Volume 12, Issue 2 May 2014 Ability Privilege: a Needed Addition To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(In)Ing the Other in the Digital Turn

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 8.1. | 2020 Ubiquitous Visuality Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.1957 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Diane Leblond, “Ways of Seeing Animals”, InMedia [Online], 8.1. | 2020, Online since 15 December 2020, connection on 26 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.1957 This text was automatically generated on 26 January 2021. © InMedia Ways of Seeing Animals 1 Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Introduction. Looking at animals: when visual nature questions visual culture 1 A topos of Western philosophy indexes animals’ irreducible alienation from the human condition on their lack of speech. In ancient times, their inarticulate cries provided the necessary analogy to designate non-Greeks as other, the adjective “Barbarian” assimilating foreign languages to incomprehensible birdcalls.1 To this day, the exclusion of animals from the sphere of logos remains one of the crucial questions addressed by philosophy and linguistics.2 In the work of some contemporary critics, however, the tenets of this relation to the animal “other” seem to have undergone a change in focus. With renewed insistence that difference is inextricably bound up in a sense of proximity, such writings have described animals not simply as “other,” but as our speechless others. This approach seems to find particularly fruitful ground where theory proposes to explore ways of seeing as constitutive of the discursive structures that we inhabit. -

Critical Animal Studies: an Introduction by Dawne Mccance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto

The Goose Volume 13 | No. 1 Article 25 8-1-2014 Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Collard, Rosemary-Claire. "Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance." The Goose, vol. 13 , no. 1 , article 25, 2014, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol13/iss1/25. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Collard: Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Made, not born, machines this reduction is accomplished and what its implications are for animal life and Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction death. by DAWNE McCANCE After a short introduction in State U of New York P, 2013 $22.65 which McCance outlines the hierarchical Cartesian dualism (mind/body, Reviewed by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE human/animal) to which her book and COLLARD critical animal studies’ are opposed, McCance turns to what are, for CAS The field of critical animal scholars, familiar figures in a familiar studies (CAS) is thoroughly multi- place: Peter Singer and Tom Regan on disciplinary and, as Dawne McCance’s the factory farm. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in Society, Culture and the Media

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in society, culture and the media List of readings Approved by the board of the Department of Communication and Media 2019-12-03 Introduction to the critical study of human-animal relations Adams, Carol J. (2009). Post-Meateating. In T. Tyler and M. Rossini (Eds.), Animal Encounters Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 47-72. Emel, Jody & Wolch, Jennifer (1998). Witnessing the Animal Moment. In J. Wolch & J. Emel (Eds.), Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature- Culture Borderlands. London & New York: Verso pp. 1-24 LeGuin, Ursula K. (1988). ’She Unnames them’, In Ursula K. LeGuin Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences. New York, N.Y.: New American Library. pp. 1-3 Nocella II, Anthony J., Sorenson, John, Socha, Kim & Matsuoka, Atsuko (2014). The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of Intersectional Animal Liberation. In A.J. Nocella II, J. Sorenson, K. Socha & A. Matsuoka (Eds.), Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation. New York: Peter Lang. pp. xix-xxxvi Salt, Henry S. (1914). Logic of the Larder. In H.S. Salt, The Humanities of Diet. Manchester: Sociey. 3 pp. Sanbonmatsu, John (2011). Introduction. In J. Sanbonmatsu (Ed.), Critical Theory and Animal Liberation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1-12 + 20-26 Stanescu, Vasile & Twine, Richard (2012). ‘Post-Animal Studies: The Future(s) of Critical Animal Studies’, Journal of Critical Animal Studies 10(2), pp. 4-19. Taylor, Sunara. (2014). ‘Animal Crips’, Journal for Critical Animal Studies. 12(2), pp. 95-117. /127 pages Social constructions, positions, and representations of animals Arluke, Arnold & Sanders, Clinton R. -

Centre for the Study of Social and Political

CENTRE FOR THE STUDY ABOUT OF SOCIAL AND The Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements was established in 1992, and since then has helped the University of Kent gain wider POLITICAL recognition as a leading institution in the study of social and political movements in the UK. The Centre has attracted research council, European Union, and charitable foundation funding, and MOVEMENTS collaborated with international partners on major funding projects. Former staff members and external associates include Professors Mario Diani, Frank Furedi, Dieter Rucht, and Clare Saunders. Spri ng 202 1 Today, the Centre continues to attract graduate students and international visitors, and facilitate the development of collaborative research. Dear colleagues, Recent and ongoing research undertaken by members includes studies of Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, veganism and animal rights. Things have been a bit quiet in the center this year as we’ve been teaching online and unable to meet in person. That said, social The Centre takes a methodologically pluralistic movements have not been phased by the pandemic. In the US, Black and interdisciplinary approach, embracing any Lives Matter protests trudge on, fueled by the recent conviction of topic relevant to the study of social and political th movements. If you have any inquiries about George Floyd’s murder on April 20 and the police killing of 16 year old Centre events or activities, or are interested in Ma'Khia Bryant in Ohio that same day. Meanwhile, the killing of Kent applying for our PhD programme, please contact resident Sarah Everard (also by a police officer) spurred considerable Dr Alexander Hensby or Dr Corey Wrenn. -

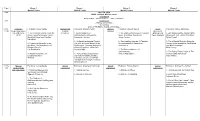

2010 Schedule Chart (8 1/2 X 14 In

Time Room 1. Room 2. Room 3. Room 4. Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center 9:00 April 10, 2010 SUNY Cortland, Moffett Center Registration Sarat Colling - Elizabeth Green – Ashley Mosgrove 9:30 Introduction Anthony J. Nocella, II Welcoming Andrew Fitz-Gibbon and Mechthild Nagel 10:00 – Academic Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animals and Facilitator: Ronald Pleban Species Facilitator: Doreen Nieves Social Facilitator: Ashley Mosgrove 11:20 Repression Book Cultural Inclusion Movement Talk (AK Press, 1. The Carceral Society: From the Practices 1 Animal Subjects in 1. The Politics of Inclusion: A Feminist Strategy and 1. DIY Media and the Animal Rights 2010) Prison Tower to the Ivory Tower Anthropological Perspective Space to Critique Speciesism Tactic Analysis Movement: Talk - Action = Nothing Mechthild Nagel and Caroline Alessandro Arrigoni Jenny Grubbs Dylan Powell Kaltefleiter 2. An American Imperial Project: 2. Transcending Species: A Feminist 2. The Influential Activist: Using the 2. Regimes of Normalcy in the The Role of Animal Bodies in the Re-examination of Oppression Science of Persuasion to Open Minds Academy: The Experiences of Smithsonian-Theodore Roosevelt Jeni Haines and Win Campaigns Disabled Faculty African Expedition, 1909-1910. Nick Cooney Liat Ben-Moshe Laura Shields 3. The Reasonableness of Sentimentality 3. The Role of Direct Action in The 3. Adelphi Recovers „The 3. Conservation perspectives: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon Animal Rights Movement Lengthening View International wildlife priorities, Carol Glasser Ali Zaidi individual animals, and wildlife management strategies in Kenya Stella Capoccia 11:30- Species Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animal Facilitator: Anastasia Yarbrough Animal Facilitator: Brittani Mannix Animal Facilitator: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon 1:00 Relationships Exploitation Exploitation Exploitation and Domination 1. -

Journal for Critical Animal Studies

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies Special issue Inquiries and Intersections: Queer Theory and Anti-Speciesist Praxis Guest Editor: Jennifer Grubbs 1 ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD GUEST EDITOR Jennifer Grubbs [email protected] ISSUE EDITOR Dr. Richard J White [email protected] EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE Dr. Matthew Cole [email protected] Vasile Stanescu [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas [email protected] Dr. Richard Twine [email protected] Dr. Richard J White [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Lindgren Johnson [email protected] Laura Shields [email protected] FILM REVIEW EDITORS Dr. Carol Glasser [email protected] Adam Weitzenfeld [email protected] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For more information about the JCAS Editorial Board, and a list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board, please visit the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 2 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD ............................................................................................................. 2 GUEST EDITORIAL .............................................................................................................. 4 ESSAYS From Beastly Perversions to the Zoological Closet: Animals, Nature, and Homosex Jovian Parry ............................................................................................................................. -

The Covid Pandemic, 'Pivotal' Moments, And

Animal Studies Journal Volume 10 Number 1 Article 10 2021 The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives Paula Arcari Edge Hill University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Arcari, Paula, The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives, Animal Studies Journal, 10(1), 2021, 186-239. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol10/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives Abstract Situated alongside, and intertwined with, climate change and the relentless destruction of ‘wild’ nature, the global Covid-19 pandemic should have instigated serious reflection on our profligate use and careless treatment of other animals. Widespread references to ‘pivotal moments’ and the need for a reset in human relations with ‘nature’ appeared promising. However, important questions surrounding the pandemic’s origins and its wider context continue to be ignored and, as a result, this moment has proved anything but pivotal for animals. To explore this disconnect, this paper undertakes an analysis of dominant Covid discourses across key knowledge sites comprising mainstream media, major organizations, academia, and including prominent animal advocacy organizations. Drawing on the core tenets of Critical Animal Studies, the concept of critical animal perspectives is advanced as a way to assess these discourses and explore the illegitimacy of alternative ways of thinking about animals. -

CRITICAL TERMS for ANIMAL STUDIES

CRITICAL TERMS for ANIMAL STUDIES Edited by LORI GRUEN THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago and London Contents Introduction • Lori Gruen 1 1 Abolition • Claire Jean Kim 15 2 Activism • Jeff Sebo and Peter Singer 33 3 Anthropocentrism • Fiona Probyn- Rapsey 47 4 Behavior • Alexandra Horowitz 64 5 Biopolitics • Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel 79 6 Captivity • Lori Marino 99 7 Difference • Kari Weil 112 8 Emotion • Barbara J. King 125 9 Empathy • Lori Gruen 141 10 Ethics • Alice Crary 154 11 Extinction • Thom van Dooren 169 12 Kinship • Agustín Fuentes and Natalie Porter 182 13 Law • Kristen Stilt 197 14 Life • Eduardo Kohn 210 15 Matter • James K. Stanescu 222 16 Mind • Kristin Andrews 234 17 Pain • Victoria A. Braithwaite 251 18 Personhood • Colin Dayan 267 19 Postcolonial • Maneesha Deckha 280 20 Rationality • Christine M. Korsgaard 294 21 Representation • Robert R. McKay 307 22 Rights • Will Kymlicka and Sue Donaldson 320 23 Sanctuary • Timothy Pachirat 337 24 Sentience • Gary Varner 356 25 Sociality • Cynthia Willett and Malini Suchak 370 26 Species • Harriet Ritvo 383 27 Vegan • Annie Potts and Philip Armstrong 395 28 Vulnerability • Anat Pick 410 29 Welfare • Clare Palmer and Peter Sandøe 424 Acknowledgments 439 List of Contributors 441 Index 451 INTRODUCTION Lori Gruen Animal Studies is almost always described as a new, emerging, and growing field. A short while ago some Animal Studies scholars suggested that it “has a way to go before it can clearly see itself as an academic field” (Gorman 2012). Other scholars suggest that the “discipline” is a couple of decades old (DeMello 2012). -

Animal Bodies, Colonial Subjects: (Re)Locating Animality in Decolonial Thought

Societies 2015, 5, 1–11; doi:10.3390/soc5010001 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article Animal Bodies, Colonial Subjects: (Re)Locating Animality in Decolonial Thought Billy-Ray Belcourt Department of Modern Languages and Cultural Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2R3, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-780-536-7508 Academic Editor: Chloë Taylor Received: 10 November 2014 / Accepted: 23 December 2014 / Published: 24 December 2014 Abstract: In this paper, I argue that animal domestication, speciesism, and other modern human-animal interactions in North America are possible because of and through the erasure of Indigenous bodies and the emptying of Indigenous lands for settler-colonial expansion. That is, we cannot address animal oppression or talk about animal liberation without naming and subsequently dismantling settler colonialism and white supremacy as political machinations that require the simultaneous exploitation and/or erasure of animal and Indigenous bodies. I begin by re-framing animality as a politics of space to suggest that animal bodies are made intelligible in the settler imagination on stolen, colonized, and re-settled Indigenous lands. Thinking through Andrea Smith’s logics of white supremacy, I then re-center anthropocentrism as a racialized and speciesist site of settler coloniality to re-orient decolonial thought toward animality. To critique the ways in which Indigenous bodies and epistemologies are at stake in neoliberal re-figurings of animals as settler citizens, I reject the colonial politics of recognition developed in Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka’s recent monograph, Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights (Oxford University Press 2011) because it militarizes settler-colonial infrastructures of subjecthood and governmentality. -

Volume 15, Issue 5, 2018

Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 15, Issue 5, 2018 1 Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Journal for Critical Animal Studies _____________________________________________________________________________ Editor Dr. Amber E. George [email protected] Submission Peer Reviewers Michael Anderson Dr. Stephen R. Kauffman Drew University Christian Vegetarian Association Dr. Julie Andrzejewski Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II St. Cloud State University Independent Scholar Mandy Bunten-Walberg Dr. Emily Patterson-Kane Independent Scholar American Veterinary Medical Association Sarat Colling Dr. Nancy M. Rourke Independent Scholar Canisius College Dr. Tara Cornelisse N. T. Rowan Center for Biological Diversity York University Stephanie Eccles Nicole Sarkisian Concordia University SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Adam J. Fix SUNY College of Environmental Science Tayler E. Staneff and Forestry University of Victoria Dr. Carrie P. Freeman Dr. Gina M. Sully Georgia State University University of Las Vegas Dr. Cathy B. Glenn Dr. Siobhan Thomas Independent Scholar London South Bank University David Gould Tyler Tully University of Leeds University of Oxford Krista Hiddema Dr. Richard White Royal Roads University Sheffield Hallam University William Huggins Dr. Rulon Wood Independent Scholar Boise State University i Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Cover Art: Muller, A. (2015, August 27). Vegetarian street sign. CC0 Creative Commons. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/alexander_mueller_photolover/ -

Animal-Industrial Complex‟ – a Concept & Method for Critical Animal Studies? Richard Twine

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 EDITORAL BOARD Dr. Richard J White Chief Editor [email protected] Dr. Nicole Pallotta Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Lindgren Johnson Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Laura Shields Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Richard Twine Book Review Editor [email protected] Vasile Stanescu Book Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Carol Glasser Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Adam Weitzenfeld Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Cole Web Manager [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For a complete list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board please see the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 1 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 EDITORAL BOARD ..............................................................................................................