Starting SCF Calculations by Superposition of Atomic Densities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Information

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for RSC Advances. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020 Supporting Information How to Select Ionic Liquids as Extracting Agent Systematically? Special Case Study for Extractive Denitrification Process Shurong Gaoa,b,c,*, Jiaxin Jina,b, Masroor Abroc, Ruozhen Songc, Miao Hed, Xiaochun Chenc,* a State Key Laboratory of Alternate Electrical Power System with Renewable Energy Sources, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, 102206, China b Research Center of Engineering Thermophysics, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, 102206, China c Beijing Key Laboratory of Membrane Science and Technology & College of Chemical Engineering, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing 100029, PR China d Office of Laboratory Safety Administration, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing 100124, China * Corresponding author, Tel./Fax: +86-10-6443-3570, E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 1 COSMO-RS Computation COSMOtherm allows for simple and efficient processing of large numbers of compounds, i.e., a database of molecular COSMO files; e.g. the COSMObase database. COSMObase is a database of molecular COSMO files available from COSMOlogic GmbH & Co KG. Currently COSMObase consists of over 2000 compounds including a large number of industrial solvents plus a wide variety of common organic compounds. All compounds in COSMObase are indexed by their Chemical Abstracts / Registry Number (CAS/RN), by a trivial name and additionally by their sum formula and molecular weight, allowing a simple identification of the compounds. We obtained the anions and cations of different ILs and the molecular structure of typical N-compounds directly from the COSMObase database in this manuscript. -

GROMACS: Fast, Flexible, and Free

GROMACS: Fast, Flexible, and Free DAVID VAN DER SPOEL,1 ERIK LINDAHL,2 BERK HESS,3 GERRIT GROENHOF,4 ALAN E. MARK,4 HERMAN J. C. BERENDSEN4 1Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University, Husargatan 3, Box 596, S-75124 Uppsala, Sweden 2Stockholm Bioinformatics Center, SCFAB, Stockholm University, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden 3Max-Planck Institut fu¨r Polymerforschung, Ackermannweg 10, D-55128 Mainz, Germany 4Groningen Biomolecular Sciences and Biotechnology Institute, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, NL-9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands Received 12 February 2005; Accepted 18 March 2005 DOI 10.1002/jcc.20291 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). Abstract: This article describes the software suite GROMACS (Groningen MAchine for Chemical Simulation) that was developed at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands, in the early 1990s. The software, written in ANSI C, originates from a parallel hardware project, and is well suited for parallelization on processor clusters. By careful optimization of neighbor searching and of inner loop performance, GROMACS is a very fast program for molecular dynamics simulation. It does not have a force field of its own, but is compatible with GROMOS, OPLS, AMBER, and ENCAD force fields. In addition, it can handle polarizable shell models and flexible constraints. The program is versatile, as force routines can be added by the user, tabulated functions can be specified, and analyses can be easily customized. Nonequilibrium dynamics and free energy determinations are incorporated. Interfaces with popular quantum-chemical packages (MOPAC, GAMES-UK, GAUSSIAN) are provided to perform mixed MM/QM simula- tions. The package includes about 100 utility and analysis programs. -

![Automated Construction of Quantum–Classical Hybrid Models Arxiv:2102.09355V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 18 Feb 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7378/automated-construction-of-quantum-classical-hybrid-models-arxiv-2102-09355v1-physics-chem-ph-18-feb-2021-177378.webp)

Automated Construction of Quantum–Classical Hybrid Models Arxiv:2102.09355V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 18 Feb 2021

Automated construction of quantum{classical hybrid models Christoph Brunken and Markus Reiher∗ ETH Z¨urich, Laboratorium f¨urPhysikalische Chemie, Vladimir-Prelog-Weg 2, 8093 Z¨urich, Switzerland February 18, 2021 Abstract We present a protocol for the fully automated construction of quantum mechanical-(QM){ classical hybrid models by extending our previously reported approach on self-parametri- zing system-focused atomistic models (SFAM) [J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (3), 1646{1665]. In this QM/SFAM approach, the size and composition of the QM region is evaluated in an automated manner based on first principles so that the hybrid model describes the atomic forces in the center of the QM region accurately. This entails the au- tomated construction and evaluation of differently sized QM regions with a bearable com- putational overhead that needs to be paid for automated validation procedures. Applying SFAM for the classical part of the model eliminates any dependence on pre-existing pa- rameters due to its system-focused quantum mechanically derived parametrization. Hence, QM/SFAM is capable of delivering a high fidelity and complete automation. Furthermore, since SFAM parameters are generated for the whole system, our ansatz allows for a con- venient re-definition of the QM region during a molecular exploration. For this purpose, a local re-parametrization scheme is introduced, which efficiently generates additional clas- sical parameters on the fly when new covalent bonds are formed (or broken) and moved to the classical region. arXiv:2102.09355v1 [physics.chem-ph] 18 Feb 2021 ∗Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] 1 1 Introduction In contrast to most protocols of computational quantum chemistry that consider isolated molecules, chemical processes can take place in a vast variety of complex environments. -

Parameterizing a Novel Residue

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Luthey-Schulten Group, Department of Chemistry Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group Computational Biophysics Workshop Parameterizing a Novel Residue Rommie Amaro Brijeet Dhaliwal Zaida Luthey-Schulten Current Editors: Christopher Mayne Po-Chao Wen February 2012 CONTENTS 2 Contents 1 Biological Background and Chemical Mechanism 4 2 HisH System Setup 7 3 Testing out your new residue 9 4 The CHARMM Force Field 12 5 Developing Topology and Parameter Files 13 5.1 An Introduction to a CHARMM Topology File . 13 5.2 An Introduction to a CHARMM Parameter File . 16 5.3 Assigning Initial Values for Unknown Parameters . 18 5.4 A Closer Look at Dihedral Parameters . 18 6 Parameter generation using SPARTAN (Optional) 20 7 Minimization with new parameters 32 CONTENTS 3 Introduction Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a powerful scientific tool used to study a wide variety of systems in atomic detail. From a standard protein simulation, to the use of steered molecular dynamics (SMD), to modelling DNA-protein interactions, there are many useful applications. With the advent of massively parallel simulation programs such as NAMD2, the limits of computational anal- ysis are being pushed even further. Inevitably there comes a time in any molecular modelling scientist’s career when the need to simulate an entirely new molecule or ligand arises. The tech- nique of determining new force field parameters to describe these novel system components therefore becomes an invaluable skill. Determining the correct sys- tem parameters to use in conjunction with the chosen force field is only one important aspect of the process. -

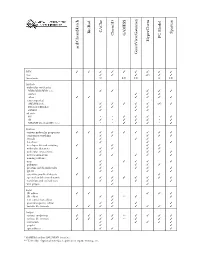

D:\Doc\Workshops\2005 Molecular Modeling\Notebook Pages\Software Comparison\Summary.Wpd

CAChe BioRad Spartan GAMESS Chem3D PC Model HyperChem acd/ChemSketch GaussView/Gaussian WIN TTTT T T T T T mac T T T (T) T T linux/unix U LU LU L LU Methods molecular mechanics MM2/MM3/MM+/etc. T T T T T Amber T T T other TT T T T T semi-empirical AM1/PM3/etc. T T T T T (T) T Extended Hückel T T T T ZINDO T T T ab initio HF * * T T T * T dft T * T T T * T MP2/MP4/G1/G2/CBS-?/etc. * * T T T * T Features various molecular properties T T T T T T T T T conformer searching T T T T T crystals T T T data base T T T developer kit and scripting T T T T molecular dynamics T T T T molecular interactions T T T T movies/animations T T T T T naming software T nmr T T T T T polymers T T T T proteins and biomolecules T T T T T QSAR T T T T scientific graphical objects T T spectral and thermodynamic T T T T T T T T transition and excited state T T T T T web plugin T T Input 2D editor T T T T T 3D editor T T ** T T text conversion editor T protein/sequence editor T T T T various file formats T T T T T T T T Output various renderings T T T T ** T T T T various file formats T T T T ** T T T animation T T T T T graphs T T spreadsheet T T T * GAMESS and/or GAUSSIAN interface ** Text only. -

![Modern Quantum Chemistry with [Open]Molcas](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4742/modern-quantum-chemistry-with-open-molcas-744742.webp)

Modern Quantum Chemistry with [Open]Molcas

Modern quantum chemistry with [Open]Molcas Cite as: J. Chem. Phys. 152, 214117 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004835 Submitted: 17 February 2020 . Accepted: 11 May 2020 . Published Online: 05 June 2020 Francesco Aquilante , Jochen Autschbach , Alberto Baiardi , Stefano Battaglia , Veniamin A. Borin , Liviu F. Chibotaru , Irene Conti , Luca De Vico , Mickaël Delcey , Ignacio Fdez. Galván , Nicolas Ferré , Leon Freitag , Marco Garavelli , Xuejun Gong , Stefan Knecht , Ernst D. Larsson , Roland Lindh , Marcus Lundberg , Per Åke Malmqvist , Artur Nenov , Jesper Norell , Michael Odelius , Massimo Olivucci , Thomas B. Pedersen , Laura Pedraza-González , Quan M. Phung , Kristine Pierloot , Markus Reiher , Igor Schapiro , Javier Segarra-Martí , Francesco Segatta , Luis Seijo , Saumik Sen , Dumitru-Claudiu Sergentu , Christopher J. Stein , Liviu Ungur , Morgane Vacher , Alessio Valentini , and Valera Veryazov J. Chem. Phys. 152, 214117 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004835 152, 214117 © 2020 Author(s). The Journal ARTICLE of Chemical Physics scitation.org/journal/jcp Modern quantum chemistry with [Open]Molcas Cite as: J. Chem. Phys. 152, 214117 (2020); doi: 10.1063/5.0004835 Submitted: 17 February 2020 • Accepted: 11 May 2020 • Published Online: 5 June 2020 Francesco Aquilante,1,a) Jochen Autschbach,2,b) Alberto Baiardi,3,c) Stefano Battaglia,4,d) Veniamin A. Borin,5,e) Liviu F. Chibotaru,6,f) Irene Conti,7,g) Luca De Vico,8,h) Mickaël Delcey,9,i) Ignacio Fdez. Galván,4,j) Nicolas Ferré,10,k) Leon Freitag,3,l) Marco Garavelli,7,m) Xuejun Gong,11,n) Stefan Knecht,3,o) Ernst D. Larsson,12,p) Roland Lindh,4,q) Marcus Lundberg,9,r) Per Åke Malmqvist,12,s) Artur Nenov,7,t) Jesper Norell,13,u) Michael Odelius,13,v) Massimo Olivucci,8,14,w) Thomas B. -

Benchmarking and Application of Density Functional Methods In

BENCHMARKING AND APPLICATION OF DENSITY FUNCTIONAL METHODS IN COMPUTATIONAL CHEMISTRY by BRIAN N. PAPAS (Under Direction the of Henry F. Schaefer III) ABSTRACT Density Functional methods were applied to systems of chemical interest. First, the effects of integration grid quadrature choice upon energy precision were documented. This was done through application of DFT theory as implemented in five standard computational chemistry programs to a subset of the G2/97 test set of molecules. Subsequently, the neutral hydrogen-loss radicals of naphthalene, anthracene, tetracene, and pentacene and their anions where characterized using five standard DFT treatments. The global and local electron affinities were computed for the twelve radicals. The results for the 1- naphthalenyl and 2-naphthalenyl radicals were compared to experiment, and it was found that B3LYP appears to be the most reliable functional for this type of system. For the larger systems the predicted site specific adiabatic electron affinities of the radicals are 1.51 eV (1-anthracenyl), 1.46 eV (2-anthracenyl), 1.68 eV (9-anthracenyl); 1.61 eV (1-tetracenyl), 1.56 eV (2-tetracenyl), 1.82 eV (12-tetracenyl); 1.93 eV (14-pentacenyl), 2.01 eV (13-pentacenyl), 1.68 eV (1-pentacenyl), and 1.63 eV (2-pentacenyl). The global minimum for each radical does not have the same hydrogen removed as the global minimum for the analogous anion. With this in mind, the global (or most preferred site) adiabatic electron affinities are 1.37 eV (naphthalenyl), 1.64 eV (anthracenyl), 1.81 eV (tetracenyl), and 1.97 eV (pentacenyl). In later work, ten (scandium through zinc) homonuclear transition metal trimers were studied using one DFT 2 functional. -

Computational Studies on Carbohydrates: I. Density Functional Ab Initio Geometry Optimization on Maltose Conformations

Computational Studies on Carbohydrates: I. Density Functional Ab Initio Geometry Optimization on Maltose Conformations F. A. MOMANY, J. L. WILLETT Plant Polymer Research, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, 1815 N. University St., Peoria, Illinois 61604 Received 10 September 1999; accepted 10 May 2000 ABSTRACT: Ab initio geometry optimization was carried out on 10 selected conformations of maltose and two 2-methoxytetrahydropyran conformations using the density functional denoted B3LYP combined with two basis sets. The 6-31G∗ and 6-311CCG∗∗ basis sets make up the B3LYP/6-31G∗ and B3LYP/6-311CCG∗∗ procedures. Internal coordinates were fully relaxed, and structures were gradient optimized at both levels of theory. Ten conformations were studied at the B3LYP/6-31G∗ level, and five of these were continued with ∗∗ full gradient optimization at the B3LYP/6-311CCG level of theory. The details of the ab initio optimized geometries are presented here, with particular attention given to the positions of the atoms around the anomeric center and the effect of the particular anomer and hydrogen bonding pattern on the maltose ring structures and relative conformational energies. The size and complexity of the hydrogen-bonding network prevented a rigorous search of conformational space by ab initio calculations. However, using empirical force fields, low-energy conformers of maltose were found that were subsequently gradient optimized at the two ab initio levels of theory. Three classes of conformations were studied, as defined by the clockwise or counterclockwise direction of the hydroxyl groups, or a flipped conformer in which the -dihedral is rotated by ∼180◦.Different combinations of ! side-chain rotations gave energy differences of more than 6 kcal/mol above the lowest energy structure found. -

Jaguar 5.5 User Manual Copyright © 2003 Schrödinger, L.L.C

Jaguar 5.5 User Manual Copyright © 2003 Schrödinger, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Schrödinger, FirstDiscovery, Glide, Impact, Jaguar, Liaison, LigPrep, Maestro, Prime, QSite, and QikProp are trademarks of Schrödinger, L.L.C. MacroModel is a registered trademark of Schrödinger, L.L.C. To the maximum extent permitted by applicable law, this publication is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind. This publication may contain trademarks of other companies. October 2003 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction.......................................................................................1 1.1 Conventions Used in This Manual.......................................................................2 1.2 Citing Jaguar in Publications ...............................................................................3 Chapter 2: The Maestro Graphical User Interface...........................................5 2.1 Starting Maestro...................................................................................................5 2.2 The Maestro Main Window .................................................................................7 2.3 Maestro Projects ..................................................................................................7 2.4 Building a Structure.............................................................................................9 2.5 Atom Selection ..................................................................................................10 2.6 Toolbar Controls ................................................................................................11 -

Visualization and Analysis of Petascale Molecular Simulations with VMD John E

S4410: Visualization and Analysis of Petascale Molecular Simulations with VMD John E. Stone Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/gpu/ S4410, GPU Technology Conference 15:30-16:20, Room LL21E, San Jose Convention Center, San Jose, CA, Tuesday March 25, 2014 Biomedical Technology Research Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Beckman Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign - www.ks.uiuc.edu VMD – “Visual Molecular Dynamics” • Visualization and analysis of: – molecular dynamics simulations – particle systems and whole cells – cryoEM densities, volumetric data – quantum chemistry calculations – sequence information • User extensible w/ scripting and plugins Whole Cell Simulation MD Simulations • http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/ CryoEM, Cellular Biomedical Technology Research Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics SequenceBeckman Data Institute, University of Illinois at QuantumUrbana-Champaign Chemistry - www.ks.uiuc.edu Tomography Goal: A Computational Microscope Study the molecular machines in living cells Ribosome: target for antibiotics Poliovirus Biomedical Technology Research Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Beckman Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign - www.ks.uiuc.edu VMD Interoperability Serves Many Communities • VMD 1.9.1 user statistics: – 74,933 unique registered users from all over the world • Uniquely interoperable -

A Summary of ERCAP Survey of the Users of Top Chemistry Codes

A survey of codes and algorithms used in NERSC chemical science allocations Lin-Wang Wang NERSC System Architecture Team Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory We have analyzed the codes and their usages in the NERSC allocations in chemical science category. This is done mainly based on the ERCAP NERSC allocation data. While the MPP hours are based on actually ERCAP award for each account, the time spent on each code within an account is estimated based on the user’s estimated partition (if the user provided such estimation), or based on an equal partition among the codes within an account (if the user did not provide the partition estimation). Everything is based on 2007 allocation, before the computer time of Franklin machine is allocated. Besides the ERCAP data analysis, we have also conducted a direct user survey via email for a few most heavily used codes. We have received responses from 10 users. The user survey not only provide us with the code usage for MPP hours, more importantly, it provides us with information on how the users use their codes, e.g., on which machine, on how many processors, and how long are their simulations? We have the following observations based on our analysis. (1) There are 48 accounts under chemistry category. This is only second to the material science category. The total MPP allocation for these 48 accounts is 7.7 million hours. This is about 12% of the 66.7 MPP hours annually available for the whole NERSC facility (not accounting Franklin). The allocation is very tight. The majority of the accounts are only awarded less than half of what they requested for. -

Porting the DFT Code CASTEP to Gpgpus

Porting the DFT code CASTEP to GPGPUs Toni Collis [email protected] EPCC, University of Edinburgh CASTEP and GPGPUs Outline • Why are we interested in CASTEP and Density Functional Theory codes. • Brief introduction to CASTEP underlying computational problems. • The OpenACC implementation http://www.nu-fuse.com CASTEP: a DFT code • CASTEP is a commercial and academic software package • Capable of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and plane wave basis set calculations. • Calculates the structure and motions of materials by the use of electronic structure (atom positions are dictated by their electrons). • Modern CASTEP is a re-write of the original serial code, developed by Universities of York, Durham, St. Andrews, Cambridge and Rutherford Labs http://www.nu-fuse.com CASTEP: a DFT code • DFT/ab initio software packages are one of the largest users of HECToR (UK national supercomputing service, based at University of Edinburgh). • Codes such as CASTEP, VASP and CP2K. All involve solving a Hamiltonian to explain the electronic structure. • DFT codes are becoming more complex and with more functionality. http://www.nu-fuse.com HECToR • UK National HPC Service • Currently 30- cabinet Cray XE6 system – 90,112 cores • Each node has – 2×16-core AMD Opterons (2.3GHz Interlagos) – 32 GB memory • Peak of over 800 TF and 90 TB of memory http://www.nu-fuse.com HECToR usage statistics Phase 3 statistics (Nov 2011 - Apr 2013) Ab initio codes (VASP, CP2K, CASTEP, ONETEP, NWChem, Quantum Espresso, GAMESS-US, SIESTA, GAMESS-UK, MOLPRO) GS2NEMO ChemShell 2%2% SENGA2% 3% UM Others 4% 34% MITgcm 4% CASTEP 4% GROMACS 6% DL_POLY CP2K VASP 5% 8% 19% http://www.nu-fuse.com HECToR usage statistics Phase 3 statistics (Nov 2011 - Apr 2013) 35% of the Chemistry software on HECToR is using DFT methods.