Completing Mahler's Piano Quartet: a Study of Unfinished Music, Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

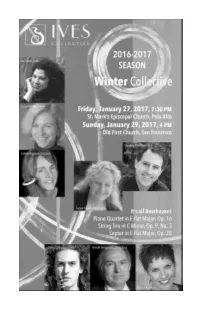

Ives 2017 Winter Program Book

IVES COLLECTIVE Season 2 Spring Collective Roy Malan, violin; Roberta Freier, violin Susan Freier, viola; Stephen Harrison, cello Elizabeth Schumann, piano Susanne Mentzer, mezzo soprano Friday,Please May 5,save 2017, these7:30 PM dates! St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Palo Alto Sunday, May 7, 2016, 4PM Old First Church, San Francisco Ottorino Respighi: Il Tramonto Johannes Brahms: Songs for Voice, Viola and Piano, Op. 91 Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60 Salon Concert Our Salon series, moderated by musicologist, Dr. Derek Katz, takes place in the intimacy and comfort of a beautiful Palo Alto homes. We invite you to experience music in a setting that eliminates the boundaries between artist and listener. Together with our “house guests” we share ideas about musical interpretation and inspiration over champagne and appetizers. Spring Salon April 30, 2017, 4 PM Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op. 60 These intimate spaces seat a maximum of 50 guests. Street parking is available. 2 Winter Collective IVES COLLECTIVE Kay Stern, violin; Susan Freier, viola Stephen Harrison, cello; Susan Vollmer, horn Julie Green Gregorian, bassoon; Carlos Ortega, clarinet Arnold Gregorian, string bass; Lori Lack, piano It’s all Beethoven! (1770-1827) Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 16 (1796) Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo String Trio in C minor, Op. 9, No.3 (1798) Allegro con spirito Adagio con espressione Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Finale: Presto Intermission Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1799) Adagio - Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di Menuetto Andante con Variazioni Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con molto Marcia - Presto 3 The Young Beethoven in Vienna and Chamber Music Beethoven left his childhood home of Bonn for Vienna, where he would remain for the rest of his life, in 1792. -

Nicolas Namoradze Honens Prize Laureate Chamber Music / Works for Piano & Voice

NICOLAS NAMORADZE HONENS PRIZE LAUREATE CHAMBER MUSIC / WORKS FOR PIANO & VOICE K. Agócs Immutable Dreams (quintet) Bartók Piano Quintet Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major Op. 12 No. 2 Quintet for Piano and Winds Op. 16 Sonata for Piano and Horn in F Major Op. 17 Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major Op. 24 Sonata for Piano and Cello in A Major Op. 69 Sonata for Piano and Cello in D Major Op. 102 No. 2 Brahms Piano Trio in B Major Op. 8 Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25 selections from Waltzes Op. 39 Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major Op. 78 Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major Op. 99 Piano Trio in C minor Op. 101 Britten Gemini Variations for flute, violin and piano four-hands (Secondo) Cartan Introduction et Allegro for Piano and Wind Quintet Castiglioni Quickly—Variations for Chamber Ensemble Copland Appalachian Spring (chamber version for 13 players) Why do the shut me out of heaven? (voice and piano) Danzon Cubano (Piano I) Rodeo Hoe-Down (Piano I) Debussy Sonata for Piano and Violin L. 140 La Mer (transcription for piano four-hands / Secondo) Jeux (transcription for two pianos: Roques / Primo) Petite Suite (Secondo) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for two pianos / Piano I) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for piano four-hands: Ravel / Secondo) Danses sacrée et profane (transcription for two pianos / Piano II) Dvorak selections from Slavonic Dances Opp. 46 & 72 Dohnányi selections from Ruralia Hungarica Op. -

Ames Piano Quartet Has Been the Ensemble-In- Residence at Iowa State University Since Its Inception in 1976

mind, Fauré finally wrote their names on slips of paper, placed them in a hat, and randomly picked Marie Fremiet, daughter of a sculptor. The first movement of this evening's concluding work launches impetuously EPARTMENT OF USIC HEATRE into a strongly rhythmical but somewhat sad minor key whose theme is D M & T played in unison by the three strings. The following Scherzo has been described as "a buzzing of fairy insects on a moonbeam in a Shakespearean glade" and is full of rhythmic surprises which dramatically contrast with the solemn and wistful melodies of the Adagio. Somewhat reminiscent of a Mazurka in its vigour the Finale builds to an exciting climax to conclude one of the most beloved works of the piano quartet repertoire. Notes by Ralph Aldrich Ames Quartet Biography Ames In various iterations, the Ames Piano Quartet has been the ensemble-in- residence at Iowa State University since its inception in 1976. One of the few regularly constituted piano quartets in the world, the Ames Quartet briefly became the Amara Quartet in 2012, upon the retirement of two of Piano Quartet its long-time members. Wishing to reconnect with more than thirty years of tradition, the Quartet has now returned to its original name of Ames. The Quartet has an extensive discography, including fourteen CDs under the Ames name and a further two as Amara. Labels for which the group has Borivoj Martini -Jer i , violin recorded include Musical Heritage, Dorian, Sono Luminus, Albany, and ć č ć Fleur de Son Classics. “One finds critics writing of their commitment, passion, power, and sensitivity, not to mention their collective technical Stephanie Price-Wong, viola skills,” writes Robert Cummings on the AllMusic.com web site. -

Camera Lucida Symphony, Among Others

Pianist REIKO UCHIDA enjoys an active career as a soloist and chamber musician. She performs Taiwanese-American violist CHE-YEN CHEN is the newly appointed Professor of Viola at regularly throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe, in venues including Suntory Hall, the University of California, Los Angeles Herb Alpert School of Music. He is a founding Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, the 92nd Street Y, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, member of the Formosa Quartet, recipient of the First-Prize and Amadeus Prize winner the Kennedy Center, and the White House. First prize winner of the Joanna Hodges Piano of the 10th London International String Quartet Competition. Since winning First-Prize Competition and Zinetti International Competition, she has appeared as a soloist with the in the 2003 Primrose Competition and “President Prize” in the Lionel Tertis Competition, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Santa Fe Symphony, Greenwich Symphony, and the Princeton Chen has been described by San Diego Union Tribune as an artist whose “most impressive camera lucida Symphony, among others. She made her New York solo debut in 2001 at Weill Hall under the aspect of his playing was his ability to find not just the subtle emotion, but the humanity Sam B. Ersan, Founding Sponsor auspices of the Abby Whiteside Foundation. As a chamber musician she has performed at the hidden in the music.” Having served as the principal violist of the San Diego Symphony for Chamber Music Concerts at UC San Diego Marlboro, Santa Fe, Tanglewood, and Spoleto Music Festivals; as guest artist with Camera eight seasons, he is the principal violist of the Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra, and has Lucida, American Chamber Players, and the Borromeo, Talich, Daedalus, St. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

Dvorak String Quartet Op 87

Antonín Dvo!ák (1841-1904) Piano Quartet no. 2 in E flat major, op. 87 (1889) Allegro con fuoco Lento Allegro moderato, grazioso Finale. Allegro ma non troppo The second piano quartet was written in Dvo!ák's maturity. Encouraged by Brahms, he had achieved early success with the Czech folk-based Slavonic Dances, but he later had to develop a more serious Germanic style to please his Viennese audiences. They had become biased against Czech-flavoured music by the rising tide of Czech nationalism. However, throughout the 1880s, on his frequent visits to England, Dvo!ák had enjoyed unstinting admiration. English concert-goers showed none of the anti-Czech prejudice of the Viennese. Encouraged by this success, the cheerful good humour of this second piano quartet (and of the Eighth Symphony, which was written immediately after it) returns to the Czech idiom, but with its structure strengthened by Dvo!ák's enforced Germanic digression. The work was requested by his publisher Simrock to whom Dvo!ák wrote enthusiastically on August 10, 1889: "I've now already finished three movements of a new piano quartet and the Finale will be ready in a few days. As I expected it came easily and the melodies just surged upon me. Thank God!" Curiously, the first bar of the main theme of the first movement could have been the inspiration for the previous Kodály Duo (and indeed for Queen's Radio Ga Ga) with its rising second and falling fourth. After showing us some of the interest of this boldly energetic theme, Dvo!ák slides into the unexpected key of G major and the viola introduces the lyrical second subject. -

SCMS Repertoire List Through 2021 Winter Festival

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY REPERTOIRE LIST, 1982–2021 “FORTY YEARS OF BEAUTIFUL MUSIC” James Ehnes, Artistic Director Toby Saks (1942-2013), Founder Adams, John China Gates for Piano (2013) Arensky, Anton Hallelujah Junction for Two Pianos (2012, 2017W) Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 51 (1997, 2003, 2011W) Road Movies for Violin and Piano (2013) Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 32 (1984, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2001, 2007, 2010O, 2016W) Aho, Kalevi Piano Trio in F minor, Op. 73 (2001W, 2009) ER-OS (2018) Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Celli in A minor, Op. 35 (1989, 1995, 2008, 2011) Albéniz, Isaac Six Piéces for Piano, Op. 53 (2013) Iberia (3 selections from) (2003) Iberia “Evocation” (2015) Arlen, Harold Wizard of Oz Fantasy (arr. William Hirtz) (2002) Alexandrov, Kristian Prayer for Trumpet and Piano (2013) Arnold, Malcolm Sonatina for Oboe and Piano, Op. 28 (2004) Applebaum "Landscape of Dreams" (1990) Babajanian, Arno Piano Trio in F sharp minor (2015) Andres, Bernard Narthex for Flute and Harp (2000W) Bach, Johann Sebastian “Aus liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 Anderson, David (for flute, arr. Bennett) (2019) Capriccio No. 2 for Solo Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concerto No 3 in G major, BWV 1048 (2011) Four Short Pieces for Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concertos (Complete) BWV 1046-1051 (2013W) Capriccio “On the Departure of a Beloved Brother” in B flat major, BWV 992 Anderson, Jordan (2006) Drafts for Double Bass and Piano (2006) Chaconne, from Partita for Violin in D minor, BWV 1004 (1994, 2001, 2002) Choral Preludes for Organ (Piano) (Selections) (1998) Anonymous (arr. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program by James m. keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter may Chair Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 15 Gabriel Fauré abriel Fauré’s Piano Quartet No. 1 falls Nothing, in my opinion, warrants docile Gearly in the composer’s catalogue of acceptance of such a sentimental and im - chamber music, and he followed up on its prudent thesis. Fauré’s reserve always pre - success by composing the G-minor Piano vented him from following the example of Quartet several years later. He would not re - Romantic artists who allowed the whole turn to that instrumental combination again, world to witness their personal frustra - though in his later chamber production he tions … . Capable of enlarging his style to produced two piano quintets and, at the very treat a pathetic theme possessing some - end of his life, a piano trio and a string quar - thing universal, Fauré would never have tet. This earliest of his piano quartets under - consented to express himself in such a went a lengthy gestation, perhaps slowed spectacular manner. down by a degree of turmoil in the com - poser’s personal life. During the 1870s Fauré Indeed, “spectacular” is never a word ap - was a regular attendee at the salon of the propriate to Fauré’s music, although the famous mezzo-soprano and composer opening of the First Piano Quartet at least Pauline Viardot, and in the course of his visits qualifies as forcefully dramatic, with the there he fell in love with her daughter, Mari - three string instruments announcing the anne.