 AIRPORT y M1 Butter�eld Enterprise Hub A1(M) M40 London Luton Airport HEATHROW AIRPORT CITY AIRPORT LONDON Arla Dairy SEMLEP \\ STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN 2015-2020 SECTION 1 \\ OVERVIEW 9 1.4 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES 1.4.1. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

"Doubleclick Insert Picture"

Bungalow 5, Catthorpe Manor, Lilbourne Road, Catthorpe, Lutterworth, Leicestershire, LE17 6DF "DoubleClick Insert Picture" Bungalow 5, Catthorpe Manor, Lilbourne Road, Catthorpe, Lutterworth, LE17 6DF Offers in Excess of: £365,000 A nicely presented four bedroom detached dormer bungalow situated in the grounds of Catthorpe Manor Estate with landscaped mature gardens, single garage and no onward chain. Features • Detached bungalow • Two bedrooms with walk-in wardrobes • Spacious living accommodation • Ground floor bedroom and wet room • Family bathroom • Landscaped gardens • Popular village location • Farm shop within walking distance • Single garage Location Catthorpe is a small Leicestershire village around 5 miles to the east of Rugby with a church and a thriving, well stocked and popular farm shop. The property itself sits within the former grounds of Catthorpe Manor, a recently refurbished hotel which has a popular restaurant which is open to all. It offers excellent access to the extensive motorway network surrounding Leicestershire as well as a Virgin high-speed train service from Rugby to Euston in around 50 minutes. Birmingham International airport can be reached in under 40 minutes from Catthorpe. The range of schooling is superb with independent schools like Bilton Grange, Princethorpe and of course the famous Rugby School is within easy reach. Reputable state schools are available in Swinford and Lutterworth if required. Outside The property is approached by a tarmacadam pathway, which leads to a sandstone patio wall, edged with terracotta brick work, and a dwarf wall. The front garden is screened by a variety of well-tended shrubs and trees including a blue spruce. To one side of the property there is a mature planted border, with established hydrangea shrubs and climbing honeysuckle. -

Watermeadows Management Plan 2017-32 Acknowledgements

Watermeadows Management Plan 2017-32 Acknowledgements Watermeadows Management Plan 2017-32 The Watermeadows Landscape Management Plan has been written and compiled by Red Kite Network Limited on behalf of Cherwell District Council and South Northamptonshire District Council. Staff from the District Council and the local community have also contributed to the development of the Plan. Red Kite would like to acknowledge the support and assistance from the following people and organisations: Councillor Roger Clarke, South Northamptonshire Council Paul Almond, Street Scene and Landscape Manager at Cherwell District and South Northamptonshire Councils Brian Collins, Landscape Officer at Cherwell District and South Northamptonshire Councils Towcester Town Council Alex Rothwell, Paul Wilkanowski and Helen Chapman from the Environment Agency Towcester Wildlife Trust Group Dr James Littlemore, Senior Lecturer, and Students of Moulton College Further information about the Plan is available from: South Northamptonshire Council The Forum, Moat Lane, Towcester, Northants, NN12 6AD Tel: 01327 322 322 Acknowledgements | 2 Contents Technical overview 3.0 Where do we want to go? Executive summary 3.1 Introduction 19 1.0 Introduction, Context and Background 3.2 SWOT analysis 19 1.1 Statement of Significance 6 3.3 Evaluation 22 1.2 Background to Plan 6 3.4 The Future 23 1.3 Format of Plan 6 3.5 Intervention Areas 25 1.4 Purpose of Plan 7 3.6 Zones and Trails 26 1.5 Development of Plan 7 4.0 How are we going to get there? 1.6 Stakeholder Invovlement and Target -

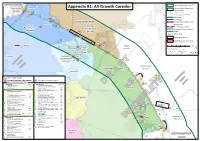

Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor

5km Distance buffer from A5 STAFFORDSHIREA 1 5 1 Polesworth Tamworth Appendix B1: A5 Growth Corridor Areas of Recent Major Road Improvements: Borough 2 A A5 / A444 / A47 - MIRA 4 2 47 A B M1 / M6 / A14 - Catthorpe Interchange (to be completed Autumn 2016) 69 3 4 M 5 4 4 4,5 A Motorways Trunk Roads 3 7 8 ! 42 Current Railway Stations and M LEICESTERSHIRE Atherstone Earl Shilton Railway Lines North 6 7 Hinckley 69 ! Warwickshire 6 A5 M Future Railway Stations and Bosworth HS2 Route (Phases 1 and 2) Borough A47 Borough Canals 21 25 Urban Areas A M 1 County Boundaries 8 A 22 Hinckley 11 District/Borough Boundaries 25 (Coloured administrative areas show "LEP City Deal" areas.) 13,14,15,16 23 10 9 A47 0 1 2 3 4 5 1:55,000 9 24 (When printed at 10 12 Blaby A1 paper size.) SOLIHULL 11 Kilometres Nuneaton District This map is for illustrative purposes only. ´ 12 © Crown Copyright and database right 2015. Ordnance Survey 100019520. 4 Produced by the WCC Corporate 4 4 GIS Team, A 13 69 25 June, 2015. M 15 14 Coleshill Nuneaton 16 and Bedworth A 1 17 5 M Borough Harborough WARWICKSHIRE District Bedworth 26 M6 28 D Current Employment Sites 29 D Future Employment Sites / Major Expansion 8 Future Major Housing Developments Lutterworth Red text signifies those sites without full planning permission 9 6 M Future Employment Staffordshire: Figures: Warwickshire: Housing Units: 27 Tamworth Borough: = Development Site North Warwickshire Borough: Rugby A45 * in Warwickshire 1 Relay Park - 1 Land on South Side of Grendon Road 143 2 Centurion Park 421 * 2 Orchard, Dordon 360 Borough 3 Dairy House Farm, Spon Lane 85 Warwickshire: 4 Land at Old Holly Lane including Durno's 620 A 4 North Warwickshire Borough: Nurseries 4 3 Kingsbury Link - 5 Rowland Way 88 4 4 Hall End Farm 750 6 Britannia Works, Coleshill Road 54 5 Birch Coppice (Phases 1-3) (inc. -

Official Guide and Map

TOWCESTER Official Guide and Map Delivered by Royal Mail to residents and businesses in Towcester. Also available from Town Council offices and to view online at www.towcester-tc.gov.uk Please tell the advertiser you saw them in the Towcester Official Guide and Map Award winning salon ‘Creative Salon Award’ Award winning stylists Salon and stylists state registered - National Federation of Hairdressing AWARD LOOKING YOU! Please visit our website for current offers and discounts or contact one of our friendly staff on: 01327 353143 [email protected] || www.flamehairstudios.co.uk Unit 4 - 6 Shire Court, 25 Richmond Road, Towcester, NN12 6EX 1 Please tell the advertiser you saw them in the Towcester Official Guide and Map TOWCESTER Official Guide and Map Issued by the authority of Towcester Town Council www.towcester-tc.gov.uk © Designed and Published by Local Authority Publishing Co. Ltd. www.localauthoritypublishing.co.uk View the online version at www.officialguides.co.uk Newman & Reidy Isuzu, the leading independent used car & van sales and service centre, in the South Northants and Milton Keynes areas. Established over 20 years. We have been selling New and Used vehicles since 2000 and over the years supplied in excess of 6,000 cars and vans all over the UK. Our service and reputation is outstanding, with many customers returning again and again for repairs, MOT’s and vehicle purchases. We look forward to being of service to the local community for many years to come, please feel free to come and put us to the test. The Name -

Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019

Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019. William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Lidar Image of Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire (© 2019 Chilterns Conservation Board) William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, 2019. Geophysical Survey at Desborough Castle, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, July 2019. William Wintle and Wendy Morrison August 2019 Introduction In 2017 the Chilterns Conservation Board was awarded a £695,600 grant by the Heritage Lottery Fund towards a four year £895,866 project to discover and conserve the hillforts of the Chilterns. The project is entitled “Beacons of the Past: Hillforts in the Chiltern Landscapes” and it aims to engage and inspire a large, diverse range of people to discover, conserve and enjoy the Chilterns' Iron Age hillforts and their prehistoric chalk landscapes. The nineteen Iron Age hillforts form one of the densest concentrations of hillforts in the country. The project is managed by Dr Wendy Morrison, supported by Dr Edward Peveler. A central component of the project is a detailed Lidar survey which will cover about 1400 km2. of the Chiltern Hills to provide new archaeological information, particularly for those areas covered by woodland. Important also is geophysical survey to investigate areas within and adjacent to a selected number of hillforts. Desborough Castle, situated within a large housing estate at High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, is one of the hillforts (or possible hillforts) selected for geophysical survey. A magnetometer (gradiometer) survey was conducted over areas of open grassland at and adjacent to Desborough Castle in early July with the aim of detecting archaeological features which might confirm an Iron Age date of certain earthworks and identifying potential locations for future limited trial excavation. -

Your Day in Northants 2017.Pdf

YourDayIN Northamptonshire www.yourdaynorthants.com The Stanwick Hotel West Street, Stanwick NN9 6QY Welcome to Northamptonshire Set in two acres of beautiful landscaped gardens and rolling countryside, The Stanwick Hotel offers four superb options for your ceremony: • Our Conservatory Garden Restaurant seats up to 80 guests and has stunning garden views • Our ‘Reflections’ suite can seat up to 130 for a Wedding Breakfast, or accommodate up to 250 for receptions • For a more intimate setting, our Dining Room is ideal for up to 16 guests • Our Wedding Pavilion, perfect for up to 130 guests in our lovely garden. 01933 622233 [email protected] www.thestanwickhotel.co.uk Barton Hall Rushton Hall Hotel &Spa Barton Seagrave, Kettering NN15 6SG Rushton NN14 1RR The most spectacular setting in the Midlands, Award Winning Barton Hall – The Perfect Venue Rushton Hall is a magnificent 15th Century Grade I Listed Stately Home Hotel and Spa, with luxurious en-suite Grade I listed Orangery licensed for Civil Ceremonies accommodation including four poster bedrooms. Exclusive Use available Beautiful historic gardens with lake for photographs. Charles Function Suite seating 180 guests The stunning Orangery is perfect for weddings from 80 29 beautiful bedrooms to 280 guests. 4 Red Star hotel and 3 Rosette restaurant. All set in Stunning Grounds Licensed for civil ceremonies. Exclusive use available. Plan your fairy tale day with our wedding team. 01536 515505 01536 713001 [email protected] [email protected] www.bartonhall.com www.rushtonhall.com Welcome to Northamptonshire The information in this brochure We are delighted that you are planning to hold your ceremony in is thought to be correct at Northamptonshire. -

M1 Junction 19 Improvements

Safe roads, Reliable journeys, Informed travellers Junction 19 Improvements M1 Public Consultation Public Consultation An Executive Agency of the The Project Objectives The existing junction currently suffers from the following problems: • congestion, delays and long queues • accidents sometimes resulting in serious injuries and fatalities • confl icts between local and long distance traffi c • creates a barrier to pedestrians, cyclists and horse riders. If no improvements are made these problems will get worse. Pub We aim to relieve congestion at the junction, ubcCosuao making the roads safer and decreasing journey times, whilst minimising the environmental impacts of the scheme. li c The current problems can be resolved by changing the junction layout and separating local and long Co distance traffi c. n su lt a ti o n Update on Progress 2000 A study commenced to look at possible improvements to the junction. 2002 Public Consultation on a number of junction options. 2003 Secretary of State announced a Preferred Scheme - now known as the Blue Junction. 2004 Public Exhibition to present Local Road Network (LRN) options. 2004-2007 Further options identifi ed which may have advantages over the 2003 Preferred Scheme. 2008 Public Consultation on the current options. Current Improvement Options We have developed three possible motorway junction options and three Local Road Network (LRN) options. These can only be combined as follows: Blue Junction and Green LRN Brown Junction and Green LRN Red Junction and Green LRN Red Junction and Orange LRN