Cageographer1998.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nevada Traverse Journal of the Professional Land Surveyors of Nevada

THE NEVADA TRAVERSE Journal of the Professional Land Surveyors of Nevada Institutional Affiliate National Society of Professional Surveyors • Member Western Federation of Professional Surveyors Vol. 45, No.4 • December 2018 2018 ‘GPS On Benchmarks’ Campaign...Page 8 Brothers, Part II.....Page 5 Who’s Who in NALS 2018 State Association Officers Great Basin Chapter Officers Jerry Juarez, President Christopher S. Konakis PLS, President and Chapter Representative Manhard Consulting Email:[email protected] [email protected] Norman Rockwell, PE, PLS, President-Elect Jason Higgins, President-Elect WMK Surveying, Inc Jolene Hoffman, Secretary (acting) [email protected] Email: [email protected] William Nisbet, PLS, Treasurer Greg Phillips, Secretary Lumos & Associates [email protected] Lahontan Chapter Officers Jason Fackrell, Treasurer Doug Larson, President Poggemeyer Design Group, Inc. NV Energy [email protected] [email protected] Todd Enke, President-Elect The Nevada Traverse Todd A. Enke R.O. Anderson [email protected] Carl C.de Baca, PLS, Editor, The Nevada Traverse P.O. Box 1586 Ken Mandryk, Secretary Elko, NV 89803 Wood Rodgers Email: [email protected] [email protected] John Gomez, Treasurer Executive Office Wood Rodgers [email protected] NALS Executive Office 526 South E Street Justin Moore, Chapter Representative Santa Rosa, CA 95404 Odyssey Email: [email protected] [email protected] NSPS Director for Nevada Southern Nevada Chapter Officers Carl C.de Baca, PLS Lumos and Associates, Inc Jeff Miller, President 9222 Prototype Drive DataSight USA Reno, NV 89521 [email protected] [email protected] Gene Sawyer, President-Elect Clark County Survey Department Directors [email protected] Gene Sawyer, Director – Southern Nevada Nicholas Ariotti, Secretary Clark County Survey Department E.G. -

Public Land Acquisition for Environmental Protection: Structuring a Program for the Lake Tahoe Basin

Public Land Acquisition for Environmental Protection: Structuring a Program for the Lake Tahoe Basin Richard J. Fink* CONTENTS Introduction ................................................... 486 I. The Context of Land Acquisition at Lake Tahoe ........... 493 A. The Lake and Its Basin ............................. 493 B. Land Ownership and Use in the Basin ................ 494 C. Urbanization of the Tahoe Basin and Its Consequences ........................................ 500 D. Planning and Regulation at Lake Tahoe .............. 504 1. Sewage Export .................................... 504 2. The 1969 Interstate Compact ...................... 505 3. The 1980 Interstate Compact ...................... 507 E. Summary: Impact of the Context of Lake Tahoe on Public Land Acquisition Programs .................... 511 II. The Modem Role of Public Land Acquisition at Lake T ahoe .................................................... 512 A. Genesis of the Current Acquisition Programs ......... 513 1. Proposals for Expanding Public Land Acquisition.. 513 2. Forest Service Acquisitions Under the Land and Water Conservation Fund ......................... 518 3. State Park Acquisitions at Lake Tahoe and At- tempts at Interstate Cooperation .................. 520 4. Summary: Lessons from Tahoe Basin Acquisitions Before 1980 ...................................... 522 Copyright © 1991 by ECOLOGY LAW QUARTERLY * Associate Professor, California Western School of Law, San Diego; J.D. 1974, Stan- ford Law School; A.B. 1970, Stanford University. The author -

Map of the United Mexican States, As Organized and Defined by Various Acts of the Congress of Said Republic, and Constructed According to the Best Authorities

� 0 Figure 1. Portion of the "Map of the United Mexican States, as organized and defined by various acts of the Congress of said republic, and constructed according to the best authorities. Revised edition. Published at new York, in 1847, by J. Disturnell." This section shows almost the entire region known as Alta California and is referred to in both the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and in J. Ross Browne's Report of the Convention of the California Constitution in September and October 1849. [Edward M. Douglas, Boundaries. Areas. Geographic Centers and Altitudes of the United States and the Several States, USGS Bulletin 817, Plate 6 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office), 1930.) California's Northeast Border: Politi£al PragntatisJD Turned Territorial I10perative Gregory A. Reed School? Keywords: Definition, Delimitation, Demarcation, Administration, Territorial Impera tive, and Stamping Ground Abstrad: The placement of California's Northeast border is usuaiiy ascribed to issues of slavery, greed and compromise. In reality, the arbitrary definition and delimitation of this boundary stemmed from problems of physical size, acculturation, and the perceived, relative value of the physical landscape. The resultant impacts on the cultural landscape still reverberate today. Introdudion As a territorial species, we humans have "an inherent drive to gain and defend an exclusive property' (Ardrey 1966, 3) Today, political geogra phers relate the concept of exclusive property with the sovereign state. As Pliny noted in 77 A.D.: "Great folly it is then, a meere madnesse, that some have devised and thought in their minde to measure it [the World]; yea, and durst in writing to set down the dimensions thereof.. -

Proquest Dissertations

A DISSERTATION ON CANADIAN BOUNDARIES TBEIR EVOLUTION, ESTABLISHMENT AND SIGNIFICANCE By Norman L. Nicholson Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Ottawa. Ottawa, Canada, 1951 UMI Number: DC53316 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform DC53316 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was prepared under the direction of the Vice- Dean of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa, Dr. R. H. Shevenell, o.m.i., and the Professor of Geography of the same Faculty, T. Jost. Active assistance in the organization, method and content of the study was also given by Dr. B. Zaborski, Professor of Geography at McGill University and, in addition, the Director of the Geographical Branch of the Federal Department of Mines and Technical Surveys, Dr. J. W. Watson, gave generously of his time to discuss special problems and facilitate the acquisition of source material. -

The Times.) for the Martlet in the Near Future

COAL. COAL. 1 ♦ HAIiL * WALKER FURNITURÈ „ A Wellington Colliery We bave first-class and up-to- 4 datf- Furniture and Plano Moving Co. PADDED VAN. Phone 11M GOVKRNMKNT ST. I* Burt’s Wood Yard Phone IN. II PAN DOHA ATI VOL. 47. VICTORIA, B. C„ TUESDAY, MARCH 16, 1909. No. 63 VAR! UNLESS ELECTROCUTED. KFXJLVdK'M ltETICENCE. NEW SCALE OF St. Johns, Que.. March 16.— John For on! if that Windsor, Ont., March 16.—Because he ant. 3.1 years, employed by the St. objected to acknowledge his Identity SERVIA YIELDS Johns Electriç Lbfnt1 Company, was CAUCUS COULD end declined to state whether- he pos- electrocuted while working on the roof o«i.y set ne ressed sufficient funds to make * him WATER RATES of the electric light station hen^ He NOW' eligible to enter Canada, Francis Pet- grasped a live wire with his bare TENSION IN BALKANS tingill, member of a religious brother hand while his rubber* gloves were un hood. «pent several hour* on the De TWENTY PER CENT. JUMP ’ der his coat. troit river. Pettlngiil. who 1* a mem OF GRAVE CHARACTER ber of the Christian Brethren, was»on CAVK-IN KILLS FIVE his way from Cincinnati to Chatham to FOR ALL RESIDENCES enter ;i retreat n< fljially capitulated Quebec; March 16.—A cave-In on *the | and showed that he possessed several / ------------ Austria Demands a Clear Ex hundred dollars. Transcontinental railway, twenty A Comparison Between the Ex planation—Turkey’s Part miles from La Tuque, resulted In the death Of live laborers. Further details SEIZURE OF PAINTINGS. -

Broadcast Engineering the Technical Journal of the Broadcast -Communications Industry

A HOWARD W. SAMS PUBLICATION DECEMBER 1962 75c FEATURING Mobile Videotape Installation-TWW, England 10 Preventive Maintenance for the Studio 12 Installing Directional Antenna Systems 14 Camera Tube Alignment Using 30 Cycles 26 1962 Subjject Reference Index 32 Broadcast Engineering the technical journal of the broadcast -communications industry www.americanradiohistory.com COMPACT QUAL TI PAC KAGE FOR ITA'S MEDIUM POWER FM TRANSMITTERS Designed for stereo and multiplex operation, ITA FM trans- High Performance Features 5, 7.5 and 10 kw power levels are the most compact, mitters in Silicon Rectifiers fully accessible transmitters sold. Their single cabinet con- Self Neutralized struction requires less than 6 square feet of floor space and Provisions vertical arrangement of components virtually eliminates blind Remote Control spots. Automatic recycling assures continuity of operation and Expansible to higher power extra long -life ceramic tetrode PA tubes greatly reduce Free test and tune-up operating costs ! They're your best buy in medium power FM transmitters. ITA ELECTRONICS CORPORATION BROADCAST DIVISION LANSDOWNE, PENNSYLVANIA 2.1999 Chicago, III. AN 3-3797 Jacksonville, Fla. EL 6-0121 New York City, N.Y. CH Portland, Ore. CA 2.2651 rrA Cincinnati, Ohio. CH 1-6386 Kansas City, Mo. GR 1-2838 Dallas, Texas. FL 7.9607 Lansdowne, Pa. CL 9-8200 Washington, D.C. 337.2884 Los Angeles, Cal. MA 2.8552 www.americanradiohistory.com "Sylvania GB -5749 cuts costs 50%!" Paul F. Rex, Chief Engineer, WISR, Butler, Penna., "Naw we enjoy excellent fidelity-no thumps - says - "Sylvania Gold Brand 5749 has solved with 15 to 17db of compression. -

Local Operations Follow Failure of Enemy's Offensive

WEATHER FORECASTS ♦ ♦ WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT For 34 hours ending 6 p.m Thursday: Pantagee—Vaudeville Victoria and rioinlty—Northerly winds, Princess—King of the Cannibal Islands. fine and warm to-day and on Thursday. Variety—Jack Plckford. Lower Mainland—Continued ftn6 and Romano—Mrs Vernon Cggtle. warm to-day and on Thursday. Columbia—Bessie Barrlscale. Pomlnioilow—My- rFour ---------------- Years lb Germany. VOL. 52. NO. 137 VICTORIA, B. C., WEDNESDAY, JUNE 5, 1918 SIXTEEN PAGES LOCAL OPERATIONS FOLLOW FAILURE OF ENEMY’S OFFENSIVE Germans Seize Still No Munitions Aboard- U BOAT RAD HAS NO Another Norwegian Ships British Use ALLIED TROOPS ON AISNE-MARNE EFFECT ON SENDING Ship Promised Safety to Carry Wounded SALIENT BREAK UP LOCAL ENEMY Washington. June 6.—The Norwe London. June S.—The British Admir gian steamship Eikundaaund. which alty in a statement denies a German had a German sale conduct, hak been wireless report that a captured English captured by a German submarine and medical student had seen munitions OF AMERICAN TROOPS taken to Swinemunde as a prise, ad unloaded from the hospital ship West ATTEMPTS AND INFLICT LOSSES vice» to the State Department said to day. The ship was on her way to ern Australia in Rouen Harbor. "No munitions of any description Stockholm with a cargo of herring con- ever was carried by the Western Aus Daniels Says Navy Will Keep Way Open for Un si gned to the Swedish Food Commis tralia or any other British hospital German Thrust on Extended Front Has Fallen Short sion. ship." says the statement. checked Movement of Men and Munitions to France; and Contest Is Taking Form of a War of Position; American Schooner Mengel Was Sunk Sunday GERMANS FORCED TO STOP TO VICTORIA NOW British Make Raids and Repulse a German Raid Washington- June 5.—Whatever the -purpose of the German sub Has Reached Fort Yukon anc London, June 6.—German masses no longer hurl themselves at marine raid off the Atlantic coast of the United States, and whatever DRIVE WITHOUT ATTAINING the Allied line in France along extended fronts. -

Order in Council 955/1923

955. ✓ , AD. 19 x Approved and ordered this day of lieu tena0-675Cernor. At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. MacLean in the Chair. Mr. Pattullo Mr. Manson mr.Suth,r1and Mr. Mr. mr. Mr. To His Honour Ai-- (pa.. The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: . The undersigned has the honour to recommend I - p.a 4,as 4-o/4-y 1 u 1/3 q THAT, pursuant to Seotion 3 of the "grazing Act," Chapter 30 of the Statutes of 1919, the areas comprised in the existing eight forest districts of the Province, as described in Order-in-Council No. 880, approved on the 21st day of July, 1923, be respectively constituted grazing districts for the purposes of said Aot, and that a Proclamation be issued and published in the Gazette a000rdingly. ,A / DATED THIS Ai OP N A. D. 1923. Miplmtkrof lands. APPROVED THIS r ".1 / DAY OP c A. D. 1923. 7.5 Presiding member o?aiTiiioutive Connoil. (li4 '11 Y ".' /9 3. ', I.. t , r• • • C 9. 3 o c. THE BRITISH COLUMBIA GAZETTE. DEPARTMENT OF LANDS. the 'south-we'd corner of Lot 7517; thence easterly following the !southerly boundaries of said Lot 7517 and of Lot 3214 to the south-Pant corner of said FOREST DISTRICI'S• Lot ;1214; thence southerly following the westerly boundary of Lot 3100 to the nouth-west corner OTICE is hereby given that, under authority thereof; thence easterly following the southerly N etntalned In geetion 5 of chapter 17 of the bound:01ot of .aid Lot 3150 and of lots 3151. -

Ecotopian Fiction As a Continuation of Utopian Literature and Soft Science Fiction

Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Dimitri Neyt West Coast Ecotopias Green Futures at the Intersection of Speculative Fiction, Environmental Literature, and Bioregionalism Paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” May 2013 Supervisor Dr. Sarah Posman Department of Literature 2 West Coast Ecotopias Green Futures at the Intersection of Speculative Fiction, Environmental Literature, and Bioregionalism DIMITRI NEYT Dimitri Neyt 3 4 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the advice and guidance of my supervisor, Dr. Sarah Posman. I would also like to thank Dr. Yuri Cowan, who supervised my B.A. thesis and who suggested the subject of environmental science fiction to me. I should thank the staff at the faculty library, as well as Wilfried Swartelé of the philosophy seminar library, for helping me find useful resources. I am very grateful for the support friends and family have offered me. Specifically, I would like to thank my parents, for introducing me to America’s natural beauty and for supporting my studies, and my girlfriend Jolien, who has followed this project with great dedication. I am most thankful for the constant encouragement she has offered me and for the wonderful proofreading she has done, despite her own busy schedule. No one has been as influential as my good friend and moral compass Joeri Van der Sype, who has constantly challenged my own preconceptions and who has given me valuable insights into the intersection of environment, politics, and economy. The acknowledgements being what they are – a personal note of gratitude and an acknowledgement of one’s influences – I must mention John Muir, who inspired a deeper, almost spiritual love for nature in me, and John Burroughs, who made me realize nature is always right around the corner. -

French Troops Take Bite at Tip of Amiens Salient

WEATHER FORECASTS WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT For SI hours endlns 6 p. m. Thursday : Victoria and vicinity—Mostly cloudy v Royal Victoria—Cyril Maude. and oooi, with rain P&ntages—Vaudeville. %mtz Variety—“Birth." -c Lower Mainland—Mostly cloudy and Dominion—Madame Petrova. coot with |aln. Romano—"Morgan's Raiders.*' Columbia—“For Freedom of World.** VOL. 52. NO. 119 VICTORIA, B. C., WEDNESDAY, MAY 15, 1918 EIGHTEEN PAGES FRENCH TROOPS TAKE BITE AT TIP OF AMIENS SALIENT British Airmen Drop SUBURB OF PRAGUE DECLARED IN " Nearly Five Bombs CAPTURE OF WOOD TO SOUTHEAST to One by Germans London, May 16.—In the month of A STATE OF SIEGE AS FERMENT April British airmen dropped 6,033 bombs behind the enemy lines along OF AMIENS BY FRENCH IMPROVES the British front in Francs and Bel- lium.. In the same period the enemy 1:ropped 1,344. in the terrain - occupied SPREADS THROUGH ALL BOHEMIA by the British troops. ALLIES’ POSITION IN THAT AREA Austro-Hungarian Government Faced With Steadily HIS SHIPBUILDING Germans Counter-Attack Strongly in Effort to Retake Increasing Spirit of Revolt; 150 Women Arrested FIREMAN KILLED AND ONE FIRM SUFFERS FIRE as Result of Demonstrations LOSS; J. J. COUGHLAN Ground From French But Attempt Is Failure; Raid SHIP RUINED BY FIRE IN Repulsed by Canadian Troops London, May 15.—A state of siege has been declared at Smichow, a suburb of Prague, Bohemia, and the troops there hare been sent _ COUGHLAN YARD, VANCOUVER London, May 15.—The expected renewal of the German offensive away, an Exchange Telegraph dispatch from Amsterdam reports. -

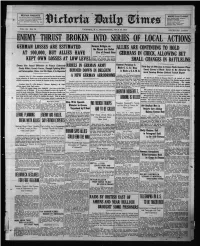

Enemy Thrust Into Series of Local Actions

♦ WEATHER FORECASTS ♦ WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT PV*r 36 hour* ending S p. m. Thursday: Royal Victoria—Mary Flckfordb Victoria and vicinity—Light to moder Vantages—Vaudeville. ate winds, continued flue and hot. Dominion—"A Modern Lorelei.” • Lower Mainland—Continued fine and Variety—Wallace Reid. Romano— Mrs. Vernon Castle. Columbia—Mary Anderson. VOL. 53. NO. 14 VICTORIA, B. C., WEDNESDAY, JULY 17, 1918 FOURTEEN PAGES ENEMY THRUST INTO SERIES OF LOCAL ACTIONS German Bridges on GERMAN LOSSES ARE ESTIMATED the Marne Are Under ALLIES ARE CONTINUING TO HOLD AT 100,000, ROT ALLIES HAVE Fire of French Guns GERMANS IN CHECK, ALLOWING BUT London, July 17.-—French counter attacks have breught the German bridges over the Marne under the fire KEPT OWN LOSSES AT LOW LEVEL ef French artillery of medium calibre. SMALL CHANGES IN BATTLELINE Enemy Has Found Offensive in France Extremely General Pershing Is REBELS IN GERMAN ARMY Third Day of Offensive in France Finds German Plans Costly Affair; French Forces, Though Fighting With Made G. C. B.; Bliss 44 Upset; Enemy's Efforts Seem to Be Directed To out Interruption, Have Lost No Guns, It Is Reported Is Made a G.C. M. G. BURNED DOWN IN ward Turning Rheims Salient; French Report London, July 17.—General Pershing, London, July 17.—The casualties suffered by the German army A NEW GERMAN AERODROME Commander-in-Chief ef the American in the offensive in France up to the present are estimated to numbel1 Army in France, has been awarded the Ob the French Front in France, Jnly 17.—A period of forty, Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath, 100,000, according to news received in London to-day from the front, and General Tasker H. -

Economic Aspects of Bycatch Reduction

Workshop Report: Economic Aspects of Bycatch Reduction Andrew Kitts, Lee Benaka, Dennis Heinemann, Sabrina Lovell, Noelle Olsen, and Dale Squires (editors) U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-214 February 2021 Workshop Report: Economic Aspects of Bycatch Reduction A. Kitts, L. Benaka, D. Heinemann, S. Lovell, N. Olsen, and D. Squires (editors) NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-214 February 2021 U.S. Department of Commerce Wynn Coggins, Acting Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Benjamin Friedman, Acting NOAA Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service Paul Doremus, Acting Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Recommended citation: A. Kitts, L. Benaka, D. Heinemann, S. Lovell, N. Olsen, and D. Squires (editors). 2021. Workshop Report: Economic Aspects of Bycatch Reduction. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS- F/SPO-214, 46 p. Copies of this report may be obtained online at: http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/tech-memos/ ii Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ iv Introduction and Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 Opening Remarks.......................................................................................................................................... 2 Mitigating Fisheries Bycatch: Regulatory