Download the Full Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009-Fall-Dividend.Pdf

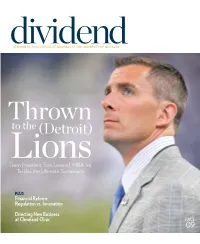

dividendSTEPHEN M. ROSS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Thrown to the (Detroit) Lions Team President Tom Lewand, MBA ’96, Tackles the Ultimate Turnaround PLUS Financial Reform: Regulation vs. Innovation Directing New Business at Cleveland Clinic FALL 09 Solve the RIGHT Problems The Ross Executive MBA Advanced leadership training for high-potential professionals • Intense focus on leadership and strategy • A peer group of proven leaders from many industries across the U.S. • Manageable once-a-month format • Ranked #4 by BusinessWeek* • A globally respected degree • A transformative experience To learn more about the Ross Executive MBA call 734-615-9700 or visit us online at www.bus.umich.edu/emba *2007 Executive MBA TABLEof CONTENTS FALL 09 FEATURES 24 Thrown to the (Detroit) Lions Tom Lewand, AB ’91/MBA/JD ’96, tackles the turn- around job of all time: president of the Detroit Lions. 28 The Heart of the Matter Surgeon Brian Duncan, MBA ’08, brings practical expertise to new business development at Cleveland Clinic. 32 Start Me Up Serial entrepreneur Brad Keywell, BBA ’91/JD ’93, goes from odd man out to man with a plan. Multiple plans, that is. 34 Building on the Fundamentals Mike Carscaddon, MBA ’08, nails a solid foundation in p. 28 international field operations at Habitat for Humanity. 38 Adventures of an Entrepreneur George Deeb, BBA ’91, seeks big thrills in small firms. 40 Re-Energizer Donna Zobel, MBA ’04, revives the family business and powers up for the new energy economy. 42 Kickstarting a Career Edward Chan-Lizardo, MBA ’95, pumps up nonprofit KickStart in Kenya. -

Local Governments and Mayors As Amici Curiae in Support of the Employees ______Michael N

Nos. 17-1618, 17-1623, 18-107 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________________ GERALD LYNN BOSTOCK, Petitioner, v. CLAYTON COUNTY, GEORGIA, Respondent. __________________ ALTITUDE EXPRESS, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. MELISSA ZARDA, et al., Respondents. __________________ R.G. & G.R. HARRIS FUNERAL HOMES, INC., Petitioners, v. EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION, Respondent, and AIMEE STEPHENS, Respondent- Intervenor. __________________ On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals for the Eleventh, Second, and Sixth Circuits __________________ BRIEF OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS AND MAYORS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE EMPLOYEES __________________ MICHAEL N. FEUER ZACHARY W. CARTER City Attorney Corporation Counsel JAMES P. CLARK RICHARD DEARING KATHLEEN KENEALY DEVIN SLACK BLITHE SMITH BOCK LORENZO DI SILVIO MICHAEL WALSH DANIEL MATZA-BROWN DANIELLE L. GOLDSTEIN NEW YORK CITY Counsel of Record LAW DEPARTMENT OFFICE OF THE LOS 100 Church Street ANGELES CITY ATTORNEY New York, NY 10007 200 N. Main Street, 7th Fl. Los Angeles, CA 90012 Counsel for Amici Curiae (213) 978-8100 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . 1 ARGUMENT . 2 I. Local Experience Shows That Prohibiting All Forms of Sex-Based Discrimination Benefits the Entire Community. 2 A. Non-discrimination laws and policies enhance amici’s operations. 3 B. Communities nationwide have benefitted from such anti-discrimination protections. 5 II. Workplace Discrimination—Including Sex Discrimination Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People—Harms Local Governments. 7 CONCLUSION. 12 APPENDIX List of Amici . App. 1 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES PAGE CASES Adams v. -

The Village of Biscayne Park 600 NE 114Th St., Biscayne Park, FL 33161 Telephone: 305 899 8000 Facsimile: 305 891 7241

The Village of Biscayne Park 600 NE 114th St., Biscayne Park, FL 33161 Telephone: 305 899 8000 Facsimile: 305 891 7241 AGENDA REGULAR COMMISSION MEETING Log Cabin - 640 NE 114th Street Biscayne Park, FL 33161 Tuesday, August 06, 2019 7:00 pm In accordance with the provisions of F.S. Section 286.0105, should any person seek to appeal any decision made by the Commission with respect to any matter considered at this meeting, such person will need to ensure that a verbatim record of the proceedings is made; which record includes the testimony and evidence upon which the appeal is to be based. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, persons needing special accommodation to participate in the proceedings should call Village Hall at (305) 899 8000 no later than four (4) days prior to the proceeding for assistance. DECORUM - All comments must be addressed to the Commission as a body and not to individuals. Any person making impertinent or slanderous remarks, or who becomes boisterous while addressing the Commission, shall be barred from further audience before the Commission by the presiding officer, unless permission to continue or again address the commission is granted by the majority vote of the Commission members present. No clapping, applauding, heckling or verbal outbursts in support or in opposition to a speaker or his/her remarks shall be permitted. No signs or placards shall be allowed in the Commission Chambers. Please mute or turn off your cell phone or pager at the start of the meeting. Failure to do so may result in being barred from the meeting. -

Open Letter to the University of Michigan February 12, 2019 Re

Open Letter to the University of Michigan February 12, 2019 Re: SPG 601.38: “Required Disclosure of Felony Charges and/or Felony Convictions” and Related University of Michigan Policies We, the Carceral State Project at the University of Michigan--along with the undersigned faculty, students, and staff at the University of Michigan, as well as members of the larger community--wish to register our grave concern regarding the University’s recent implementation of a new policy, SPG 601.38.1 This policy requires faculty, staff, student employees, volunteers, and visiting scholars who find themselves convicted of a felony, and even those merely charged but not convicted, to report it to the University. The University of Michigan already requires all prospective undergraduate and graduate students, faculty members, and staff employees to disclose any previous criminal record (both felonies and misdemeanors) during the admissions or employment application process, including, in some cases, information from otherwise sealed juvenile records.2 The University also currently requires prospective employees, including graduate students, to undergo a criminal background check conducted by a private, for-profit company to identify any felony and misdemeanors convictions or pending charges.3 Although the University argues that SPG 601.38 will “better promote safety and security and mitigate potential risk,” this self-disclosure mandate adds a newly punitive element to already invasive and unjust policies that cause far more harm than good.4 Taken together, these policies promote over-criminalization rather than public safety, reinforce the racial and economic inequalities in the criminal justice system and on our campus, and have other devastating collateral consequences.5 The role of the University should be to offer education and employment rather than act as an extension of the carceral state. -

Senate the Senate Met at 9:30 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 18, 2005 No. 66 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, EXECUTIVE SESSION called to order by the Honorable SAM PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, BROWNBACK, a Senator from the State Washington, DC, May 18, 2005. of Kansas. To the Senate: NOMINATION OF PRISCILLA Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, RICHMAN OWEN TO BE UNITED PRAYER of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE FOR appoint the Honorable SAM BROWNBACK, a THE FIFTH CIRCUIT The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of Kansas, to per- fered the following prayer: form the duties of the Chair. Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, I ask Let us pray. TED STEVENS, unanimous consent that the Senate Eternal Spirit, the fountain of light President pro tempore. now proceed to executive session to and wisdom, without Whom nothing is Mr. BROWNBACK thereupon as- consider calendar No. 71, the nomina- holy and nothing prevails, You have sumed the Chair as Acting President tion of Priscilla Owen to be United challenged us to let our lights shine, so pro tempore. States Circuit Judge for the Fifth Cir- that people can see our good works and cuit; provided further that the first glorify Your Name. f hour of debate, from 9:45 to 10:45, be Today, shine the light of Your pres- RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME under the control of the majority lead- ence through our Senators and illu- er or his designee; further that the minate our Nation and world. -

Press and Media.May 2019

Media Clips COVERED CALIFORNIA BOARD CLIPS Mar. 18, 2019 – May 15, 2019 Since the Mar. 14 board meeting, high-visibility media issues included: President Trump deciding he wants a GOP plan to replace the Affordable Care Act, before quickly being convinced to shelve the idea until after the 2020 elections. The administration’s Department of Justice declared its opposition to the ACA, filing in a federal appeals court that the legislation is unconstitutional and should be struck down. Meanwhile in California, Gov. Newsom unveiled his new budget that includes changes for Covered California, while Americans weighed in on the current health care climate. COVERED CALIFORNIA PRESS RELEASES AND REPORTS New Analysis Finds Record Number of Renewals for Leading State-Based Marketplaces, but Lack of Penalty Is Putting Consumers at Risk, May 7 ....................... 4 Open Forum: Trump abolished the health care mandate. California needs to restore it, San Francisco Chronicle, May 15, 2019 .......................................................................... 9 PRINT Articles of Significance Gavin Newsom’s health care budget has more help for Covered California, less for undocumented, Sacramento Bee, May 10, 2019 .......................................................... 10 Twelve State-based Marketplace Leaders Express Serious Concerns about Federal Health Reimbursement Arrangement Rule Changes, NASHP, April 29, 2019 .............. 13 3.6 Million Californians Would Benefit if California Takes Bold Action to Expand Coverage and Improve Affordability -

Federal Appellate Judges' Choices About Gender-Neutral Language

Articles Framing Gender: Federal Appellate Judges' Choices About Gender-Neutral Language By JUDITH D. FISCHER* Introduction LANGUAGE IS CRITICALLY IMPORTANT in the two fields at the center of this Article. Language is the tool of the legal profession,1 and feminists recognize that language has been an instrument of both women's oppression and their liberation.2 This Article considers a question relevant to both fields: Are judges using gender-neutral lan- guage? For lawyers, the answer may inform their choice of wording when they write for judges.3 For feminists, the answer will be one marker of the success of their efforts in language reform. * Judith D. Fischer is an Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Louisville's Louis D. Brandeis School of Law. She appreciates the invaluable contribution to this Article's statistical analysis by Professor Jose M. Fernandez of the University of Louisville's Department of Economics and by attorney and mathematics doctoral candidate Carole Wastog. She thanks the law faculty at Indiana University at Indianapolis for their insightful suggestions at a presentation about this study. She is also grateful to Professors Craig Anthony Arnold, Kathleen Bean, Nancy Levit, Nancy Rapoport, and Joel Schumm for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts. Finally, thanks go to Amy Jay for her excellent research assistance. 1. See, e.g., FRANK E. COOPER, WRITING IN LAW PRAcTICE 1 (1963) ("[L]awyers have but one tool-language."); DAVID MELLINKOFF, THE LANGUAGE OF THE LAw, at vii (1963) ("The law is a profession of words."); Debra R. Cohen, Competent Legal Wrting-A Lauryer's ProfessionalResponsibility, 67 U. -

Visiting Judges

Visiting Judges Marin K. Levy* Despite the fact that Article III judges hold particular seats on particular courts, the federal system rests on judicial interchangeability. Hundreds of judges “visit” other courts each year and collectively help decide thousands of appeals. Anyone from a retired Supreme Court Justice to a judge from the U.S. Court of International Trade to a district judge from out of circuit may come and hear cases on a given court of appeals. Although much has been written about the structure of the federal courts and the nature of Article III judgeships, little attention has been paid to the phenomenon of “sitting by designation”—how it came to be, how it functions today, and what it reveals about the judiciary more broadly. This Article offers an overdue account of visiting judges. It begins by providing an origin story, showing how the current practice stems from two radically different traditions. The first saw judges as fixed geographically, and allowed for visitors only as a stopgap measure when individual judges fell ill or courts fell into arrears with their cases. The second assumed greater fluidity within the courts, requiring Supreme Court Justices to ride circuit—to visit different regions and act as trial and appellate judges—for the first half of the Court’s history. These two traditions together provide the critical context for modern-day visiting. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38ZK55M67 Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. -

Isaac D. Buck the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

THE PRICE OF UNIVERSALITY SUSTAINABLE ACCESS AND THE TWILIGHT OF THE ACA Isaac D. Buck The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) was intended to solve problems that had dogged American health care for generations. It built a comprehensive structure—by providing more Americans with accessible health insurance, revamping and reordering the private insurance market, expanding and reconfiguring Medicaid, and installing rational incentives into America’s health care enterprise. Without question, it was the most important piece of health care legislation since the mid-1960s, and it brought about positive change in millions of Americans’ lives. However, over the last eight years, the ACA has faced persistent political, popular, and policy-based challenges. It remains tenuous as its prominent insurance marketplaces precariously teeter. The law’s imperfections continue to fuel an uninterrupted barrage of legal, administrative, and regulatory attacks, which, piece by piece, weaken its overall effectiveness. Its failure to impact the cost of health care has continued to haunt it, making it unclear whether it will fully collapse or whether a mutated version of itself will lumber into the future. Either may be devastating to the future of American health care. In sum, the ACA did not change the dominant paradigm of America’s health care system because it failed to bring about meaningful cost control. While it may have relieved some of America’s worst tendencies, it further cemented a health care non-system, one whose technocratic tinkering could not tape over cracking foundation. Instead of installing a comprehensive system, the ACA opted to try to protect American patients and beneficiaries from the market’s worst effects without any effective means for cost control. -

Congressional Record—Senate S8340

S8340 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE September 9, 2002 reaching the authorization of the funds Midwestern States—is that just refers CONCLUSION OF MORNING available. Certainly that authorization to farmers. I want to tell you it is BUSINESS is not totally enough to fill all the farmers, but it is also those who raise The PRESIDING OFFICER. Morning needs, but it is an improvement over livestock, cattle, and sheep. People business is closed. the past. who are in that business need to be rec- f This also gives an opportunity for ognized as well, in terms of what we do those counties to create their own fi- here to help the agricultural industry EXECUTIVE SESSION nancial structure, much of which often during the drought. We will be dealing is tourism, which, again, is costly. I with that. We will come back to it. NOMINATION OF KENNETH A. thank the committee for what they I say again I hope we can set some MARRA, OF FLORIDA, TO BE have done with respect to payments in priorities for the relatively limited UNITED STATES DISTRICT lieu of taxes to the counties. I hope we amount of time left of this Congress. I JUDGE FOR THE SOUTHERN DIS- are able to include that. Our allocation hope that we select those items that TRICT OF FLORIDA is larger than the House and we need to are timely, that need to be done. I un- bring that up so we have a satisfactory derstand when we come to the end of a The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under arrangement. session everybody has ideas of things the previous order, the hour of 1 p.m. -

Winter 2014 Book

BBAC Program Guide Winter2014 1 | 6 – 4 | 5 1 | 6 – Andrea Tama, White Peony, detail, acrylic ARTISTIC | DISTINCTIVE | BEAUTIFUL Shop! Tim Cory, Murrinie Bowl, glass the BBAC Gallery Shop Gallery Shop Hours: Monday-Thursday, 9am-6pm Friday & Saturday, 9am-5pm 1/6 – 4/5 2 0 1 4 This Winter at the BBAC... Elementary School Classes Gallery Shop Inside Front Cover Grades 1–5 47-49 What You Need to Know! 03 Preschool/Kindergarten & Family Working for You at the BBAC Ages 4 & Up 50-51 From the President & CEO 04 Family Programs for Ages 2 & Up 51 Board of Directors 05 BBAC Staff 05 Spring Break Youth Camps 2014 Faculty Profile 06 Registration Information 52 BBAC Instructors 07 Registration & Policies Adult Classes & Workshops Registration Information 53 Adult Class Level Descriptions 08 Policies 54 Creative Portal 10 Adult Introductory 2D 11 Support Adult Foundations 2D 11 Membership & Support 55 Business & Digital Arts 12 Donors 56-58 Workshops 13 Tributes & Scholarships 60-61 Book Art 14 Ceramic Arts 14-16 Drawing 16-19 Other Creative Experiences Drawing & Painting 19 Shop & Champagne / Holiday Shop 62 Fiber 19 Meet Me @ the BBAC 63 Jewelry & Metalsmithing 20-23 2nd Sundays @ the Center 63 Jewelry & Polymer Clay 23 Seniors @ the Center 63 Mixed Media 24 Rent the BBAC 64 Painting 25-35 Winter Exhibition Schedule Inside Back Cover Photography 35 Printmaking 36-37 Front Cover Photo Credit: Eric Law/ShootMyArt.com™ Sculpture 37 High School Classes & Workshops Grades 9–12 38-42 ArtBridge/TAB Program 43 Middle School Classes Grades 6–8 44-46 BBAC PROGRAM GUIDE 1 Register online at BBArtCenter.org BBAC—Historical Photo Register online at BBArtCenter.org What You Need to Know… A glance at what’s happening this Winter @ the BBAC Scholarships Art Café Know someone who deserves an art class but The Canopy Cart Café serves lunch during the fall, may not be able to afford the tuition? The BBAC winter and spring semesters, Monday thru Friday. -

Appellate Practice Webinar

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Appellate Practice Webinar September 8, 2021 Richmond, VA ********************************************************************** 1. Agenda ********************************************************************** FOURTH CIRCUIT APPELLATE PRACTICE WEBINAR S EPTEMBER 8, 2021, 9:00 A . M .– 12:00 P . M . Introduction: Circuit Judge James A. Wynn, Jr. 9:00 Insights on Supreme Court and Appellate Practice Chief Judge Roger Gregory leads a conversation with Michael Dreeben, former Deputy Solicitor General in charge of the government’s criminal docket. During his 30-year career with the Office of the Solicitor General, Mr. Dreeben argued over 100 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, becoming known for the brilliance of his intellect, his mastery of the art of oral argument, and his commitment to the ideals of justice. In this session, Mr. Dreeben shares his insights on Supreme Court and appellate practice and on representing the United States before the Supreme Court. Roger L. Gregory, Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Michael R. Dreeben, Co-Chair, White Collar Defense and Corporate Investigations Practice, O’Melveny & Myers LLP Introduction: Circuit Judge James A. Wynn, Jr. 10:00 Effective Advocacy before the Fourth Circuit Circuit Judge Albert Diaz moderates a panel discussion with Circuit Judges Paul Niemeyer and Stephanie Thacker and appellate attorneys Kannon Shanmugam and Jennifer May-Parker. The panel shares the dos and don’ts of briefing and argument, answers questions about Fourth Circuit practice and procedure, and offers strategies for effective representation on appeal. Albert Diaz, Circuit Judge U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Paul V. Niemeyer, Circuit Judge, U.S.