STYLISTIC CHARACTERISTICS of GABRIEL FAURE's PIANO QUARTETS and PIANO QUINTETS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten Yhtenäistettyjen Nimekkeiden Ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 108 Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys ry Ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila. – Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjas- toyhdistys, 2012. – 19 s. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 108) – ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 2 Luettelon käyttäjälle GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924) ei ole kirjastodokumentoinnin näkökulmasta erityisen hankala sävel- täjä. Useiden sävellysten pysyvä suosio antaa kuitenkin aihetta koko tuotannon standardointiin. Varsinaista teosluetteloa ei ole olemassa, vaan tiedot pohjautuvat keskeisissä hakuteoksissa oleviin luetteloihin. Pääosa Faurén sävellyksistä on opusnumeroituja, numerottomia on vain muutama kymmenen, nekin pääosin vähemmän tunnettuja teoksia. Opusnumerolistassa näyttäisi puuttuvan muutamia numeroita (9, 53, 60, 64, 71, 81, 100), joita ei ole ainakaan toistaiseksi löytynyt. Helsingin Viikissä lokakuussa 2012 Heikki Poroila Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 3 Opusnumeroidut teokset [Le papillon et la fleur, op1, nro 1] ► 1861. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ La pauvre fleur disait au papillon céleste [Mai, op1, nro 2] ► 1862. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Puis-que Mai tout en fleurs dans les prés nous réclame [Dans les ruines d’une abbaye, op2, nro 1] ► 1866. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Seuls, tous deux, ravis, chantants,comme on s’aime [Les matelots, op2, nro 2] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Sur l’eau bleue et profonde [Seule!, op3, nro 1] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Dans un baiser, l’onde au ravage dit ses douleurs [Sérénade toscane, op3, nro 2] ► 1878. -

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Audition Literature Information

Audition Literature Information This compilation has been prepared by the music faculty to indicate expectations (not requirements) in music literature. Students are encouraged to perform selections that will display their best performing ability. They may elect to perform equivalent music that does not appear on the list. Audition literature selections must include two works of contrasting style. The selections may come from a single, larger work such as two movements from a Baroque sonata Instrument Audition literature should be similar in difficulty to… Voice Songs in Books I-II of LaForge, Pathways of Song; Ward, The Singing Road; Patton, 26 Italian Songs and Arias Piano Bach Inventions; Schumann Album for the Young; Chopin Preludes; Bartok, Ten Easy Pieces or Mikrokosmos, Vol. III Organ Bach, Eight Little Preludes and Fugues; or piano proficiency equal to perform Bach inventions or Clementi sonatinas Strings Violin Kreutzer, 42 studies; Vivaldi, Concerto in A Minor or Concerto in G minor; Bach, Concerto in A Minor; any of the Handel Sonatas Viola Wolhfahrt, Foundation Studies (Bk. 1): 20 Studies from Op. 45; Klengel, Klassiche Stücke, Vols. 1 & 3; Marcello, Sonata in G; Fauré, Sicilienne Cello Marcello, Sonata in E or Sonata in A; Golterman, Concerto No. 4 in G; Vivaldi, Six Sonatas Bass Marcello, Vivaldi or similar contrasting movements of a Baroque Sonata; Capuzzi, 1st movement of Concerto in F (or D major); Zimmerman, Solos For The Double Bass Player. Guitar Noad, Solo Guitar Playing-Book One; Sor, 20 Studies; Any selection by -

Requiem, Op. 48 Gabriel Fauré (1845 - 1924)

ASO Program Notes Requiem, Op. 48 Gabriel Fauré (1845 - 1924) Gabriel Fauré grew up in the French Pyrenees and began his musical education at a very early age. He studied organ, piano and choral music at increasingly more prestigious schools, ending up at the Niedermeyer School in Paris. His teachers included Camille Saint-Saëns. When he later became a teacher at the Paris Conservatory, Maurice Ravel and Nadia Boulanger were among his pupils. He served as organist and choirmaster at a number of large churches in Paris, and enjoyed an excellent reputation as a successful composer until he grew deaf and had to give up much of his musical life. There have been many famous Requiems, and all have their own style. Verdi, Berlioz, and Brahms all composed glorious Requiems addressing the themes of death, resurrection and final judgment. The tone of their works is grand and even theatrical. Mozart’s Requiem is moving and poignant. Fauré chose to make his gentler, full of solace and comfort for the mourners. It is also moving, but in a kinder, more consoling way. The awesome vision of “The Last Judgement” would have meant little to Fauré. In spite of the fact that most of his life had been dedicated to service to the church, he was an unbeliever, and so he focused more on the blessed rest for those whose life journey had come to an end. In Fauré’s words, “Everything I managed to entertain in the way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which is…dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest.” and at another time, “I see death as a happy deliverance, an aspiration towards happiness above, rather than as a painful experience.” Although firmly agnostic, he was a spiritual man, and sought to compose a newer kind of church music, different from the heavily romantic style of the German composers dominating European music at the time. -

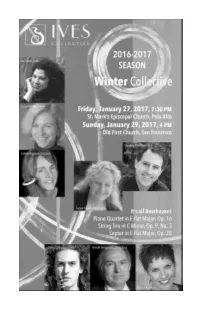

Ives 2017 Winter Program Book

IVES COLLECTIVE Season 2 Spring Collective Roy Malan, violin; Roberta Freier, violin Susan Freier, viola; Stephen Harrison, cello Elizabeth Schumann, piano Susanne Mentzer, mezzo soprano Friday,Please May 5,save 2017, these7:30 PM dates! St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Palo Alto Sunday, May 7, 2016, 4PM Old First Church, San Francisco Ottorino Respighi: Il Tramonto Johannes Brahms: Songs for Voice, Viola and Piano, Op. 91 Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60 Salon Concert Our Salon series, moderated by musicologist, Dr. Derek Katz, takes place in the intimacy and comfort of a beautiful Palo Alto homes. We invite you to experience music in a setting that eliminates the boundaries between artist and listener. Together with our “house guests” we share ideas about musical interpretation and inspiration over champagne and appetizers. Spring Salon April 30, 2017, 4 PM Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op. 60 These intimate spaces seat a maximum of 50 guests. Street parking is available. 2 Winter Collective IVES COLLECTIVE Kay Stern, violin; Susan Freier, viola Stephen Harrison, cello; Susan Vollmer, horn Julie Green Gregorian, bassoon; Carlos Ortega, clarinet Arnold Gregorian, string bass; Lori Lack, piano It’s all Beethoven! (1770-1827) Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 16 (1796) Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo String Trio in C minor, Op. 9, No.3 (1798) Allegro con spirito Adagio con espressione Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Finale: Presto Intermission Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1799) Adagio - Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di Menuetto Andante con Variazioni Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con molto Marcia - Presto 3 The Young Beethoven in Vienna and Chamber Music Beethoven left his childhood home of Bonn for Vienna, where he would remain for the rest of his life, in 1792. -

Masques Et Bergamasques – Suite, Op 112 Ouverture Menuet Gavotte Pastorale

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Masques et Bergamasques – Suite, Op 112 Ouverture Menuet Gavotte Pastorale Fauré is not usually thought of as a composer for the theatre. Indeed, there is a cartoon showing him literally weaving the score of his opera Pénélope (1913) – it took him so long to finish, in the time left over from his duties as director of the Paris Conservatoire, that he seemed to be adopting his heroine’s ruse. In fact, Fauré’s numerous plans for a full-scale lyric drama foundered on his inability to find a suitable libretto – like most French composers, he longed for a success in the theatre. He appeased this ‘lyric hunger’, as he explained in a letter to his friend Saint-Saëns, in incidental music for plays, ‘the only kind which suits my modest means’. His scores for plays include Caligula (1888), Shylock (1889) and Pelleas and Melisande, for a London production in 1898. The opera Pénélope was premiered in Monte Carlo; shortly after World War I ended, Fauré received a commission from the Prince of Monaco for the same theatre. Fauré’s idea was to take up again the Fête galante theme he had already explored in several songs and choruses. In 1902 an entertainment of this sort using his music had been a great success in the Paris salon of Madeleine Lemaire. Fauré asked the librettist of Pénélope, René Fauchois, to write a lightweight, playful piece in the style of Verlaine’s Fêtes galantes. Fauchois’ own description of the scenario makes clear that it was little more than a pretext: Harlequin, Gilles and Columbine, the masques who often amused the court, in turn amuse themselves at being the spectators of a fête galante at Cythera; without knowing it, the gentlemen and ladies who applaud them give them the impromptu play of their petty coquetteries and their trivial talk. -

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Faure Requiem Program V2

FAURÉ REQUIEM Conceived and directed by Barbara Pickhardt, Artistic Director Produced by Barbara Scharf Schamest Premiered: June 13, 2021 Ars Choralis Barbara Pickhardt, artistic director REQUIEM, Op. 48 (1893) Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Introit Brussels Choral Society Eric Delson, conductor Kyrie Ars Choralis Chamber Orchestra Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Offertory Ars Choralis Chuck Snyder, baritone Eribeth Chamber Players Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Sanctus The Dessoff Choirs Malcolm J. Merriweather, conductor Pie Jesu (Remembrances) Magna Graecia Flute Choir Carlo Verio Sirignano, guest conductor Sebastiano Valentino, music director Agnus Dei Ars Choralis Magna Graecia Flute Choir Carlo Verio Sirignano, guest conductor Chamber Orchestra Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Libera Me Ars Choralis Harvey Boyer, tenor Douglas Kostner, organ Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Memorial Prayers Tatjana Myoko Evan Pritchard Rabbi Jonathan Kligler Elizabeth Lesser Pastor Sonja Tillberg Maclary In Paradisum Brussels Choral Society Eric Delson, conductor 1 Encore Performances Pie Jesu Ars Choralis Amy Martin, soprano Eribeth Chamber Playersr Barbara Pickhardt, conductor In Paradisum The Dessoff Choirs Malcolm J. Merriweather, conductor About This Virtual Concert By Barbara Pickhardt The Fauré Requiem Reimagined for a Pandemic This virtual performance of the Fauré Requiem grew out of the need to prepare a concert while maintaining social distancing. We would surely have preferred to blend our voices as we always have, in a live performance. But the pandemic opened the door to a new and different opportunity. As we saw the coronavirus wreak havoc around the world, it seemed natural to reach out to our friends in other locales and include them in this program. In our reimagined version of the Fauré Requiem, Ars Choralis is joined, from Belgium, by the Brussels Choral Society, the Magna Graecia Flute Choir of Calabria, Italy, the Dessoff Choirs from New York City, and, from New York, instrumentalists from the Albany area, New York City and the Hudson Valley. -

Ethereal Light Program Notes

Ethereal Light – Program Notes Ethereal: adj. very light or airy, belonging to the heavens, otherworldly Light: n. energy that makes seeing possible, the representation of light or the effect it has in a work of art, God as a source of spiritual illumination This afternoon’s program features music of the great French composer Gabriel Fauré, as well as a singular work each from the celebrated Sergei Rachmaninoff and the contemporary genius of Morten Lauridsen. Composed during a span of over one hundred years, these divergent works are drawn together by the subject of Light. In Fauré’s Requiem, the familiar text from the Catholic Mass for the Dead speaks directly of “eternal light” and “perpetual light,” invoked to “shine forever” on those who have died. They are asked to be saved from “utter darkness” and the “darkness of hell,” perhaps implying that the unmistakable quality of heaven is Light itself. In the same composer’s Après un Rêve, the singer wishes to return to the “awakening light” of his dream, now sadly over. In Lauridsen’s masterwork, Lux Aeterna (Light Eternal), each of the five movements reference Light in their own way, the opening and closing movements not dissimilarly to the Requiem of Fauré. The texts of the inner three movements, all drawn from sacred Latin sources, contain their own unique references to Light, including one of the most celebrative moments in the work which uses the words, “O Lux beatissima” (O Light most blessed). It is in the hearing of today’s two works without text – Pavane and Vocalise – in which perhaps the ear of the listener is most responsible for providing the connection to the theme of Light. -

Berlioz Requiem Alto Road

BERLIOZ: Grand Messe des Morts Alto Road Map I. Requiem and Kyrie (Introit) •First entrance at rehearsal B: sing tenor I part, stop singing at 7 measures after rehearsal C. •Re-enter at 13 measures after rehearsal C: sing soprano (II) part here. •Switch to tenor part at 6 measures after rehearsal E. •Switch to soprano II part 5 measures after rehearsal F. •Sing tenor part 10th-14th measures after rehearsal F. •Switch back to soprano II 4 measures before rehearsal G. •Sing soprano II part until end of movement, II. Dies irae •First entrance: sing tenor part 5 measures after rehearsal B. •Switch to soprano II 5 measures after rehearsal C. •Hum tenor part 4 measures before rehearsal D •Stay humming tenor part until 9 measures before rehearsal E—switch to soprano II here. •Switch to tenor I part at 17 measures after rehearsal F. •Do not sing at 9 measures before rehearsal K. •Re-enter on tenor I part 7 measures after rehearsal L •Tacet from 3 measures before rehearsal M to 4 measures before rehearsal P. •Re-enter at 4 measures before rehearsal P on soprano part. •Switch to tenor I at rehearsal Q. •Switch to soprano II at rehearsal R to end of movement. III. Quid sum miser •Hum tenor I line at throughout, IV. Rex tremendae •Begin with soprano II part. •Tacet from rehearsal B to rehearsal C. •Re-enter at rehearsal C with soprano II part. •Remain on sropano II part except sing tenor I for the four measures before rehearsal E. •Return to soprano II from rehearsal E to 6 measures after rehearsal E, •Switch to tenor I at 7 measures after rehearsal E. -

Nicolas Namoradze Honens Prize Laureate Chamber Music / Works for Piano & Voice

NICOLAS NAMORADZE HONENS PRIZE LAUREATE CHAMBER MUSIC / WORKS FOR PIANO & VOICE K. Agócs Immutable Dreams (quintet) Bartók Piano Quintet Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major Op. 12 No. 2 Quintet for Piano and Winds Op. 16 Sonata for Piano and Horn in F Major Op. 17 Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major Op. 24 Sonata for Piano and Cello in A Major Op. 69 Sonata for Piano and Cello in D Major Op. 102 No. 2 Brahms Piano Trio in B Major Op. 8 Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25 selections from Waltzes Op. 39 Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major Op. 78 Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major Op. 99 Piano Trio in C minor Op. 101 Britten Gemini Variations for flute, violin and piano four-hands (Secondo) Cartan Introduction et Allegro for Piano and Wind Quintet Castiglioni Quickly—Variations for Chamber Ensemble Copland Appalachian Spring (chamber version for 13 players) Why do the shut me out of heaven? (voice and piano) Danzon Cubano (Piano I) Rodeo Hoe-Down (Piano I) Debussy Sonata for Piano and Violin L. 140 La Mer (transcription for piano four-hands / Secondo) Jeux (transcription for two pianos: Roques / Primo) Petite Suite (Secondo) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for two pianos / Piano I) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for piano four-hands: Ravel / Secondo) Danses sacrée et profane (transcription for two pianos / Piano II) Dvorak selections from Slavonic Dances Opp. 46 & 72 Dohnányi selections from Ruralia Hungarica Op.