Rechanneling Their Passion - Washingtonpost.Com Page 1 of 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

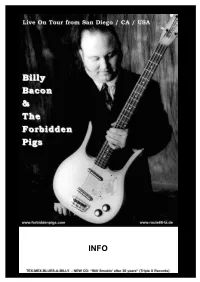

Pigs Bio Engl 2006.Pdf

INFO BILLY BACON Agency & Mailorder PA & Backline Service Steigweg 17 D-88299 Leutkirch AND THE FORBIDDEN PIGS Phone 0049 / (0)7561 / 71161 Fax 0049 / (0) 7561/ 72145 Mobil 0049 / (0)172 / 85 44 201 E-mail [email protected] www.Route66-LA.de Singer/Songwriter and Bassist Billy Bacon founded The Forbidden Pigs in 1984. Their musical gumbo is as unique as their name, drawing roots from all styles of American music. The band's influences are: Jump/Swing, Tex-Mex, Country, Pop and Blues. The "Pigs" as their fans know them are considered "The most versatile band in the land"and play in excess of 200 shows a year coast to coast and overseas. They have released seven full length CD's to date, which are available worldwide. Their newest CD "Pigs At the Zoo" is the soundtrack from the PBS series "Backstage Pass". In the course of their recording history "The Pigs" have played host to a variety of noted guest musicians including Grammy award winning fiddle player Michael Doucet, former James Gang leader and current Eagle, Joe Walsh, Dave Alvin of The Blasters and X fame, Mojo Nixon, Singer/ Songwriting legend Chris Gaffney, Guitar wizard Evan Johns and countless other world class musicians always ready to join in on a "Pig's" recording session. This band has also been featured on several movie and TV soundtracks including MTV and the offbeat hit Red Rock West. However, the main attraction is of course, the live show. A live performance from the "Pigs" can be both rip-roaring and heartfelt at the same time. -

WDAM Radio Presents the Rest of the Story

WDAM Radio Presents The Rest Of The Story # Artist Title Chart Comments Position/Year 0000 Mr. Announcer & The “Introduction/Station WDAM Radio Singers Identification” 0001 Big Mama Thornton “Hound Dog” #1-R&B/1953 0001A Rufus Thomas "Bear Cat" #3-R&B/1953 0001A_ Charlie Gore & Louis “You Ain't Nothin' But A –/1953 Innes Female Hound Dog” 0001AA Romancers “House Cat” –/1955 0001B Elvis Presley “Hound Dog” #1/1956 0001BA Frank (Dual Trumpet) “New Hound Dog” –/1956 Motley & His Crew 0001C Homer & Jethro “Houn’ Dog (Take 2)” –/1956 0001D Pati Palin “Alley Cat” –/1956 0001E Cliff Johnson “Go ‘Way Hound Dog” –/1958 0002 Gary Lewis & The "Count Me In" #2/1965 Playboys 0002A Little Jonna Jaye "I'll Count You In" –/1965 0003 Joanie Sommers "One Boy" #54/1960 0003A Ritchie Dean "One Girl" –/1960 0004 Angels "My Boyfriend's Back" #1/1963 0004A Bobby Comstock & "Your Boyfriend's Back" #98/1963 The Counts 0004AA Denny Rendell “I’m Back Baby” –/1963 0004B Angels "The Guy With The Black Eye" –/1963 0004C Alice Donut "My Boyfriend's Back" –/1990 adult content 0005 Beatles [with Tony "My Bonnie" #26/1964 Sheridan] 0005A Bonnie Brooks "Bring Back My Beatles (To –/1964 Me)" 0006 Beach Boys "California Girls" #3/1965 0006A Cagle & Klender "Ocean City Girls" –/1985 0006B Thomas & Turpin "Marietta Girls" –/1985 0007 Mike Douglas "The Men In My Little Girl's #8/1965 Life" 0007A Fran Allison "The Girls In My Little Boy's –/1965 Life" 0007B Cousin Fescue "The Hoods In My Little Girl's –/1965 Life" 0008 Dawn "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round #1/1973 the Ole Oak Tree" -

Sun.Aug.23.15 195 Songs, 12.3 Hours, 1.47 GB

Page 1 of 6 .Sun.Aug.23.15 195 songs, 12.3 hours, 1.47 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Peaks Song 3:27 Silence Is A Weapon Blackfire 2 I Can't Give You Anything 2:01 Rocket To Russia The Ramones 3 The Cutter 3:50 U2 Jukebox Echo & The Bunnymen 4 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 5 Glad To See You Go 2:12 U2 Jukebox The Ramones 6 Wake Up 5:31 U2 Jukebox The Arcade Fire 7 Grey Will Fade 4:45 U2 Jukebox Charlotte Hatherley 8 Obstacle 1 4:10 U2 Jukebox Interpol 9 Pagan Lovesong 3:27 U2 Jukebox Virgin Prunes 10 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 11 30 Seconds Over Tokyo 6:21 U2 Jukebox Pere Ubu 12 Hounds Of Love 3:02 U2 Jukebox The Futureheads 13 Cattle And Cane 4:14 U2 Jukebox The Go-Betweens 14 A Forest 5:54 U2 Jukebox The Cure 15 The Cutter 3:50 U2 Jukebox Echo & The Bunnymen 16 Christine 2:58 U2 Jukebox Siouxsie & The Banshees 17 Glad To See You Go 2:12 U2 Jukebox The Ramones 18 Tell Me You Love Me 2:33 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 19 Peaches En Regalia 3:37 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 20 Don't Eat The Yellow Snow (Singl… 3:35 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 21 My Guitar Wants To Kill Your Mama 3:32 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 22 COPE-Terry 0:33 23 The Way It Is 2:22 The Strokes 24 Delicious Demon 2:42 Life's Too Good Sugarcubes 25 Tumble In The Rough 3:19 Tiny Music.. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Atom and His Package Possibly the Smallest Band on the List, Atom & His

Atom and His Package Possibly the smallest band on the list, Atom & his Package consists of Adam Goren (Atom) and his package (a Yamaha music sequencer) make funny punk songs utilising many of of the package's hundreds of instruments about the metric system, the lead singer of Judas Priest and what Jewish people do on Christmas. Now moved on to other projects, Atom will remain the person who told the world Anarchy Means That I Litter, The Palestinians Are Not the Same Thing as the Rebel Alliance Jackass, and If You Own The Washington Redskins, You're a ****. Ghost Mice With only two members in this folk/punk band their voices and their music can be heard along with such pride. This band is one of the greatest to come out of the scene because of their abrasive acoustic style. The band consists of a male guitarist (I don't know his name) and Hannah who plays the violin. They are successful and very well should be because it's hard to 99 when you have such little to work with. This band is off Plan It X records and they put on a fantastic show. Not only is the band one of the leaders of the new genre called folk/punk but I'm sure there is going to be very big things to come from them and it will always be from the heart. Defiance, Ohio Defiance, Ohio are perhaps one of the most compassionate and energetic leaders of the "folk/punk" movement. Their clever lyrics accompanied by fast, melodic, acoustic guitars make them very enjoyable to listen to. -

WDAM Radio's History of Elvis Presley

Listeners Guide To WDAM Radio’s History of Elvis Presley This is the most comprehensive collection ever assembled of Elvis Presley’s “charted” hit singles, including the original versions of songs he covered, as well as other artists’ hit covers of songs first recorded by Elvis plus songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis! More than a decade in the making and an ongoing work-in-progress for the coming decades, this collection includes many WDAM Radio exclusives – songs you likely will not find anywhere else on this planet. Some of these, such as the original version of Muss I Denn (later recorded by Elvis as Wooden Heart) and Liebestraum No. 3 later recorded by Elvis as Today, Tomorrow And Forever) were provided by academicians, scholars, and collectors from cylinders or 78s known to be the only copies in the world. Once they heard about this WDAM Radio project, they graciously donated dubs for this archive – with the caveat that they would never be duplicated for commercial use and restricted only to musicologists and scholarly purposes. This collection is divided into four parts: (1) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S singles hits in chronological order – (2) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S and U K singles, the original versions of these songs by other artists, and hit versions by other artists of songs that Elvis Presley recorded first or had a cover hit – in chronological order, along with relevant parody/answer tunes – (3) Songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley – mostly, but not all in chronological order – and (4) X-rated or “adult-themed” songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 9-1987 Wavelength (September 1987) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (September 1987) 83 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/69 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \1'5 NAlCHLY RoLl OVA. \/lC AWO f~·ArqK DAVIS! NAT'L-'(! •• • J-··~ ~!;~ .:.::•\ . •••. ...... ·:·..... ! ~ . .. .. ., .. .. .. .. ... -.. • ..• • .•.. •..•• .... ,. • • • • • • • . .... •• .. • . • .. •. • •. "'•· ~ • •••• •• • • • • • • • •• •••. • • • • • • • • ••••• • • • • • • • # • • • • • • ••• •• •• ••• • • • • • ...... : . •• • .• . • • • •., • . • . .: ' .· .... • • • • . .· .. : . • • • • • • • • • , • • • • • S Nt-131~0817TOL M3N t-Il ~oN~31~0 M3 l.N3l·'~l.~~d3G .::10s Al. I S~3AINn· - N A~~~SI~ NOil.ISin~~t-1 r:· 8NOI • ...·.. 1 1~\73 \ ! .... U.S. BUlK RATE _,.. ,. _... POSTAGE PAID •• _........ Mill~ ,.. J ,, ......... La.l0001 SpecilltiM. InC. - ,,.. ~ BUGlESTWo :~BJi~ST. AMBITIOH AHO R£\IENGE, IN THE AFTERNOON RAYMILLAND THE NATION WAS EMBROILED IN CML WAR, AND THAT MEANT CHOOSING SIDES ...WHETHER YOU WANTED 10 OR NOT: BATON ROUGE: • Veterans at David in Metairie 885-4200 • 8345 Aorida Blvd. at Airline Hwy. 926-6214 "I'm 11 0t sure. but I'm a/molt positil'e. that all music came from .\'ell' Orlea11I." - Ernie K-Doe. 1979 Features Vic 'n' Notly ..... ......... 17 Snooks Eaglin ......... ....23 Bruce Daigrepont . ........24 Austin, Texos ............ ..26 Departments September News . 4 Film . ... .. .......... ... 6 Chomp Report . 8 Caribbean . ................ 1 0 A Copello .... .. ........ .. 12 U.S. Indies .... .. .... .... 1 4 Rare Record .. ............. 1 5 Reviews .. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 7-1986 Wavelength (July 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (July 1986) 69 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/60 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1685 C0550 EARL K. LONG LIBRARY ACQUISITIONS DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS NEW ORLEANS LA 70148 . rRINCC CUnder the - (~CRRY mooN THE FANTASY BEGINS JULY 2 "I'm not sun, but I'm almost positive, tluzt all music ~· came from New Orltans." '· -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features Playing in the Band ............17 New Orleans Bands ...........19 Jim Russell ....................22 Cinemox Dream Taping ....... 24 Departments July News ........... ........ 4 Cabaret ....................... 8 The Law ......................10 Reviews .................... 12 July Listings ...................26 Classified .................. ...29 Last Page ....................30 JHmlberof ~k Plobllshtr. Nau""n S S..'"' Editor. C<>nnoc Zeanah Alk<n«>n. Assorloto FAIItor. Gene S..·aramuun. Art Oindor. TIK'"""' Dnlan Ad>Ortlslna. lilo7abcch F<>nlau~e. E•letn Semcncelli. Ty~nplty. DevluVWcnrcr A'~·.nciate' Contributors, Steve Amll>nl,ccr.lvan Bndk:y. Sc Gc<>fl'C Bryan. BnbCacal••••· R>Ck Culcll\dn, Cioiml Gmady. G1n;~ GI.K.x:- tonc. N;c~ Mannclk>. Bunny Matthew.... Mclnc.ly Manco. Rtck. Oh\·ter. Hammond Scott, Durrc Scrccc. Dc"'CY Wcht> Wm ·t'h·nxth i' puhh,hctJ monthly 1n New ()rlc--..an ... -

Wavelength (April 1986)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1986 Wavelength (April 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1986) 66 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/58 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C0550 ARL K. LONG LIBRARY CQUISITIONS DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS NEW ORLEANS LA 70148 (4\l t. ~ .. ~ PROUD SPONSOR 1986 JAZZ FESTIVAL. ISSUE NO. 66 • APRIL 1986 u/'m not sure. but l'rn almost positive. that all music came from New Orleans ... Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features Aaron Neville .. ............ ...... 23 MADE THE Charles Connor .... ............... 25 Philip Glass ...... ............. ... 28 AMERICAN WAY Departments April News .. ............. ......... 4 Jazz Fest Update .... .............. 7 Boogie Beat Jive .................. 10 Cabaret . ........ ."12 Film...... ................ 14 Caribbean ................ ...... 16 Rock.. .......... ......... 18 U.S. Indies. : . ........ 20 April Listings . ............ 30 Classifieds ....................... 37 Last Page . ....................... 38 COVER OF AARON NEVILLE BY RICO A1tzmberof NetWCSfk Publisher. Nauman S. Sc::on . Editor, Connie Zcanah Atkinson. Associate Editor. Gene Scar.tmuuo. Of'tk« Manager. Diana Rrnoenberg. Art Director. Eric Gemhau\Cr. Typography. Devlin/Wen(!.cr As:-ociates. Advertising. Eli zabeth Fontame. Eileen Sc:mcntelh. Kate Riedl. Contributors. Ivan Bodley. St. Get'fg_t: Bryotn. Bob Catali()l!l, Rick Coleman. Caml Gniady. Gina Gucctone. Ntck Munncllo. Melody Minco. Rick Olivier. Diana Ro:.enberg. Gene Scar amuZL.o. -

ARKANSAS FARMWIFE GIVES BIRTH to ALIEN COW BABY! “He Looks Jes’ Like His Real Momma,” Says the Mother by E

Inside THE GAME THAT’S INVADING HICKSTON ® The Adult Redneck Daily Tuesday, April 1, 1997 25 cents ARKANSAS FARMWIFE GIVES BIRTH TO ALIEN COW BABY! “He looks jes’ like his real momma,” says the mother By E. Price For the Hickston Hog HICKSTON, ARKANSAS — Fact or fiction? A rural sheriff’s wife claims that her infant son is actually the result of alien experi- ments conducted upon herself and her family’s livestock. “Them aliens ‘napped our best cow right before Ah dropped this-here young’un,” claims Bertha-Sue Hobbes of the small Southern town of Hickston. “Ah had dreams ‘bout it at the time,lahke they was checkin’ out mah brain. Ah reckon they was lookin’ fur smarts or somepin’, which explains why they left me ‘n’Lester alone. Ah mean, that Suzie was a damn smart cow. “As for baby Earl here, well, mebbe they sorta beamed cow genny-etic stuff COULD YOUR CHILD BE NEXT? — Scientists say that little Earl Hobbes (above) is "genetically part into me from outer space or somethin’. bovine," but we here at the Hog say hogwash! He's half cow and we all know it! See COW BABY,page 12 cials are unable to explain the mass disap- WE’RE NOT ALONE! DISASTER pearance, which also claimed all livestock larger than poultry. “There are signs of some sort of battle STRIKES SMALL all over town —discarded weapons, ammo shells, small craters, smears of SOUTHERN TOWN blood —but there are no bodies and no signs that any bodies were dragged away,” Local community deserted said Sheriff Parmer of nearby Rabbit under mysterious circustances Ridge. -

The Road Tales from Touring Musicians

THE ROAD TALES FROM TOURING MUSICIANS TONY PATINO COVER ART BY JOSHUA ROTHROCK Copyright © 2012 Tony Patino No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the the author. ISBN-13: 978-1475132649 ISBN-10: 1475132646 second edition paperback June 2012 Editor: Tony Patino Cover art: Joshua Rothrock Cover and interior layout: Tony Patino www.tonypatinosworld.com www.40amp.com [email protected] CONTENTS FORWARD MOJO NIXON solo artist 1 JOHN STANIER helmet, battles 4 TEXAS TERRI texas terri bomb 6 CHRIS GATES the big boys, junkyard 7 BRANDON CRUZ dead kennedys, dr. know 10 WILLIAM WEBER gg allin, the candy snatchers 12 GERRY ATTRIC the bulemics 15 WES TEXAS the bulemics 16 ANIMAL the anti-nowhere league 18 TIM BARRY avail 19 NICKI SICKI verbal abuse 22 RICHIE LAWLER clairmel 24 DAVE DECKER clairmel 26 JOHN KASTNER asexuals, the doughboys 29 SCOTT MCCULLOUGH the doughboys 32 BLAG DAHLIA the dwarves 34 KARL MORRIS the exploited, billyclub 38 JIM COLEMAN cop shoot cop 41 STONEY TOMBS the hookers 42 MIKE WATT the minutemen 43 CHRIS BARROWS pink lincolns 44 TESCO VEE the meatmen 46 NATE WATERS infected 49 TIM LEITCH fear 52 IAN MACKAYE minor threat, fugazi 53 DONNY PAYCHECK zeke 55 GINGER COYOTE white trash debutantes 57 BEN DEILY the lemonheads 58 SAM WILLIAMS down by law 61 FARRELL HOLTZ decry 63 TONY OFFENDER the offenders 65 SAMMYTOWN fang 66 JAMES BROGAN samiam