Notes and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish Narrative Literature with Particular Reference to Tales Belonging to the Ulster Cycle

The role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish narrative literature with particular reference to tales belonging to the Ulster Cycle. Mary Leenane, B.A. 2 Volumes Vol. 1 Ph.D. Degree NUI Maynooth School of Celtic Studies Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy Head of School: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Supervisor: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn June 2014 Table of Contents Volume 1 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I: General Introduction…………………………………………………2 I.1. Ulster Cycle material………………………………………………………...…2 I.2. Modern scholarship…………………………………………………………...11 I.3. Methodologies………………………………………………………………...14 I.4. International heroic biography………………………………………………..17 Chapter II: Sources……………………………………………………………...23 II.1. Category A: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a significant role…………...23 II.2. Category B: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a more limited role………...41 II.3. Category C: Texts in which Cú Chulainn makes a very minor appearance or where reference is made to him…………………………………………………...45 II.4. Category D: The tales in which Cú Chulainn does not feature………………50 Chapter III: Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography…………………………………53 III.1. Cú Chulainn’s conception and birth………………………………………...54 III.1.1. De Vries’ schema………………...……………………………………………………54 III.1.2. Relevant research to date…………………………………………………………...…55 III.1.3. Discussion and analysis…………………………………………………………...…..58 III.2. Cú Chulainn’s youth………………………………………………………...68 III.2.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………68 III.2.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………69 III.2.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..78 III.3. Cú Chulainn’s wins a maiden……………………………………………….90 III.3.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………90 III.3.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………91 III.3.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..95 III.3.4 Further comment……………………………………………………………………...108 III.4. -

The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes

ffVJU*S )UjfáZt ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV KUNO MEYER, Ph.D. THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO. LTD. LONDON: WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 (Reprinted 1937) cJ&íc+u. Ity* rs** "** ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV. KUNO MEYER THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO., Ltd, LONDON : WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 °* s^ B ^N Made and Printed by the Replika Process in Great Britain by PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES &f CO. LTD. 1 2 Bedford Square, London, W.C. i and at Bradford CONTENTS PAGE Peeface, ....... v-vii I. The Death of Conchobar, 2 II. The Death of Lóegaire Búadach . 22 III. The Death of Celtchar mac Uthechaib, 24 IV. The Death of Fergus mac Róich, . 32 V. The Death of Cet mac Magach, 36 Notes, ........ 48 Index Nominum, . ... 46 Index Locorum, . 47 Glossary, ....... 48 PREFACE It is a remarkable accident that, except in one instance, so very- few copies of the death-tales of the chief warriors attached to King Conchobar's court at Emain Macha should have come down to us. Indeed, if it were not for one comparatively late manu- script now preserved outside Ireland, in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh, we should have to rely for our knowledge of most of these stories almost entirely on Keating's History of Ireland. Under these circumstances it has seemed to me that I could hardly render a better service to Irish studies than to preserve these stories, by transcribing and publishing them, from the accidents and the natural decay to which they are exposed as long as they exist in a single manuscript copy only. -

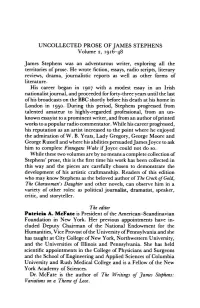

UNCOLLECTED PROSE of JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48

UNCOLLECTED PROSE OF JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48 James Stephens was an adventurous writer, exploring all the territories of prose. He wrote fiction, essays, radio scripts, literary reviews, drama, journalistic reports as well as other forms of literature. His career began in 1907 with a modest essay in an Irish nationalist journal, and proceeded for forty-three years until the last of his broadcasts on the BBC shortly before his death at his home in London in 1950. During this period, Stephens progressed from talented amateur to highly-regarded professional, from an un known essayist to a prominent writer, and from an author of printed works to a popular radio commentator. While his career progi-essed, his reputation as an artist increased to the point where he enjoyed the admiration ofW. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Moore and George Russell and where his abilities persuaded James Joyce to ask him to complete Finnegans Wake if Joyce could not do so. While these two volumes are by no means a complete collection of Stephens' prose, this is the first time his work has been collected in this way and the pieces are carefully chosen to demonstrate the development of his artistic craftmanship. Readers of this edition who may know Stephens as the beloved author of The Crock oJGold, The Charwoman's Daughter and other novels, can observe him in a variety of other roles: as political journalist, dramatist, speaker, critic, and storyteller. The editor Patricia A. McFate is President of the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York. Her previous appointments have in cluded Deputy Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vice Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and she has taught at City College of New York, Northwestern University, and the Universities of Illinois and Pennsylvania. -

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn: the Irish Review, 1911-14

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn The Irish Review 1911-1914 By Ed Mulhall The July 1913 edition of The Irish Review , a monthly magazine of Irish Literature, Art and Science, leads off with an article " Ireland, Germany and the Next War" written under the pseudonym " Shan Van Vocht ". The article is a response to a major piece written by Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes books and a noted writer on international issues, in the Fortnightly Review of February 1903 called "Great Britain and the Next War". Shan Van Vocht takes issue with a central conclusion of Doyle's piece that Ireland's interests are one with Great Britain if Germany were to be victorious in any conflict. Doyle writes: "I would venture to say one word here to my Irish fellow- countrymen of all political persuasions. If they imagine that they can stand politically or economically while Britain falls, they are woefully mistaken. The British Fleet is their one shield. If it be broken, Ireland will go down. They may well throw themselves heartily into the common defense, for no sword can transfix England without the point reaching Ireland behind her." However The Irish Review author proposes to show that "Ireland, far from sharing the calamities that must necessarily fall on Great Britain from defeat by a Great Power, might conceivably thereby emerge into a position of much prosperity." The contents page of the July 1913 issue of The Irish Review In supporting this provocative stance the author initially tackles two aspects of the accepted British view of Ireland's fate under these circumstances: that Ireland would remain tied with Britain under German rule or that she might be annexed by the victor. -

James Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Stephens(9 February 1882 - 26 December 1950) James Stephens was an Irish novelist and poet. James Stephens produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humor and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praise). He also wrote several original novels (Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. "Crock of Gold," in particular, achieved enduring popularity and was reprinted frequently throughout the author's lifetime. Stephens began his career as a poet with the tutelage of "Æ" (<a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-william-a-e-russell-2/">George William Russel</a>l). His first book of poems, "Insurrections," was published during 1909. His last book, "Kings and the Moon" (1938), was also a volume of verse. During the 1930s, Stephens had some acquaintance with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/james-joyce/">James Joyce</a>, who found that they shared a birth year (and, Joyce mistakenly believed, a birthday). Joyce, who was concerned with his ability to finish what later became Finnegans Wake, proposed that Stephens assist him, with the authorship credited to JJ & S (James Joyce & Stephens, also a pun for the popular Irish whiskey made by John Jameson & Sons). The plan, however, was never implemented, as Joyce was able to complete the work on his own. During the last decade of his life, Stephens found a new audience through a series of broadcasts on the BBC. -

James Stephens at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 5 Issue 9 March Article 5 March 1961 James Stephens at Colby College Richard Cary. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 5, no.9, March 1961, p.224-253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cary.: James Stephens at Colby College 224 Colby Library Quarterly shadow and symbolize death: the ship sailing to the North Pole is the Vehicle of Death, and the captain of the ship is Death himself. Stephens here makes use of traditional motifs. for the purpose of creating a psychological study. These stories are no doubt an attempt at something quite distinct from what actually came to absorb his mind - Irish saga material. It may to my mind be regretted that he did not write more short stories of the same kind as the ones in Etched in Moonlight, the most poignant of which is "Hunger," a starvation story, the tragedy of which is intensified by the lucid, objective style. Unfortunately the scope of this article does not allow a treat ment of the rest of Stephens' work, which I hope to discuss in another essay. I have here dealt with some aspects of the two middle periods of his career, and tried to give significant glimpses of his life in Paris, and his .subsequent years in Dublin. In 1915 he left wartime Paris to return to a revolutionary Dub lin, and in 1925 he left an Ireland suffering from the after effects of the Civil War. -

The George Russell Collection at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 4 Issue 2 May Article 6 May 1955 The George Russell Collection at Colby College Carlin T. Kindilien Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 4, no.2, May 1955, p.31-55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kindilien: The George Russell Collection at Colby College Colby Library Quarterly 3 1 acted like a lot of bad boys in their conversation with each other but they did it in beautiful English. I never knew AE to tell a story which was in the slightest degree off color or irreverent. And yet, of an evening, he could grip your closest attention as you listened steadily to an endless flow of words from nine in the evening till two in the morn ing. In 1934 Mary Rumsey offered to pay AE's expenses to come to this country to consult with the Department of Agriculture. Robert Frost was somewhat annoyed because he felt we should have called him in rather than AE. At the moment, however, AE, when talking to our Exten sion people, furnished a type of profound inspiration which I thought was exceedingly important. He worked largely out of the office of M. L. Wilson, who later became Under-Secretary of Agriculture and Director of Extension. In this period I had him out to our apartment with Justice Stone, the Morgenthaus, and others. -

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival Author: Dathalinn Mary O'Dea Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104356 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of English THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL a dissertation by DATHALINN M. O’DEA submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 © copyright by DATHALINN M. O’DEA 2014 Abstract THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL Director: Dr. Marjorie Howes, Boston College Readers: Dr. Paige Reynolds, College of the Holy Cross and Dr. Christopher Wilson, Boston College This study examines how Irish and American writing from the early twentieth century demonstrates a continued engagement with the formal, thematic and cultural imperatives of the Irish Literary Revival. It brings together writers and intellectuals from across Ireland and the United States – including James Joyce, George William Russell (Æ), Alice Milligan, Lewis Purcell, Lady Gregory, the Fugitive-Agrarian poets, W. B. Yeats, Harriet Monroe, Alice Corbin Henderson, and Ezra Pound – whose work registers the movement’s impact via imitation, homage, adaptation, appropriation, repudiation or some combination of these practices. Individual chapters read Irish and American writing from the period in the little magazines and literary journals where it first appeared, using these publications to give a material form to the larger, cross-national web of ideas and readers that linked distant regions. -

Autochthons and Otherworlds in Celtic and Slavic

Grigory Bondarenko Coleraine Address AUTOCHTHONS AND OTHERWORLDS IN CELTIC AND SLAVIC 1. Introduction. Separation of Ireland in Mesca Ulad. When dealing with Irish Otherworld one encounters the problem of the beginning of historical consciousness in Ireland. The time immemorial when the Túatha Dé were said to have ruled Ireland as described in the first half of ‘The Wooing of Etaín’ (Tochmarc Etaíne) is perceived as a period during which there is no sharp division between this world and the Otherworld, nor between sons of Míl and the Tuatha Dé, the time when gods walked on earth (Bergin, Best 1934–38: 142–46).1 One can even argue that even in the later periods (according to Irish traditional chronology), as they are reflected in early Irish tradition, the border-line between this world and the ‘supernatural’ existence is transparent and in any relevant early Irish narrative one can hardly trace a precise moment when a hero enters the ‘Otherworld’. What is remarkable is that one can definitely detect ‘other- worldly’ characters in this environment such as the supernatural beings (áes síde) that are associated with a particular locus, a síd. The seemingly ‘historical’ question of when lower Otherworld in Ireland was first separat- ed from the middle world of humans is dealt with in a number of early Irish tales. Let us focus on a short fragment from an Ulster cycle tale ‘The drunk- enness of the Ulaid’ (Mesca Ulad). The problem of áes síde and their oppo- sition to humans is posed here only in order to determine the conflict in the tale. -

Leeds Studies in English

Leeds Studies in English Article: Bernard K. Martin, '"Truth' and 'Modesty": A Reading of the Irish Noinden Ulad', Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 20 (1989), 99-117 Permanent URL: https://ludos.leeds.ac.uk:443/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=123705&silo_library=GEN01 Leeds Studies in English School of English University of Leeds http://www.leeds.ac.uk/lse 'Truth' and 'Modesty': A Reading of the Irish Noinden Ulad B. K. Martin The Cattle-Raid ofCooley, or Tain Bo Cuailnge, is the most ambitious narrative in the medieval Irish Ulster Cycle, but its basic plot is quite simple.1 Ailill and Medb, rulers of Connacht, lead a great plundering raid against the neighbouring province of Ulster, where Conchobar is king. At the hour of crisis Ulster has virtually only one defender, CuChulainn: for some three months, and almost single-handed, CuChulainn harasses and delays the invaders by fighting and negotiating and manipulating the 'rules' of heroic warfare. Then at last the hosts of Ulster arise and come to drive the invaders away. But why must CuChulainn defend his people for so long alone? It is not difficult to answer: because the warriors of Ulster have been stricken with their 'debility' (noinden, or ces(s)). This has left them as weak as a woman who has just given birth. This collective debility was one which did not affect females nor ungrown boys nor CuChulainn; and because it incapacitated his fellow-warriors it made CuChulainn's heroic feats in the Tain seem all the more brilliant. It is a puzzling debility, and is not very clearly described. -

The Names and Epithets of the Dagda

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-04 The Names and Epithets of the Dagda Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138966 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository The Names and Epithets of the Dagda Scott A. Martin, April 2012 Aed Abaid Essa Ruaid misi .i. dagdia druidechta Tuath De Danann 7 in Ruad Rofhessa 7 Eochaid Ollathair mo tri hanmanna. “I am Aed Abaid of Ess Rúaid, that is, the Good God of wizardry of the Túatha Dé Danann, and the Rúad Rofhessa, and Eochaid Ollathair are my three names.” (Bergin 1927) This opening line from “How the Dagda Got His Magic Staff” neatly summarizes the names by which the Dagda is known in the surviving Irish manuscripts. Translations for these names begin to shed some light on the character of this deity: the “Good God,” the “Red/Mighty One of Great Knowledge,” and “Horseman Great-father.” What other information can be gleaned about the Dagda from the way in which he is named? This essay will examine the descriptions and appellations attached to the Dagda in various texts in an attempt to provide some further answers to this question. It should be emphasized at the outset that the conclusions below are intended to enrich our religious, rather than scholarly, understanding of the Dagda, and that some latitude should be afforded the interpretations on this basis. The glossary Cóir Anmann (The Fitness of Names) contains adjacent entries for the Dagda under each of his three names (Stokes 1897: 354-357): 150. -

![Cll Roi and SVYATOGOR: a STUDY in CHTHONIC 1986: 52]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2196/cll-roi-and-svyatogor-a-study-in-chthonic-1986-52-2662196.webp)

Cll Roi and SVYATOGOR: a STUDY in CHTHONIC 1986: 52]

Grigory Bondarenko 65 tIe field made by Cll RQf. It makes him a character closely similar tQ Russian Svya• tQgor whQm we meet quite .often 'in a clear field' (vo chistom, vo poli) [PutiIQV Cll Roi AND SVYATOGOR: A STUDY IN CHTHONIC 1986: 52]. Polye 'field, plain, steppe' is the mQst suitable place fQr the heroes .of GRIGORY BONDARENKO Russian bylinas tQ meet each .other, tQ exchange herQic feats, tQ fight their enemies and tQ fight each .other. The topos .of the 'field' is CQmmQnbQth fQr Russian and for O.Introduction Iris,h herQic epics. At the same time 'field' dQes nQt cQnstitute a proper IQCUSfQr Cll RQI and SvyatQgQr. It IS merely an .outer space for their adventures. BQth Early Irish and Russian mythQIQgical traditiQns demQnstrate a particular The meaning .of roe discussed befQre was accepted by Rhys, Meyer, d' ArbQis, example .of an extraQrdinary character shQwing sup~rnatural features as well as the and Stokes. However T. F. O'Rahilly has argued against this view .on the basis .of features .of a chthQnic mQnster: it is Cli RQf mac Dmre .on the Insh slde, and Svya• the ~arlier fQrm ~uRaui; taking or gen . .of roe 'plain' tQ be roe (disyllabic). Ac• tQgQr .on the Russian side. We have tQ be careful before arguing that these tw.Q cQrdmg tQ.~'RahJ1ly, gen. Raul< Ravios 'roarer?' (a theonym?) (O'Rahilly 1946: mythQIQgical characters reflect .one particular archetype .of a mQnstrQUS chthQmc 5-6], that 1S the Hound of the RQarer-god?' It shQuld be stressed here that the name creature (cf.