Major Threats to Endangered Orchids of Victoria, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Central Native Vegetation Plan

© North Central Catchment Management Authority 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the North Central Catchment Management Authority. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Community Engagement, North Central Catchment Management Authority, PO Box 18, Huntly Vic 3551. Telephone: 03 5448 7124 ISBN 0 9578204 0 2 Front cover images: David Kleinert, North Central Catchment Management Authority Back cover images: Adrian Martins, Paul Haw, David Kleinert All other images: North Central Catchment Management Authority North Central Catchment Management Authority PO Box 18 Huntly Vic 3551 Telephone: 03 5448 7124 Facsimile: 03 5448 7148 www.nccma.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the North Central Catchment Management Authority (CMA) and its employees do not guarantee that the information contained in this publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. The North Central Catchment Management Authority therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on the contents of this publication. The North Central CMA Native Vegetation Plan is Ministerially endorsed. The plan outlines the framework for native vegetation management in the North Central region, describes the strategic direction for native vegetation and includes the regional approach to Net Gain. ii Acknowledgements The completion of the North Central Native Vegetation Plan has been assisted by funding from the Catchment and Water Division of DSE (formerly NRE) and Environment Australia through the Natural Heritage Trust (Bushcare). -

Intro Outline

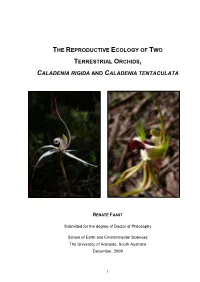

THE REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF TWO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS, CALADENIA RIGIDA AND CALADENIA TENTACULATA RENATE FAAST Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide, South Australia December, 2009 i . DEcLARATION This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution to Renate Faast and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis (as listed below) resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University's digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australasian Digital Theses Program (ADTP) and also through web search engines. Published works contained within this thesis: Faast R, Farrington L, Facelli JM, Austin AD (2009) Bees and white spiders: unravelling the pollination' syndrome of C aladenia ri gída (Orchidaceae). Australian Joumal of Botany 57:315-325. Faast R, Facelli JM (2009) Grazrngorchids: impact of florivory on two species of Calademz (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 57:361-372. Farrington L, Macgillivray P, Faast R, Austin AD (2009) Evaluating molecular tools for Calad,enia (Orchidaceae) species identification. -

Conservation Advice Pterostylis Despectans Lowly Greenhood

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister’s delegate approved this Conservation Advice on 16/12/2016 . Conservation Advice Pterostylis despectans lowly greenhood Conservation Status Pterostylis despectans (lowly greenhood) is listed as Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act). The species is eligible for listing as prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as Endangered under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). Species can also be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl The main factors that are the cause of the species being eligible for listing in the Endangered category are its restricted and fragmented distribution; and its declining population due to continuing threats. Description The lowly greenhood (Orchidaceae) is a herbaceous perennial geophyte that remains dormant underground as a tuber from late summer into early winter. In late winter (May to June) it develops a rosette of six to ten basal leaves and three or four stem-sheathing bract-like leaves above (DSE 2014; OEH 2014; Quarmby 2010). The rosette leaves are 10 - 20 mm long and 6 - 9 mm wide. The flower stem is produced between late October and December and the leaves shrivel up by the time the flowers mature. The flower stem is up to 80 mm tall, though often only reaching 20 - 30mm, with scaly bracts. -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard No. 10, 2003 MONDAY, 8 SEPTEMBER 2003 FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SIXTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2003 Month Date February 4, 5, 6 March 3, 4, 5, 6, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27 May 13, 14, 15 June 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26 August 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 September 8, 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 October 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 27, 28, 29, 30 November 3, 4, 24, 25, 26, 27 December 1, 2, 3, 4 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SIXTH PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators Hon. Nick Bolkus, George Henry Brandis, Hedley Grant Pearson Chapman, John Clifford Cherry, Hon. -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia. -

Draft Survey Guidelines for Australia's Threatened Orchids

SURVEY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIA’S THREATENED ORCHIDS GUIDELINES FOR DETECTING ORCHIDS LISTED AS ‘THREATENED’ UNDER THE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ACT 1999 0 Authorship and acknowledgements A number of experts have shared their knowledge and experience for the purpose of preparing these guidelines, including Allanna Chant (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Allison Woolley (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment), Andrew Brown (Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation), Annabel Wheeler (Australian Biological Resources Study, Australian Department of the Environment), Anne Harris (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), David T. Liddle (Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, and Top End Native Plant Society), Doug Bickerton (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), John Briggs (New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage), Luke Johnston (Australian Capital Territory Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate), Sophie Petit (School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia), Melanie Smith (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Oisín Sweeney (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), Richard Schahinger (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment). Disclaimer The views and opinions contained in this document are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and while reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. -

Biodiversity Summary: Port Phillip and Westernport, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Native Orchid Society South Australia

Journal of the Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc PRINT POST APPROVED VOLUME 25 NO. 8 PP 54366200018 SEPTEMBER 2001 NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA POST OFFICE BOX 565 UNLEY SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5061 The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of orchids through the preservation of natural habitat and through cultivation. Except with the documented official representation from the Management Committee no person is authorised to represent the society on any matter. All native orchids are protected plants in the wild. Their collection without written Government permit is illegal. PRESIDENT: SECRETARY: Bill Dear Cathy Houston Telephone: 82962111 Telephone: 8356 7356 VICE-PRESIDENT David Pettifor Tel. 014095457 COMMITTEE David Hirst Thelma Bridle Bob Bates Malcolm Guy EDITOR: TREASURER Gerry Carne Iris Freeman 118 Hewitt Avenue Toorak Gardens SA 5061 Telephone/Fax 8332 7730 E-mail [email protected] LIFE MEMBERS Mr R. Hargreaves Mr G. Carne Mr L. Nesbitt Mr R. Bates Mr R. Robjohns Mr R Shooter Mr D. Wells Registrar of Judges: Reg Shooter Trading Table: Judy Penney Field Trips & Conservation: Thelma Bridle Tel. 83844174 Tuber Bank Coordinator: Malcolm Guy Tel. 82767350 New Members Coordinator David Pettifor Tel. 0416 095 095 PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian The Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc. while taking all due care, take no responsibility for the loss, destruction or damage to any plants whether at shows, meetings or exhibits. Views or opinions expressed by authors of articles within this Journal do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Management. We condones the reprint of any articles if acknowledgement is given. -

National Recovery Plan for Twenty-One Threatened Orchids in South-Eastern Australia

DRAFT for public comment National Recovery Plan for Twenty-one Threatened Orchids in South-eastern Australia Mike Duncan and Fiona Coates Prepared by Mike Duncan and Fiona Coates, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg, Victoria Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, March 2010. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74242-224-4 (online) This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Duncan, M. -

Biodiversity Summary: Wimmera, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Lowly Greenhood Pterostylis Despectans

Action Statement Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 No. 123 Lowly Greenhood Pterostylis despectans Description and distribution The Lowly Greenhood Pterostylis despectans (Nicholls) M.A. Clem. et D.L. Jones, is a small, inconspicuous, deciduous, terrestrial orchid. After an autumn dormancy survived by the root tuber, a rosette of five to ten leaves 1-1.8cm long and 6-9mm wide, appears in June (Backhouse and Jeanes 1995, Bishop 1996, Walsh and Entwisle 1994). The three or four stem-leaves are reduced to sheathing bracts. The rosette withers before flowering time. The flowering stem reaches 5-8cm tall (Walsh and Entwisle 1994), though it is often only 2- 3cm (Jones 1988). During the two to three month flowering period (December to January), it produces up to six short, stout flowers which are translucent grey-green to brown, very similar Lowly Greenhood Pterostylis despectans to the colour of the leaf litter in which it grows. These flowers are on slender stalks 1-3cm long, and open one at a time, facing downwards, often touching the soil, with their long sepals. The dark brown labellum, a specialised petal, springs closed when an insect or small object touches it, and has 6-18 pairs of marginal hairs (Walsh and Entwisle 1994, Jones 1988) as well as a pair of prominent, erect hairs at its base, which is constricted. The Lowly Greenhood was originally described as Pterostylis rufa R. Br. var. despectans by Nicholls. It has also been informally referred to as Pterostylis R. Br. var. despectans (Blackmore et Clemesha). In 1989 it was classified as a separate species Pterostylis despectans by Distribution in Victoria Clements and Jones (M.A. -

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (27/4/2006) by Mark A. Clements

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (27/4/2006) by Mark A. Clements and David L. Jones Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P-H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name.