Parody in James Stephens's Deirdre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes

ffVJU*S )UjfáZt ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV KUNO MEYER, Ph.D. THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO. LTD. LONDON: WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 (Reprinted 1937) cJ&íc+u. Ity* rs** "** ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV. KUNO MEYER THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO., Ltd, LONDON : WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 °* s^ B ^N Made and Printed by the Replika Process in Great Britain by PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES &f CO. LTD. 1 2 Bedford Square, London, W.C. i and at Bradford CONTENTS PAGE Peeface, ....... v-vii I. The Death of Conchobar, 2 II. The Death of Lóegaire Búadach . 22 III. The Death of Celtchar mac Uthechaib, 24 IV. The Death of Fergus mac Róich, . 32 V. The Death of Cet mac Magach, 36 Notes, ........ 48 Index Nominum, . ... 46 Index Locorum, . 47 Glossary, ....... 48 PREFACE It is a remarkable accident that, except in one instance, so very- few copies of the death-tales of the chief warriors attached to King Conchobar's court at Emain Macha should have come down to us. Indeed, if it were not for one comparatively late manu- script now preserved outside Ireland, in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh, we should have to rely for our knowledge of most of these stories almost entirely on Keating's History of Ireland. Under these circumstances it has seemed to me that I could hardly render a better service to Irish studies than to preserve these stories, by transcribing and publishing them, from the accidents and the natural decay to which they are exposed as long as they exist in a single manuscript copy only. -

Making Fenians: the Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876 Timothy Richard Dougherty Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, Timothy Richard, "Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 143. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the constitutive rhetorical strategies of revolutionary Irish nationalists operating transnationally from 1858-1876. Collectively known as the Fenians, they consisted of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the United Kingdom and the Fenian Brotherhood in North America. Conceptually grounded in the main schools of Burkean constitutive rhetoric, it examines public and private letters, speeches, Constitutions, Convention Proceedings, published propaganda, and newspaper arguments of the Fenian counterpublic. It argues two main points. First, the separate national constraints imposed by England and the United States necessitated discursive and non- discursive rhetorical responses in each locale that made -

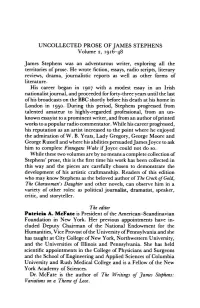

UNCOLLECTED PROSE of JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48

UNCOLLECTED PROSE OF JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48 James Stephens was an adventurous writer, exploring all the territories of prose. He wrote fiction, essays, radio scripts, literary reviews, drama, journalistic reports as well as other forms of literature. His career began in 1907 with a modest essay in an Irish nationalist journal, and proceeded for forty-three years until the last of his broadcasts on the BBC shortly before his death at his home in London in 1950. During this period, Stephens progressed from talented amateur to highly-regarded professional, from an un known essayist to a prominent writer, and from an author of printed works to a popular radio commentator. While his career progi-essed, his reputation as an artist increased to the point where he enjoyed the admiration ofW. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Moore and George Russell and where his abilities persuaded James Joyce to ask him to complete Finnegans Wake if Joyce could not do so. While these two volumes are by no means a complete collection of Stephens' prose, this is the first time his work has been collected in this way and the pieces are carefully chosen to demonstrate the development of his artistic craftmanship. Readers of this edition who may know Stephens as the beloved author of The Crock oJGold, The Charwoman's Daughter and other novels, can observe him in a variety of other roles: as political journalist, dramatist, speaker, critic, and storyteller. The editor Patricia A. McFate is President of the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York. Her previous appointments have in cluded Deputy Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vice Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and she has taught at City College of New York, Northwestern University, and the Universities of Illinois and Pennsylvania. -

Irish Identity in the Union Army During the American Civil War Brennan Macdonald Virginia Military Institute

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Ninth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2018 “A Country in Their eH arts”: Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War Brennan MacDonald Virginia Military Institute Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush MacDonald, Brennan, "“A Country in Their eH arts”: Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War" (2018). MAD- RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2018/civilwar/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 MacDonald BA Virginia Military Institute “A Country in Their Hearts” Irish Identity in the Union Army during the American Civil War 2 Immigrants have played a role in the military history of the United States since its inception. One of the most broadly studied and written on eras of immigrant involvement in American military history is Irish immigrant service in the Union army during the American Civil War. Historians have disputed the exact number of Irish immigrants that donned the Union blue, with Susannah Ural stating nearly 150,000.1 Irish service in the Union army has evoked dozens of books and articles discussing the causes and motivations that inspired these thousands of immigrants to take up arms. In her book, The Harp and the Eagle: Irish American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865, Susannah Ural attributes Irish and specifically Irish Catholic service to “Dual loyalties to Ireland and America.”2 The notion of dual loyalty is fundamental to understand Irish involvement, but to take a closer look is to understand the true sense of Irish identity during the Civil War and how it manifested itself. -

James Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Stephens(9 February 1882 - 26 December 1950) James Stephens was an Irish novelist and poet. James Stephens produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humor and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praise). He also wrote several original novels (Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. "Crock of Gold," in particular, achieved enduring popularity and was reprinted frequently throughout the author's lifetime. Stephens began his career as a poet with the tutelage of "Æ" (<a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-william-a-e-russell-2/">George William Russel</a>l). His first book of poems, "Insurrections," was published during 1909. His last book, "Kings and the Moon" (1938), was also a volume of verse. During the 1930s, Stephens had some acquaintance with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/james-joyce/">James Joyce</a>, who found that they shared a birth year (and, Joyce mistakenly believed, a birthday). Joyce, who was concerned with his ability to finish what later became Finnegans Wake, proposed that Stephens assist him, with the authorship credited to JJ & S (James Joyce & Stephens, also a pun for the popular Irish whiskey made by John Jameson & Sons). The plan, however, was never implemented, as Joyce was able to complete the work on his own. During the last decade of his life, Stephens found a new audience through a series of broadcasts on the BBC. -

Yeats and the Mask of Deirdre: "That Love Is All We Need"

Colby Quarterly Volume 37 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 2001 Yeats and the Mask of Deirdre: "That love is all we need" Maneck H. Daruwala Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 37, no.3, September 2001, p.247-266 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Daruwala: Yeats and the Mask of Deirdre: "That love is all we need" Yeats and the Mask ofDeirdre: "That love is all we need II By MANECK H. DARUWALA The poet finds and makes his mask in disappointment, the hero in defeat. The desire that can be satisfied is not a great desire. (Yeats) Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth. (Wilde) EIRDRE, written during a very painful period of Yeats's life, is a civilized D form of autobiography. What could not be put down in journals or lyric poetry and could not be ignored becomes drama. Yeats turns here from the mirror to the mask. "The poet finds and makes his mask in disappointment, the hero in defeat" ("Anima Hominis," Mythologies, 334, 337), may apply equally to Yeats and Naoise. As Yeats says, there is always a phantasmago ria. Here the phantasmagoria includes Celtic myth, politics, chess games, and the literary tradition (or intertextuality-which, like a Greek mask, combines the advantages of resonance with those of disguise). -

The Wooing of Emer and Other Stories

The Ulster Cycle: The Wooing of Emer and other stories by Patrick Brown The fullest version of The Wooing of Emer is found in the Book of Leinster (c.1160) in a text dating from the tenth or eleventh century. An earlier, fragmentary version is found in several manuscripts, including Lebor na hUidre (the Book of the Dun Cow, c.1106). This retelling is based on both versions. Cú Chulainn’s Shield is an anecdote found in the manuscript H.3.17. This is my own translation, with thanks to Breandán Dalton, Dennis King, and especially David Stifter for their help and suggestions. The Death of Aífe’s Only Son is found in the Yellow Book of Lecan, compiled about 1390, but the language of the story dates from the ninth or tenth century. The Death of Derbforgaill is found in the Book of Leinster. The Elopement of Emer comes from the late 14th Century Stowe MS No 992. The Training of Cú Chulainn is a late, alternative version of Cú Chulainn’s travels and training. It is found in no less than eleven different manuscripts, the earliest being Egerton 106, dated to 1715. The Ulster Cycle: The Wooing of Emer and other stories © Patrick Brown 2002/2008 The Wooing of Emer A great and famous king, Conchobor son of Fachtna Fathach, once ruled in Emain Macha, and his reign was one of peace and prosperity and abundance and order. His house, the Red Branch, built in the likeness of the Tech Midchuarta in Tara, was very impressive, with nine compartments from the fire to the wall, separated by thirty-foot-high bronze partitions. -

James Stephens at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 5 Issue 9 March Article 5 March 1961 James Stephens at Colby College Richard Cary. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 5, no.9, March 1961, p.224-253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cary.: James Stephens at Colby College 224 Colby Library Quarterly shadow and symbolize death: the ship sailing to the North Pole is the Vehicle of Death, and the captain of the ship is Death himself. Stephens here makes use of traditional motifs. for the purpose of creating a psychological study. These stories are no doubt an attempt at something quite distinct from what actually came to absorb his mind - Irish saga material. It may to my mind be regretted that he did not write more short stories of the same kind as the ones in Etched in Moonlight, the most poignant of which is "Hunger," a starvation story, the tragedy of which is intensified by the lucid, objective style. Unfortunately the scope of this article does not allow a treat ment of the rest of Stephens' work, which I hope to discuss in another essay. I have here dealt with some aspects of the two middle periods of his career, and tried to give significant glimpses of his life in Paris, and his .subsequent years in Dublin. In 1915 he left wartime Paris to return to a revolutionary Dub lin, and in 1925 he left an Ireland suffering from the after effects of the Civil War. -

Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 The aW rped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, M. J.(2019). The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5278 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth By Martha J. Lee Bachelor of Business Administration University of Georgia, 1995 Master of Arts Georgia Southern University, 2003 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Ed Madden, Major Professor Scott Gwara, Committee Member Thomas Rice, Committee Member Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Martha J. Lee, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation and degree belong as much or more to my family as to me. They sacrificed so much while I traveled and studied; they supported me, loved and believed in me, fed me, and made sure I had the time and energy to complete the work. My cousins Monk and Carolyn Phifer gave me a home as well as love and support, so that I could complete my course work in Columbia. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

1 Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend Irish Mythology Has Been

Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend u u Irish mythology has been classified or taxonomized into four cycles (collections, sets) • From the oldest tales to the most recent, they are: the Mythological Cycle; the Ulster (or Red Branch) Cycle; the Fenian (or Ossianic) Cycle; and the Historical (or Kings') Cycle u u The Mythological Cycle is dominated by origin myths called pseudohistories • These tales narrate a series of foreign invasions of Ireland, with each new wave of invader-settlers marginalizing the formerly dominant group u The oldest group, the Fomorians, resemble the Greek Titans: semi-divine beings associated with the chaos that preceded the civilizing gods u The penultimate aggressor group, the Tuatha Dé Danann (people of the goddess Danu), suffered defeat at the hands of the Milesians or Gaels, who entered Ireland from northern Spain • Legendarily, some surviving members of the Tuatha Dé Danann became the fairies or "little people," occupying aerial or subterranean (underground) zones on the island of Ireland but with a different temporality • The Irish author C.S. Lewis uses this idea in his Narnia series, where the portal into Narnia—a place outside "regular' time—is a wardrobe u Might the Milesians have, in fact, come from Spain? • A March 2000 article in the esteemed science journal Nature revealed that 98% of Connacht (west-of-Ireland) men and 89% of Basque (northeast-of- Spain) men carry the ancestral (or hunter-gatherer) European DNA signature, which passes from father to son • By contrast with the high Irish and -

The George Russell Collection at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 4 Issue 2 May Article 6 May 1955 The George Russell Collection at Colby College Carlin T. Kindilien Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 4, no.2, May 1955, p.31-55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kindilien: The George Russell Collection at Colby College Colby Library Quarterly 3 1 acted like a lot of bad boys in their conversation with each other but they did it in beautiful English. I never knew AE to tell a story which was in the slightest degree off color or irreverent. And yet, of an evening, he could grip your closest attention as you listened steadily to an endless flow of words from nine in the evening till two in the morn ing. In 1934 Mary Rumsey offered to pay AE's expenses to come to this country to consult with the Department of Agriculture. Robert Frost was somewhat annoyed because he felt we should have called him in rather than AE. At the moment, however, AE, when talking to our Exten sion people, furnished a type of profound inspiration which I thought was exceedingly important. He worked largely out of the office of M. L. Wilson, who later became Under-Secretary of Agriculture and Director of Extension. In this period I had him out to our apartment with Justice Stone, the Morgenthaus, and others.