Brahms' Piano Quartets in Their Music- and Social-Historical Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

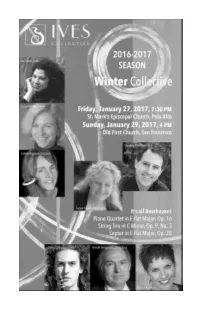

Ives 2017 Winter Program Book

IVES COLLECTIVE Season 2 Spring Collective Roy Malan, violin; Roberta Freier, violin Susan Freier, viola; Stephen Harrison, cello Elizabeth Schumann, piano Susanne Mentzer, mezzo soprano Friday,Please May 5,save 2017, these7:30 PM dates! St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Palo Alto Sunday, May 7, 2016, 4PM Old First Church, San Francisco Ottorino Respighi: Il Tramonto Johannes Brahms: Songs for Voice, Viola and Piano, Op. 91 Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60 Salon Concert Our Salon series, moderated by musicologist, Dr. Derek Katz, takes place in the intimacy and comfort of a beautiful Palo Alto homes. We invite you to experience music in a setting that eliminates the boundaries between artist and listener. Together with our “house guests” we share ideas about musical interpretation and inspiration over champagne and appetizers. Spring Salon April 30, 2017, 4 PM Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op. 60 These intimate spaces seat a maximum of 50 guests. Street parking is available. 2 Winter Collective IVES COLLECTIVE Kay Stern, violin; Susan Freier, viola Stephen Harrison, cello; Susan Vollmer, horn Julie Green Gregorian, bassoon; Carlos Ortega, clarinet Arnold Gregorian, string bass; Lori Lack, piano It’s all Beethoven! (1770-1827) Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 16 (1796) Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo String Trio in C minor, Op. 9, No.3 (1798) Allegro con spirito Adagio con espressione Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Finale: Presto Intermission Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1799) Adagio - Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di Menuetto Andante con Variazioni Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con molto Marcia - Presto 3 The Young Beethoven in Vienna and Chamber Music Beethoven left his childhood home of Bonn for Vienna, where he would remain for the rest of his life, in 1792. -

Nicolas Namoradze Honens Prize Laureate Chamber Music / Works for Piano & Voice

NICOLAS NAMORADZE HONENS PRIZE LAUREATE CHAMBER MUSIC / WORKS FOR PIANO & VOICE K. Agócs Immutable Dreams (quintet) Bartók Piano Quintet Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major Op. 12 No. 2 Quintet for Piano and Winds Op. 16 Sonata for Piano and Horn in F Major Op. 17 Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major Op. 24 Sonata for Piano and Cello in A Major Op. 69 Sonata for Piano and Cello in D Major Op. 102 No. 2 Brahms Piano Trio in B Major Op. 8 Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25 selections from Waltzes Op. 39 Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major Op. 78 Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major Op. 99 Piano Trio in C minor Op. 101 Britten Gemini Variations for flute, violin and piano four-hands (Secondo) Cartan Introduction et Allegro for Piano and Wind Quintet Castiglioni Quickly—Variations for Chamber Ensemble Copland Appalachian Spring (chamber version for 13 players) Why do the shut me out of heaven? (voice and piano) Danzon Cubano (Piano I) Rodeo Hoe-Down (Piano I) Debussy Sonata for Piano and Violin L. 140 La Mer (transcription for piano four-hands / Secondo) Jeux (transcription for two pianos: Roques / Primo) Petite Suite (Secondo) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for two pianos / Piano I) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for piano four-hands: Ravel / Secondo) Danses sacrée et profane (transcription for two pianos / Piano II) Dvorak selections from Slavonic Dances Opp. 46 & 72 Dohnányi selections from Ruralia Hungarica Op. -

Ames Piano Quartet Has Been the Ensemble-In- Residence at Iowa State University Since Its Inception in 1976

mind, Fauré finally wrote their names on slips of paper, placed them in a hat, and randomly picked Marie Fremiet, daughter of a sculptor. The first movement of this evening's concluding work launches impetuously EPARTMENT OF USIC HEATRE into a strongly rhythmical but somewhat sad minor key whose theme is D M & T played in unison by the three strings. The following Scherzo has been described as "a buzzing of fairy insects on a moonbeam in a Shakespearean glade" and is full of rhythmic surprises which dramatically contrast with the solemn and wistful melodies of the Adagio. Somewhat reminiscent of a Mazurka in its vigour the Finale builds to an exciting climax to conclude one of the most beloved works of the piano quartet repertoire. Notes by Ralph Aldrich Ames Quartet Biography Ames In various iterations, the Ames Piano Quartet has been the ensemble-in- residence at Iowa State University since its inception in 1976. One of the few regularly constituted piano quartets in the world, the Ames Quartet briefly became the Amara Quartet in 2012, upon the retirement of two of Piano Quartet its long-time members. Wishing to reconnect with more than thirty years of tradition, the Quartet has now returned to its original name of Ames. The Quartet has an extensive discography, including fourteen CDs under the Ames name and a further two as Amara. Labels for which the group has Borivoj Martini -Jer i , violin recorded include Musical Heritage, Dorian, Sono Luminus, Albany, and ć č ć Fleur de Son Classics. “One finds critics writing of their commitment, passion, power, and sensitivity, not to mention their collective technical Stephanie Price-Wong, viola skills,” writes Robert Cummings on the AllMusic.com web site. -

Completing Mahler's Piano Quartet: a Study of Unfinished Music, Ethics

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 5 Completing Mahler’s Piano Quartet: A Study of Unfinished Music, Ethics, and Authenticities Isabella Spinelli Northwestern University Recommended Citation Spinelli, Isabella. “Completing Mahler’s Piano Quartet: A Study of Unfinished Music, Ethics, and Authenticities.” Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology 14, no. 1 (2021): 115-178. https://doi.org/10.5206/notabene.v14i1.13410. Completing Mahler’s Piano Quartet: A Study of Unfinished Music, Ethics, and Authenticities Abstract Performers and scholars have argued for generations over what should be done with musical works that have been left incomplete by their composers. Though many attempts have been made to bring such works to completion, some scholars feel that these fragments should remain untouched because the pieces in question were left incomplete during the composer’s own career. With this debate in mind, I undertook a study and completion of Gustav Mahler’s Piano Quartet in A minor, a piece for which Mahler composed a complete first movement, Nicht zu schnell, and twenty-four bars of a second movement, Scherzo, when he was a student at the Vienna Conservatory. I began by analyzing Nicht zu schnell in order to understand Mahler’s treatment of motives, form, and harmony. In addition, I studied contemporary works by Schumann and Brahms. Based on my analyses, I then composed a completion of the Scherzo in a style that is, in my opinion, idiomatic of Mahler. After a performance of my completion, seventy percent of the audience responded with five on a scale of zero to six when asked in a survey how closely my Scherzo aligned with Nicht zu schnell. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

SCMS Repertoire List Through 2021 Winter Festival

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY REPERTOIRE LIST, 1982–2021 “FORTY YEARS OF BEAUTIFUL MUSIC” James Ehnes, Artistic Director Toby Saks (1942-2013), Founder Adams, John China Gates for Piano (2013) Arensky, Anton Hallelujah Junction for Two Pianos (2012, 2017W) Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 51 (1997, 2003, 2011W) Road Movies for Violin and Piano (2013) Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 32 (1984, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2001, 2007, 2010O, 2016W) Aho, Kalevi Piano Trio in F minor, Op. 73 (2001W, 2009) ER-OS (2018) Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Celli in A minor, Op. 35 (1989, 1995, 2008, 2011) Albéniz, Isaac Six Piéces for Piano, Op. 53 (2013) Iberia (3 selections from) (2003) Iberia “Evocation” (2015) Arlen, Harold Wizard of Oz Fantasy (arr. William Hirtz) (2002) Alexandrov, Kristian Prayer for Trumpet and Piano (2013) Arnold, Malcolm Sonatina for Oboe and Piano, Op. 28 (2004) Applebaum "Landscape of Dreams" (1990) Babajanian, Arno Piano Trio in F sharp minor (2015) Andres, Bernard Narthex for Flute and Harp (2000W) Bach, Johann Sebastian “Aus liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 Anderson, David (for flute, arr. Bennett) (2019) Capriccio No. 2 for Solo Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concerto No 3 in G major, BWV 1048 (2011) Four Short Pieces for Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concertos (Complete) BWV 1046-1051 (2013W) Capriccio “On the Departure of a Beloved Brother” in B flat major, BWV 992 Anderson, Jordan (2006) Drafts for Double Bass and Piano (2006) Chaconne, from Partita for Violin in D minor, BWV 1004 (1994, 2001, 2002) Choral Preludes for Organ (Piano) (Selections) (1998) Anonymous (arr. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program by James m. keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter may Chair Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 15 Gabriel Fauré abriel Fauré’s Piano Quartet No. 1 falls Nothing, in my opinion, warrants docile Gearly in the composer’s catalogue of acceptance of such a sentimental and im - chamber music, and he followed up on its prudent thesis. Fauré’s reserve always pre - success by composing the G-minor Piano vented him from following the example of Quartet several years later. He would not re - Romantic artists who allowed the whole turn to that instrumental combination again, world to witness their personal frustra - though in his later chamber production he tions … . Capable of enlarging his style to produced two piano quintets and, at the very treat a pathetic theme possessing some - end of his life, a piano trio and a string quar - thing universal, Fauré would never have tet. This earliest of his piano quartets under - consented to express himself in such a went a lengthy gestation, perhaps slowed spectacular manner. down by a degree of turmoil in the com - poser’s personal life. During the 1870s Fauré Indeed, “spectacular” is never a word ap - was a regular attendee at the salon of the propriate to Fauré’s music, although the famous mezzo-soprano and composer opening of the First Piano Quartet at least Pauline Viardot, and in the course of his visits qualifies as forcefully dramatic, with the there he fell in love with her daughter, Mari - three string instruments announcing the anne. -

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center with Daniel

SAVANNAH MUSIC FESTIVAL 30TH FESTIVAL SEASON MARCH 28–APRIL 13, 2019 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER WITH DANIEL HOPE Sunday, March 31 at 5 pm Quartet in A minor, Opus 1 (1891) Trinity United Methodist Church break, Dvořák assigned them to write a set of Josef Suk was born in Křečovice, Bohemia, variations on a theme he proposed but, realizing on January 4, 1874, and died in Benešov, near a greater potential in Suk, told him that he JOSEF SUK (1874–1935) Quartet in A minor, Opus 1 (1891) Prague, on May 29, 1935. Premiered on May 13, wanted something more substantial from him I. Allegro appassionato 1891, in Prague. for piano quartet. Suk spent his time at home in II. Adagio Approximate performance time is 22 minutes. Křečovice, in the country 40 miles south of the III. Allegro con fuoco SMF performance history: SMF premiere capital, completing the first movement of his JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–1897) Quartet in A minor, but he could only finish the Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Opus 60 (1855- Josef Suk, one of the most prominent musical first two sections of the Adagio before heading 56, 1874) personalities of the early 20th century, was back to school. When Suk played on the piano I. Allegro non troppo born into a musical family and entered the what he had written for his teacher, Dvořák II. Scherzo. Allegro Prague Conservatory at the age of 11 to study walked over to him, kissed him on the forehead, III. -

STYLISTIC CHARACTERISTICS of GABRIEL FAURE's PIANO QUARTETS and PIANO QUINTETS

STYLISTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF GABRIEL FAURE's PIANO QUARTETS AND PIANO QUINTETS A minor dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Music This material has not previously been submitted for a degree at this or any other university Veranza 'W'interbach WNTSUS003 Supervisor: Associate Professor Hendrik Hofmeyr Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2003 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town DECLARATION This workhas not beenpreviously submitted in whole, or in part, forthe award of anydegree. lt is my own work. Each significantcontribution to, and quotation in, thls dissertation fromthe work or worksof other people has been attributed, and hasbeen cited andreferenced. Signature Removed 2/12/2003 Signature Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement of Professor Hendrik Hofmeyr and his generosity in sharing his valuable time and knowledge with me. Professor Hofrneyr's thesis contributed greatly to my insight. I also appreciate his understanding of Faure's unique integration of modality and tonality, and his enth~iasm for and interest in Faure's work. INTRODUCTION Gabriel Faure has been neglected as composer in tenns of international recognition. It is indeed true that the art of his music is not revealed at first sight: one must take time to discover the beauty and authentic meaning concealed in the depths thereof.