“Something Invisible Finding a Form”: Feeling History in Michael Ondaatje’S Coming Through Slaughter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor David Ake, University of Miami Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro Associate Professor Mark Clague © Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik 2016 DEDICATION To Jarvis P. Chuckles, an amalgamation of all those who made this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation was made possible by fellowship support conferred by the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, as well as ample teaching opportunities provided by the Musicology Department and the Residential College. I am also grateful to my department, Rackham, the Institute, and the UM Sweetland Writing Center for supporting my work through various travel, research, and writing grants. This additional support financed much of the archival research for this project, provided for several national and international conference presentations, and allowed me to participate in the 2015 Rackham/Sweetland Writing Center Summer Dissertation Writing Institute. I also remain indebted to all those who helped me reach this point, including my supervisors at the Hatcher Graduate Library, the Music Library, the Children’s Center, and the Music of the United States of America Critical Edition Series. I thank them for their patience, assistance, and support at a critical moment in my graduate career. This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Bruce Boyd Raeburn and his staff at Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive of New Orleans Jazz, and the staff of the Historic New Orleans Collection. -

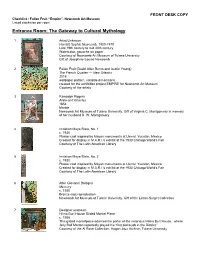

Checklist by Room

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I. -

Performance Shows Complexity of Life in Storyville's Mahogany Hall

Tulane University Performance shows complexity of life in Storyville’s Mahogany Hall October 01, 2018 3:00 PM Miriam Taylor [email protected] Actors Valentine Pierce, left, and Jasmine Davis, are part of the "Postcards from Over the Edge" cast. (Image by CFreedom) Newcomb Art Museum will host the world premiere of Postcards From Over the Edge, a new theatrical work that illustrates the historical struggles related to the sale of sex in Louisiana. Developed collaboratively by five New Orleans–based artists, the play explores New Orleans’ complex relationship with prostitution and is a local project of the National Performance Network. The performance shifts between the Storyville Mahogany Hall era, circa 1890, a time when prostitution was legal, and the actions of the modern-day civil rights movement. Development of Postcards From Over the Edge was initiated by Karel Sloane-Boekbinder, an award-winning multidisciplinary artist and programs assistant in the School of Liberal Arts’ Department of Theatre and Dance. “Because I’m an artist, my first thought was, how do I tell stories that are not being told, how do I share these stories with a larger community, and how do I connect the community together,” said Sloane-Boekbinder. “We think it’s magical that we have the opportunity to perform in a space that has pieces from Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall on display.” Tulane University | New Orleans | 504-865-5210 | [email protected] Tulane University The items once owned by madame Lulu White, proprietor of Storyville’s Mahogany Hall brothel, that are on display as part of the Newcomb Art Museum’s EMPIRE exhibit include salvaged wallpaper, The New Mahogany Hall souvenir booklet, and her desk. -

The Appalling Appeal of the Octoroon: the Shifting Status of Mixed Race Prostitutes in Early Twentieth Century New Orleans

University of North Carolina at Asheville The Appalling Appeal of the Octoroon: The Shifting Status of Mixed Race Prostitutes in Early Twentieth Century New Orleans A Senior Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History by Mesha Maren-Hogan 1 In January of 1917 the working women of Storyville, New Orleans, one of the “wildest and woolliest” red-light districts in the United States, were preparing for Carnival season.1 For some of the district’s most affluent residents, mixed-race brothel owners such as Lulu White, possessor of “the largest collection of diamonds, pearls and other gems” in the South, and “the Countess” Willie V. Piazza, owner of a “two foot ivory, gold and diamond” cigarette holder used exclusively to smoke Russian cigarettes, Carnival season was a time of great business opportunities.2 These madams were busy purchasing cases of champagne and beer, lining up musicians to entertain and ordering new evening gowns and silk stockings.3 Meanwhile, reformers and city officials were hard at work on quite a different project. Led by Commissioner of Public Safety Harold Newman, Progressive reformers set out to clean up the image of New Orleans. One of their main pieces of legislation, City Ordinance 4118, cut right into the heart of the business that allowed White and Piazza to procure their diamonds and gold, namely the selling of the sexual favors of mixed-race “octoroon” women to white men. Ordinance 4118, set to go into effect in March of 1917, would have racially segregated the legal vice district of Storyville, forcing all non-white prostitutes to abandon their richly adorned bordellos and move into the primarily African-American area uptown of Canal Street.4 Ordinance 4118 shook the core of the social traditions and legislation that had brought octoroon women like White and Piazza to such heights of fame and fortune. -

Women Across Texas History, Volume 2

1 Copyright © 2017 by Texas State Historical Association All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions,” at the address below. Texas State Historical Association 3001 Lake Austin Blvd. Suite 3.116 Austin, TX 78703 www.tshaonline.org IMAGE USE DISCLAIMER All copyrighted materials included within the Handbook of Texas Online are in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107 related to Copyright and “Fair Use” for Non-Profit educational institutions, which permits the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), to utilize copyrighted materials to further scholarship, education, and inform the public. The TSHA makes every effort to conform to the principles of fair use and to comply with copyright law. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Dear Texas and Women’s History Enthusiast, As we stand at the 120th Anniversary of the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA) and look back at the more than century of change that has occurred since its founding in 1897, there is a lot to celebrate. The women and men that came together that year had a vision for the study and preservation of Texas history, and while portions of that vision have evolved over time, the foundation remains the same—our shared history is part of who we are. -

5 Shooting at Tuxedo Dance Hall

Tango Belt History - 1 Quotes in Books - 2 Intevriews - 5 Shooting at Tuxedo Dance Hall - 11 More Interviews - 17 The District - 21 The Tango Belt - 26 Photos of Dance Halls - 85 Bios - 98 A Trip to the Past - LaVida, Fern, Alamo - 102 Professors in Storyville - 105 Map of District - 108 List of Clubs - 111 May of Storyville - 114 Anna Duebler (Josie Arlington) - 117 Photos - 134 Tango Dance - 141 1 New Orleans is a port city and as such attracted visitors came from faraway places, especially from South America and the Caribbean. Around 1912 the world was experiencing a Tango dance craze. This craze sweep New Orleans and soon there was a part of the French Quarter that one newspaper reporter, in the part bordering Rampart Street of the Quarter, began calling it “The Tango Belt” with the concentration of halls, cabarets, saloons, restaurants and café centering around the 'unofficial' boundaries of Canal, Rampart, St. Peters and Rampart Streets. Other clubs around the nearby vicinity were also included in this distinction. Articles give other boundaries, but it is in the general area of the upper French quarter and still are considered 'in the District' along with Storyville. There were many places of entertainment within the 'district' (Storyville and the Tango Belt) The Blue Book listed 9 cabarets, four of them-two for whites and two for colored, were not within the boundaries of Storyville: Casino Cabaret (white) 1400 Iberville Street Union Cabaret (white) 135 n. Basin Street Lala's Cabaret (colored) 135 N. Franklin Street New Manhattan Cabaret colored) 1500 Iberville Street In 1917 when the Navy closed Storyville only 5 cabarets were affected, all restricted for the use of whites. -

Dirty Pictures—Not for Sale: Re-Reading Bellocq's Storyville

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship 2013 Dirty Pictures—Not for Sale: Re-reading Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits Mollie S. Le Veque Claremont Graduate University Recommended Citation Le Veque, Mollie S.. (2013). Dirty Pictures—Not for Sale: Re-reading Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/94. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/94 This Open Access Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dirty Pictures—Not for Sale: Re-reading Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits MA Thesis Presented by Mollie Le Veque to Dr Henry Krips and Dr Andrew Long Department of Cultural Studies Claremont Graduate University, Claremont CA 19 April 2013 Le Veque 2 “April 1911 […] I try to pose as I think he would like — shy at first, then bolder. I’m not so foolish that I don’t know this photograph we make will bear the stamp of his name, not mine.”1 “Storyville Diary,” Bellocq’s Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey “Bellocq—whoever he was—interests us […] as an artist: a man who saw more clearly than we do, and who discovered secrets. […] Even if the pictures reproduced here had been widely known a half century ago, they would not have changed the history of photography, for they did not involve new concepts, only an original sensibility.”2 Storyville Portraits, Lee Friedlander The District In 1897—the year that two decriminalized red-light districts within city limits were formed—New Orleans was already internationally known as a place of titillating diversions, and the city possessed a convoluted history: it was founded by the French, ceded to the Spanish, and then brought back to French governance before becoming part of the United States in 1803 under the Louisiana Purchase. -

Racist Stereotypes, Commercial Sex, and Black Women's Identity in New Orleans, 1825-1917

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2014 Animal-Like and Depraved: Racist Stereotypes, Commercial Sex, and Black Women's Identity in New Orleans, 1825-1917 Porsha Dossie University of Central Florida Part of the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Dossie, Porsha, "Animal-Like and Depraved: Racist Stereotypes, Commercial Sex, and Black Women's Identity in New Orleans, 1825-1917" (2014). HIM 1990-2015. 1635. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1635 “ANIMAL-LIKE AND DEPRAVED”: RACIST STEREOTYPES, COMMERCIAL SEX, AND BLACK WOMEN’S IDENTITIY IN NEW ORLEANS, 1825-1917” by PORSHA DOSSIE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts & Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL. Summer Term 2014 Thesis Chair: Connie Lester, PhD 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “I have hated words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.” The Book Thief, Markus Zusack This is, quite possibly, the hardest thing I have ever done in my academic career. I took on the endeavor of writing an undergraduate thesis very lightly, and if not for the following people it would have destroyed me. -

COCKTAILS, KITCHEN, MUSIC and a Sinfully GOOD TIME. APPETIZERS and SHARED PLATES SOUP & SALAD CRAWFISH BOIL OYSTERS

COCKTAILS, KITCHEN, MUSIC AND A Sinfully GOOD TIME. APPETIZERS AND SHARED PLATES CRAWFISH BOIL 25 Cheese Kurtz 11 Crawfish Mkt Price What do you get when real deep-fried Wisconsin cheese curds shack up A pound and a half of quite possibly with the local flavor of the Gulf Coast? The Big Cheesy, of course! the best piece of tail you’ve ever had. Fried Alligator Tail 1525 Crawfish Platter Mkt Price Fresh Louisiana alligator tail with our spicy ranch aioli for dipping. Indulge in a pound and a half of our perfectly seasoned blend of crawfish, 25 Pops’ Bangin’ Shrimp 11 potatoes, sausage and corn. Fried popcorn shrimp glazed in a creamy Thai Chili/honey blend. These babies will keep you moving like the booming sound of Louis Armstrong all night long. Crawfish Sides 925 All the crawfish platter… minus the 25 Homemade Crawfish Pie 13 crawfish! Comes with two potatoes, Creamy risotto-style rice with crawfish and cheese between two flaky layers two corn on the cob and two pieces of puff pastry. of D&D sausage. Mac and Cheese Balls (AKA “Johnny Balls”) 1325 There’s nothing fake about this little number. It’s a classic hookup of OYSTERS cheese and macaroni, blended with our homemade cheesy sauce. Then it’s all beer battered and deep fried. Add bacon crumbles … 2 If there’s one thing Storyville’s scantily clad Olivia the Oyster Dancer knew, 25 Grown-Up Mac & Cheese 10 it was how to make patrons drool. A sexy version of the childhood classic with creamy béchamel Which is why these little numbers and sharp cheddar cheese with crispy panko topping. -

A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazzwomen

A FEMINIST PERSPECTIVE ON NEW ORLEANS JAZZWOMEN Sherrie Tucker Principal Investigator Submitted by Center for Research University of Kansas 2385 Irving Hill Road Lawrence, KS 66045-7563 September 30, 2004 In Partial Fulfillment of #P5705010381 Submitted to New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park National Park Service 419 Rue Decatur New Orleans, LA 70130 This is a study of women in New Orleans jazz, contracted by the National Park Service, completed between 2001 and 2004. Women have participated in numerous ways, and in a variety of complex cultural contexts, throughout the history of jazz in New Orleans. While we do see traces of women’s participation in extant New Orleans jazz histories, we seldom see women presented as central to jazz culture. Therefore, they tend to appear to occupy minor or supporting roles, if they appear at all. This Research Study uses a feminist perspective to increase our knowledge of women and gender in New Orleans jazz history, roughly between 1880 and 1980, with an emphasis on the earlier years. A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazzwomen: A NOJNHP Research Study by Sherrie Tucker, University of Kansas New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park Research Study A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazz Women Sherrie Tucker, University of Kansas September 30, 2004 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................ iii Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 -

Download Full Book

For Business and Pleasure Keire, Mara Laura Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Keire, Mara Laura. For Business and Pleasure: Red-Light Districts and the Regulation of Vice in the United States, 1890–1933. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.467. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 16:48 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For Business & Pleasure This page intentionally left blank studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library For Business & Pleasure Red-Light Districts and the Regulation of Vice in the United States, 1890–1933 mara l. keire The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore ∫ 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Keire, Mara L. (Mara Laura), 1967– For business and pleasure : red-light districts and the regulation of vice in the United States, 1890–1933 / Mara L. Keire. p. cm. — (Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-8018-9413-8 (hbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-8018-9413-1 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Red-light districts—United States—History—20th century. -

Storyville and the Archival Imagination by Nikolas Oscar Sparks

Lost Bodies/Found Objects: Storyville and the Archival Imagination by Nikolas Oscar Sparks Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Maurice O. Wallace, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Sharon P. Holland ___________________________ Frederick Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 ABSTRACT “Lost Bodies/Found Objects: Storyville and the Archival Imagination” by Nikolas Oscar Sparks Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Maurice O. Wallace, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Sharon P. Holland ___________________________ Frederick Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Nikolas Oscar Sparks 2017 Abstract In “Lost Bodies/Found Objects: Storyville and the Archival Imagination,” I engage the numerous collections and scattered ephemera that chronicle the famed New Orleans vice district of Storyville to show the ways in which black life is overwhelmingly criminalized, homogenized, and silenced in narratives of the district. Storyville, the city’s smallest and last vice district, existed from 1897-1917 under the protection of city ordinances. The laws attempted to confine specific vices and individuals within the geographic limits of the district to protect the sanctity of the white family and maintain private property values in the city. As a result, the district strictly managed the lives of women working in the sex trade through policing and residential segregation.