Modern Quantum Chemistry with [Open]Molcas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Automated Construction of Quantum–Classical Hybrid Models Arxiv:2102.09355V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 18 Feb 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7378/automated-construction-of-quantum-classical-hybrid-models-arxiv-2102-09355v1-physics-chem-ph-18-feb-2021-177378.webp)

Automated Construction of Quantum–Classical Hybrid Models Arxiv:2102.09355V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 18 Feb 2021

Automated construction of quantum{classical hybrid models Christoph Brunken and Markus Reiher∗ ETH Z¨urich, Laboratorium f¨urPhysikalische Chemie, Vladimir-Prelog-Weg 2, 8093 Z¨urich, Switzerland February 18, 2021 Abstract We present a protocol for the fully automated construction of quantum mechanical-(QM){ classical hybrid models by extending our previously reported approach on self-parametri- zing system-focused atomistic models (SFAM) [J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (3), 1646{1665]. In this QM/SFAM approach, the size and composition of the QM region is evaluated in an automated manner based on first principles so that the hybrid model describes the atomic forces in the center of the QM region accurately. This entails the au- tomated construction and evaluation of differently sized QM regions with a bearable com- putational overhead that needs to be paid for automated validation procedures. Applying SFAM for the classical part of the model eliminates any dependence on pre-existing pa- rameters due to its system-focused quantum mechanically derived parametrization. Hence, QM/SFAM is capable of delivering a high fidelity and complete automation. Furthermore, since SFAM parameters are generated for the whole system, our ansatz allows for a con- venient re-definition of the QM region during a molecular exploration. For this purpose, a local re-parametrization scheme is introduced, which efficiently generates additional clas- sical parameters on the fly when new covalent bonds are formed (or broken) and moved to the classical region. arXiv:2102.09355v1 [physics.chem-ph] 18 Feb 2021 ∗Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] 1 1 Introduction In contrast to most protocols of computational quantum chemistry that consider isolated molecules, chemical processes can take place in a vast variety of complex environments. -

On the Calculation of Molecular Properties of Heavy Element Systems with Ab Initio Approaches: from Gas-Phase to Complex Systems André Severo Pereira Gomes

On the calculation of molecular properties of heavy element systems with ab initio approaches: from gas-phase to complex systems André Severo Pereira Gomes To cite this version: André Severo Pereira Gomes. On the calculation of molecular properties of heavy element systems with ab initio approaches: from gas-phase to complex systems. Theoretical and/or physical chemistry. Universite de Lille, 2016. tel-01960393 HAL Id: tel-01960393 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01960393 Submitted on 19 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. M´emoirepr´esent´epour obtenir le dipl^omed' Habilitation `adiriger des recherches { Sciences Physiques de l'Universit´ede Lille (Sciences et Technologies) ANDRE´ SEVERO PEREIRA GOMES Universit´ede Lille - CNRS Laboratoire PhLAM UMR 8523 On the calculation of molecular properties of heavy element systems with ab initio approaches: from gas-phase to complex systems M´emoirepr´esent´epour obtenir le dipl^omed' Habilitation `adiriger des recherches { Sciences Physiques de l'Universit´ede Lille (Sciences et -

Starting SCF Calculations by Superposition of Atomic Densities

Starting SCF Calculations by Superposition of Atomic Densities J. H. VAN LENTHE,1 R. ZWAANS,1 H. J. J. VAN DAM,2 M. F. GUEST2 1Theoretical Chemistry Group (Associated with the Department of Organic Chemistry and Catalysis), Debye Institute, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands 2CCLRC Daresbury Laboratory, Daresbury WA4 4AD, United Kingdom Received 5 July 2005; Accepted 20 December 2005 DOI 10.1002/jcc.20393 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). Abstract: We describe the procedure to start an SCF calculation of the general type from a sum of atomic electron densities, as implemented in GAMESS-UK. Although the procedure is well known for closed-shell calculations and was already suggested when the Direct SCF procedure was proposed, the general procedure is less obvious. For instance, there is no need to converge the corresponding closed-shell Hartree–Fock calculation when dealing with an open-shell species. We describe the various choices and illustrate them with test calculations, showing that the procedure is easier, and on average better, than starting from a converged minimal basis calculation and much better than using a bare nucleus Hamiltonian. © 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J Comput Chem 27: 926–932, 2006 Key words: SCF calculations; atomic densities Introduction hrstuhl fur Theoretische Chemie, University of Kahrlsruhe, Tur- bomole; http://www.chem-bio.uni-karlsruhe.de/TheoChem/turbo- Any quantum chemical calculation requires properly defined one- mole/),12 GAMESS(US) (Gordon Research Group, GAMESS, electron orbitals. These orbitals are in general determined through http://www.msg.ameslab.gov/GAMESS/GAMESS.html, 2005),13 an iterative Hartree–Fock (HF) or Density Functional (DFT) pro- Spartan (Wavefunction Inc., SPARTAN: http://www.wavefun. -

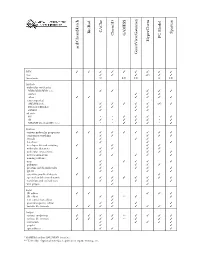

D:\Doc\Workshops\2005 Molecular Modeling\Notebook Pages\Software Comparison\Summary.Wpd

CAChe BioRad Spartan GAMESS Chem3D PC Model HyperChem acd/ChemSketch GaussView/Gaussian WIN TTTT T T T T T mac T T T (T) T T linux/unix U LU LU L LU Methods molecular mechanics MM2/MM3/MM+/etc. T T T T T Amber T T T other TT T T T T semi-empirical AM1/PM3/etc. T T T T T (T) T Extended Hückel T T T T ZINDO T T T ab initio HF * * T T T * T dft T * T T T * T MP2/MP4/G1/G2/CBS-?/etc. * * T T T * T Features various molecular properties T T T T T T T T T conformer searching T T T T T crystals T T T data base T T T developer kit and scripting T T T T molecular dynamics T T T T molecular interactions T T T T movies/animations T T T T T naming software T nmr T T T T T polymers T T T T proteins and biomolecules T T T T T QSAR T T T T scientific graphical objects T T spectral and thermodynamic T T T T T T T T transition and excited state T T T T T web plugin T T Input 2D editor T T T T T 3D editor T T ** T T text conversion editor T protein/sequence editor T T T T various file formats T T T T T T T T Output various renderings T T T T ** T T T T various file formats T T T T ** T T T animation T T T T T graphs T T spreadsheet T T T * GAMESS and/or GAUSSIAN interface ** Text only. -

Kepler Gpus and NVIDIA's Life and Material Science

LIFE AND MATERIAL SCIENCES Mark Berger; [email protected] Founded 1993 Invented GPU 1999 – Computer Graphics Visual Computing, Supercomputing, Cloud & Mobile Computing NVIDIA - Core Technologies and Brands GPU Mobile Cloud ® ® GeForce Tegra GRID Quadro® , Tesla® Accelerated Computing Multi-core plus Many-cores GPU Accelerator CPU Optimized for Many Optimized for Parallel Tasks Serial Tasks 3-10X+ Comp Thruput 7X Memory Bandwidth 5x Energy Efficiency How GPU Acceleration Works Application Code Compute-Intensive Functions Rest of Sequential 5% of Code CPU Code GPU CPU + GPUs : Two Year Heart Beat 32 Volta Stacked DRAM 16 Maxwell Unified Virtual Memory 8 Kepler Dynamic Parallelism 4 Fermi 2 FP64 DP GFLOPS GFLOPS per DP Watt 1 Tesla 0.5 CUDA 2008 2010 2012 2014 Kepler Features Make GPU Coding Easier Hyper-Q Dynamic Parallelism Speedup Legacy MPI Apps Less Back-Forth, Simpler Code FERMI 1 Work Queue CPU Fermi GPU CPU Kepler GPU KEPLER 32 Concurrent Work Queues Developer Momentum Continues to Grow 100M 430M CUDA –Capable GPUs CUDA-Capable GPUs 150K 1.6M CUDA Downloads CUDA Downloads 1 50 Supercomputer Supercomputers 60 640 University Courses University Courses 4,000 37,000 Academic Papers Academic Papers 2008 2013 Explosive Growth of GPU Accelerated Apps # of Apps Top Scientific Apps 200 61% Increase Molecular AMBER LAMMPS CHARMM NAMD Dynamics GROMACS DL_POLY 150 Quantum QMCPACK Gaussian 40% Increase Quantum Espresso NWChem Chemistry GAMESS-US VASP CAM-SE 100 Climate & COSMO NIM GEOS-5 Weather WRF Chroma GTS 50 Physics Denovo ENZO GTC MILC ANSYS Mechanical ANSYS Fluent 0 CAE MSC Nastran OpenFOAM 2010 2011 2012 SIMULIA Abaqus LS-DYNA Accelerated, In Development NVIDIA GPU Life Science Focus Molecular Dynamics: All codes are available AMBER, CHARMM, DESMOND, DL_POLY, GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD Great multi-GPU performance GPU codes: ACEMD, HOOMD-Blue Focus: scaling to large numbers of GPUs Quantum Chemistry: key codes ported or optimizing Active GPU acceleration projects: VASP, NWChem, Gaussian, GAMESS, ABINIT, Quantum Espresso, BigDFT, CP2K, GPAW, etc. -

Benchmarking and Application of Density Functional Methods In

BENCHMARKING AND APPLICATION OF DENSITY FUNCTIONAL METHODS IN COMPUTATIONAL CHEMISTRY by BRIAN N. PAPAS (Under Direction the of Henry F. Schaefer III) ABSTRACT Density Functional methods were applied to systems of chemical interest. First, the effects of integration grid quadrature choice upon energy precision were documented. This was done through application of DFT theory as implemented in five standard computational chemistry programs to a subset of the G2/97 test set of molecules. Subsequently, the neutral hydrogen-loss radicals of naphthalene, anthracene, tetracene, and pentacene and their anions where characterized using five standard DFT treatments. The global and local electron affinities were computed for the twelve radicals. The results for the 1- naphthalenyl and 2-naphthalenyl radicals were compared to experiment, and it was found that B3LYP appears to be the most reliable functional for this type of system. For the larger systems the predicted site specific adiabatic electron affinities of the radicals are 1.51 eV (1-anthracenyl), 1.46 eV (2-anthracenyl), 1.68 eV (9-anthracenyl); 1.61 eV (1-tetracenyl), 1.56 eV (2-tetracenyl), 1.82 eV (12-tetracenyl); 1.93 eV (14-pentacenyl), 2.01 eV (13-pentacenyl), 1.68 eV (1-pentacenyl), and 1.63 eV (2-pentacenyl). The global minimum for each radical does not have the same hydrogen removed as the global minimum for the analogous anion. With this in mind, the global (or most preferred site) adiabatic electron affinities are 1.37 eV (naphthalenyl), 1.64 eV (anthracenyl), 1.81 eV (tetracenyl), and 1.97 eV (pentacenyl). In later work, ten (scandium through zinc) homonuclear transition metal trimers were studied using one DFT 2 functional. -

Charge-Transfer Biexciton Annihilation in a Donor-Acceptor

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Science. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020 Supporting Information for Charge-Transfer Biexciton Annihilation in a Donor-Acceptor Co-crystal yields High-Energy Long-Lived Charge Carriers Itai Schlesinger, Natalia E. Powers-Riggs, Jenna L. Logsdon, Yue Qi, Stephen A. Miller, Roel Tempelaar, Ryan M. Young, and Michael R. Wasielewski* Department of Chemistry and Institute for Sustainability and Energy at Northwestern, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois 60208-3113 Contents 1. Single crystal X-ray structure data. ..................................................................................................2 2. Crystal structure determination and refinement.............................................................................3 3. Additional Steady-state absorption Spectra.....................................................................................4 4. Pump and probe spot sizes.................................................................................................................5 5. Excitation density and fraction of molecules excited calculations ..................................................6 6. Calculation of the fraction of CT excitons adjacent to one another ...............................................7 7. Calculation of reorganization energies and charge transfer rates..................................................9 8. Model Hamiltonian for calculating polarization-dependent steady-state absorption -

FORCE FIELDS and CRYSTAL STRUCTURE PREDICTION Contents

FORCE FIELDS AND CRYSTAL STRUCTURE PREDICTION Bouke P. van Eijck ([email protected]) Utrecht University (Retired) Department of Crystal and Structural Chemistry Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands Originally written in 2003 Update blind tests 2017 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Lattice Energy 2 2.1 Polarcrystals .............................. 4 2.2 ConvergenceAcceleration . 5 2.3 EnergyMinimization .......................... 6 3 Temperature effects 8 3.1 LatticeVibrations............................ 8 4 Prediction of Crystal Structures 9 4.1 Stage1:generationofpossiblestructures . .... 9 4.2 Stage2:selectionoftherightstructure(s) . ..... 11 4.3 Blindtests................................ 14 4.4 Beyondempiricalforcefields. 15 4.5 Conclusions............................... 17 4.6 Update2017............................... 17 1 1 Introduction Everybody who looks at a crystal structure marvels how Nature finds a way to pack complex molecules into space-filling patterns. The question arises: can we understand such packings without doing experiments? This is a great challenge to theoretical chemistry. Most work in this direction uses the concept of a force field. This is just the po- tential energy of a collection of atoms as a function of their coordinates. In principle, this energy can be calculated by quantumchemical methods for a free molecule; even for an entire crystal computations are beginning to be feasible. But for nearly all work a parameterized functional form for the energy is necessary. An ab initio force field is derived from the abovementioned calculations on small model systems, which can hopefully be generalized to other related substances. This is a relatively new devel- opment, and most force fields are empirical: they have been developed to reproduce observed properties as well as possible. There exists a number of more or less time- honored force fields: MM3, CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS, DREIDING.. -

![Arxiv:1911.06836V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 8 Aug 2019 A](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0105/arxiv-1911-06836v1-physics-chem-ph-8-aug-2019-a-950105.webp)

Arxiv:1911.06836V1 [Physics.Chem-Ph] 8 Aug 2019 A

Multireference electron correlation methods: Journeys along potential energy surfaces Jae Woo Park,1, ∗ Rachael Al-Saadon,2 Matthew K. MacLeod,3 Toru Shiozaki,2, 4 and Bess Vlaisavljevich5, y 1Department of Chemistry, Chungbuk National University, Chungdae-ro 1, Cheongju 28644, Korea. 2Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Rd., Evanston, IL 60208, USA. 3Workday, 4900 Pearl Circle East, Suite 100, Boulder, CO 80301, USA. 4Quantum Simulation Technologies, Inc., 625 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. 5Department of Chemistry, University of South Dakota, 414 E. Clark Street, Vermillion, SD 57069, USA. (Dated: November 19, 2019) Multireference electron correlation methods describe static and dynamical electron correlation in a balanced way, and therefore, can yield accurate and predictive results even when single-reference methods or multicon- figurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) theory fails. One of their most prominent applications in quantum chemistry is the exploration of potential energy surfaces (PES). This includes the optimization of molecular ge- ometries, such as equilibrium geometries and conical intersections, and on-the-fly photodynamics simulations; both depend heavily on the ability of the method to properly explore the PES. Since such applications require the nuclear gradients and derivative couplings, the availability of analytical nuclear gradients greatly improves the utility of quantum chemical methods. This review focuses on the developments and advances made in the past two decades. To motivate the readers, we first summarize the notable applications of multireference elec- tron correlation methods to mainstream chemistry, including geometry optimizations and on-the-fly dynamics. Subsequently, we review the analytical nuclear gradient and derivative coupling theories for these methods, and the software infrastructure that allows one to make use of these quantities in applications. -

Generating Gaussian Basis Sets for CRYSTAL and Qwalk Lucas K

Generating Gaussian basis sets for CRYSTAL and QWalk Lucas K. Wagner The point of a basis set is to describe a (generally unknown) function efficiently. That is, we are going to approximate some general function f(x) by a sum over known basis functions (in this case χ(x)): X f(x) = ciχi(x): (1) i We will usually choose χi(x) such that they are convenient to work with. Perhaps integrals are easy to do with them, or perhaps they very closely approximate the function f(x), so that we don’t need too many elements in the sum of Eqn1. One basis set expansion that you may be familiar with is the Fourier expansion, which uses plane waves as the χi’s. In many-body quantum systems, we typically start our description of the many-body wave function Ψ(r1; r2;:::) with a Slater determinant. This is written as follows: 0 1 φ1(r1) φ1(r2) φ1(r3) ::: B φ2(r1) φ2(r2) φ2(r3) ::: C ΨS(r1; r2;:::) = Det B C (2) @ φ3(r1) φ3(r2) φ3(r3) ::: A :::::::::::: where ri is the position of the ith electron and φi(r) is called a molecular or crystalline orbital (MO/CO). The Slater determinant is the simplest possible many-electron wave function that satisfies fermion antisymmetry [Ψ(r1; r2;:::) = Ψ(r2; r1;:::)]. There also − exist algorithms to evaluate properties of the Slater determinant efficiently. Note that these one-particle functions φi have not yet been specified, and we will have to come up with a way to represent them within the computer. -

A Summary of ERCAP Survey of the Users of Top Chemistry Codes

A survey of codes and algorithms used in NERSC chemical science allocations Lin-Wang Wang NERSC System Architecture Team Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory We have analyzed the codes and their usages in the NERSC allocations in chemical science category. This is done mainly based on the ERCAP NERSC allocation data. While the MPP hours are based on actually ERCAP award for each account, the time spent on each code within an account is estimated based on the user’s estimated partition (if the user provided such estimation), or based on an equal partition among the codes within an account (if the user did not provide the partition estimation). Everything is based on 2007 allocation, before the computer time of Franklin machine is allocated. Besides the ERCAP data analysis, we have also conducted a direct user survey via email for a few most heavily used codes. We have received responses from 10 users. The user survey not only provide us with the code usage for MPP hours, more importantly, it provides us with information on how the users use their codes, e.g., on which machine, on how many processors, and how long are their simulations? We have the following observations based on our analysis. (1) There are 48 accounts under chemistry category. This is only second to the material science category. The total MPP allocation for these 48 accounts is 7.7 million hours. This is about 12% of the 66.7 MPP hours annually available for the whole NERSC facility (not accounting Franklin). The allocation is very tight. The majority of the accounts are only awarded less than half of what they requested for. -

The Molpro Quantum Chemistry Package

The Molpro Quantum Chemistry package Hans-Joachim Werner,1, a) Peter J. Knowles,2, b) Frederick R. Manby,3, c) Joshua A. Black,1, d) Klaus Doll,1, e) Andreas Heßelmann,1, f) Daniel Kats,4, g) Andreas K¨ohn,1, h) Tatiana Korona,5, i) David A. Kreplin,1, j) Qianli Ma,1, k) Thomas F. Miller, III,6, l) Alexander Mitrushchenkov,7, m) Kirk A. Peterson,8, n) Iakov Polyak,2, o) 1, p) 2, q) Guntram Rauhut, and Marat Sibaev 1)Institut f¨ur Theoretische Chemie, Universit¨at Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 55, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 2)School of Chemistry, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom 3)School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock’s Close, Bristol BS8 1TS, United Kingdom 4)Max-Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Heisenbergstraße 1, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 5)Faculty of Chemistry, University of Warsaw, L. Pasteura 1 St., 02-093 Warsaw, Poland 6)Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125, United States 7)MSME, Univ Gustave Eiffel, UPEC, CNRS, F-77454, Marne-la- Vall´ee, France 8)Washington State University, Department of Chemistry, Pullman, WA 99164-4630 1 Molpro is a general purpose quantum chemistry software package with a long devel- opment history. It was originally focused on accurate wavefunction calculations for small molecules, but now has many additional distinctive capabilities that include, inter alia, local correlation approximations combined with explicit correlation, highly efficient implementations of single-reference correlation methods, robust and efficient multireference methods for large molecules, projection embedding and anharmonic vibrational spectra.