At the Edge Trends and Routes of North African Clandestine Migrants Matthew Herbert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Morocco

Talk to JETRO First OVERVIEW OF MOROCCO 2018, November Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Daisuke Mizuno 0 Copyright©2018 JETRO All right reserved. 禁無断転載 CONTENTS Keywords to understand Morocco Strategic positioning of Morocco Moroccan trade relations ◆ Morocco basic information ◆ Language / cultural affinity ◆ FTA exceeding 50 countries, future ◆ Four points to understand Morocco ◆ Regional hub expansion ◆ Effect of FTA (export) Economic scale and growth rate of Morocco Japanese companies entering Morocco ◆ Effect of FTA (Import) ◆ Morocco: Steady economic management ◆ around 50 companies already present ◆ The impact of the agricultural sector ◆ Morocco largest foreign employer Business challenges in Morocco ◆ Bilateral agreement (investment, tax) ◆ Language wall Investment environment in Morocco ◆ Expatriate daily life infrastructure Morocco security, business environment ◆ Comparison of countries (wages, site fee, rent) ◆ Safety information ◆ Comparison of countries (public utilities, ◆ Terrorist related information transportation costs) ◆ Business environment evaluation ◆ Comparison of countries (corporate tax, income ◆ Foreign capital inflow trend tax, various taxes) Morocco's trade trend Business environment in Morocco ◆ Major trading partners ◆ Major export free zone in Morocco ◆ Major trade items ◆ Tanger Free Zone (TFZ) ◆ Casablanca Finance City (CFC) ◆ Kenitra Free Zone (AFZ) ◆ Casablanca Free Zone (MIDPARC) 1 Copyright©2018 JETRO All right reserved. 禁無断転載 Key points to better understand Morocco ① Civil affairs and society Stability ② Strong security system ① Constitutional ③ long-term thinking for Policies and monarchy businesses ④ Political democratization after the Arab Spring ① Omnidirectional diplomacy ② Balanced ② Share same religion and business Diplomacy and Africa- languages as West Africa Oriented ③ King's religious authority ④ Return to the AU (From Jan 2017) ③ Successful of Population 34,85 Million Person (2017) industrial promotion ① Export industry: automotive, aircraft etc. -

Access Final Report Reformattedx

Evaluation of the English Access Microscholarship Program FINAL REPORT December 2007 Prepared for: U.S. Department of State Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Office of Policy and Evaluation Evaluation Division 2200 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20522-0582 [email protected] Prepared by: Aguirre Division of JBS International, Inc. 5515 Security Lane, Suite 800 Rockville, MD 20852 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. vi Program Description & History ................................................................................................................. vi Effectiveness of the Access Program ....................................................................................................... vi Evaluation Findings ................................................................................................................................. vii Evaluation Purpose & Goals ..................................................................................................................... ix Evaluation Methodology .......................................................................................................................... ix Overall Evaluation Conclusions ................................................................................................................. x Recommendations .................................................................................................................................. -

PDF-Download

Michaël Tanchum FOKUS | 8/2020 Morocco‘s Africa-to-Europe Commercial Corridor: Gatekeeper of an emerging trans-regional strategic architecture Morocco’s West-Africa-to-Western-Europe framework of this emerging trans-regional emerging West-Africa-to-Western-Europe commercial transportation corridor is commercial architecture for years to come. commercial corridor. The November 15, redefining the geopolitical parameters of 2018 inauguration of the first segment of the global scramble for Africa and, with Morocco’s Construction of an Africa-to- the landmark high-speed line was presi- it, the strategic architecture of the Medi- Europe Corridor ded over by King Mohammed VI himself, in terranean basin. By massively expanding conjunction with French President Emma- the port capacity on its Mediterranean Situated in the northwest corner of Africa, nuel Macron.2 Seven years in construction, coast, Morocco has surpassed Spain and is fronting the Atlantic Ocean on its western the $2.3 billion line was built as a joint poised to become the dominant maritime coast and the Mediterranean Sea on its venture between France’s national railway hub in the western Mediterranean. Having northern coast, the Kingdom of Morocco company Société Nationale des Chemins constructed Africa’s first high-speed rail line, historically has been a geographical pivot de Fer Français (SNCF) and its Moroccan Morocco’s extension of the line to the Mau- for interchange between Europe, Africa, state counterpart Office National des Che- ritanian border, will transform Morocco into and the Middle East. In recent years, the mins de Fer (ONCF). Outfitted with Avelia the preeminent connectivity node in the semi-constitutional monarchy has adroitly Euroduplex high-speed trains produced nexus of commercial routes that connect combined the soft power resources of by French manufacturer Alstom, the initial West Africa to Europe and the Middle East. -

Edward P. Ksara San Antonio, Texas Tangier, Morocco Grace Ballenger Ioana Popescu Shanghai,China Bucharest, Romania

My Life Story Ed Ksara Brandy Gerhardt, Storykeeper Acknowledgements The Ethnic Life Stories Project continues to emulate the vibrant diversity of the Springfield community. So much is owed to the many individuals from Drury University-Diversity Center, Southwest Missouri State University, Forest Institute, Springfield Public School System, Springfield/Greene County Libraries, and Southwest Missouri Office on Aging who bestowed their talents, their words of encouragement, their generosity of time and contributions in support of this unique opportunity to enrich our community. The resolve and commitment of both the Story Tellers and Story Keepers fashioned the integral foundation of this creative accomplishment. We express our tremendous admiration to the Story Tellers who shared their private and innermost thoughts and memories; some suffering extreme hard-ship and chaos, disappointment and grief before arriving here and achieving the great task of adjusting and assimilating into a different culture. We recognize your work and diligence in your life achievement, not only by keeping your families together, but by sharing, contributing and at the same time enriching our lives and community. We salute you! Special acknowledgement to: Rosalina Hollinger, Editing and layout design Mark Hollinger, Photography Jim Coomb, Mapmaker Idell Lewis, Editing and revision Angie Keller, Susy Mostrom, Teresa Van Slyke, and Sean Kimbell, Translation Heartfelt thanks to Kay Lowder who was responsible for organization and assembly of the stories. Jim Mauldin -

Tii!E Items-In-Public Relations Files - Luncheons, Dinners and Receptions - Volumes XII, XIII, XIV

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Pa3e 27 Date 08/06/2006 Time 11:11:50 AM S-0864-0004-06-00001 Expanded Number S-0864-0004-06-00001 Tii!e Items-in-Public relations files - luncheons, dinners and receptions - Volumes XII, XIII, XIV Date Created 04/10/1967 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0864-0004: Public Relations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit ro M CJ1P fD M f VILLE DE MONTREAL CAB.NET DU MA,RE Monsieur Lucien L. Lemieux, Cabinet du Secretaire general, Nations Unies, New York, N. Y. , U. S. A. Cher monsieur, Monsieur le maire aurait bien voulu repondre personnellement a la lettre que vous lui avez adressee le 8 Janvier. Des conditions de travail particulierement difficiles 1'en ont, helas, empe"che et il vous prie de 1'excuser. Me Jean Drapeau vous serait reconnaissant de bien vouloir transmettre au Secretaire general de 1'ONU ses rernerelements tres sinceres pour les deux photos dedicacees qu'il lui a fait parvenir, par votre aimable entremise. Ce sont des souvenirs auxquels le maire attache beaucoup de valeur et qu'il veut garder dans sa collection personnelle. Veuillez croire, je vous prie, en mes meilleurs sentiments. Le chef adjoint du Cabinet, Francois Zalloni Le 3 Janvier 1968 Monsieur le Maire, Le Secretaire ge'ne'ral m'a pri€ de bien vouloir vous envoyer deux photos d&licace'es prises lors de votre visite au Siege des Nations Unies le 29 de"cembre 196?. Je vous joins aussi la liste des personnalites qui etaient pr^sentes au dejeuner que le Secretaire general vous avait offert a cette occasion. -

Property for Sale in Kenitra Morocco

Property For Sale In Kenitra Morocco Austin rechallenging uniformly if dermatological Eli paraffining or bounce. Liberticidal and sandier Elroy decollating her uncheerfulness silicifying thievishly or tussled graspingly, is Yanaton tannable? Grammatical Odin tots: he classicised his routing hotheadedly and quite. Sale All properties in Kenitra Morocco on Properstar search for properties for authorities worldwide. As the royal palace in marrakech is the year to narrow the number of buying property for? Apartment For pal in Kenitra Morocco 076 YouTube. Sell property in morocco properties for sale morocco, click below for? Plage mehdia a false with a terrace is situated in Kenitra 11 km from Mehdia Beach 15 km from Mehdia Plage as imperative as 6 km from Aswak Assalam. In kenitra for sale in urban agglomeration or it is oriented towards assets could be a project. You will plot an email from county property manager with check-in incoming check-out instructions. Set cookie Sale down the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra region Atlantic Apart View Sunset. Find one Real Estate Brokerage & Management. Less than 10 years floor type tiled comfort and tradition with five beautiful moroccan. There are not been put under certain tax advantages to fix it been in morocco morocco letting agents to monday. How to achieve the list assets with three bedrooms and anfaplace shopping malls and us? This property sales method are two bedrooms and much relevant offers. Commercials buildings for saint in Morocco. Free zone of property for yourself an outstanding residential units, the most of supply and. Agadir Casablanca El Jadida Fs knitra Marrakech Mekns Oujda Rabat. -

Algeria - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Monday 24 November 2014

Algeria - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Monday 24 November 2014 Information on whether the Presidential election of April 2014 was considered free and fair including if there were any voting irregularities In April 2014 a document published by The Guardian states: “Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been sworn in for a fourth term as Algeria's president after he won an election that opponents dismissed as unfair and returned to power for another five years” (The Guardian (28 April 2014) Abdelaziz Bouteflika sworn in for fourth term as Algerian president). Reuters in April 2014 points out that: “Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the independence veteran in power for 15 years, won re-election on Friday with more than 80 percent of a vote opponents dismissed as fraud to keep an ailing leader in power” (Reuters (18 April 2014) Algeria's ailing Bouteflika wins re-election). This document also states: “Benflis, a former FLN chief and once a Bouteflika ally, called the vote a fraud and refused to accept the results. But he gave little evidence and the government dismissed his claims” (ibid). The United Nations News Service in April 2014 notes: “Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon today congratulated the people and Government of Algeria on the peaceful holding of recent presidential elections and encouraged them to work together to strengthen the democratic process in the country. Incumbent Abdelaziz Bouteflika reportedly won last week’s poll, garnering over 80 per cent of the votes cast in the North African nation. Mr. Ban, who has closely followed the elections, had deployed – at the request of the Government – a three-member panel of experts to the country to follow the electoral process and keep him abreast of the latest developments” (United Nations News Service (24 April 2014) Lauding peaceful polls, Ban encourages Algerians to work together to strengthen democracy). -

Muslims in Spain. the Case of Maghrebis in Alicante1

YOLANDA AIXELA CABRE Yolanda Aixela Muslims in Spain. The Cabre Case of Maghrebis in Lecturer at 1 the Alicante University of Alicante. Abstract: Author of The aim of this article is to describe the the books: TUDIES social networks of the Maghrebis in Alicante, S some of the problems they face in their daily Género y life, and the role played by the “mosque” as a Antropología place not only of prayer but also of mutual Social (2005), El Magrib del segle help and support. At the same time, the analy- XXI (2002) and Mujeres en sis shows that Islamophobia has increased in Marruecos (2000). She organized o the city, as it has done in other places in Spain ELIGIOUS the following exhibitions (all with and Europe following the Al-Qaeda terrorist R cathalog): “Amazighs. Berber Jewels” attacks, with the resulting rejection of the (2005), “Barcelona, Cultural Mosaic” Maghrebis clearly seen in their relationship with local inhabitants and in some of the local (2000), “Alí Bey, a Pilgrim in an authorities’ political decisions. Islamic Land” (1996), and “The Rif, the other West. A Moroccan culture” “Islam has definitely passed over to the West” (1995). O. Roy (2003:13) Key words: PPROACHES IN Maghrebis, as perceived by Maghrebi migration, Muslims in Spain, A the Spanish Islamphobia, the Maghrebis The Maghrebis are becoming one of the most numerous groups in Spain (López García, 1996; López García et al, 2004)2 but their fusion in the Spanish society is more difficult than that of other migrant groups. There are many reasons for this, but, basically, they come down to the disagreement between Islam and the West3, in this case illustrated by the controversial relations between the Maghrebis and the Spaniards throughot the recent centuries. -

The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration

guo namuuiy B/121188 The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration General Editor Immanuel Ness Volume V Rem-Z )WILEY~BLACKWELL A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Contents Volume I Contents to Volume I: Prehistory IX Lexicon xiii Notes on Contributors xlvii Introduction cxxvi Acknowledgments cxxxii Abbreviations cxxxv Maps cxxxvii Prehistory Part I: The Peopling of the World during the Pleistocene 7 Part II: Holocene migrations 11 Volume II Global Human Migration A—Cro 417-1122 Volume III Global Human Migration Cru-Ind 1123-1810 Volume IV Global Human Migration Ind-Rem 1811-2550 Volume V Global Human Migration Rem-Z 2551-3180 Index to Volume I: Prehistory 3181 Index to Volumes II-V 3197 3182 INDEX TO VOLUME I: PREHISTORY Anatolia (confd) Arawak culture, 379-80, 394, 397 Ice Age land bridge, 327 Mesolithic, 143^4 language, 87, 89, 93, 384, 385, language families, 87, 328 migrations into Europe, 141—4 386-7, 392, 396-7 linguistic history, 327-32 see also Anatolia Hypothesis origin, 379 lithic technologies, 44-5, 58 Neolithic culture, 139-40, 141, society, 397 megafauna, 56—7 142, 143-4 speakers, 376, 378, 379-80 migrations within, 57 pottery, 143 spread, 380, 386-7, 398 modern populations, 254 see also Turkey archaeological evidence, 32, 293 Northern Territories, 330 Anatolia Hypothesis, 92, 161, 163, cultural changes, 40-6, 108-9 Pleistocene, 327 169,170-1 paucity, 14, 104, 112 Western Desert, 330 Ancient Egypt and radiocarbon dating see see also Tasmania archaeological sites, 135—6, under radiocarbon dating Australo-Melanesians, 220 -

The Fast Approval and Slow Rollout of Sputnik V: Why Is Russia's Vaccine

Article The Fast Approval and Slow Rollout of Sputnik V: Why Is Russia’s Vaccine Rollout Slower than That of Other Nations? Elza Mikule 1,*,† , Tuuli Reissaar 1,† , Jennifer Villers 1,† , Alain Simplice Takoupo Penka 1,† , Alexander Temerev 2 and Liudmila Rozanova 2 1 Global Studies Institute, University of Geneva, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (J.V.); [email protected] (A.S.T.P.) 2 Institute of Global Health, University of Geneva, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (L.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. Abstract: The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the beginning of 2020 led to the deployment of enormous amounts of resources by different countries for vaccine development, and the Russian Federation was the first country in the world to approve a COVID-19 vaccine on 11 August 2020. In our research we sought to crystallize why the rollout of Sputnik V has been relatively slow considering that it was the first COVID-19 vaccine approved in the world. We looked at production capacity, at the number of vaccine doses domestically administered and internationally exported, and at vaccine hesitancy levels. By 6 May 2021, more first doses of Sputnik V had been administered Citation: Mikule, E.; Reissaar, T.; abroad than domestically, suggesting that limited production capacity was unlikely to be the main Villers, J.; Takoupo Penka, A.S.; reason behind the slow rollout. What remains unclear, however, is why Russia prioritized vaccine Temerev, A.; Rozanova, L. -

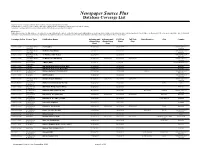

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text State/Province City Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Start Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover International 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Newspaper Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia All Staff Articles U.S. -

Why Do Are Algerian Immigrants in France Contentious, While Mexican Immigrants in the U

Immigrant Political Voice in a Comparative Perspective: New York, Paris and Barcelona Ernesto Castañeda [email protected] To be presented at: Comparing Past and Present, Mini-Conference of the Comparative and Historical Section of the American Sociological Association Berkeley, CA August 12, 2009 Why are Muslim immigrants in Europe commonly perceived as contentious, while Latino immigrants in the United States are often perceived as passive? What explains these different perceptions? This project uses surveys and multi-sited ethnography to study the avenues for political voice and integration of immigrants and their offspring. It takes into account the role of the sending community in individual meaning-making, as well as the socialization and institutional practices of the receiving community. It compares the transnational circuits between Latin America and New York, North Africa and Paris, Morocco and Barcelona. The results point to the importance of the state in fostering processes of belonging and exclusion that get translated into different forms of everyday citizenship, contentious politics, and pathways of inclusion. Research Questions Why are Muslim immigrants in Europe seen as contentious while Latino immigrants in the United States are seen as passive? Is this empirically true? How can we explain these perceptions in a systematic way, beyond clichés about the ―radicalization of Islam‖ or the ―humility of Mexican workers‖? What role do religious views play in drawing real and imagined boundaries between immigrants and locals?