Critical Animal Studies and Animal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus Animal Studies: an Introduction ANTH S-1625 Harvard Summer School 2016 Dr

2016.6.10 draft Course Syllabus Animal Studies: An Introduction ANTH S-1625 Harvard Summer School 2016 Dr. Paul Waldau Course Description This course traces the history and shape of academic efforts to study nonhuman animals. Animal studies scholars explore such questions as, how do contemporary Western societies characterize the differences between humans and non-human animals? What ethical debates surround the use of animals in scientific research or the use of animals for food? How different are other cultures’ views of nonhuman animals from the views that now prevail in the United States and other early twenty-first century industrialized societies? What assumptions in educational systems have fostered the study of nonhuman animals, and what assumptions of specific educational systems have hampered such study? Class sessions are discussion-based, and students undertake group work, significant writing, and an individual presentation. In addition, note carefully each of the Learning Objectives listed below. We will discuss these objectives regularly through significant writing, group-based discussion and individual presentations that explore the interdisciplinary implications of weaving together the humanities with sciences (both social and natural). There are no prerequisites for this course. Required Readings and Course Materials • Waldau, Paul 2013. Animal Studies: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press • Additional Course Materials will be specified, and most of them will be available online or in .pdf format at the -

Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(In)Ing the Other in the Digital Turn

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 8.1. | 2020 Ubiquitous Visuality Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.1957 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Diane Leblond, “Ways of Seeing Animals”, InMedia [Online], 8.1. | 2020, Online since 15 December 2020, connection on 26 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.1957 This text was automatically generated on 26 January 2021. © InMedia Ways of Seeing Animals 1 Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Introduction. Looking at animals: when visual nature questions visual culture 1 A topos of Western philosophy indexes animals’ irreducible alienation from the human condition on their lack of speech. In ancient times, their inarticulate cries provided the necessary analogy to designate non-Greeks as other, the adjective “Barbarian” assimilating foreign languages to incomprehensible birdcalls.1 To this day, the exclusion of animals from the sphere of logos remains one of the crucial questions addressed by philosophy and linguistics.2 In the work of some contemporary critics, however, the tenets of this relation to the animal “other” seem to have undergone a change in focus. With renewed insistence that difference is inextricably bound up in a sense of proximity, such writings have described animals not simply as “other,” but as our speechless others. This approach seems to find particularly fruitful ground where theory proposes to explore ways of seeing as constitutive of the discursive structures that we inhabit. -

Critical Animal Studies: an Introduction by Dawne Mccance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto

The Goose Volume 13 | No. 1 Article 25 8-1-2014 Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Collard, Rosemary-Claire. "Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance." The Goose, vol. 13 , no. 1 , article 25, 2014, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol13/iss1/25. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Collard: Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Made, not born, machines this reduction is accomplished and what its implications are for animal life and Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction death. by DAWNE McCANCE After a short introduction in State U of New York P, 2013 $22.65 which McCance outlines the hierarchical Cartesian dualism (mind/body, Reviewed by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE human/animal) to which her book and COLLARD critical animal studies’ are opposed, McCance turns to what are, for CAS The field of critical animal scholars, familiar figures in a familiar studies (CAS) is thoroughly multi- place: Peter Singer and Tom Regan on disciplinary and, as Dawne McCance’s the factory farm. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in Society, Culture and the Media

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in society, culture and the media List of readings Approved by the board of the Department of Communication and Media 2019-12-03 Introduction to the critical study of human-animal relations Adams, Carol J. (2009). Post-Meateating. In T. Tyler and M. Rossini (Eds.), Animal Encounters Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 47-72. Emel, Jody & Wolch, Jennifer (1998). Witnessing the Animal Moment. In J. Wolch & J. Emel (Eds.), Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature- Culture Borderlands. London & New York: Verso pp. 1-24 LeGuin, Ursula K. (1988). ’She Unnames them’, In Ursula K. LeGuin Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences. New York, N.Y.: New American Library. pp. 1-3 Nocella II, Anthony J., Sorenson, John, Socha, Kim & Matsuoka, Atsuko (2014). The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of Intersectional Animal Liberation. In A.J. Nocella II, J. Sorenson, K. Socha & A. Matsuoka (Eds.), Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation. New York: Peter Lang. pp. xix-xxxvi Salt, Henry S. (1914). Logic of the Larder. In H.S. Salt, The Humanities of Diet. Manchester: Sociey. 3 pp. Sanbonmatsu, John (2011). Introduction. In J. Sanbonmatsu (Ed.), Critical Theory and Animal Liberation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1-12 + 20-26 Stanescu, Vasile & Twine, Richard (2012). ‘Post-Animal Studies: The Future(s) of Critical Animal Studies’, Journal of Critical Animal Studies 10(2), pp. 4-19. Taylor, Sunara. (2014). ‘Animal Crips’, Journal for Critical Animal Studies. 12(2), pp. 95-117. /127 pages Social constructions, positions, and representations of animals Arluke, Arnold & Sanders, Clinton R. -

Centre for the Study of Social and Political

CENTRE FOR THE STUDY ABOUT OF SOCIAL AND The Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements was established in 1992, and since then has helped the University of Kent gain wider POLITICAL recognition as a leading institution in the study of social and political movements in the UK. The Centre has attracted research council, European Union, and charitable foundation funding, and MOVEMENTS collaborated with international partners on major funding projects. Former staff members and external associates include Professors Mario Diani, Frank Furedi, Dieter Rucht, and Clare Saunders. Spri ng 202 1 Today, the Centre continues to attract graduate students and international visitors, and facilitate the development of collaborative research. Dear colleagues, Recent and ongoing research undertaken by members includes studies of Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, veganism and animal rights. Things have been a bit quiet in the center this year as we’ve been teaching online and unable to meet in person. That said, social The Centre takes a methodologically pluralistic movements have not been phased by the pandemic. In the US, Black and interdisciplinary approach, embracing any Lives Matter protests trudge on, fueled by the recent conviction of topic relevant to the study of social and political th movements. If you have any inquiries about George Floyd’s murder on April 20 and the police killing of 16 year old Centre events or activities, or are interested in Ma'Khia Bryant in Ohio that same day. Meanwhile, the killing of Kent applying for our PhD programme, please contact resident Sarah Everard (also by a police officer) spurred considerable Dr Alexander Hensby or Dr Corey Wrenn. -

2010 Schedule Chart (8 1/2 X 14 In

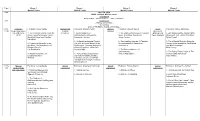

Time Room 1. Room 2. Room 3. Room 4. Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center 9:00 April 10, 2010 SUNY Cortland, Moffett Center Registration Sarat Colling - Elizabeth Green – Ashley Mosgrove 9:30 Introduction Anthony J. Nocella, II Welcoming Andrew Fitz-Gibbon and Mechthild Nagel 10:00 – Academic Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animals and Facilitator: Ronald Pleban Species Facilitator: Doreen Nieves Social Facilitator: Ashley Mosgrove 11:20 Repression Book Cultural Inclusion Movement Talk (AK Press, 1. The Carceral Society: From the Practices 1 Animal Subjects in 1. The Politics of Inclusion: A Feminist Strategy and 1. DIY Media and the Animal Rights 2010) Prison Tower to the Ivory Tower Anthropological Perspective Space to Critique Speciesism Tactic Analysis Movement: Talk - Action = Nothing Mechthild Nagel and Caroline Alessandro Arrigoni Jenny Grubbs Dylan Powell Kaltefleiter 2. An American Imperial Project: 2. Transcending Species: A Feminist 2. The Influential Activist: Using the 2. Regimes of Normalcy in the The Role of Animal Bodies in the Re-examination of Oppression Science of Persuasion to Open Minds Academy: The Experiences of Smithsonian-Theodore Roosevelt Jeni Haines and Win Campaigns Disabled Faculty African Expedition, 1909-1910. Nick Cooney Liat Ben-Moshe Laura Shields 3. The Reasonableness of Sentimentality 3. The Role of Direct Action in The 3. Adelphi Recovers „The 3. Conservation perspectives: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon Animal Rights Movement Lengthening View International wildlife priorities, Carol Glasser Ali Zaidi individual animals, and wildlife management strategies in Kenya Stella Capoccia 11:30- Species Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animal Facilitator: Anastasia Yarbrough Animal Facilitator: Brittani Mannix Animal Facilitator: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon 1:00 Relationships Exploitation Exploitation Exploitation and Domination 1. -

On Transfer of Sámi Traditional Knowledge: Scientification, Traditionalization, Secrecy, and Equality*

On Transfer of Sámi Traditional Knowledge: Scientification, Traditionalization, Secrecy, and Equality* Elina Helander-Renvall and Inkeri Markkula Introduction The aim of this chapter is to elaborate how Sámi traditional knowledge is ar- ticulated and transferred, especially as part of research activities. As a starting point, we will discuss traditional knowledge and its various understandings. Further on, we will trace and address some of the concerns that Sámi have in relation to how their reality is researched and described. Special attention will be paid to the secrecy surrounding some Sámi traditions and some knowl- edge in the context of conducting research on such issues; the scientifijication of Sámi knowledge; the traditionalization (actualization) of various traditions; and the need for equality between scientifijic and traditional knowledge. Traditional knowledge ( TK) has many defijinitions. Traditional knowledge may be defijined as knowledge that has a long historical and cultural continu- ity, having been passed down through generations, as Berkes has noted.1 In the book on traditional knowledge by Porsanger and Guttorm2 the concept árbediehtu (inherited knowledge, a Northern Sámi word) is used to refer to Sámi knowledge. They state that árbediehtu is ‘the collective wisdom and skills of the Sámi people used to enhance their livelihood for centuries. It has been * We would like to thank Regional Council of Lapland, European Regional Development Fund, and University of Lapland for the fijinancial support for the project Traditional Eco- logical Knowledge in the Sami Homeland Region of Finland which was conducted at the Arctic Centre, Rovaniemi during 1.1.2014-30.4.2015. The general aim of this project was to promote the status of Sami traditional ecological knowledge through support to the Sami craftswomen. -

Journal for Critical Animal Studies

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies Special issue Inquiries and Intersections: Queer Theory and Anti-Speciesist Praxis Guest Editor: Jennifer Grubbs 1 ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD GUEST EDITOR Jennifer Grubbs [email protected] ISSUE EDITOR Dr. Richard J White [email protected] EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE Dr. Matthew Cole [email protected] Vasile Stanescu [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas [email protected] Dr. Richard Twine [email protected] Dr. Richard J White [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Lindgren Johnson [email protected] Laura Shields [email protected] FILM REVIEW EDITORS Dr. Carol Glasser [email protected] Adam Weitzenfeld [email protected] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For more information about the JCAS Editorial Board, and a list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board, please visit the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 2 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD ............................................................................................................. 2 GUEST EDITORIAL .............................................................................................................. 4 ESSAYS From Beastly Perversions to the Zoological Closet: Animals, Nature, and Homosex Jovian Parry ............................................................................................................................. -

Philosophy 1

Philosophy 1 PHILOSOPHY VISITING FACULTY Doing philosophy means reasoning about questions that are of basic importance to the human experience—questions like, What is a good life? What is reality? Aileen Baek How are knowledge and understanding possible? What should we believe? BA, Yonsei University; MA, Yonsei University; PHD, Yonsei University What norms should govern our societies, our relationships, and our activities? Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy; Visiting Scholar in Philosophy Philosophers critically analyze ideas and practices that often are assumed without reflection. Wesleyan’s philosophy faculty draws on multiple traditions of Alessandra Buccella inquiry, offering a wide variety of perspectives and methods for addressing these BA, Universitagrave; degli Studi di Milano; MA, Universitagrave; degli Studi di questions. Milano; MA, Universidad de Barcelona; PHD, University of Pittsburgh Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy William Paris BA, Susquehanna University; MA, New York University; PHD, Pennsylvania State FACULTY University Stephen Angle Frank B. Weeks Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy BA, Yale University; PHD, University of Michigan Mansfield Freeman Professor of East Asian Studies; Professor of Philosophy; Director, Center for Global Studies; Professor, East Asian Studies EMERITI Lori Gruen Brian C. Fay BA, University of Colorado Boulder; PHD, University of Colorado Boulder BA, Loyola Marymount University; DPHIL, Oxford University; MA, Oxford William Griffin Professor of Philosophy; Professor -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

The Covid Pandemic, 'Pivotal' Moments, And

Animal Studies Journal Volume 10 Number 1 Article 10 2021 The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives Paula Arcari Edge Hill University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Arcari, Paula, The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives, Animal Studies Journal, 10(1), 2021, 186-239. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol10/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Covid Pandemic, ‘Pivotal’ Moments, and Persistent Anthropocentrism: Interrogating the (Il)legitimacy of Critical Animal Perspectives Abstract Situated alongside, and intertwined with, climate change and the relentless destruction of ‘wild’ nature, the global Covid-19 pandemic should have instigated serious reflection on our profligate use and careless treatment of other animals. Widespread references to ‘pivotal moments’ and the need for a reset in human relations with ‘nature’ appeared promising. However, important questions surrounding the pandemic’s origins and its wider context continue to be ignored and, as a result, this moment has proved anything but pivotal for animals. To explore this disconnect, this paper undertakes an analysis of dominant Covid discourses across key knowledge sites comprising mainstream media, major organizations, academia, and including prominent animal advocacy organizations. Drawing on the core tenets of Critical Animal Studies, the concept of critical animal perspectives is advanced as a way to assess these discourses and explore the illegitimacy of alternative ways of thinking about animals.