Old Problems.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford AHSN Year 5 Q1 Report

Oxford AHSN Year 5 Q1 Report For the quarter ending 30 June 2017 Professor Gary A Ford CBE FMedSci ‘From Assurance to Inquiry’ – The Oxford AHSN Patient Safety Collaborative Annual Conference welcomed over 90 delegates to our third annual conference held on 25 May 2017. Read a full report here Delegate comments about the conference: ‘Assurance is never enough, every incident has lessons to be heard and protecting our customers - brilliant’. ‘I feel more empowered to include patients in my safety work’. ‘interesting variety of speakers’ Contents Chief Executive’s Review 2 Case Studies 3 Operational Overview 14 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) 18 Programmes and Themes Best Care 21 Clinical Innovation Adoption 24 Research and Development 39 Strategic and Industry Partnerships 40 Informatics 44 Patient and Public Involvement, Engagement and Experience 47 Patient Safety 49 Stakeholder Engagement and Communications 62 Finance 67 Appendix A - Review against the Business Plan milestones 68 Appendix B – Matrix of Metrics 76 Appendix C– Risk Register and Issues Log 82 Appendix D- Oxford AHSN case studies published in quarterly reports 2013-2017 87 1 Chief Executive’s Review This quarter has been very productive across all our programmes. The Strategic and Industry Partnerships team has been very active in supporting major grant applications for our partners and running and supporting several key events in the region. Clinical Innovation Adoption has initiated 11 new projects in the quarter including important medical devices to improve patient safety. Best Care has completed its restructuring and has secured £500k of new funding to sustain 5 clinical networks. With support from industry, a new Inflammatory Bowel Disease clinical network is being formed, led by Professor Simon Travis. -

Your Hospitals the Same Hospital? Where Can I Get the Information I Need in Most Cases You Will

hospital Reading Primary Care Trust your Choosing PHOTOGRAPHY COPYRIGHT: ALAMY, GETTY, JOHN BIRDSALL, NHS LIBRARY, REX, SPL, ZEFA/CORBIS copy of this booklet is also Crown copyright 2005. available on: www.nhs.uk A www.berkshire.nhs.uk/reading Tel: 0118 982 2829 Berkshire RG30 2BA Reading 57-59 Bath Road Reading Primary Care Trust Patient Advice and Liaison Service For more help with choosing your hospital, contact: © 270744/167 What is patient choice? Things to think about If you and your GP decide that you need to see a specialist Where can I go for treatment? for further treatment, you can now choose where to have You might already have experience of a particular hospital or know someone who has. Now you can choose – where would you like to go? Or, if you like, your treatment from a list of hospitals or clinics. From April, your GP can recommend a hospital where you can be treated. you may have an even bigger choice – full details will be How do I find out more information on the NHS website (www.nhs.uk). about my condition? Your GP should be able to give you the answers to some of the questions This guide explains more about how the process works. you have. Or contact NHS Direct: visit www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk or call It also gives you answers to some questions you may have. 0845 4647 and ask to speak to a health information advisor. Plus, there are details of the hospitals you can choose and How long will it take? some information to help you choose the one that will be How quickly do you want to be treated? Would you be willing to travel best for you. -

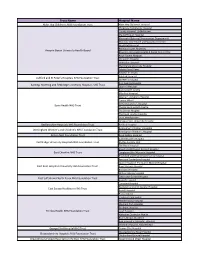

Trust Name Hospital Name

Trust Name Hospital Name Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust Alder Hey Children's Hospital Chepstow Community Hospital County Hospital, Griffithstown Maindiff Court Hospital Mamhalid (External Procurement Department) Monnow Vale Health and Social Care Centre Nevill Hall Hospital Redwood Suite, Rhymney Aneurin Bevan University Health Board Rhymney Integrated Health & Social Care Centre Royal Gwent Hospital St Cadoc's Hospital St Woolos Hospital The Grange University Hospital Ysbyty Ystrad Fawr Ysbyty'r tri Chwm Ashford Hospital Ashford and St Peter's Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust St Peter's Hospital King George Hospital Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust Queen's Hospital Barking Birth Centre Mile End Hospital Newham University Hospital Canary Wharf St Bartholomew's Hospital Barts Health NHS Trust The Barkantine Birth Centre The Dental Hospital The Royal London Hospital Trust Headquarters Whipps Cross University Hospital Bedfordshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Bedford Hospital Birmingham Children's Hospital Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust Birmingham Women's Hospital Bolton NHS Foundation Trust Royal Bolton Hospital Addenbrooke's Hospital Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Ely Day Surgery Unit The Rosie Hospital Macclesfield District General Hospital East Cheshire NHS Trust Congleton War Memorial Hospital Knutsford and District Community Hospital Kent and Canterbury Hospital Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation -

Chief Registrar Recruitment 2020/21 Recruiting NHS Organisations And

Chief Registrar recruitment 2020/21 Recruiting NHS organisations and contact details (updated 02.04.2020) Please contact the recruitment lead if you are interested in one of these chief registrars’ posts Trust/Health Board Hospital Specialty Number of Lead contact(s) for Lead contact(s) email address chief recruitment registrar posts available Barts Health NHS Trust Royal London Hospital Surgery 1 Christopher Kennedy [email protected] Barts Health NHS Trust Whipps Cross Hospital Medicine 1 Dhrupsha Kara [email protected] Barts Health NHS Trust Newham University Emergency Medicine x1 2 Dr Emma Young [email protected] Hospital another specialty x1 Barts Health NHS Trust St Bartholomew’s No preference on speciality- 2 Dr Mark Westwood [email protected] Hospital dependent on applicants Buckinghamshire Stoke Mandeville Acute and GIM 1 Dr Tina O’Hara [email protected] Healthcare NHS Trust Hospital Croydon Health Care NHS Croydon University Anaesthetics and Paediatrics 2 Dr Gita Menon [email protected] Trust Hospital Croydon Health Care NHS Croydon University Not stated 1 Sally Lewis [email protected] Trust Hospital Dartford and Gravesham Darent Valley Hospital General medicine 1 Steve Fenlon [email protected] NHS Trust Dudley Group NHS Russells Hall Hospital Not stated 1 Rebecca Edwards [email protected] Foundation Trust Trust/Health Board Hospital Specialty Number of Lead contact(s) for Lead contact(s) email address chief recruitment registrar posts available East and North Lister Hospital, Stevenage Medicine -

NICE-FIT-Newsletter-May-2018.Pdf

OVERALL STUDY RECRUITMENT UPDATE - APRIL 2018 (as of 29/04/2018) Screening lists sent Total Status Screened Recruited (previous to date month) Croydon Health Services NHS Trust Recruiting 18 (16) 125 87 (60%) 301 Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust - West Middlesex University Hospital Recruiting 19 (13) 102 48 (47%) 153 Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust - Chelsea and Westminster Hospital Recruiting 2 (5) 8 3 (38%) 89 Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 16 (14) 105 59 (56%) 250 Epsom & St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust Recruiting 28 (36) 152 122 (80%) 529 St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 5 (8) 17 8 (47%) 63 The Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 13 (11) 67 25 (37%) 51 London North West Healthcare NHS Trust - St Mark's Hospital Recruiting 1 (7) 16 7 (44%) 63 London North West Healthcare NHS Trust - Ealing Hospital Recruiting 8 (12) 37 19 (51%) 107 Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Recruiting 7 (0) 80 49 (61%) 83 Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust Recruiting 11 (17) 103 60 (58%) 102 Guys' and St Thomas' Hospital NHS Foundation Trust In Set Up King's College Hospital - Princess Royal Hospital In Set Up King's College Hospital - Denmark Hill In Set Up 517 London Total 865 (60%) 1847 Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 61 202 Dorset County Hospital Recruiting 16 58 Surrey & Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust Recruiting 56 86 University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 42 58 Wrightington, Wigan -

Isils for Organizations in the UK and Its Dependencies

ISILs for organizations in the UK and its dependencies Last updated: 02 September 2019 Current ISILs This table lists current ISILs for organizations in the UK and its dependencies. It is arranged in alphabetical order by organization name. Active ISILs ISIL Name Variant or previous Address Town/City Postcode name(s) GB-UK-AbCCL Aberdeen City Council Library Aberdeen City Libraries; Central Library, Rosemount Aberdeen AB25 1GW and Information Service Aberdeen Library & Viaduct Information Services GB-StOlALI Aberdeenshire Libraries Aberdeenshire Library Meldrum Meg Way Oldmeldrum AB51 0GN and Information Service; ALIS GB-WlAbUW Aberystwyth University Prifysgol Aberystwyth, Hugh Owen Library, Penglais Aberystwyth SY23 3DZ AU; University of Campus Wales, Aberystwyth; Prifysgol Cymru, Aberystwyth GB-UkLoJL Aga Khan Library IIS-ISMC Joint Library; 10 Handyside Street London N1C 4DN Library of the Institute of Ismaili Studies and the Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations (Aga Khan University) GB-UkLiAHC Alder Hey Children’s NHS FT Education Centre, Eaton Road Liverpool L12 2AP GB-UkChARU Anglia Ruskin University University Library, Rivermead Chelmsford CM1 1SQ Campus, Bishops Hall Lane GB-UkBuAEC Anglo-European College of AECC 13-15, Parkwood Road Bournemouth BH5 2DF Chiropractic GB-UkLtASL Angmering School Library Angmering School Library, Littlehampton BN16 4HH The Angmering School, Station Road, Angmering GB-StAnAA ANGUSalive Angus Libraries; Library Support Services, Forfar DD8 1BA ANGUSalive libraries; 50/56, West High Street -

(London), FRCS (Plast) Consultant Plastic Surgeon GMC Number

Mr Richard Henry James Baker MB BChir, MA, MRCS (Edin), MD (Res)(London), FRCS (plast) Consultant Plastic Surgeon GMC number: 4767884 ML Experts Consulting 16 Caudwell Close Coleford Gloucestershire GL16 8EY 0207 118 1134 [email protected] Qualifications European Diploma!In Hand Surgery June 2014 FRCS(Plast) 1 & 2 September 2012 M.D. (Res) (London) September 2008 M.R.C.S. (Edinburgh) May 2004 M.A. (Cambridge)! June 2001 M.B, B.Chir (Cambridge) December 2000 ! Present Appointment Consultant Plastic Surgeon, Wexham Park Hospital Summary I was appointed as Specialty Training Registrar in Plastic Surgery in October 2008 beginning at the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead and rotating to the Royal Free Hospital, London, and finally Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford. I have undertaken courses in microsurgery, hand surgery, burns and trauma as well as the BSSH Instructional Courses. My research into insulin and its anti-scarring properties enabled me to achieve an MD(Res) and I’ve continued my academic activities undertaking audits, giving presentations and writing papers. I have completed Training Interface Group Fellowships in Reconstructive Cosmetic Surgery in Leicester and Hand and Wrist Surgery in Nottingham culminating in the European Diploma of Hand Surgery (2014). I have visited prestigious international units: E’Da Hospital in Taiwan, the Kleinert Institute in Louisville and Santander (Francisco Del Pinal) in Spain. I was appointed locum Consultant Plastic Surgeon at Wexham Park Hospital in August 2015, becoming substantive in July 2017, and specialise in hand & wrist surgery, hypospadias and general plastic surgery. Consultant Plastic Surgeon Wexham Park Hospital, 12.07.2017 – Locum Consultant Plastic Surgeon Wexham Park Hospital, 05.08.2015 – 12.07.2017 Training Interface Group Fellowship in Hand and Wrist Surgery Nottingham University Hospitals, 01.08.2014 – 04.08.2015 Institute for Hand & Wrist and Plastic Surgery Santander, Spain 25.05.14 – 25.07.14. -

National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating Hospitals List England

Updated June 2014 National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating hospitals list The total number of hospitals signed up to participate in NCAA is 177. England Avon, Gloucestershire and Wiltshire NCAA participants Cheltenham General Hospital Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Gloucestershire Royal Hospital Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Royal United Hospital Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust Southmead Hospital, Bristol North Bristol NHS Trust The Great Western Hospital Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust Non-NCAA participants Weston General Hospital Weston Area Health NHS Trust Birmingham and Black Country NCAA participants Alexandra Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Birmingham Heartlands Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust City Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Good Hope Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust Manor Hospital Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust Russells Hall Hospital The Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Trust Sandwell General Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Solihull Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust Worcestershire Royal Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Non-NCAA participants Hereford County Hospital Wye Valley NHS Trust New Cross Hospital The Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Supported by Resuscitation -

Regional Trauma Networks V12

Regional Trauma Networks v12 Network and MTC: Northern: MTC’s: - Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Victoria Infirmary - South Tees Hospitals NHS Trust, James Cook University Hospital South Cumbria and Lancashire: MTC: Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Preston Hospital Yorkshire and Humber Networks: • North Yorkshire and Humberside: MTC: Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Hull Royal Infirmary • West Yorkshire: MTC: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust - Leeds General Infirmary • South Yorkshire: MTC’s: - Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust - Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Greater Manchester: Collaborative MTC’s: - Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust - Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust: o Manchester Royal Infirmary o Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital - University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust Merseyside and Cheshire: Collaborative MTC’s: - Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust - The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust (Neuro) - Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool Midlands Trauma networks: • Birmingham, Black Country, Hereford & Worcester: MTC’s: - Birmingham Children’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust - University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Queen Elizabeth Hospital 1 Regional Trauma Networks – V12 • North West Midlands & North Wales: MTC: University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, Royal Stoke University Hospital • Central England: MTC: University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust East Midlands: MTC: Nottingham University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Queen’s Medical Centre East of England: MTC: Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Addenbrookes North East London and Essex: MTC: Barts Health, Royal London Hospital North West London: MTC: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, St Mary’s Hospital South West London and Surrey: MTC: St. -

Driving Improvement: Case Studies from Eight NHS Trusts

Driving improvement Case studies from eight NHS trusts JUNE 2017 Our purpose The Care Quality Commission is the independent regulator of health and adult social care in England. We make sure that health and social care services provide people with safe, effective, compassionate, high-quality care and we encourage care services to improve. Our role z We register health and adult social care providers. z We monitor and inspect services to see whether they are safe, effective, caring, responsive and well-led, and we publish what we find, including quality ratings. z We use our legal powers to take action where we identify poor care. z We speak independently, publishing regional and national views of the major quality issues in health and social care, and encouraging improvement by highlighting good practice. Our values Excellence – being a high-performing organisation Caring – treating everyone with dignity and respect Integrity – doing the right thing Teamwork – learning from each other to be the best we can b DRIVING IMPROVEMENT – CASE STUDIES FROM EIGHT NHS TRUSTS Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................2 THE TRUSTS THAT WE INTERVIEWED ...............................................4 NHS STAFF SURVEY ...........................................................................6 KEY THEMES .......................................................................................8 UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS OF MORECAMBE BAY NHS FOUNDATION TRUST ...............................................................14 -

Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust

Schedule of Accreditation issued by United Kingdom Accreditation Service 2 Pine Trees, Chertsey Lane, Staines-upon-Thames, TW18 3HR, UK Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust Issue No: 006 Issue date: 05 August 2021 Frimley Health NHS Foundation Contact: Governance / Quality Department Trust Tel: +44 (0) 1276 522194 / 1276 522541 / 1276 522175 Frimley Park Hospital, 8086 E-Mail: [email protected] Frimley Website: www.nhspathology.fph.nhs.uk Accredited to Camberley ISO 15189:2012 GU16 7UJ Testing performed by the Organisation at the locations specified below Locations covered by the organisation and their relevant activities Laboratory locations: Location details Activity Location code Address Local contact Histology RBH Cellular Pathology Department Amanda Babington Immunocytochemistry Tel: +44 (0) 118322 8201 Frozen Section for intraoperative Royal Berkshire Hospital diagnosis. E-Mail: London Road Interpretive microscopy Amanda.babington@Roy Non-Gynae Cytology Reading alberkshire.nhs.uk RG1 5AN Address Local contact Histology WPH Department of Histopathology Stephen Brown Immunocytochemistry Tel: +44 (0) 300 615 Frozen Section for intraoperative Wexham Park Hospital 3458 diagnosis. Slough E-Mail: Interpretive microscopy Non-Gynae Cytology (cell block or clot Berkshire [email protected] processing and staining) SL2 4HL Local contact Address Harvi Atwal OSNA (one-step nucleic acid HH Tel: +44 (0) 118 322 amplification) Heatherwood Hospital 7738 High St Ascot E-Mail: SL5 8AA Harvinder.Atwal@royalbe rkshire.nhs.uk Assessment Manager: -

Name of Hospital/Trust ARK Champion Wexham Park Hospital Veronica Garcia-Arias South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Sath N

Name of Hospital/Trust ARK Champion Wexham Park Hospital Veronica Garcia-Arias South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Sath Nag Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust Mridula Rajwani Southport & Ormskirk Hospitals NHS Trust Katherine Gray Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust Jean Odriscoll Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust Varun Nelatur South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust (NI) Bernie Mccullagh Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust Damien Mack Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust Neil Powell York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Damian Mawer Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Tim Hills Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust Rosie Fok North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust Clare Hamson London North West Healthcare NHS Trust (Northwick Park) Cassandra Watson Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust Robert Porter Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Ruth Mcewen Wye Valley NHS Trust Alison Johnson Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust Bruce Stewart Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust Stuart Bond Northern Health and Social Care Trust (NI) Aaron Nagar Western Health and Social Care Trust, Altnagelvin Area Hospital (NI) Cairine Gormley Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, NHS Lothian Clifford Leen East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Foundation Trust Immo Weichert North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust Rebecca Alexander Southern Health and Social Care Trust Geraldine Conlon Bingham Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust Samantha Dymond The Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust Mandy Slatter Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Gloria Kiapi Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board - Bangor Karen Mottart Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust Ashley Price North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust Mariyam Mirfenderesky Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Liz Sheridan Airedale NHS Foundation Trust Kevin Frost Wirral University Teaching Hospital David Harvey Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Amanda Pegden .