Chesapeake Bay Fisheries: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Route Network

Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Route Network Connecting People and Places Places of Interest Loop Tours Reedville-Colonial Beach Route Belle Isle State Park Located on the Rappahannock River, Dahlgren The Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Reedville and Reedville Fishermen’s Museum Walk this the park includes hiking trails, campsites (with water and Heritage Route network is a segment of the Potomac Heri- fisherman’s village and admire the stately sea captains’ electricity), a modern bath house, a guest house for over- Barnesfield Museum Park tage National Scenic Trail, a developing network homes. Learn about the Chesapeake Bay “deadrise” fish- night rental, a camp store, and kayak, canoe, bicycle and 301 ing boats and sail on an historic skipjack. Enjoy the muse- motor boat rentals. www.virginiastateparks.gov of trails between the broad, gently flowing Po- um galleries. www.rfmuseum.org Caledon Owens tomac River as it empties into the Chesapeake Menokin (c. 1769) Home of Francis Lightfoot Lee, signer State Park DAHLGREN Bay and the Allegheny Highlands in western Vir-Mar Beach A small sandy beach on the Potomac of- of the Declaration of Independence. Visitors center de- 218 fering strolling, relaxing, and birding opportunities. On picting architectural conservation, hiking trails on a 325 Pennsylvania. The “braided” Trail network offers clear days, the Smith Island Lighthouse can be seen, as acre wildlife refuge. www.menokin.org well as the shores of Maryland. www.dgif.virginia.gov/ opportunities for hiking, bicycling, paddling, Oak Crest C Mary Ball Washington Museum & Library Named in M H vbwt/siteasp?trail=1&loop=CNN&site=CNN10 A 206 Winery A horseback riding and cross-country skiing. -

Boats and Harbors Publication 9-06

® -and-har $4.00 ats bor bo s. c w. o w m BOATS & HARBORS w FIRST NOVEMBER ISSUE 2018 VOLUME 61 NO. 18 Covering The East Coast, Gulf Coast, West Coast And All Inland Waterways PH: (931) 484-6100 • FAX: (931) 456-2337 • Email: dmyers@boats-and-harbors Boats and Harbors Can Make Your Business Fat and Sassy Like A Turkey! Serving the Marine Industry Over 40 Years Chris Gonsoulin, Owner • (850) 255-5266 Otherwise........Your Business [email protected] • www.mbbrokerage.net Could End Upside Down Year: 1970 Without A Clucker! Dimensions: 100’ x 30’ x 9.7’ Caterpillar 3516 BOATS & HARBORS® P. O. Drawer 647 Main Engines Crossville, Tennessee 38557-0647 • USA 3,000HP 60KW Generator Sets Twin Disc MG 5600 6:1 ALL ALUMINUM Price: 1.50M REDUCED TO $985K! Year: 1981 Dimensions: 65’ x 24’ Engines: Detroit Diesel 12V-149 Horsepower: 1350HP 40KW Generator Sets Twin Disc Reverse/ Reduction Gears 5.0:1 PRICE: $549K! See Us on the WEB at www.boats-and-harbors.com BOATS & HARBORS PAGE 2 - FIRST NOVEMBER ISSUE 2018 WANT VALUE FOR YOUR ADVERTISING DOLLAR? www.FRANTZMARINE.com 320' x 60' x 28 Built 1995, 222' x 50' clear deck; U.S. flag. Class: Over 38 Years in the Marine Industry ABS +A1 +DP2. 280' L x 60' B x 24' D x 19' loaded draft. Built in 2004, US Flag, 2018 Workboat Edition - OSV’s - Tugs - Crewboats - Pushboats - Derrick Barges Class 1, +AMS, +DPS-2. Sub Ch. L & I. 203' x 50' clear deck. 272' L x 56' B x 18' D x 6' light draft x 15' loaded draft. -

The Ash Breeze

The AshBreezeJournal of the Traditional Small Craft Association WoodenBoat Show Follow-up IN THIS ISSUE Rough Seas at Cape Ann Deltaville Phoenix Marine Wire VOLUME 36, Number 3 • Fall 2015 • $4.00 The Ash Breeze President’s Message: Small Boats in the The Ash Breeze (ISSN 1554-5016) is the quarterly journal of the Traditional Digital Age Small Craft Association, Inc. It is published at Mariner Media, Inc., Marty Loken, President 131 West 21st Street, Buena Vista, VA 24416. Communications concerning As someone obsessed with small ground zero to 1,175 members, with membership or mailings should be boats, I’ve been musing over three more folks joining every day. addressed to: PO Box 350, Mystic, CT heydays of small-craft design, As Josh Colvin, editor of Small 06355. www.tsca.net construction and use: the late 1800s, Craft Advisor, said to me in a recent when so many small work-and- conversation, “We may look back on Volume 36, Number 3 pleasure boats rode their first wave this year as the most exciting time Editor: of popularity; the 1970s, when many ever for small-boat owners. We’ll be Andy Wolfe of us joined the wooden boat revival; glad we were there, back in 2015, and [email protected] and this very minute, today, 2015, part of the excitement.” Advertising Manager: when so many exciting things are Josh may be correct, and I think the Mike Wick unfolding in the world of small boats. main reason for the current heyday— [email protected] This year, you say? How can that be? if we dare call it that—is the ability Well, look around. -

Small Fishing Craf

MECHANIZATION SMALL FISHING CRAF Outboards Inboard Enginc'In Open Craft Inboard Engines in Decked Cra t Servicing and Maintenance Coca ogo Subjects treated in the various sections are: Installation and operation of outboard motors; Inboard engines in open craft; Inboard engines in decked craft; Service and maintenance. Much of the editorial matter is based upon the valuable and authoritative papers presented at a symposium held in Korea and )rganized by the FAO and the Indo- ' acific Council. These papers St.1.07,0,0 MV4,104,4",,,A1M, ; have been edited by Commander John Burgess, and are accom- oanied by much other material of value from various authors. Foreword by Dr. D. B. Finn, C.14.G. Director, Fisheries Division, FAO t has become a tradition for the three sections of FAO's Fisheries Technology BranchBoats, Gear and Processingalternately, in each biennium, to organize a large technical meeting with the participation of both Government institutes and private industry. It all started in 1953 with the Fishing Boat Congress having sessions in Paris and Miami, the proceedings of which were published in " Fishing Boats of the World." A Processing Meeting followed in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in 1956, and a ,ear Congress was organized in Hamburg, Germany, in 1957. A second Fishing Boat Congress was held in Rome in 1959, the proceedings of which were again published in " Fishing Boats of the World :2." Those two fishing boat congresses were, in a way, rather comprehensive, trying to cover the whole field of fishing boat design and also attracting participants from dzfferent backgrounds. This was not a disadvantage, because people having dzfferent experiences were mutually influencing each other and were induced to see further away than their own limited world. -

CT-792 Power Workboat JOHN A. RYDER (Ex-DONNA, CMM 74-114)

CT-792 Power Workboat JOHN A. RYDER (ex-DONNA, CMM 74-114) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 10-29-2003 CT-792 JOHN A. RYDER (ex-DONNA) (clam dredge) Solomons, Maryland JOHN A. RYDER is a 40'6" long V-bottomed, deadrise power workboat, built in 1944 by Bronza M. Parks of Wingate, Maryland. Used as a clam dredge boat and as a research vessel by the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory in Solomons, the boat was built for power and carried a marine gasoline engine. With a beam of 12' and a depth of 2-1/2', the boat is of heavy construction, with a curved stem, flared bows, and a square transom stern with a very slight reverse rake. -

19Th, 20Th and 21St Century Marine Art VOLUME 6 NUMBER 8 - 9 PUBLISHED by J

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 10-11 PUBLISHED by J. RUSSELL JINISHIAN © FALL/WINTER 2006-2007 / $12.00 19th, 20th and 21st Century Marine Art VOLUME 6 NUMBER 8 - 9 PUBLISHED by J. RUSSELL JINISHIAN © FALL/WINTER 2006 / $12.00 Special Double Issue ™ An Insider’s Guide to Marine Art for Collectors and Historians What’s Inside: • Latest News from Today’s Premier Marine Artists, Learn What they’re Working on in their Studios right now • Latest Marine Art Sales & Prices • Marine Art Exhibitions Across the Country Anthony Blake (detail) U.S. Naval Academy Cruise leaving Newport, Rhode Island, 1865 Oil 36” x 48” $55,000 MARION MACEDONIAN AMERICA U.S.S. CONSTITUTION • Upcoming Auctions Wick Ahrens Steve Cryan Glen Hacker Lloyd McCaffery Randy Puckett • Book Reviews Dimetrious Athas R.B. Dance James Harrington Joseph McGurl Keith Reynolds John Atwater William R. Davis Cooper Hart John Mecray Marek Sarba Anthony Blake Don Demers André Harvey Jerry Melton Arthur Shilstone Robert Blazek Louis Dodd Geoff Hunt Stanley Meltzoff Kathy Spalding Christopher Blossom William P. Duffy James Iams Leonard Mizerek Robert Sticker Lou Bonamarte Willem Eerland Antonio Jacobsen William G. Muller John Stobart Willard Bond Carl Evers Michael Keane Rob Napier David Thimgan Peter Bowe William Ewen Loretta Krupinski William Oakley Jr. Tim Thompson Bernd Braatz James Flood Richard Dana Kuchta Russ Kramer Kent Ullberg Al Bross Flick Ford Robert LaGasse Roberto Osti Peter Vincent James Buttersworth Paul Garnett Gerald Levey Yves Parent William Walsh Marc Castelli William Gilkerson Patrick Livingstone Ed Parker Patricia Warfield Scott Chambers James Griffiths Ian Marshall Charles Peterson Robert Weiss Terry Culpan Robert Grimson Victor Mays James Prosek Bert Wright J. -

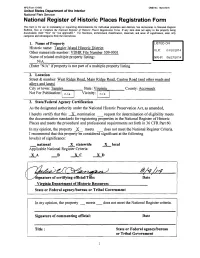

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How lo Complete the National Register of Historic Ploces Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Tangier Island Historic District Other nameslsite number: VDHR File Number 309-0001 Name of related multiple property listing: NIA (Enter "NIA" if property is not part of a multiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: West Ridge Road, Main Ridge Road, Canton Road (and other roads and alleys and lanes) City or town: Tangier State: Virginia County: Accomack Not For Publication: ./, Vicinity: Fl 3. Statemederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: -national -X statewide -X local Applicable National Register Criteria: 8/9R //r~ /- Date Virginia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agencyhureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property -meets -does not meet the National Register criteria. -

United States National Museum

CL v'^ ^K\^ XxxV ^ U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 127 PL. I SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 127 CATALOGUE OF THE WATERCRAFT COLLECTION IN THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM COMPILED AND EDITED BY CARL W. MITMAN Curator, Divisions of Mineral and Mechanical Technology ;?rtyNc:*? tR^;# WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADVERTISEMENT. The .scientific publications of the United States National Museum consist of two series, the Proceedings and the Bulletins. The Proceedings^ the first volume of which was issued in 1878, are intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original and usually brief, papers based on the collections of the National Museum, presenting newly acquired facts in zoology, geology, and anthropology, including descriptions of new forms of animals and revisions of limited groups. One or two volumes are issued annu- ally and distributed to libraries and scientific organizations. A limited number of copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, is dis- tributed to specialists and others interested in the different subjects as soon as printed. The date of publication is recorded in the table of contents of the volume. The Bulletins^ the first of which was issued in 1875, consist of a series of separate publications comprising chiefly monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occa- sionally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, and catalogues of type-specimens, special collections, etc. The majority of the volumes are octavos, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which large plates were regarded as indispensable. Since 1902 a series of octavo volumes containing papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum, and known as the Con- trihutions from the National Herharium.^ has been published as bulletins. -

Recycle Your Oyster Shells! Potomac River Dory Boat with an Authentic Chesapeake Bay Waterman to Learn About This Very Hard Way to Harvest the Bay’S Oysters

Special Activities & Demonstrations Must-See Boats INFORMATION BOOTH & FIRST AID: Located near the Waterfowl Building. Pick up a map and Chesapeake Bay Retriever Marker Demonstrations: Members of the Chesapeake P.E. Pruitt: This 1925 Crisfield-built buyboat is owned by Kevin Flynn, Kevin is happy program, sign up for the Oyster Slurping Contest or stop by if you are in need of First Aid. Bay Retriever Relief and Rescue (CBRR&R) will be on-hand to discuss Maryland’s official to talk about the buyboat’s role as the middle-man, making the rounds to purchase dog and to demonstrate its retrieving ability. Demonstrations on the point near the At oysters from tongers and dredgers aboard skipjacks, bugeyes and other Chesapeake Play on the Bay Building at 11am, Noon, 1pm and 2pm. vessels before transferring them to a wholesaler or oyster processing house. Located at the end of Waterman’s Wharf dock. Cooking Demonstrations: Join local chefs as they prepare exciting oyster dishes. Muriel Eileen: Built in 1926, the Muriel Eileen is a wooden deadrise Chesapeake Bay Maritime Traditions 11:30am Chef Jason Huls-Miller & Owner Jon Mason of Town Dock Food & Spirits buyboat typical of many similar boats of that time. It has a mast and boom forward of Working Boat Shop: Learn about traditional boatbuilding skills at CBMM’s SPAT! Bringing Oysters back to the Chesapeake Bay 12:30pm Chef Daniel Pochron of the Inn at Perry Cabin by Belmond’s Stars the hold with the pilothouse aft of the hold and the hull decked over. It is 58.3’ long working Boat Shop and learn what it takes to keep our floating fleet floating! Maryland and its federal partners are spending about $30 million a year in oyster 1:30pm Chef Patrick Fanning from the High Spot Gastropub with a 18.1’ beam. -

Northern Neck Artifacts, Illustrations and and James Stanton Chase Cut the Ribbon at a Dedication Cer- “Brutal Process,” but Always, He the Rev

Thursday, April 30, 2009 • Kilmarnock, Virginia • Ninety-second Year • Number 29 • Two Sections • 75¢ Boat parade New multi-family to precede residential zone and Blessing proposed $14.6 of the Fleet he community is invited million school budget to participate in the Tannual Blessing of the Fleet Sunday, May 3. set for public hearing This is an ancient tradition LANCASTER—The board School budget celebrated each spring all over of supervisors will conduct The proposed school budget the world, reports Jan Boyd. five public hearings tonight of $14,668,902 is $825,306 The ceremony marks the open- (April 30), including consid- less than the current 2008-09 ing of the fishing season on eration of a new residential budget. the Chesapeake Bay and asks community district ordinance Expected revenues include God’s blessing on the fisher- (R-4) and a fiscal year 2009-10 $3,393,566 from state sources, men and their boats, and for a school budget. down $423,933; $807,491 from fruitful season. The meeting will begin at federal sources, up $36,325; Sponsored by St. Mary’s 7 p.m. in the General District $263,879 from other funds, Episcopal Church in Fleeton courtroom. up $18,031; and $10,203,966 and Omega Protein, the Reed- The proposed R-4 ordinance from county funds, down ville celebration has evolved would allow multi-family $455,729. over the last 38 years to include housing with an emphasis on Estimated expenditures crab potters, pound net fisher- creating workforce housing in include $11,190,858 for men, the menhaden fleet, and off-water residential communi- instruction, down $340,857; pleasure craft from all over the ties. -

United States National Museum, Washington, D

GREAT INTERNATIONAL FISHERIES EXHIBITION. LONDON, 1883. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. I. CATALOGUE OF THE COLLECTION ILLUSTRATING THE FISHING VESSELS AND BOATS, AND THEIR EQUIPMENT; THE ECONOMIC CONDITION OF FISHERMEN; ANGLERS' OUTFITS, ETC. CAPTAIN J. W. COLLINS, Assistant, U. S. Fish Commission. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1 8 S 4 . 645 : — TABLE OF CONTENTS. A. Introduction. Page. Statistics and history of fishing vessels 7 Statistics and history of fishing boats 12 Apparatus accessory to rigging fishing vessels 14 Fishermen and their apparel 19 Food, medicine, and shelter 21 Fishermen's log-books 22 Fishermen's widows and orphans aid societies 22 B.—Fishing craft. VESSELS. Rigged models 1. Fishing steamers 26 2. Fishing ketches 26 3. Fishing schooners 27 Builders' models: 4. Fishing schooners . 37 BOATS. 5. Sloop, cutter, and cat-rigged square-stern boats 45 6. Schooner-rigged square-stern boats 49 7. Square-stern row-boats 50 8. Sharp-stern round-bottom boats 50 9. Flat-bottom boats 54 10. Portable boats 58 11. Sportsmen's boats 61 12. Bark canoes 62 13. Skin boats and canoes 62 14. Dug-outs 63 SKETCHES AND PHOTOGRAPHS OF VESSELS AND BOATS. 15. General views of fishing fleets 65 16. Fishing steamers 66 17. Square-rigged vessels 67 18. Fishing schooners 67 Pinkeys 67 Mackerel-fishing vessels 66 Cod-fishing vessels 70 Fresh-halibut vessels „ 71 Herring catchers 72 Fishing schooners, general 72 [3] 647 — 648 CONTENTS. [4] 19. Sloops 73 20. Cutters 73 21. Quoddy and Block Island boats , 74 22. Seine-boats 74 23; Sharpies... , ... , , 74 24. Dories 75 25. -

Boats and Harbors Publication 9-06

® $4.00 -and-har ats bo bo rs. c w. o w m BOATS & HARBORS w SECOND OCTOBER ISSUE 2018 VOLUME 61 NO. 16 Covering The East Coast, Gulf Coast, West Coast & Inland Waterways “THE” MARINE MARKETPLACE PH: (931) 484-6100 • FAX: (931) 456-2337 • Email: [email protected] HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH MUST SELL! MOTIVATED SELLER370’ Long x 85’ Wide x 55’ Tall ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES! • BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY! ACCOMMODATION BARGE - Perfect For Oil Rig Support, Fishing / Gaming Lodge, Private Island, Floating Hotel, 14,000 sq ft Unused Space Ready For Casino Or More Accommodation Rooms Features: 38 Rooms, Up To 300 People • Pool • Movie Theater • Bar • Full Restaurant, Aquarium, 11,000 lb Helideck, Boat Crane For Lifting 32’ Boats • 70’ Marina • 2 Water Makers • 4 CAT Gens Ready For Immediate Delivery! FULL RESTAURANT Cash Price: $6M !!!! 11,000LB HELIDECK Just Reduced By $1M!!! 727-441-3474 The Three Stages of Advertising Success Boat Load!!! Nibbles No Bites Bringing Buyers and Sellers Together Since 1958 Boats & Harbors Fad You Get A Print & Digital Advertising Line and I’ll Editions Get A Pole... BOATS & HARBORS® P. O. Drawer 647 Crossville, Tennessee 38557-0647 • USA PAGE 2 - SECOND OCTOBER ISSUE 2018 See Us on the WEB at www.boats-and-harbors.com BOATS & HARBORS WANT VALUE FOR YOUR ADVERTISING DOLLAR? WATER COOLED EXHAUST MANIFOLDS For 3-71 , 4-71, & 6-71 Detroit Diesel DD-1-6710 3-71 & 6V71............................................................................$225.00 4-71 & 8V71............................................................................$250.00 6-71 & 12V71.........................................................................$325.00 25’ LANDING CRAFT WORK BOAT 20’, 24’ - IN STOCK 4” NPT EXHAUST END PLATE...................................$40.00 Water Cover Plate (Specify Pipe Size).....................$9.00 BARR MARINE BY EDM 100 Douglas Way, P.O.