Borrowed Light Barbara Ernst Prey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before Your Visit Lay a Foundation So That the Youngs

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before your visit Lay a foundation so that the youngsters know why they are going on this trip. Talk about things for the students to look for and questions that you hope to answer at the Village. Remember that the outdoor experiences at the Village can be as memorable an indoor ones. Information to help you is included in this package, and more is available online at www.hancockshakervillage.org. Plan to divide into small groups, and decide if specific focus topics will be assigned. Perhaps a treasure hunt for things related to a focus topic can make the experience more meaningful. Please review general museum etiquette with your class BEFORE your visit and ON the bus: • Please organize your class into small groups of 510 students per adult chaperone. • Students must stay with their chaperones at all times, and chaperones must stay with their assigned groups. • Please walk when inside buildings and use “inside voices.” • Listen respectfully when an interpreter is speaking. • Be respectful and courteous to other visitors. • Food or beverages are not allowed in the historic buildings. • No flash photography is allowed inside the historic buildings. • Be ready to take advantage of a variety of handson and mindson experiences! Arrival Procedure A staff member will greet your group at the designated Drop Off and Pick Up area – clearly marked by signs on our entry driveway and located adjacent to the parking lot and the Visitor Center. We will escort your group to the Picnic Area, which has rest rooms and both indoor and outdoor picnic tables. -

Guide I Bound Manuscripts

VOLUME I GUIDE TO BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTION OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 2001 Compiled and annotated by Dr. Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright © 2001 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. CONTENTS PREPARER’S NOTE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ORIGINAL BOUND MANUSCRIPTS ALFRED 2 ENFIELD, CT 2 GROVELAND, NY 3 HANCOCK, MA 3 HARVARD, MA 6 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 8 TYRINGHAM, MA 20 UNION VILLAGE, OH 21 UNKNOWN COMMUNITIES 21 COPIED BOUND MANUSCRIPTS CANTERBURY, NH 23 ENFIELD, CT 24 HANCOCK, MA 24 HARVARD, MA 26 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 27 NORTH UNION, OH 30 PLEASANT HILL, KY 31 SOUTH UNION, KY 32 WATERVLIET, NY 33 UNKNOWN COMMUNITY 34 MISCELLANEOUS 35 PREPARER'S NOTE: THE BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS A set of most remarkable documents, handwritten by the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly called the Shakers, was produced by their leaders, Elders of their Central (Lead), Bishopric, and Family Ministries; their Deacons, in charge of production of an endless variety of goods; their Trustees, in charge of their financial affairs. Thus these manuscripts - Ministerial and Family journals, yearbooks, diaries, Covenants, hymnals, are invaluable documents illuminating the concepts and views of Shakers on their religion, theology, music, spiritual life and visions, and their concerns and activities in community organization, membership, daily events, production of goods, financial transactions between Shaker societies and the outside world, their crafts and industries. For information pertaining to specific communities and Shaker individuals, only reference works that were most frequently used are listed: Index of Hancock Shakers - Biographical References, by Priscilla Brewer; Shaker Cities of Peace, Love, and Union: A History of the Hancock Bishopric, by Deborah E. -

Collection Summary Selected Search Terms

Collection Summary ID Number: CS 657 Title: Shakers Extent: 33 Folder(s), 1 Media Item, 4 Map Case Items Span Dates: 1803-2013 Language: English Geographic Location: Various Abstract: This collection consists of newsletters, newspapers, publications, articles, events and museum news from several Shaker communities and historic sites. It also contains the Roger Hall/Shaker Music collection which consists of booklets and recordings of Shaker Music and interviews from 2004 to 2011. Photographs of the communities can be found at: http://digitalarchives.usi.edu/digital/collection/CSIC/search/searchterm/shakers Selected Search Terms Subjects: Communal living; Collective settlements; Housing, Cooperative; Collective farms; Commune; Utopian socialism; Christian life; Christian ethics; Christian stewardship; Shakers; Shakers—Hymns; Sacred music Historical Notes: No other communal group in the United States has endured as long as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, popular known as Shakers, and few have been better known. The Shakers were founded in England; the early members journeyed to colonial America in 1774 under the leadership of Ann Lee and began to develop structured communal life soon thereafter in a first colony at Niskeyuna (later called Watervliet), New York. Shakers lived sober and celibate lives that followed strict rules, including stringent separation of the sexes. For many years they suffered derision and active opposition from detractors—who accused the leaders of exploiting their rank and file members and ridiculed the Shakers for believing that Ann Lee represented Christ in the Second Coming—but eventually positive images displaced the negative ones. The Shakers became known for their vibrant worship services that featured dance-like rituals known as “laboring,” as well as for their fine agricultural products, their simple but elegant architecture and exquisite furniture, and their placement of women in leadership roles. -

2021 Live Auction Preview

2021 LIVE AUCTION PREVIEW Hancock Shaker Village Can’t make the gala on August 14 but want to bid and support the cause? You can place an absentee bid by filling out this form, emailing us here or calling us 413.443.0188, x203. All pre-gala bids must be received by 10am on Saturday, August 14. 1. SHAKER LITHOGRAPH, 1988 John Stritch Signed and numbered 16/100, framed, 25” x 35” John Stritch was a well-known steel abstract expressionist, poster designer and print maker. Born in 1925, Dr. Stritch began his career as a flight surgeon during World War II, and eventually moved to Hinsdale to take up painting and sculpting full-time. He taught students from the Pittsfield Public Schools to the DeSisto School, where he was also the school doctor. Prolific, he designed beautiful poster and serigraphs that recorded the visual beauty of Berkshire cultural icons, most notably and often for Tanglewood, and the posters have become highly collectible following his passing in 2014. Stritch prints were meticulously hand-pulled using a silkscreen on large format heavyweight cotton rag paper, featuring an exquisite blending of color that evinces a sense of precision. What could be more iconic than a Shaker revolving chair? His work is in the collections of the Berkshire Museum, Williams College Museum of Art, and other institutions. Estimated value: $1,000 2. GIFT DRAWING, 2021 Allison Smith Letterpress print with watercolor overlay, signed, limited edition, unframed, 15” x 20” Just north of Hancock Shaker Village is the Shaker Trail, a hike to Mount Sinai. -

NBMAA Anything but Simple Press Release

The New Britain Museum of American Art Presents Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them August 6, 2020-January 10, 2021 NEW BRITAIN, CONN., August 3, 2020, As a part of the 2020/20+ Women @ NBMAA initiative, The New Britain Museum of American Art (NBMAA) is thrilled to present Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them, August 6, 2020 through January 10, 2021. Organized by Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA, Anything but Simple features rare Shaker “gift” or “spirit” drawings created by Shaker women in the mid-1800s, a period known as the Era of Manifestations. During that time, members of Shaker society created dances, songs, and drawings inspired by spiritual revelations or supernatural “gifts.” Colorful, decorative, and complex, “gift” drawings expressed messages of love, dedication to Shaker belief, and the promise of heaven following the earthly journey. Anything but Simple presents 25 of the 200 gift drawings extant in public and private collections today. This group of drawings, made between 1843 and 1857, is widely considered one of the world’s finest collections and includes the most famous gift drawing in existence: Hannah Cohoon’s 1854 Tree of Life. The Shaker Soul The drawings were made by young Shaker women dubbed “instruments” by their elders due to the fact that the women claimed they received these images as gifts from the spirit world. It is perhaps not surprising that a religion founded by a woman should find significant spiritual messages coming from women, even a century before women won the right to vote in the United States. -

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community Elizabeth Shaver Illustrations by Elizabeth Lee PUBLISHED BY THE SHAKER HERITAGE SOCIETY 25 MEETING HOUSE ROAD ALBANY, N. Y. 12211 www.shakerheritage.org MARCH, 1986 UPDATED APRIL, 2020 A is For Apple 3 Preface to 2020 Edition Just south of the Albany International called Watervliet, in 1776. Having fled Airport, Heritage Lane bends as it turns from persecution for their religious beliefs from Ann Lee Pond and continues past an and practices, the small group in Albany old cemetery. Between the pond and the established the first of what would cemetery is an area of trees, and a glance eventually be a network of 22 communities reveals that they are distinct from those in the Northeast and Midwest United growing in a natural, haphazard fashion in States. The Believers, as they called the nearby Nature Preserve. Evenly spaced themselves, had broken away from the in rows that are still visible, these are apple Quakers in Manchester, England in the trees. They are the remains of an orchard 1750s. They had radical ideas for the time: planted well over 200 years ago. the equality of men and women and of all races, adherence to pacifism, a belief that Both the pond, which once served as a mill celibacy was the only way to achieve a pure pond, and this orchard were created and life and salvation, the confession of sins, a tended by the people who now rest in the devotion to work and collaboration as a adjacent cemetery, which dates from 1785. -

Community, Equality, Simplicity, and Charity the Hancock Shaker Village

Community, equality, simplicity, and charity Studying and visiting various forms of religion gives one a better insight to the spiritual, philosophical, physical, cultural, social, and psychological understanding about human behavior and the lifestyle of a particular group. This photo program is about the Hancock Shaker Village, a National Historic Landmark in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The Village includes 20 historic buildings on 750 acres. The staff provide guests with a great deal of insight to the spiritual practices and life among the people called Shakers. Their famous round stone barn is a major attraction at the Village. It is a marvelous place to learn about Shaker life. BACKGROUND “The Protestant Reformation and technological advances led to new Christian sects outside of the Catholic Church and mainstream Protestant denominations into the 17th and 18th centuries. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, commonly known as the Shakers, was a Protestant sect founded in England in 1747. The French Camisards and the Quakers, two Protestant denominations, both contributed to the formation of Shaker beliefs.” <nps.gov/articles/history-of-the-shakers.htm> “In 1758 Ann Lee joined a sect of Quakers, known as the Shakers, that had been heavily influenced by Camisard preachers. In 1770 she was imprisoned in Manchester for her religious views. During her brief imprisonment, she received several visions from God. Upon her release she became known as “Mother Ann.” “In 1772 Mother Ann received another vision from God in the form of a tree. It communicated that a place had been prepared for she and her followers in America. -

Shaker Seminar 2007: South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 1 Number 4 Pages 147-149 October 2007 Shaker Seminar 2007: South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky Christian Goodwillie Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Goodwillie: Shaker Seminar 2007 Shaker Seminar 2007 South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky by Christian Goodwillie The 33rd annual Shaker Seminar took participants to the museums at South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky. These two sites are always a favorite destination for Seminar participants. The friendly people, natural scenery, wonderful Shaker buildings, and outstanding cuisine all add up to an experience unique to Kentucky. The Seminar convened at South Union on July 25, 2007, which marked the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Shaker community at South Union. Participants arrived at the 1869 Tavern constructed by the Shakers for passengers on the Louisville-Nashville railroad. Innkeeper JoAnn Moody prepared an outstanding dinner, setting a standard she repeatedly met while the Seminar was in town. Later in the evening at the 1824 Centre House, South Union’s director Tommy Hines welcomed participants with a fascinating presentation tracing the history of the site from pre-Shaker days right up to the present. The meeting room of the Centre House had a special feeling that night. Of particular interest in Hines’s talk were the new acquisitions to the collection at South Union. -

Shaker Trail Guide

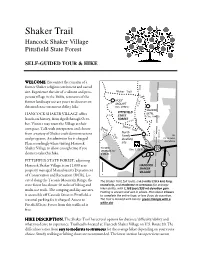

Shaker Trail Hancock Shaker Village Pittsfield State Forest SELF-GUIDED TOUR & HIKE WELCOMEWELCOME. Encounter the remains of a former Shaker religious settlement and sacred site. Experience the site of a vibrant and pros- Shaker Trail Trail perous village in the 1800s, remnants of the HOLY former landscape use are yours to discover on C C. MOUNT . C this moderate-strenuous ability hike. Elev. 1930 ft. SHAKER PITTSFIELD HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE offers MTN. STATE Elev. 1845 ft. hands-on history, from April through Octo- FOREST ber. Visitors may roam the Village at their S B haker rook own pace. Talk with interpreters and choose Tra il D K L North C E T I from a variety of Shaker craft demonstrations O r F a TO Family C il S T N PITTSFIELD dwelling T and programs. An admission fee is charged. A I H 4.6 MILES Plan accordingly when visiting Hancock site P TO NEW Shaker Village to allow enough time if you Elev. 1185 ft. 20 LEBANON, NY desire to take this hike. 6 MILES PITTSFIELD STATE FOREST, adjoining 41 Hancock Shaker Village, is an 11,000 acre HANCOCK SHAKER property managed Massachusetts Department VILLAGE of Conservation and Recreation (DCR). Lo- cated along the Taconic Mountain Range, the The Shaker Trail, full route, is 6.5 miles (10.5 km) long, state forest has almost 40 miles of hiking and round-trip, and moderate to strenuous for average hiker ability, with 1,165 foot (355 m) elevation gain . multi-use trails. The camping and day-use area Footing is uneven and wet in places. -

![FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [Digital Images Attached] PRESS CONTACT: PITTSFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS, May 24, 2021 – Hancock Shaker Villag](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5957/for-immediate-release-digital-images-attached-press-contact-pittsfield-massachusetts-may-24-2021-hancock-shaker-villag-2945957.webp)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [Digital Images Attached] PRESS CONTACT: PITTSFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS, May 24, 2021 – Hancock Shaker Villag

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [Digital images attached] PRESS CONTACT: Carolyn McDaniel [email protected] 413.443.0188 x221 HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE ANNOUNCES OPENING OF NEW RESTAURANT: BIMI’S CAFÉ OPENING MAY 28, 2021 PITTSFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS, May 24, 2021 – Hancock Shaker Village announced today that it has partnered with restaurant entrepreneurs Ellen Waggett and Christopher Landy to open Bimi’s Café at Hancock Shaker Village with Chef Joshua Kelly on Friday, May 28. Farm-to-table has become a cliché, but at the Village it’s actually true, where the farm is a stone’s throw from the kitchen door. Bimi’s Café, serving locally sourced freshly prepared foods and espresso drinks, is owned and operated by the television production and lighting designer husband and wife team Christopher Landy and Ellen Waggett. A shared passion for delicious food, authentic experience, and exceptional service brought Landy and Waggett to Hancock Shaker Village, where diners can walk the farm’s trails where some of the café’s ingredients will be harvested from the Village, which is a museum as well as the oldest working farm in the region. “The mission and vision of Bimi’s,” said Jennifer Trainer Thompson, Director of Hancock Shaker Village, “as well Ellen and Chris’ passion for locally sourced high-quality ingredients, are so much a part of what we do here. We are the farm in farm to table – so of course we want the table too. We’re tremendously excited that Chef Josh will be bringing his considerable talents to the Village.” Open when the museum is open, including evenings when there are concerts and other public events, Bimi’s Café at Hancock Shaker Village will provide a new exciting culinary option for museum and evening visitors, as well as those who live and work locally. -

The Shaker Village

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Christian Denominations and Sects Religion 2008 The Shaker Village Raymond Bial Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bial, Raymond, "The Shaker Village" (2008). Christian Denominations and Sects. 6. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_christian_denominations_and_sects/6 THE SHAKER VILLAGE This page intentionally left blank THE SHAKER VILLAGE RAYMOND BlAL 'fUh UNIVEJ? ITY] Ph OJ.' K]~NTU KY Copyright © 2008 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Conunonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 1211 100908 543 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bial, Raymond. The Shaker village / Raymond Bial. - [Rev. ed.]. p. cm. Rev. ed. of: Shaker home. 1994. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8131-2489-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) 1. Shakers - United States - Juvenile literature. I. Bial, Raymond. Shaker home. II. Title. BX9784.B53 2008 289'.8 - dc22 2007043579 The Shaker Village is lovingly dedicated to my wife, Linda, and my children, Anna, Sarah, and Luke, who accompanied me in making photographs for this book.