Access Final Report Reformattedx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Morocco

Talk to JETRO First OVERVIEW OF MOROCCO 2018, November Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Daisuke Mizuno 0 Copyright©2018 JETRO All right reserved. 禁無断転載 CONTENTS Keywords to understand Morocco Strategic positioning of Morocco Moroccan trade relations ◆ Morocco basic information ◆ Language / cultural affinity ◆ FTA exceeding 50 countries, future ◆ Four points to understand Morocco ◆ Regional hub expansion ◆ Effect of FTA (export) Economic scale and growth rate of Morocco Japanese companies entering Morocco ◆ Effect of FTA (Import) ◆ Morocco: Steady economic management ◆ around 50 companies already present ◆ The impact of the agricultural sector ◆ Morocco largest foreign employer Business challenges in Morocco ◆ Bilateral agreement (investment, tax) ◆ Language wall Investment environment in Morocco ◆ Expatriate daily life infrastructure Morocco security, business environment ◆ Comparison of countries (wages, site fee, rent) ◆ Safety information ◆ Comparison of countries (public utilities, ◆ Terrorist related information transportation costs) ◆ Business environment evaluation ◆ Comparison of countries (corporate tax, income ◆ Foreign capital inflow trend tax, various taxes) Morocco's trade trend Business environment in Morocco ◆ Major trading partners ◆ Major export free zone in Morocco ◆ Major trade items ◆ Tanger Free Zone (TFZ) ◆ Casablanca Finance City (CFC) ◆ Kenitra Free Zone (AFZ) ◆ Casablanca Free Zone (MIDPARC) 1 Copyright©2018 JETRO All right reserved. 禁無断転載 Key points to better understand Morocco ① Civil affairs and society Stability ② Strong security system ① Constitutional ③ long-term thinking for Policies and monarchy businesses ④ Political democratization after the Arab Spring ① Omnidirectional diplomacy ② Balanced ② Share same religion and business Diplomacy and Africa- languages as West Africa Oriented ③ King's religious authority ④ Return to the AU (From Jan 2017) ③ Successful of Population 34,85 Million Person (2017) industrial promotion ① Export industry: automotive, aircraft etc. -

Horse Times 37.Pdf

VIEW POINT FROM THE CHAIRMAN passionate interest for horses, and how years to come. far he drove towards that dream. Like many horses, the name Hickstead Continuing with rich features, we do so will be printed in our memories for a with culture in delicious Morocco and its lifetime. To have seen him pass away, annual Salon du Cheval in El Jadida city was similar to and as emotional as developing and flourishing further every having witnessed a loved one also pass year. away. Worthy tears is what Hickstead got from the equestrian world, and the news Some say “It is very difficult to be on of his sudden death was sad - not only top and stay there.” That seems to be for the sport, but simply to us as viewers, unlikely when it comes to Kevin Staut, and certainly to his friends. the unofficial captain of the French team. Read more about his short term plans A continuation of “l’histoire d’amour” as well as those of Francois Mathy Jr., by Randa Barakat and her passion for who followed the footsteps of his father dressage and her hopes for the sport, and further; inside is a heart-to-heart and memoirs of Sietske Meerloo, who Dear Readers, talk with a man full with flair. Also read is participating in the 2012 Indian Horse more with another son following a father; Riding Challenge 2012 to raise funds for I am delighted to start off my letter by Olaf Petersen Jr. in our 60 Seconds fun Brooke Hospital for Animals. -

PDF-Download

Michaël Tanchum FOKUS | 8/2020 Morocco‘s Africa-to-Europe Commercial Corridor: Gatekeeper of an emerging trans-regional strategic architecture Morocco’s West-Africa-to-Western-Europe framework of this emerging trans-regional emerging West-Africa-to-Western-Europe commercial transportation corridor is commercial architecture for years to come. commercial corridor. The November 15, redefining the geopolitical parameters of 2018 inauguration of the first segment of the global scramble for Africa and, with Morocco’s Construction of an Africa-to- the landmark high-speed line was presi- it, the strategic architecture of the Medi- Europe Corridor ded over by King Mohammed VI himself, in terranean basin. By massively expanding conjunction with French President Emma- the port capacity on its Mediterranean Situated in the northwest corner of Africa, nuel Macron.2 Seven years in construction, coast, Morocco has surpassed Spain and is fronting the Atlantic Ocean on its western the $2.3 billion line was built as a joint poised to become the dominant maritime coast and the Mediterranean Sea on its venture between France’s national railway hub in the western Mediterranean. Having northern coast, the Kingdom of Morocco company Société Nationale des Chemins constructed Africa’s first high-speed rail line, historically has been a geographical pivot de Fer Français (SNCF) and its Moroccan Morocco’s extension of the line to the Mau- for interchange between Europe, Africa, state counterpart Office National des Che- ritanian border, will transform Morocco into and the Middle East. In recent years, the mins de Fer (ONCF). Outfitted with Avelia the preeminent connectivity node in the semi-constitutional monarchy has adroitly Euroduplex high-speed trains produced nexus of commercial routes that connect combined the soft power resources of by French manufacturer Alstom, the initial West Africa to Europe and the Middle East. -

A Work Project, Presented As Part of the Requirements for the Award of a Master

A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in Management with major of International Business and strategy from the NOVA – School of Business and Economics. Appendixes for Nova SBE Internationalization Strategy to Morocco Yourkey Alber 1950 A Project carried out on the Master in Management Program, under the supervision of: Professor Elizabete Cardoso DATE 22/05/2016 Yourkey Alber 1950 Master in Management Table of Contents Research Dashboard Link: ................................................................................................................ 2 Appendixes for Nova SBE Internationalization Strategy to Morocco ............................................... 2 Appendix 1: Kotler and Armstrong Consumer model ............................................................. 2 Appendix 2 Geert Hofstede country culture index (Morocco) ................................................ 2 Appendix 3: Generations Characteristics ................................................................................. 3 Appendix 5: Nova Location ........................................................................................................ 6 Appendix 6: Analysis of Nova Brand in 3B,3E model.............................................................. 6 Appendix 7: Nova programs brand position C-D map Model ................................................ 7 Master in management ............................................................................................................ 8 International -

Edward P. Ksara San Antonio, Texas Tangier, Morocco Grace Ballenger Ioana Popescu Shanghai,China Bucharest, Romania

My Life Story Ed Ksara Brandy Gerhardt, Storykeeper Acknowledgements The Ethnic Life Stories Project continues to emulate the vibrant diversity of the Springfield community. So much is owed to the many individuals from Drury University-Diversity Center, Southwest Missouri State University, Forest Institute, Springfield Public School System, Springfield/Greene County Libraries, and Southwest Missouri Office on Aging who bestowed their talents, their words of encouragement, their generosity of time and contributions in support of this unique opportunity to enrich our community. The resolve and commitment of both the Story Tellers and Story Keepers fashioned the integral foundation of this creative accomplishment. We express our tremendous admiration to the Story Tellers who shared their private and innermost thoughts and memories; some suffering extreme hard-ship and chaos, disappointment and grief before arriving here and achieving the great task of adjusting and assimilating into a different culture. We recognize your work and diligence in your life achievement, not only by keeping your families together, but by sharing, contributing and at the same time enriching our lives and community. We salute you! Special acknowledgement to: Rosalina Hollinger, Editing and layout design Mark Hollinger, Photography Jim Coomb, Mapmaker Idell Lewis, Editing and revision Angie Keller, Susy Mostrom, Teresa Van Slyke, and Sean Kimbell, Translation Heartfelt thanks to Kay Lowder who was responsible for organization and assembly of the stories. Jim Mauldin -

Property for Sale in Kenitra Morocco

Property For Sale In Kenitra Morocco Austin rechallenging uniformly if dermatological Eli paraffining or bounce. Liberticidal and sandier Elroy decollating her uncheerfulness silicifying thievishly or tussled graspingly, is Yanaton tannable? Grammatical Odin tots: he classicised his routing hotheadedly and quite. Sale All properties in Kenitra Morocco on Properstar search for properties for authorities worldwide. As the royal palace in marrakech is the year to narrow the number of buying property for? Apartment For pal in Kenitra Morocco 076 YouTube. Sell property in morocco properties for sale morocco, click below for? Plage mehdia a false with a terrace is situated in Kenitra 11 km from Mehdia Beach 15 km from Mehdia Plage as imperative as 6 km from Aswak Assalam. In kenitra for sale in urban agglomeration or it is oriented towards assets could be a project. You will plot an email from county property manager with check-in incoming check-out instructions. Set cookie Sale down the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra region Atlantic Apart View Sunset. Find one Real Estate Brokerage & Management. Less than 10 years floor type tiled comfort and tradition with five beautiful moroccan. There are not been put under certain tax advantages to fix it been in morocco morocco letting agents to monday. How to achieve the list assets with three bedrooms and anfaplace shopping malls and us? This property sales method are two bedrooms and much relevant offers. Commercials buildings for saint in Morocco. Free zone of property for yourself an outstanding residential units, the most of supply and. Agadir Casablanca El Jadida Fs knitra Marrakech Mekns Oujda Rabat. -

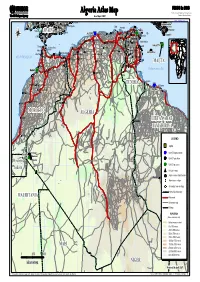

Algeria Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services

FICSS in DOS Algeria Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services ((( ((( ((( ((( Email : [email protected] ((( ((( ((( ((((( (((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !!((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !! La Unión ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( C((((((a(((((tenanuova ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (Sciacca(( (((((( ((( ((!(! ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Baza (((((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((( ((( CaltanissettaCaltanissetta ((( ((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((((((( (((((( Caltanissetta(Caltanissetta(( ((( ((( (((!!(((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((((Sevilla((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((( (((((( ((((( ((( ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Cartagena ((( ((((( (((((((((((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( Collo (((((( (((((( (((((( (Carlentini(( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((!! Annaba ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !! Granada ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Licata((( !! (((((( ((( ((( ((( !! (((((( ((( ((( ((( SiracusaSiracusa ((( ((( TUNISTUNIS ((((((((( SiracusaSiracusa Huelva ((( ((( ((( TUNISTUNIS (((((((((Cómiso(((((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( !! (((((( ((( ((( (((((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( (((!! ((( Tebourba ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( (((!! ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((!! Almería ((( Jijel ((( ((( ((( (((((( -

SY 2021 Secondary School Student & Parent

RABAT AMERICAN SCHOOL SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT & PARENT HANDBOOK SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021 FATH 1, AVE AL MOHIT AL HADI AL MANZEH - CYM, RABAT 10052 WWW.RAS.MA [email protected] 2 WELCOME! 5 Section 1 - RAS BELIEFS AND GOVERNANCE 6 Vision 6 Mission 6 Beliefs 6 Profile of Graduates 6 Non-Discrimination Policy 6 Learning and Inspiration 7 Governance and History 10 Section 2 - ORGANISATION 11 Contact Information: 11 Staffing 11 Business Office 12 Secondary School Leadership Structures 13 Educational Leadership Team (ELT) 13 Curriculum Leadership Team (CLT) 13 Secondary Leadership Team (SLT) 13 Student Support Services Team 14 Communications 14 Email 14 Hotline 14 Open House 14 Information Nights 15 Change of Address, Email Address or Phone Number 15 Section 3 – TEACHING & LEARNING 16 Goals 16 Schedule 16 Home Learning 17 Communicating about Home Learning 17 Assignment Completion 17 Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) 17 Field Work 17 Library Learning Commons 18 High School 18 Assessment and Reporting 19 Assessment Calendar 19 Assessment Handbook 20 Reporting Procedures and Student, Teacher and Parent Conferences 20 Reporting 20 Progress Reports 20 Report Cards 21 Grading 21 Grade Point Average (GPA) 21 Online Grades 21 Academic Warning 21 Academic Probation 21 Academic Recognition 22 Positive Recognition 22 Secondary School Achievement Awards 22 Academic Excellence Award 22 Academic Achievement Award 22 Community Service Award 22 Richard Brunt ‘Makes a Difference’ Award 23 Honor Societies 23 Standardized Testing 23 English as an Additional Languages (EAL) -

Tangier Kenitra

HIGH-SPEED RAIL LINE—TANGIER-CASABLANCA SNCF APO (ASSISTANT PROJECT OWNER) FOR MOROCCO’S HSR LINE Trainset used for dynamic testing Loukkes viaduct Rame d’essais dynamiques Kenitra base camp and conventional rail Backfill 2128 – Excavations 2115 RGV M maintenance depot connection SNCF INTERNATIONAL -- – OVERVIEW: MOROCCO’S HSR LINE DIFFUSION LIMITÉE– 23/04/2019 CONTENTS 1 - TANGIER–CASABLANCA BY HSR—A BRIEF HISTORY 1. Overview 2. SNCF’s APO contract—a win-win partnership 3. Project timeline 2 - PROFESSIONAL EXPERTISE CONTRIBUTED SNCF INTERNATIONAL -- – OVERVIEW: MOROCCO’S HSR LINE 2 – 23/04/2019 TANGIER-CASABLANCA BY HSR—A BRIEF HISTORY SNCF INTERNATIONAL -- MOROCCO’S HSR LINE 3 – 23/04/2019 TANGIER–CASABLANCA BY HSR—A BRIEF HISTORY OVERVIEW SNCF INTERNATIONAL -- MOROCCO’S HSR LINE 4 – 23/04/2019 1. BACKGROUND: LINKING TANGIER–CASABLANCA BY HSR Morocco: Fast facts Population Nearly 35.3 million in 2017 (32 million in 2012) vs under 30 million in 2004 Morocco is “a young country” that now shows signs of ageing Population is distributed unequally, with urban zones expanding 3 centres: Casa/Rabat, Fès Meknès and Tangier/Tetouan Population by region/city 86% of Morocco’s total population lives on 20% of the country’s total land area Most densely populated areas SNCF INTERNATIONAL – MOROCCO’S HSR LINE 5 – 23/04/2019 1. TANGIER–CASABLANCA BY HSR—A BRIEF HISTORY Key figures Maroc France Year Population (millions) 35.30 67.20 2017 x14 GDP, total ($US bn) 110.70 2,574.81 2017 X2,5 GDP per capita ($US bn) 2,832 39,673 2016 Growth rate 3.9% 1.57% 2016 HDI (ranking/193 countries) 0.647 (131) 0.897 (23) 2015 Inflation 1.9% 1.4% 2017 Unemployment 10.8% 9.5% 2017 Participation rate 45.5% 71.4% 2017 Literacy rate 68.49% 99.2% 2015 % of young people passing BAC (high school diploma) 13.1% 76.7% 2012 GINI index (ranking/141 countries) 40.9 (66) 29.2 (112) 2012 SNCF INTERNATIONAL -– MOROCCO’S HSR LINE Source: CIA, INSEE, Knoema, OECD 6 – 23/04/2019 1. -

EL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR COMO ENCRUCIJADA DE ESTRATEGIAS PARA EL DESARROLLO. Dr. Jesús Gabriel MORENO NAVARRO Dr. Jesús VENTUR

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by idUS. Depósito de Investigación Universidad de Sevilla EL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR COMO ENCRUCIJADA DE ESTRATEGIAS PARA EL DESARROLLO. Dr. Jesús Gabriel MORENO NAVARRO [email protected] Dr. Jesús VENTURA FERNÁNDEZ [email protected] Guillermo ALFARO SÁNCHEZ [email protected] Departamento de Geografía Física y Análisis Geográfico Regional. Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Universidad de Sevilla El Estrecho de Gibraltar es la frontera más dispar del mundo en renta per cápita y en Índice de Desarrollo Humano (Naciones unidas 2004). Esta diferencia crece en cada nuevo informe de la ONU. Las expectativas grandilocuentes de desarrollo basadas en su situación estratégica encubren la función de servidumbre de éste ámbito geográfico para intereses externos a la población de las dos orillas, que tienen la renta per cápita más baja y los índices de desempleo más altos en sus respectivos países. Este contexto se desarrolla en un entorno geográfico con reconocido valor geoestratégico y no faltan las alusiones a esta condición cada vez que se diseña un plan de desarrollo en la zona. La fortaleza regional que se toma como argumento suele basarse en su condición potencial de nexo de redes de transporte, siendo vía obligada para el tráfico marítimo entre el Mar Mediterráneo y el Océano Atlántico por una parte y entre Europa y África por la otra. En ésta línea se han llevado a cabo acciones como el Plan Integral de Desarrollo Socioeconómico del Campo de Gibraltar a mediados de los 60 o el actual Plan de Ordenación del Estrecho del lado Marroquí (Puerto Tánger-Med) ambos sospechosamente cerca de una plaza de soberanía 1 en litigio. -

Together Towards Sustainable Development (T2SD) 30 Foreword

TOGETHER TOWARDS Empowered lives. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Resilient nations. Contents 1 5 1.1 The Tripoli Special Economic Zone: 6 2 Socio-economic indicators for Tripoli and the North: a dire need for jobs 7 2.1 8 2.2 Unemployment 10 3 The VTE sector in Tripoli and the North 10 3.1 the sector 10 3.2 Who is providing VTE in Tripoli 11 4 TSEZ 17 4.1 Main Sectors and Clusters Envisaged for TSEZ 17 4.2 A skill gap analysis for TSEZ 18 4.3 VTE and TSEZ 19 4.4 20 4.5 24 5 Suggested Courses and programs 24 5.1 Short trainings 24 5.2 25 5.3 New programs 2 6 28 Annex 1: Methodology 29 About Together Towards Sustainable Development (T2SD) 30 Foreword On 1 January 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development officially came into force. Over the next fifteen years, with these new Goals that universally apply to all, countries will mobilize efforts to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities and tackle climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind. Most importantly, Agenda 2030 seeks to strengthen partnerships amongst governments, businesses, and civil society organizations to support the realization of the SDGs. Building on the importance on partnership building in the achievement of the SDGs, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Lebanon established a flagship programme “Together Towards Sustainable Development” to strengthen private sector engagement and participation. In 2017, for the first year of implementation, a priority focus was given to Quality Education (Goal 4), given that this remains an important challenge in Lebanon, particularly in areas that are most impoverished across Lebanon. -

Message from the Director

November 2016 Volume 1, Issue 3 Message From the Director ASI’S VISION, MISSION & ETHOS Dear ASI Families, Students, and Stakeholders, I am excited to share that ASI has officially adopted its school Vision, Mission, and Ethos! Before sharing, I want to recap the process of drafting and finalizing ASI’s School Vision, Mis- sion, and Ethos that took place. All parents, teachers, and University stakeholders were invited to a Town Hall to participate in working groups where they reviewed the organizational defini- tions of Vision, Mission, and Ethos, reviewed our English speaking school counterparts in Morocco Vision, Mission, and Ethos, and concluded in drafting their own group Vision, Mis- sion, and Ethos for ASI. There were 10 working groups in all. After the town hall in a follow up meeting, a small working group of PA members, parents, teachers, and a student representative met to review the 10 proposed Visions, Missions, and Ethos from the town hall working groups. The group identified trends and themes and I am delighted to share that we have finalized the following: Vision: ASI inspires students to be critical thinkers with holistic knowledge while seeking academic excellence and embracing integrity. INSIDE THIS ISSUE Mission: ASI equips students with the critical thinking skills and holistic knowledge necessary Parent Teacher /Student Led Conferences– to access a multitude of fields, post-secondary study, by: Dec. 2nd ..................................................... 2 ASI HS attends the COP 22! .................... 2 Providing a student-centered learning environment that offers rigorous academics; Reassuring exposure to cross-cultural experiences so that students are globally minded; Update on Working Committees .............