Full Text Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating Hospitals

Updated June 2018 National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating Hospitals The total number of hospitals signed up to participate in NCAA is 197. England Birmingham and Black Country Non-participant New Cross Hospital The Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Participant Alexandra Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Birmingham Heartlands Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust City Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Good Hope Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust Hereford County Hospital Wye Valley NHS Trust Manor Hospital Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust Russells Hall Hospital The Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Trust Sandwell General Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Solihull Hospital Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust Worcestershire Royal Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Central England Participant George Eliot Hospital George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust Glenfield Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Kettering General Hospital Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Leicester General Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Leicester Royal Infirmary University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Northampton General Hospital Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust Hospital of St Cross, Rugby University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust University Hospital Coventry University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust -

ABCD Nationwide Audit of Freestyle Libre (FSL)

ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre (FSL) Dr Harshal Deshmukh MRCP MPH PhD NIHR Clinical Lecturer in Endocrinology and Diabetes Dr Emma Wilmot Dr Chris Walton Dr Bob Ryder Prof Thozhukat Sathyapalan ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre DISCLOSURES Disclosures • EW has received personal fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Dexcom, Diasend, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Aventis • BR has received speaker fees, and/or consultancy fees and/or educational sponsorships from AstraZeneca, BioQuest, GI Dynamics, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis and Takeda • HD TS and CW have no relevant disclosures Funding The ABCD nationwide Freestyle Libre audit is supported by a grant from Abbott UK. The audit was independently initiated and performed by ABCD, and the authors remain independent in the analysis and preparation of this report. ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre • FreeStyle Libre is a flash glucose monitoring system which monitors interstitial glucose levels • Consists of a sensor with a microfilament, worn on the back of the arm and a hand- held reader • When the reader unit is passed over the sensor, it shows the interstitial glucose levels • The sensor lasts for 14 days, then needs to be replaced ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre ABCD FSL Audit Main Objectives The ABCD FSL Audit aims to explore the impact of the FSL on the following: . HbA1c . Hypoglycaemia awareness . Resource utilisation: hospital admissions . User satisfaction . Diabetes related distress . Discontinuation rate and causes ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre Methods ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre • Audit conducted in 114 centres in the UK • A secure IT tool was developed on the NHS computer network, N3, to make this process as easy and user friendly as possible ABCD nationwide audit of FreeStyle Libre . -

List 2018 a 18/0347 8 Abelia Close, West End, Woking, Surrey, GU24 9PG 18/0115 24 Academy Close, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4BU

List 2018 A 18/0347 8 Abelia Close, West End, Woking, Surrey, GU24 9PG 18/0115 24 Academy Close, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4BU 18/0491 Units 1-5 Admiralty Way, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 3DT 18/0694 Unit 7, Phase 4 Albany Park, Camberley, Surrey, GU16 7PL 18/0806 16 Albert Road, Bagshot, Surrey, GU19 5QJ 18/0630 1 Alexandra Avenue, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 3BG 18/1015 Sandhurst Chalet, Alfriston Road, Deepcut, Camberley, Surrey, GU16 6QS 18/0521 The Surgery, 39 All Saints Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU18 5SQ 18/0383 22 Alpha Road, Chobham, Woking, Surrey, GU24 8NF 18/0860 5 Alphington Avenue, Frimley, CAMBERLEY, GU16 8LA 18/0024 31 Alphington Avenue, Frimley, Camberley, Surrey, GU16 8LL 18/0063 45 Alphington Avenue, Frimley, Camberley, Surrey, GU16 8LL 18/0717 8 Amber Hill, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 1EB 18/0673 27 Ambleside Close, Mytchett, Camberley, Surrey, GU16 6DG 18/0394 1 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, Gu18 5TA 18/0844 25 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, GU18 5TA 18/0199 27 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU16 6DG 18/0392 32A Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU16 5TA 18/0657 32A Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU16 5TA 18/0271 87 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU18 5UH 18/0699 137 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, GU18 5UL 18/0345 142 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU18 5UN 18/0037 153 Ambleside Road, Lightwater, Surrey, GU18 5UN 18/0577 11 Anderson Place, Bagshot, Surrey, GU19 5LX 18/0060 6 Ardrossan Avenue, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 1DD 18/0830 15 Arthur Close, Bagshot, GU19 5QT 18/0889 16 Arundel Road, Camberley, GU15 1DL -

UK Clinical Teaching Fellows Forum 2019

UK Clinical Teaching Fellows Forum 2019 In partnership with The Academy of Medical Educators Saturday 8 June 2019 Postgraduate Education Centre, Frimley Park Hospital, Surrey IMPROVING CARE THROUGH TEACHING EXCELLENCE Academy of Medical Educators, Neuadd Meirionnydd, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4YS Email: [email protected] Telephone: 02920 687206 Charity no: 1128988 Company no: 5965178 www.medicaleducators.org Programme Time Speaker Session Venue 9.15 - 9.45 Registration and coffee (Entrance hall) 9.45 – 10.00 Dr James Fisher & Introduction Lecture Dr Lewis Hendon-John Theatre Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust 10.00– 10.15 Neil Dardis Welcome Talk - Engaging the board Lecture Theatre Chief Executive, Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust 10.15 - 10.35 Professor Jacky Hayden The Current State of Medical Education Lecture Theatre President Academy of Medical Educators 10.35 - 11.05 Short Presentations (plenary) Lecture Theatre The Great Escape: Exploring the impact of escape rooms in medical education Webster R, Durkan N, Leylabi R, Smethurst K, Royal Victoria Infirmary Implementing wilderness medicine training for undergraduate medical education: a success story Schulz J, Warrington J, Maguire C, Georgi T, Hearn R, King’s College London Immersive Confusional Experience of Delirium (ICED): The use of an interactive, web-based game to teach undergraduates about delirium Webb L, van't Hoff C, Jacobs C, Finnegan D, Ipe A, Jones K, Great Western Hospital 11.05 – 11.15 Rapid Poster Summary Session (plenary) 11.15 – 11.45 Coffee and biscuits, -

HSMR June09 Choices

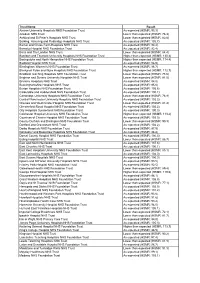

Trust Name Result Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 93.3) Airedale NHS Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 76.3) Ashford and St Peter's Hospitals NHS Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 82.8) Barking, Havering and Redbridge Hospitals NHS Trust As expected (HSMR: 105.7) Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS Trust As expected (HSMR: 94.4) Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 92.4) Barts and The London NHS Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 84.4) Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Higher than expected (HSMR: 130.4) Basingstoke and North Hampshire NHS Foundation Trust Higher than expected (HSMR: 114.4) Bedford Hospital NHS Trust As expected (HSMR: 96.9) Birmingham Women's NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 96.7) Blackpool Fylde and Wyre Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Higher than expected (HSMR: 112.7) Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 78.6) Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 81.5) Bromley Hospitals NHS Trust As expected (HSMR: 94.0) Buckinghamshire Hospitals NHS Trust As expected (HSMR: 95.6) Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 105.6) Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 100.1) Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: 78.9) Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust As expected (HSMR: 102.2) Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Lower than expected (HSMR: -

Suspected Cancer Fast Track Referral

Suspected Cancer Frimley Health Fast Track Referral NHS Foundation Trust IMPORTANT information about your appointment Your doctor/dentist has requested you are Hospital addresses seen by a specialist or have a test within the next two weeks. You will be seen at one of the following hospitals: You may be offered the opportunity to book an Frimley Park Sites: appointment before you leave the surgery, or will be offered an appointment by telephone Frimley Park Hospital at the earliest opportunity. Portsmouth Road, Surrey, GU16 7UJ It is important you make yourself available Aldershot Centre for Health and attend this appointment. Hospital Hill, Aldershot, Hampshire GU11 1AY Should I be worried? Fleet Community Hospital The need for an early appointment does not mean Church Road, Fleet, Hampshire, GU51 4LZ you have cancer, however your doctor/dentist would like you to be seen by a specialist as soon as Farnham Hospital possible. Hale Road, Farnham, Surrey, GU9 9QL What is a Suspected Cancer The Bracknell Clinic Fast Track referral? Eastern Gate, Brants Bridge, Bracknell, Berkshire This referral is to ensure anyone with symptoms/ RG12 9BG initial test results that may be suspicious of cancer will be seen by a specialist or have a specialist test Heatherwood and Wexham Sites: within two weeks. Wexham Park Hospital, The aim is to exclude cancer or provide diagnosis, Wexham Street, Slough, SL2 4HL intervention and treatment, if required, at the earliest opportunity. Heatherwood Hospital, London Road, Ascot, SL5 8AA What happens now? King Edward VII Hospital, St Leonards Road, Windsor, SL4 3DP • You will be helped to book an appointment before you leave the surgery or you may receive St Mark’s Hospital, an appointment by telephone, please accept a St Mark’s Road, Maidenhead, SL6 6DU telephone call from an unknown number. -

Oxford AHSN Year 5 Q1 Report

Oxford AHSN Year 5 Q1 Report For the quarter ending 30 June 2017 Professor Gary A Ford CBE FMedSci ‘From Assurance to Inquiry’ – The Oxford AHSN Patient Safety Collaborative Annual Conference welcomed over 90 delegates to our third annual conference held on 25 May 2017. Read a full report here Delegate comments about the conference: ‘Assurance is never enough, every incident has lessons to be heard and protecting our customers - brilliant’. ‘I feel more empowered to include patients in my safety work’. ‘interesting variety of speakers’ Contents Chief Executive’s Review 2 Case Studies 3 Operational Overview 14 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) 18 Programmes and Themes Best Care 21 Clinical Innovation Adoption 24 Research and Development 39 Strategic and Industry Partnerships 40 Informatics 44 Patient and Public Involvement, Engagement and Experience 47 Patient Safety 49 Stakeholder Engagement and Communications 62 Finance 67 Appendix A - Review against the Business Plan milestones 68 Appendix B – Matrix of Metrics 76 Appendix C– Risk Register and Issues Log 82 Appendix D- Oxford AHSN case studies published in quarterly reports 2013-2017 87 1 Chief Executive’s Review This quarter has been very productive across all our programmes. The Strategic and Industry Partnerships team has been very active in supporting major grant applications for our partners and running and supporting several key events in the region. Clinical Innovation Adoption has initiated 11 new projects in the quarter including important medical devices to improve patient safety. Best Care has completed its restructuring and has secured £500k of new funding to sustain 5 clinical networks. With support from industry, a new Inflammatory Bowel Disease clinical network is being formed, led by Professor Simon Travis. -

Your Hospitals the Same Hospital? Where Can I Get the Information I Need in Most Cases You Will

hospital Reading Primary Care Trust your Choosing PHOTOGRAPHY COPYRIGHT: ALAMY, GETTY, JOHN BIRDSALL, NHS LIBRARY, REX, SPL, ZEFA/CORBIS copy of this booklet is also Crown copyright 2005. available on: www.nhs.uk A www.berkshire.nhs.uk/reading Tel: 0118 982 2829 Berkshire RG30 2BA Reading 57-59 Bath Road Reading Primary Care Trust Patient Advice and Liaison Service For more help with choosing your hospital, contact: © 270744/167 What is patient choice? Things to think about If you and your GP decide that you need to see a specialist Where can I go for treatment? for further treatment, you can now choose where to have You might already have experience of a particular hospital or know someone who has. Now you can choose – where would you like to go? Or, if you like, your treatment from a list of hospitals or clinics. From April, your GP can recommend a hospital where you can be treated. you may have an even bigger choice – full details will be How do I find out more information on the NHS website (www.nhs.uk). about my condition? Your GP should be able to give you the answers to some of the questions This guide explains more about how the process works. you have. Or contact NHS Direct: visit www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk or call It also gives you answers to some questions you may have. 0845 4647 and ask to speak to a health information advisor. Plus, there are details of the hospitals you can choose and How long will it take? some information to help you choose the one that will be How quickly do you want to be treated? Would you be willing to travel best for you. -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Hospital List for Gold Option

GEN3461_97000805.qxp:GEN3461_97000805 13/7/12 16:13 Page 1 The Royal Bank of Scotland Hospital List for Gold Option England Cheshire Bedfordshire Cheadle BMI The Alexandra Hospital Chester Nuffield Health Grosvenor Hospital Bedford Bedford Hospital (Chester) Biddenham BMI The Manor Hospital Crewe BMI The South Cheshire Private Luton Luton & Dunstable Hospital - Cobham Hospital Clinic Macclesfield Spire Regency Hospital Berkshire Warrington Spire Cheshire Hospital Reading Berkshire Independent Hospital Cleveland Spire Dunedin Hospital Norton Nuffield Health Tees Hospital Slough Spire Thames Valley Hospital Wexham Park Hospital Cornwall - Paragon Suite Truro Duchy Hospital Windsor BMI The Princess Margaret Hospital Cumbria Bristol Carlisle Caldew Hospital Bristol Spire Bristol Hospital Whitehaven West Cumberland Hospital Eye Hospital - Cumbrian Clinic General Hospital Nuffield Health Bristol Hospital Derbyshire Royal Hospital for Sick Children Derby Nuffield Health Derby Hospital Royal Infirmary Devon Buckinghamshire Barnstaple North Devon District Hospital Aylesbury Stoke Mandeville Hospital - Roborough Suite Great Missenden BMI The Chiltern Hospital Exeter Nuffield Health Exeter Hospital High Wycombe BMI The Shelburne Hospital Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital Plymouth Derriford Hospital - The Meavy Clinic Milton Keynes BMI The Saxon Clinic Nuffield Health Plymouth Hospital Cambridgeshire Torquay Mount Stuart Hospital Cambridge Addenbrookes Hospital Spire Cambridge Lea Hospital Dorset Nuffield Health Cambridge Hospital Bournemouth Nuffield Health Bournemouth -

Trust Name Hospital Name

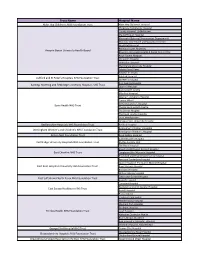

Trust Name Hospital Name Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust Alder Hey Children's Hospital Chepstow Community Hospital County Hospital, Griffithstown Maindiff Court Hospital Mamhalid (External Procurement Department) Monnow Vale Health and Social Care Centre Nevill Hall Hospital Redwood Suite, Rhymney Aneurin Bevan University Health Board Rhymney Integrated Health & Social Care Centre Royal Gwent Hospital St Cadoc's Hospital St Woolos Hospital The Grange University Hospital Ysbyty Ystrad Fawr Ysbyty'r tri Chwm Ashford Hospital Ashford and St Peter's Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust St Peter's Hospital King George Hospital Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust Queen's Hospital Barking Birth Centre Mile End Hospital Newham University Hospital Canary Wharf St Bartholomew's Hospital Barts Health NHS Trust The Barkantine Birth Centre The Dental Hospital The Royal London Hospital Trust Headquarters Whipps Cross University Hospital Bedfordshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Bedford Hospital Birmingham Children's Hospital Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust Birmingham Women's Hospital Bolton NHS Foundation Trust Royal Bolton Hospital Addenbrooke's Hospital Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Ely Day Surgery Unit The Rosie Hospital Macclesfield District General Hospital East Cheshire NHS Trust Congleton War Memorial Hospital Knutsford and District Community Hospital Kent and Canterbury Hospital Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation -

Chief Registrar Recruitment 2020/21 Recruiting NHS Organisations And

Chief Registrar recruitment 2020/21 Recruiting NHS organisations and contact details (updated 02.04.2020) Please contact the recruitment lead if you are interested in one of these chief registrars’ posts Trust/Health Board Hospital Specialty Number of Lead contact(s) for Lead contact(s) email address chief recruitment registrar posts available Barts Health NHS Trust Royal London Hospital Surgery 1 Christopher Kennedy [email protected] Barts Health NHS Trust Whipps Cross Hospital Medicine 1 Dhrupsha Kara [email protected] Barts Health NHS Trust Newham University Emergency Medicine x1 2 Dr Emma Young [email protected] Hospital another specialty x1 Barts Health NHS Trust St Bartholomew’s No preference on speciality- 2 Dr Mark Westwood [email protected] Hospital dependent on applicants Buckinghamshire Stoke Mandeville Acute and GIM 1 Dr Tina O’Hara [email protected] Healthcare NHS Trust Hospital Croydon Health Care NHS Croydon University Anaesthetics and Paediatrics 2 Dr Gita Menon [email protected] Trust Hospital Croydon Health Care NHS Croydon University Not stated 1 Sally Lewis [email protected] Trust Hospital Dartford and Gravesham Darent Valley Hospital General medicine 1 Steve Fenlon [email protected] NHS Trust Dudley Group NHS Russells Hall Hospital Not stated 1 Rebecca Edwards [email protected] Foundation Trust Trust/Health Board Hospital Specialty Number of Lead contact(s) for Lead contact(s) email address chief recruitment registrar posts available East and North Lister Hospital, Stevenage Medicine -

NICE-FIT-Newsletter-May-2018.Pdf

OVERALL STUDY RECRUITMENT UPDATE - APRIL 2018 (as of 29/04/2018) Screening lists sent Total Status Screened Recruited (previous to date month) Croydon Health Services NHS Trust Recruiting 18 (16) 125 87 (60%) 301 Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust - West Middlesex University Hospital Recruiting 19 (13) 102 48 (47%) 153 Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust - Chelsea and Westminster Hospital Recruiting 2 (5) 8 3 (38%) 89 Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 16 (14) 105 59 (56%) 250 Epsom & St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust Recruiting 28 (36) 152 122 (80%) 529 St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 5 (8) 17 8 (47%) 63 The Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 13 (11) 67 25 (37%) 51 London North West Healthcare NHS Trust - St Mark's Hospital Recruiting 1 (7) 16 7 (44%) 63 London North West Healthcare NHS Trust - Ealing Hospital Recruiting 8 (12) 37 19 (51%) 107 Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Recruiting 7 (0) 80 49 (61%) 83 Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust Recruiting 11 (17) 103 60 (58%) 102 Guys' and St Thomas' Hospital NHS Foundation Trust In Set Up King's College Hospital - Princess Royal Hospital In Set Up King's College Hospital - Denmark Hill In Set Up 517 London Total 865 (60%) 1847 Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 61 202 Dorset County Hospital Recruiting 16 58 Surrey & Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust Recruiting 56 86 University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust Recruiting 42 58 Wrightington, Wigan