Law and Human Behavior Affective Forecasting About Hedonic Loss and Adaptation: Implications for Damage Awards Edie Greene, Kristin A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is It Possible to Accurately Forecast Suicide, Or Is Suicide a Consequence of Forecasting Errors?

UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM Is it Possible to Accurately Forecast Suicide, or is Suicide a Consequence of Forecasting Errors? Patterns of Action Dissertation Sophie Joy 5/12/2014 Word Count: 3938 Contents Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Can Individual Behaviour Be Forecasted? 4 Can Suicide be Accurately Forecasted? 5 The Suicide Process 6 Mental Health 8 Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide 8 A History of Suicidal Behaviours 8 Is Suicide a Consequence of Poor Affective Forecasting? 10 Can HuMans Accurately Forecast EMotions? 10 FocalisM 11 IMpact Bias 11 Duration Bias 11 IMMune Neglect 11 Application of Affective Forecasting Errors to Suicidal Individuals 12 What is the IMpact of Poor Affective Forecasting on Suicide? 13 Rational Choice Theory 13 Conclusion 15 Reference List 16 1 Is It Possible to Accurately Forecast Suicide, or is Suicide a Consequence of Forecasting Errors? “Where have we come from? What are we? Where are we going? ...They are not really separate questions but one big question taken in three bites. For only by understanding where we have come from can we make sense of what we are; only by understanding what we are can we make sense of where we are going” Humphrey, 1986, p. 174. Abstract Forecasting has been applied to Many disciplines however accurate forecasting of huMan behaviour has proven difficult with the forecasting of suicidal behaviour forMing no exception. This paper will discuss typical suicidal processes and risk factors which, it will be argued, have the potential to increase forecasting accuracy. Suicide is an eMotive social issue thus it is essential that the forecasting of this behaviour is atteMpted in order to be able to successfully apply prevention and intervention strategies. -

Why Feelings Stray: Sources of Affective Misforecasting in Consumer Behavior Vanessa M

Why Feelings Stray: Sources of Affective Misforecasting in Consumer Behavior Vanessa M. Patrick, University of Georgia Deborah J. MacInnis, University of Southern California ABSTRACT drivers of AMF has considerable import for consumer behavior, Affective misforecasting (AMF) is defined as the gap between particularly in the area of consumer satisfaction, brand loyalty and predicted and experienced affect. Based on prior research that positive word-of-mouth. examines AMF, the current study uses qualitative and quantitative Figure 1 depicts the process by which affective misforecasting data to examine the sources of AMF (i.e., why it occurs) in the occurs (for greater detail see MacInnis, Patrick and Park 2005). As consumption domain. The authors find evidence supporting some Figure 1 suggests, affective forecasts are based on a representation sources of AMF identified in the psychology literature, develop a of a future event and an assessment of the possible affective fuller understanding of others, and, find evidence for novel sources reactions to this event. AMF occurs when experienced affect of AMF not previously explored. Importantly, they find consider- deviates from the forecasted affect on one or more of the following able differences in the sources of AMF depending on whether dimensions: valence, intensity and duration. feelings are worse than or better than forecast. Since forecasts can be made regarding the valence of the feelings, the specific emotions expected to be experienced, the INTRODUCTION intensity of feelings or the duration of a projected affective re- Before purchase: “I can’t wait to use this all the time, it is sponse, consequently affective misforecasting can occur along any going to be so much fun, I’m going to go out with my buddies of these dimensions. -

Loneliness, Mental Health Symptoms and COVID-19 Okruszek, Ł.1, Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A.1,2*, Piejka, A.1*, Wiśniewska, M.1*, Żurek, K.1,2*

Safe but lonely? Loneliness, mental health symptoms and COVID-19 Okruszek, Ł.1, Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A.1,2*, Piejka, A.1*, Wiśniewska, M.1*, Żurek, K.1,2* 1. Social Neuroscience Lab, Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences 2. Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw * authors are listed alphabetically Corresponding author information: Łukasz Okruszek, Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Jaracza 1, 00-378 Warsaw, Poland (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract The COVID-19 pandemic has led governments worldwide to implement unprecedented response strategies. While crucial to limiting the spread of the virus, “social distancing” may lead to severe psychological consequences, especially in lonely individuals. We used cross- sectional (n=380) and longitudinal (n=74) designs to investigate the links between loneliness, mental health symptoms (MHS) and COVID-19 risk perception and affective response in young adults who implemented social distancing during the first two weeks of the state of epidemic threat in Poland. Loneliness was correlated with MHS and with affective response to COVID-19’s threat to health. However, increased worry about the social isolation and heightened risk perception for financial problems was observed in lonelier individuals. The cross-lagged influence of the initial affective response to COVID-19 on subsequent levels of loneliness was also found. Thus, the reciprocal connections between loneliness and COVID- 19 response may be of crucial importance for MHS during COVID-19 crisis. Keywords: loneliness, mental well-being, mental health, COVID-19, preventive strategies Data availability statement: Data from the current study can be accessed via https://osf.io/ec3mb/ Introduction Within three months-time since the first case of the novel coronavirus originating from Wuhan (Hubei, China) has been officially reported, COVID-19 has spread to 210 countries and territories affecting over 1602 thousand individuals and causing 95735 deaths as of 10th April (Dong, Du, & Gardner, 2020). -

Examining Affective Forecasting and Its Practical and Ethical Implications

Examining Affective Forecasting and its Practical and Ethical Implications Emily Susan Brindley BSc Psychology 2009 Supervisor: Prof. David Clarke Contents Page Introduction 1 1. Affective Forecasting – What do we know? 1 2. Biases – Why people cannot predict their emotions accurately 3 2.1 Impact Bias 3 2.2 ‘Focalism’ 4 2.3 Immune Neglect 4 2.4 Dissimilar Context 4 3. The Self-Regulating Emotional System 5 4. Affective Forecasting Applied 6 4.1 Healthcare 6 4.2 Law 7 5. Can AFing be improved? 8 6. Ethics: Should people be taught to forecast more accurately? 10 Conclusions 12 References 13 Examining Affective Forecasting and its Practical and Ethical Implications Introduction Emotions are important in guiding thoughts and behaviour to the extent that they are used as heuristics (Slovic, Finucane, Peters & MacGregor, 2007), and are crucial in decision-making (Anderson, 2003). Affective forecasting (AFing) concerns an individual’s judgemental prediction of their or another’s future emotional reactions to events. It is suggested that “affective forecasts are among the guiding stars by which people chart their life courses and steer themselves into the future” (Gilbert, Pinel, Wilson, Blumberg & Wheatley, 1998; p.617), as our expected reactions to emotional events can assist in avoiding or approaching certain possibilities. We can say with certainty that we will prefer good experiences over bad (ibid); however AFing research demonstrates that humans are poor predictors of their emotional states, regularly overestimating their reactions. Further investigation of these findings shows that they may have critical implications outside of psychology. If emotions are so influential on behaviour, why are people poor at AFing? Furthermore, can and should individuals be assisted in forecasting their emotions? These issues, along with the function of AFing in practical applications, are to be considered and evaluated. -

Matt Hayes of School of Accountancy W.P

Distinguished Lecture Series School of Accountancy W. P. Carey School of Business Arizona State University Matt Hayes of School of Accountancy W.P. Carey School of Business Arizona State University will discuss “Risky Decision, Affect, and Cognitive Load: Does Multi-Tasking Reduce Affective Biases?” on September 13, 2013 1:00pm in MCRD164 Risky Decisions, Affect, and Cognitive Load: Does Multi-Tasking Reduce Affective Biases? Matt Hayes W.P. Carey School of Accountancy First Year Research Paper August 30, 2013 Abstract This paper examines the effects of cognitive load on risky choices in a capital budgeting setting. Research by Moreno et al. (2002) demonstrated that affective reactions to a choice can alter risk-taking tendencies. Their control participants’ decisions were influenced by the framing effects of prospect theory. However, once affective cues were introduced, participants’ reactions to these cues dominated the framing effect, leading to prospect theory inconsistent choices. Some studies of cognitive load show that high cognitive load leads to greater reliance on affective cues (Shiv and Fedorikhin 1999). Other research has shown high cognitive load may impair processing of affective information (Hoerger et al. 2010; Sevdalis and Harvey 2009). In this paper I am able to replicate the original finding in Moreno et al. (2002), but find that cognitive load moderates the affect-risk-taking relationship. Specifically, in a gain setting, cognitive load versus no load participants were more likely to make prospect theory consistent choices, despite the presence of affective cues. These findings suggest that cognitive load may inhibit processing of affective information, and is an important consideration when studying decision making in managerial accounting. -

Towards a Conceptual Model of Affective Predictions in Palliative Care

Accepted Manuscript Towards a conceptual model of affective predictions in palliative care Erin M. Ellis, PhD, MPH, Amber E. Barnato, MD, MPH, Gretchen B. Chapman, PhD, J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, PhD, Jennifer S. Lerner, PhD, Ellen Peters, PhD, Wendy L. Nelson, PhD, MPH, Lynne Padgett, PhD, Jerry Suls, PhD, Rebecca A. Ferrer, PhD PII: S0885-3924(19)30059-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.02.008 Reference: JPS 10037 To appear in: Journal of Pain and Symptom Management Received Date: 4 September 2018 Revised Date: 24 January 2019 Accepted Date: 10 February 2019 Please cite this article as: Ellis EM, Barnato AE, Chapman GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Lerner JS, Peters E, Nelson WL, Padgett L, Suls J, Ferrer RA (2019). Towards a conceptual model of affective predictions in palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 57(6), 1151-1165. doi: https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.02.008. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 1 Running title: AFFECTIVE PREDICTIONS IN PALLIATIVE CARE Towards a conceptual model of affective predictions in palliative care Erin M. Ellis, PhD, MPH (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA; [email protected]) Amber E. -

Immune Neglect: a Source of Durability Bias in Affective Forecasting

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 1998 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1998, Vol. 75, No. 3, 617-638 0022-3514/98/$3.00 Immune Neglect: A Source of Durability Bias in Affective Forecasting Daniel T. Gilbert Elizabeth C. Pinel Harvard University University of Texas at Austin Timothy D. Wilson Stephen J. Blumberg University of Virginia University of Texas at Austin Thalia P. Wheatley University of Virginia People are generally unaware of the operation of the system of cognitive mechanisms that ameliorate their experience of negative affect (the psychological immune system), and thus they tend to overesti- mate the duration of their affective reactions to negative events. This tendency was demonstrated in 6 studies in which participants overestimated the duration of their affective reactions to the dissolution of a romantic relationship, the failure to achieve tenure, an electoral defeat, negative personality feedback, an account of a child's death, and rejection by a prospective employer. Participants failed to distinguish between situations in which their psychological immune systems would and would not be likely to operate and mistakenly predicted overly and equally enduring affective reactions in both instances. The present experiments suggest that people neglect the psychological immune system when making affective forecasts. I am the happiest man alive. I have that in me that can convert would be hard pressed to name three, and thus most people poverty into riches, adversity into prosperity, and I am more invul- would probably expect this news to create a sharp and lasting nerable than Achilles; fortune hath not one place to hit me. -

The Impact of Emotion on Perception, Attention, Memory, and Decision-Making

Review article: Medical intelligence | Published 14 May 2013, doi:10.4414/smw.2013.13786 Cite this as: Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13786 The impact of emotion on perception, attention, memory, and decision-making Tobias Broscha,b, Klaus R. Schererb, Didier Grandjeana,b, David Sandera,b a Department of Psychology, University of Geneva, Switzerland b Swiss Centre for Affective Sciences, University of Geneva, Switzerland Summary ing the importance of emotional processes for a success- ful functioning of the human mind. For example, neuro- Reason and emotion have long been considered opposing psychological studies have shown that patients with emo- forces. However, recent psychological and neuroscientific tional dysfunctions due to brain lesions can be highly im- research has revealed that emotion and cognition are paired in everyday decision-making and social interactions. closely intertwined. Cognitive processing is needed to elicit Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated how brain re- emotional responses. At the same time, emotional re- gions previously thought to be purely “emotional” (e.g., sponses modulate and guide cognition to enable adaptive amygdala) or “cognitive” (e.g., frontal cortex) closely in- responses to the environment. Emotion determines how we teract to make complex behaviour possible. Psychology ex- perceive our world, organise our memory, and make im- periments have illustrated how emotion can change our portant decisions. In this review, we provide an overview perception, attention, and memory by focusing them on im- of current theorising and research in the Affective Sciences. portant aspects of the environment. This research has re- We describe how psychological theories of emotion con- vealed to what extent emotion and cognition are related, or ceptualise the interactions of cognitive and emotional pro- even inseparable. -

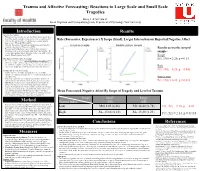

Trauma and Affective Forecasting: Reactions to Large Scale and Small Scale Tragedies

Trauma and Affective Forecasting: Reactions to Large Scale and Small Scale Tragedies Rizeq, J. & McCann, D. Social Cognition and Psychopathology Lab, Department of Psychology, York University IntroductionIntroduction Resultsesults Affective Forecasting • Will you feel more negative towards 5 or 5000 reported dead in forest fires? Most people’s actual reactions are not what we would predict! Role (Forecaster, Experiencer) X Scope (Small, Large) Interaction on Reported Negative Affect • Affective forecasting involves predicting one’s emotion towards future events (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). • Affective forecasts are inaccurate as compared to actual emotional Canadian Sample Middle Eastern Sample reports by experiencers (Wilson et al., 2000). • Previous work found that forecasters calibrate their emotional Results across the merged predictions to the scope of a tragedy, while those who experience the sample: events report emotions that are insensitive to the scope of the reported tragedy (Dunn & Ashton-James, 2007). Scope Two Systems of Information Processing F(1, 190) = 2.20, p = 0.14 • Forecasters tend to rely on a rational thought processing system that is deliberate, analytic, slow and logical. Experiencers, on the other hand, are overwhelmed by the emotional experience and tend to rely on an experiential thought processing system that is rapid and automatic. Role Trauma and Affective Forecasting F(1, 190) = 4.20, p = 0.042 • Trauma experience is highly emotional and leaves its victims sensitized to emotional situations and cues, relying on automatic and rapid processing. Interaction • This study explored the role of past personal trauma experience in emotional predictions toward small-scale and large-scale tragedies. F(1, 190) = 6.23, p = 0.013 • Hypothesis: In contrast to the typical pattern of results found for affective forecasters, it was expected that participants with high trauma effect would predict similar emotions to small-scale and large- scale tragedies, relying on the experiential processing system. -

Predicting Future Emotions from Different Points of View: the Influence of Imagery Perspective on Affective Forecasting Accuracy

Predicting Future Emotions from Different Points of View: The Influence of Imagery Perspective on Affective Forecasting Accuracy THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Karen A. Hines Graduate Program in Psychology The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Lisa Libby, Advisor Ken Fujita Wil Cunningham Copyright by Karen Hines 2010 Abstract Humans have the ability to imagine future points in time, and one way they use this ability is to make predictions about how they will feel in response to potential future outcomes. The current research examined whether the accuracy of these affective forecasts differed as a result of the visual perspective (own first-person versus observer’s third-person) that individuals took to imagine future events. When people use a first- person perspective, they make meaning of events in terms of their gut reactions to the events. In contrast, when they use a third-person perspective, they incorporate their broader knowledge and self-theories into their interpretations of the event. There is evidence that most individuals are unable to interpret online experiences without evaluating the events in terms of their self-theories. Therefore, their interpretations of events are more similar to online experiences when they picture events from a third- person perspective as opposed to a first-person perspective. We propose that individuals make more accurate forecasts when they use a third-person perspective instead of a first- person perspective because when using a third-person perspective they make meaning of imagined events in a similar manner to that which they use to make meaning of online experiences. -

The Somatic Marker Theory in the Context of Addiction: Contributions to Understanding Development and Maintenance

Psychology Research and Behavior Management Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW The somatic marker theory in the context of addiction: contributions to understanding development and maintenance Vegard V Olsen1 Abstract: Recent theoretical accounts of addiction have acknowledged that addiction to Ricardo G Lugo1 substances and behaviors share inherent similarities (eg, insensitivity to future consequences and Stefan Sütterlin1,2 self-regulatory deficits). This recognition is corroborated by inquiries into the neurobiological correlates of addiction, which has indicated that different manifestations of addictive pathology 1Section of Psychology, Lillehammer University College, Lillehammer, share common neural mechanisms. This review of the literature will explore the feasibility of 2Department of Psychosomatic the somatic marker hypothesis as a unifying explanatory framework of the decision-making Medicine, Division of Surgery deficits that are believed to be involved in addiction development and maintenance. The somatic and Clinical Neuroscience, Oslo University Hospital – Rikshospitalet, marker hypothesis provides a neuroanatomical and cognitive framework of decision making, Oslo, Norway which posits that decisional processes are biased toward long-term prospects by emotional marker signals engendered by a neuronal architecture comprising both cortical and subcortical circuits. Addicts display markedly impulsive and compulsive behavioral patterns that might be understood as manifestations of decision-making processes that fail to take into account the long-term consequences of actions. Evidence demonstrates that substance dependence, pathological gambling, and Internet addiction are characterized by structural and functional abnormalities in neural regions, as outlined by the somatic marker hypothesis. Furthermore, both substance dependents and behavioral addicts show similar impairments on a measure of decision making that is sensitive to somatic marker functioning. -

Affective Forecasting and Well Being

Swarthmore College Works Psychology Faculty Works Psychology 2013 Affective Forecasting And Well Being Barry Schwartz Swarthmore College, [email protected] R. Sommers Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-psychology Part of the Psychology Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Barry Schwartz and R. Sommers. (2013). "Affective Forecasting And Well Being". Oxford Handbook Of Cognitive Psychology. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376746.013.0044 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-psychology/527 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Affective Forecasting and Well-Being Affective Forecasting and Well-Being Barry Schwartz and Roseanna Sommers The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Psychology Edited by Daniel Reisberg Print Publication Date: Mar 2013 Subject: Psychology, Cognitive Psychology Online Publication Date: Jun 2013 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376746.013.0044 Abstract and Keywords Every decision requires a prediction, both about what will happen and about how the de cider will about what happens. Thus, decisions require what is known as . This chapter reviews evidence that people systematically mispredict the way experiences will feel. First, predictions about the future are often based on memories of the past, but memories of the past are often inaccurate. Second, people predict that the affective quality of expe riences will last, thereby neglecting the widespread phenomenon of adaptation. Third, in anticipating an experience, people focus on aspects of their lives that will be changed by the experience and ignore aspects of their lives that will be unaffected.