Influences in Ernest Chausson's Piano Quartet Ching-Yueh Chen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

The Third Period of César Franck Author(S): Sydney Grew Source: the Musical Times, Vol

The Third Period of César Franck Author(s): Sydney Grew Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 60, No. 919 (Sep. 1, 1919), pp. 462-464 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3701958 Accessed: 25-03-2015 19:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 462 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-SEPTEMBER I, 1919. He is content to spend days on a single passage I wasnot sorrowful. (Boosey.) The Cost. 2. The so that he gives it the one ultimate formwhich (I. Blind; Cost.) (WinthropRogers.) afterwards to be the inevitable form it The Soldier. (WinthropRogers.) proves Blowout, you bugles. (WinthropRogers.) should take. Yet this constant preoccupation The Heart'sDesire. (WinthropRogers.) with precision in detail has nowhere resulted in Earth's Call. (Rhapsodyfor voice and pianoforte.) laboured writing. His harmonic texture may be (WinthropRogers.) or suave or SpringSorrow. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

Ives 2017 Winter Program Book

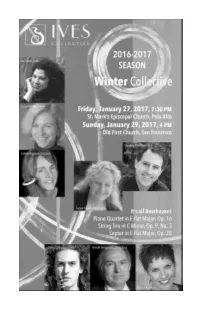

IVES COLLECTIVE Season 2 Spring Collective Roy Malan, violin; Roberta Freier, violin Susan Freier, viola; Stephen Harrison, cello Elizabeth Schumann, piano Susanne Mentzer, mezzo soprano Friday,Please May 5,save 2017, these7:30 PM dates! St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Palo Alto Sunday, May 7, 2016, 4PM Old First Church, San Francisco Ottorino Respighi: Il Tramonto Johannes Brahms: Songs for Voice, Viola and Piano, Op. 91 Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60 Salon Concert Our Salon series, moderated by musicologist, Dr. Derek Katz, takes place in the intimacy and comfort of a beautiful Palo Alto homes. We invite you to experience music in a setting that eliminates the boundaries between artist and listener. Together with our “house guests” we share ideas about musical interpretation and inspiration over champagne and appetizers. Spring Salon April 30, 2017, 4 PM Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op. 60 These intimate spaces seat a maximum of 50 guests. Street parking is available. 2 Winter Collective IVES COLLECTIVE Kay Stern, violin; Susan Freier, viola Stephen Harrison, cello; Susan Vollmer, horn Julie Green Gregorian, bassoon; Carlos Ortega, clarinet Arnold Gregorian, string bass; Lori Lack, piano It’s all Beethoven! (1770-1827) Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 16 (1796) Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo String Trio in C minor, Op. 9, No.3 (1798) Allegro con spirito Adagio con espressione Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Finale: Presto Intermission Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1799) Adagio - Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di Menuetto Andante con Variazioni Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con molto Marcia - Presto 3 The Young Beethoven in Vienna and Chamber Music Beethoven left his childhood home of Bonn for Vienna, where he would remain for the rest of his life, in 1792. -

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater FAIRWINDS GROWS MY MONEY SO I CAN GROW MY BUSINESS. Get the freedom to go further. Insured by NCUA. OPERA-2646-02/092719 Opera Orlando’s Carmen On the MainStage at Dr. Phillips Center | April 2021 Dear friends, Carmen is finally here! Although many plans have changed over the course of the past year, we have always had our sights set on Carmen, not just because of its incredible music and compelling story but more because of the unique setting and concept of this production in particular - 1960s Haiti. So why transport Carmen and her friends from 1820s Seville to 1960s Haiti? Well, it all just seemed to make sense, for Orando, that is. We have a vibrant and growing Haitian-American community in Central Florida, and Creole is actually the third most commonly spoken language in the state of Florida. Given that Creole derives from French, and given the African- Carribean influences already present in Carmen, setting Carmen in Haiti was a natural fit and a great way for us to celebrate Haitian culture and influence in our own community. We were excited to partner with the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce for this production and connect with Haitian-American artists, choreographers, and academics. Since Carmen is a tale of survival against all odds, we wanted to find a particularly tumultuous time in Haiti’s history to make things extra difficult for our heroine, and setting the work in the 1960s under the despotic rule of Francois Duvalier (aka Papa Doc) certainly raised the stakes. -

Susan Merdinger Repertoire List 07.01.19 Copy.Pages

SUSAN MERDINGER, Pianist and Conductor: Repertoire (2019) CONCERTOS and WORKS for PIANO(S) and ORCHESTRA: AS SOLOIST. (Additional concerti available upon request.** indicates performed with within last 5 years) Albeniz: Rapsodia Espanola, Op. 70 (Two Pianos) ** Anderson: Piano Concerto in C major Bach-Vivaldi: Concerto for Four Pianos and String Orchestra (Piano 1)** Beethoven: All Five Concerti- Op. 15, Op.19, Op.37, Op. 73 (The “Emperor”) Triple Concerto for Piano, Violin, and Cello ** Bloch: Concerto Grosso for Piano and Strings ** Brahms: No.1 in d minor, Op. 15 No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83** Franck: Symphonic Variations** Lutoslawski: Variations on a Theme by Paganini Mozart: K.365 (Two Pianos)**, A major K. 414, G major K. 453, D minor K. 466, C major K.467**, A major K.488, C major K.503** Mendelssohn: Concerto No. 1 in g minor Concerto No. 2 in d minor Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue ** Gottschalk: L’Union**, Grande Tarantella ** Rachmaninoff: Concerto No. 2 in c minor Rhapsody on Theme of Paganini Schumann: Concerto in a, Op.54 ** Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals (Two Pianos) ** Saint-Saëns: Concerto No. 2 in g minor Tchaikovsky: No.1 in B-flat minor, Op.23 ** Liszt: No. 1 in E-flat ** Poulenc: Concerto for Two Pianos ** SOLO PIANO: SELECTED WORKS PERFORMED LIVE: (Bolded works are available on CD recording- many works available in live video format on YouTube) Aaron Alter: Piano Sonata (2012-2018) dedicated to Susan Merdinger (USA premieres in November 2018) Albéniz: Suite Española, Op. 47 J.S. Bach: French Suite No. -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION Patron Her Majesty The Queen President Sir John Tomlinson CBE Principal Professor Linda Merrick Chairman Nick Prettejohn To enhance everyone’s experience of this event please try to stifle coughs and sneezes, avoid unwrapping sweets during the performance and switch off mobile phones, pagers and digital alarms. Please do not take photographs or video in 0161 907 5555 X the venue. Latecomers will not be admitted until a suitable break in the 1 2 3 4 5 6 programme, or at the first interval, whichever is the more appropriate. 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > The RNCM reserves the right to change artists and/or programmes as necessary. The RNCM reserves the right of admission. 0161 907 5555 X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > Welcome It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration, marking the 100th anniversary of the death of Claude Debussy on 25 March 1918. Divided into two conferences, ‘Debussy Perspectives’ at the RNCM and ‘Debussy’s Late work and the Musical Worlds of Wartime Paris’ at the University of Glasgow, this significant five-day event brings together world experts and emerging scholars to reflect critically on the current state of Debussy research of all kinds. With guest speakers from 13 countries, including Brazil, China and the USA, we explore Debussy’s editions and sketches, critical and interpretative approaches, textual and cultural-historical analysis, and his legacy in performance, recording, composition and arrangement.